BALTIMORE (AP) — It was almost instinctual for Ray Kelly to jump into action when he heard about a group of high school students clashing with police. He wanted to help protect the kids and de-escalate things, but instead, he watched his neighborhood burn.

Unrest broke out after Freddie Gray died from spinal injuries sustained during transport in a police van in April 2015. The protesters stormed through majority-Black west Baltimore, setting police cars ablaze and looting businesses. They were fighting the generations of oppression experienced by Black Americans, from racist housing policies and crumbling schools to limited job opportunities, rampant gun violence and poor living conditions.

Click to Gallery

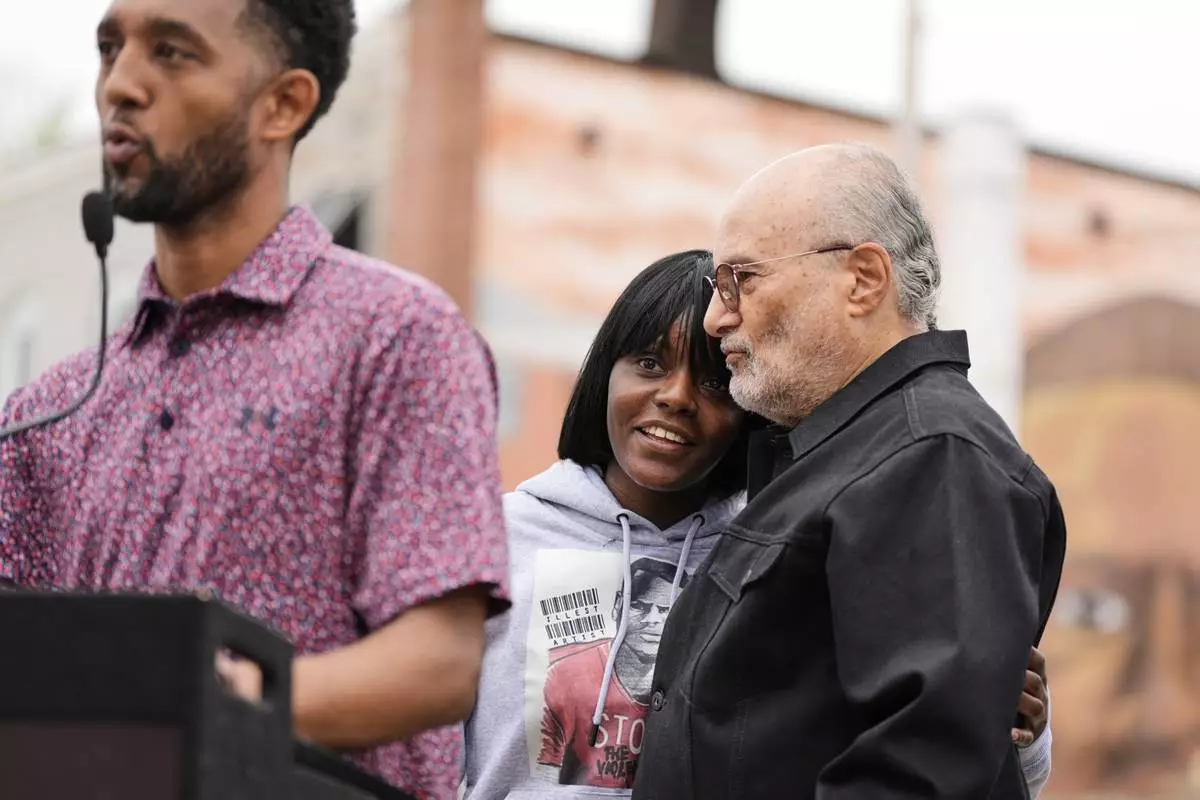

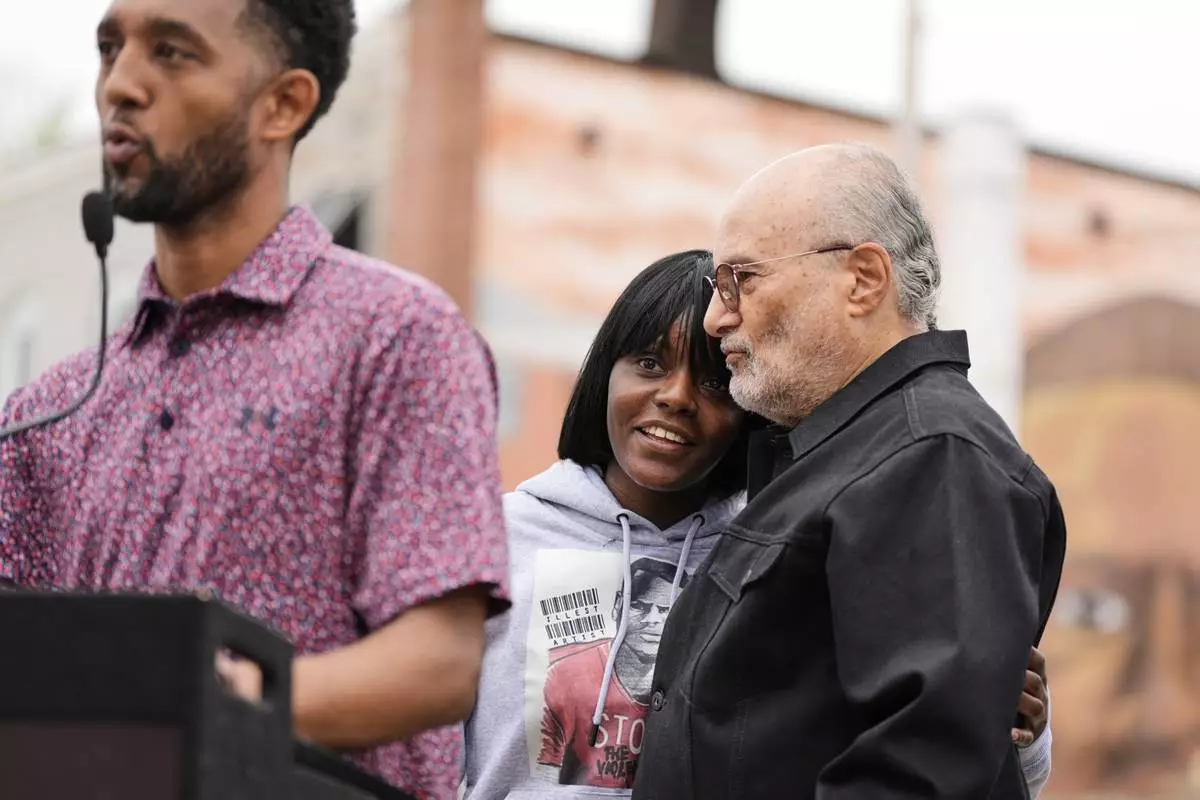

Fredricka Gray, twin sister of Freddie Gray, center, embraces William H. "Billy" Murphy, Jr. as Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott, left, speaks at a memorial event commemorating the ten-year anniversary of the death of Freddie Gray, Saturday, April 19, 2025, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

A street sign identifying the 1700 block of Presbury Street is seen, Monday, April 14, 2025, in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore, where Freddie Gray was arrested before his subsequent death in 2015. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Fredricka Gray, twin sister of Freddie Gray, walks with a wreath to lay during a memorial event commemorating the ten-year anniversary of her brother's death, Saturday, April 19, 2025, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott, left, accompanied by attorney William H. "Billy" Murphy, Jr., speaks at a memorial event commemorating the ten-year anniversary of the death of Freddie Gray, Saturday, April 19, 2025, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

FILE - A mural depicts Freddie Gray, who died from spinal injuries sustained during transport in a Baltimore police van, in Baltimore, May 7, 2015. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky, File)

Abandoned row homes are seen in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore, Monday, April 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Litter lines the street as people walk and congregate on Pennsylvania Avenue near the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore, Monday, April 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

A side entrance of the vacant Lillian S. Jones Recreation Center is boarded shut and a broken window is seen, Monday, April 14, 2025, in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

A sign on the Lillian S. Jones Recreation Center remains despite the center being closed since 20121, as seen in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore, Monday, April 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

A mural dedicated to Freddie Gray is seen Monday, April 14, 2025, in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore, near where he was arrested before his subsequent death in 2015. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Dayvon Love, director of public policy for Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle, speaks during a panel discussion, Thursday, April 10, 2025, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

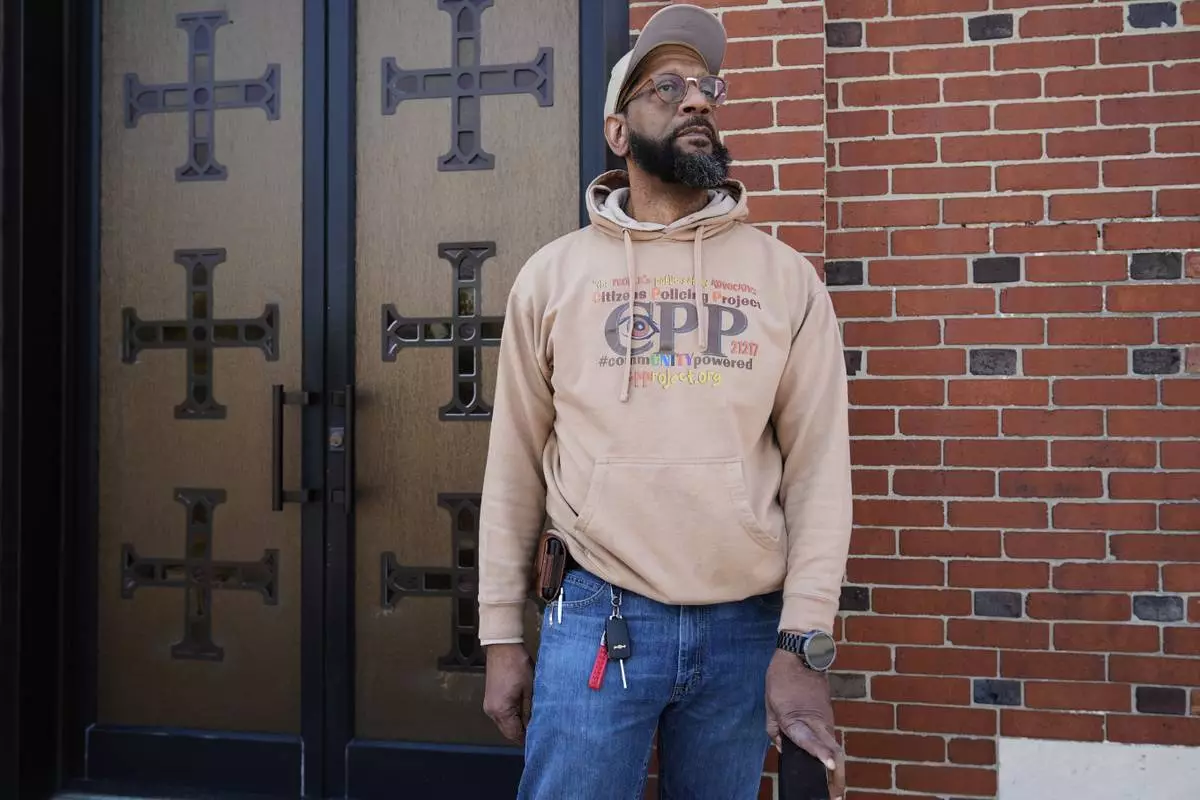

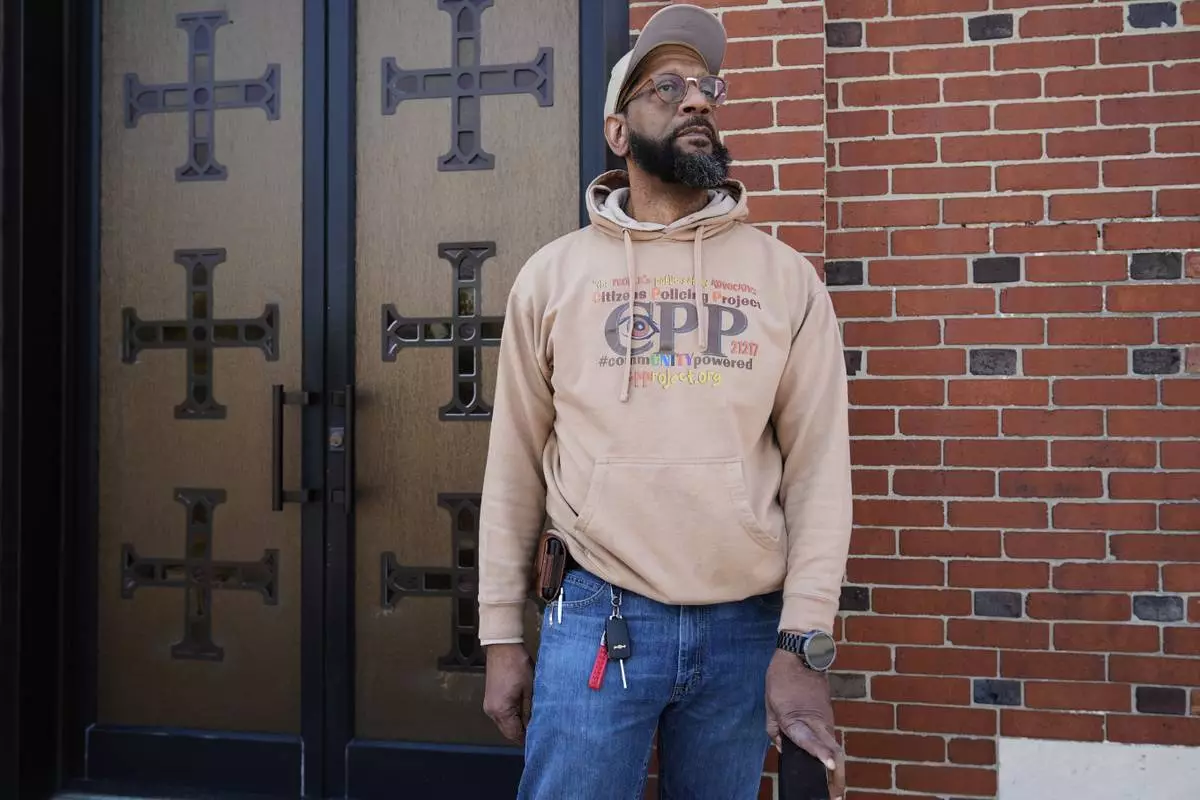

Ray Kelly, executive director of the Citizens Policing Project, listens during a panel discussion, Friday, April 11, 2025, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Fredricka Gray, twin sister of Freddie Gray, center, embraces William H. "Billy" Murphy, Jr. as Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott, left, speaks at a memorial event commemorating the ten-year anniversary of the death of Freddie Gray, Saturday, April 19, 2025, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Ray Kelly, executive director of the Citizens Policing Project, poses for a portrait, Monday, April 14, 2025, in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

FILE - Protesters march through Baltimore the day after charges were announced against the police officers involved in Freddie Gray's death, May 2, 2015. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky, File)

Fredricka Gray, twin sister of Freddie Gray, lays a wreath at a mural during a memorial event commemorating the ten-year anniversary of her brother's death, Saturday, April 19, 2025, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

A mural dedicated to Freddie Gray is seen behind a fence, Monday, April 14, 2025, in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore, near where he was arrested before his subsequent death in 2015. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

A community activist from Gray’s neighborhood, Kelly had focused on police accountability for years. As federal investigators launched a probe into the Baltimore Police Department and local prosecutors charged the officers involved, he doubled down in calling for stronger oversight at a time of growing national outrage over police brutality.

Ten years later, his ongoing efforts illustrate Baltimore’s progress — and lack thereof.

Among the positive changes, Kelly said, there are more mechanisms to address police misconduct and hold officers accountable. Homicides and shootings are trending downward after a prolonged surge that began in the wake of Gray’s death. And while west Baltimore still faces widespread poverty and neglect, he said, at least elected officials are paying more attention.

“People have to hear us out, because there is now this possibility that we can organize and elevate our voices,” Kelly said. “I think Freddie Gray’s death put that in motion.”

But progress is often painfully slow and woefully insufficient. Meanwhile city leaders face new obstacles from the Trump administration’s escalating attacks on civil rights and diversity initiatives.

For Gray’s family, a decade has passed since their private loss played out on national news.

Joined by the mayor and other dignitaries Saturday morning, his twin sister Fredricka laid a wreath of flowers near the site of his arrest, marking the anniversary of when he died in the hospital.

“It’s still justice for Freddie Gray,” she said, repeating what became a rallying cry in 2015. “Ten years now.”

Baltimore has a long history of mistreating its Black residents. In 1910, city leaders enacted the country’s first residential segregation ordinance restricting African American homeowners to certain blocks.

Kelly grew up during the height of the crack cocaine epidemic of the 1980s and the national war on drugs, when police routinely conducted “street sweeps” or mass arrests in west Baltimore. When he started selling drugs to support himself during high school, the police were just another obstacle in an already uphill battle. He later struggled with addiction and served time in prison.

After coming home in the early 2000s, Kelly started working with a neighborhood advocacy group to improve public safety. That put him in a unique position when the U.S. Department of Justice launched its probe of city police: Knowing residents would be wary about cooperating with federal investigators, Kelly helped make introductions and encouraged people to participate.

“It was a gamble,” he said. “It wasn’t really what this community does.”

But the gamble paid off. The investigation uncovered longstanding patterns of excessive force, unlawful arrests and discriminatory policing practices, especially against Black people.

The findings resulted in a 2017 consent decree mandating a series of reforms for the department, which promised to overhaul its policies and training.

Since then, progress is inching along.

The agency celebrated a milestone this week when a federal judge terminated two of the consent decree’s 17 sections after finding full and sustained compliance — including with rules for transporting people in police vans. Gray was handcuffed, shackled and transported without a seatbelt as officers repeatedly ignored his calls for medical attention.

Department leaders say large-scale change is happening, though not overnight. Officers have increased foot patrols, decreased low-level arrests and even undergone training on emotional regulation. They’re less likely to use force when taking people into custody, and they’ve contributed to historic reductions in homicides by partnering with service providers to address the root causes of gun violence.

Police Commissioner Richard Worley said that over the course of his career, he’s watched the culture of policing shift from “warriors to guardians.”

Nonetheless, many Baltimore residents still don’t trust the police to act with compassion and integrity. They don’t believe the department has undergone a significant cultural change.

“It’s going to take years and years to redefine the police department in the eyes of the community,” U.S. District Judge James Bredar said during Thursday’s consent decree hearing. “This work is critical, even if it doesn’t bear fruit immediately.”

Gray, 25, was arrested near his home in west Baltimore’s Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood, a once-thriving community that had fallen into disrepair.

In its heyday, nearby Pennsylvania Avenue was a Black entertainment district with renowned jazz clubs, upscale shops and vibrant nightlife. Its cultural artifacts include the childhood home of Thurgood Marshall, the first African American appointed to the Supreme Court, and a bronze statue of jazz legend Billie Holiday, who also had roots in west Baltimore.

A confluence of factors contributed to its decline, including urban flight and chronic disinvestment. Some businesses left after unrest following the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr.

Open-air drug markets moved in, and over-policing became a common complaint from residents. So when Gray was violently taken into custody after making eye contact with officers and running away, that longstanding frustration boiled over. Officials responded to the 2015 protests by bringing in the Maryland National Guard and imposing a citywide curfew.

Many residents celebrated when prosecutors later announced criminal charges against the six officers involved, but none were convicted.

In the meantime, political leaders visited Sandtown and pledged to invest in housing, youth programs and more. Those big promises have largely failed to materialize.

“It’s still the same damn place with the same damn issues,” Kelly said, gazing down the street outside the former church rectory that houses his advocacy organization, the Citizens Policing Project. “We’ve heard a lot of talk, but this is what we see.”

When the city closed the neighborhood’s recreation center in 2021, Sandtown youth were basically left with nowhere to go, said 17-year-old Ryeheen Watson, whose childhood unfolded in the shadow of Gray’s death.

“It was like, nothing good comes for our community,” he said. “But when you’re starting as an underdog, there’s nowhere to go but up.”

The second Trump administration will likely create even more challenges for communities like Sandtown as the White House slashes federal initiatives aimed at advancing racial equity.

Baltimore attorney Billy Murphy, who represented the Gray family, said that while Black people continue fighting for their collective future, a resurgence of white supremacism is infecting national politics.

“Where are we today? That’s where we are,” Murphy said at a recent event commemorating Gray’s death. “We are heading backwards.”

But at least on the local level, political discourse now includes more progressive Black voices, said Dayvon Love, director of public policy for the grassroots think tank Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle. In his view, Gray’s death was a turning point.

“That has advanced our ability to advocate unapologetically for Black people in ways that before the uprising were shut out,” Love said.

Mayor Brandon Scott says his administration is achieving long-awaited progress by investing in historically neglected neighborhoods, including a $15 million plan to renovate Sandtown’s recreation center and upgrades to Gilmor Homes, the public housing complex where Gray was arrested.

However, Scott said in an interview, “We’re not celebrating here, because the work is not complete.”

For Kelly, discussions of politics and progress often miss the point by failing to acknowledge Gray himself, the young man from west Baltimore who died after a tragic encounter with police a decade ago.

Instead of marking the anniversary of his death, Kelly suggested, perhaps it’s his birthday that should be celebrated: Aug. 16, 1989.

A street sign identifying the 1700 block of Presbury Street is seen, Monday, April 14, 2025, in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore, where Freddie Gray was arrested before his subsequent death in 2015. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Fredricka Gray, twin sister of Freddie Gray, walks with a wreath to lay during a memorial event commemorating the ten-year anniversary of her brother's death, Saturday, April 19, 2025, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott, left, accompanied by attorney William H. "Billy" Murphy, Jr., speaks at a memorial event commemorating the ten-year anniversary of the death of Freddie Gray, Saturday, April 19, 2025, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

FILE - A mural depicts Freddie Gray, who died from spinal injuries sustained during transport in a Baltimore police van, in Baltimore, May 7, 2015. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky, File)

Abandoned row homes are seen in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore, Monday, April 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Litter lines the street as people walk and congregate on Pennsylvania Avenue near the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore, Monday, April 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

A side entrance of the vacant Lillian S. Jones Recreation Center is boarded shut and a broken window is seen, Monday, April 14, 2025, in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

A sign on the Lillian S. Jones Recreation Center remains despite the center being closed since 20121, as seen in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore, Monday, April 14, 2025. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

A mural dedicated to Freddie Gray is seen Monday, April 14, 2025, in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore, near where he was arrested before his subsequent death in 2015. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Dayvon Love, director of public policy for Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle, speaks during a panel discussion, Thursday, April 10, 2025, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Ray Kelly, executive director of the Citizens Policing Project, listens during a panel discussion, Friday, April 11, 2025, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Fredricka Gray, twin sister of Freddie Gray, center, embraces William H. "Billy" Murphy, Jr. as Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott, left, speaks at a memorial event commemorating the ten-year anniversary of the death of Freddie Gray, Saturday, April 19, 2025, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Ray Kelly, executive director of the Citizens Policing Project, poses for a portrait, Monday, April 14, 2025, in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

FILE - Protesters march through Baltimore the day after charges were announced against the police officers involved in Freddie Gray's death, May 2, 2015. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky, File)

Fredricka Gray, twin sister of Freddie Gray, lays a wreath at a mural during a memorial event commemorating the ten-year anniversary of her brother's death, Saturday, April 19, 2025, in Baltimore. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

A mural dedicated to Freddie Gray is seen behind a fence, Monday, April 14, 2025, in the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood in Baltimore, near where he was arrested before his subsequent death in 2015. (AP Photo/Stephanie Scarbrough)

Gregg Popovich stepped down as coach of the San Antonio Spurs on Friday, ending a three-decade run that saw him lead the team to five NBA championships, become the league’s all-time wins leader and earn induction into the Basketball Hall of Fame.

“While my love and passion for the game remain, I’ve decided it’s time to step away as head coach,” Popovich said.

He will remain as team president. Mitch Johnson, a Spurs assistant who filled in for Popovich for the season's final 77 games, becomes the team's head coach.

Popovich, 76, missed all but five games this season after having a stroke at the team’s arena on Nov. 2. He has not spoken publicly since, though had addressed his team at least once and released a statement in late March saying that he hoped to return to coaching.

That won’t be happening.

“I’m forever grateful to the wonderful players, coaches, staff and fans who allowed me to serve them as the Spurs head coach and am excited for the opportunity to continue to support the organization, community and city that are so meaningful to me," Popovich said.

Popovich’s career ends with a record of 1,422-869, which does include the 77 games — 32 wins and 45 losses — that were coached by Johnson this season. He also won 170 playoff games with the Spurs, the most by any coach with any one team and the third-most overall behind only Phil Jackson’s 229 and Pat Riley’s 171.

“The best there ever was,” Spurs great Manu Ginobili said last year of Popovich.

Popovich was a three-time coach of the year, led the U.S. to a gold medal at the Tokyo Olympics and coached six Hall of Famers in San Antonio — Ginobili, David Robinson, Tim Duncan, Tony Parker, Dominique Wilkins and Pau Gasol. He went up against 170 different coaches during his time in the NBA and there have been 303 coaching changes made in the league, including interim moves, during the Popovich era.

“I’ve got a video on my phone that’s, like, priceless,” said Chris Paul, who played for the Spurs this past season — going there, in large part, because of the lure of playing for Popovich. “It was us in Oklahoma City, before shootaround, and Pop is doing ballhandling stuff. All these years I’ve always seen Pop coaching in a suit, but I didn’t know how hard of a worker he was when it comes to training.”

That work ethic, Paul said, carried over into this year after the stroke and Popovich’s commitment to his rehabilitation process.

“I was the first one to get to the arena for games, and I would walk past the training room and Pop would be on the treadmill,” Paul said. “I actually had a chance to be in there while Pop is doing rehab or whatnot. So, to see how hard he works, that’s what I’m glad I got a chance to see. It had nothing to do with basketball. It just showed who he is.”

Popovich, in his role as general manager of the Spurs, made the move to fire coach Bob Hill and promote himself into that job on Dec. 10, 1996. The timing seemed, at best, awkward. The Spurs were 3-15 at that point, having played all 18 of those games without Robinson, who was just about to come back from injury. Popovich took over on the day that Robinson returned to the lineup.

“A change in direction was necessary,” Popovich said that day.

The Spurs hadn’t changed direction again since.

“Coach Pop’s extraordinary impact on our family, San Antonio, the Spurs and the game of basketball is profound,” Spurs managing partner Peter J. Holt said. “His accolades and awards don’t do justice to the impact he has had on so many people. He is truly one-of-one as a person, leader and coach. Our entire family, alongside fans from across the globe, are grateful for his remarkable 29-year run as the head coach of the San Antonio Spurs.”

The fortunes changed — Duncan was picked No. 1 overall in the 1997 draft – but the direction under Popovich always stayed the same. The first championship came in 1999; others followed in 2003, 2005, 2007 and 2014. In his first 22 seasons as head coach, the Spurs had 22 winning records, the first 20 of those seasons winning at least 60% of the time.

His decision to step away now comes with the Spurs having just completed the second year of a rebuild around French star Victor Wembanyama, who arrived touted as the next San Antonio great and has done nothing to suggest he won’t live up to that billing.

Popovich played at the U.S. Air Force Academy, famously wasn’t picked in a bid to make the 1972 U.S. Olympic team — some still say he merited a spot on that team — and wound up becoming a coach who might have been perfectly content to run Pomona-Pitzer, a Division III program in California, for the entirety of his professional life. That school had lost 88 consecutive conference games when he arrived; it didn’t take long for Popovich to deliver a conference championship.

Eventually, the NBA called. In time, Popovich would be paired with Robinson, then the patriarch of a dynasty fueled by Duncan, Parker and Ginobili. And out of that, Popovich put together a career like none other.

“Everyone knows the amazing job he’s done and all the accomplishments,” longtime coach Larry Brown said in 2021. “I wish more people really could know the type of person that he is.”

He was famously grumpy, liked to clash with reporters, rarely offered any details of his basketball or private life other than what was necessary. It was simultaneously real and an act; Popovich has a much softer side as well — he quietly championed causes like the San Antonio Food Bank for years and wasn’t afraid to make his political views known. And those lucky enough to know him find him hilarious.

“He has an amazing sense of humor,” Boston forward Jayson Tatum said while playing for Popovich during the Tokyo Olympics four years ago. “I guess the casual fan sees the person who does those interviews postgame, but that’s not the case of who he is at all. I absolutely love spending time with him.”

A loss in the 2013 NBA Finals crushed Popovich, whose Spurs were in position to close out the Miami Heat in six games, lost Game 6 in overtime after Ray Allen’s 3-pointer with 5.2 seconds remaining in regulation kept the Heat alive, then fell in Game 7. But in the moments after the final horn, as Miami coach Erik Spoelstra embraced his staff, Popovich joined the hug with a wide smile.

Spoelstra, who became head coach of the Heat in 2008, now becomes the league’s longest-tenured in his current position.

“He’s always just been an incredible example of class, dignity,” Spoelstra said of Popovich. “To be able to do that after wins or losses, I just think it’s a great example that you can still have class regardless of how the outcome comes during a game.”

When the Spurs beat the Heat for the title in a finals rematch in 2014, it was Spoelstra who felt the sting of losing. And once again, it was Popovich who sent congratulations on a job well done.

“There is no one out there like Pop,” Golden State coach Steve Kerr said.

Popovich’s was a tenure like few others. Popovich coached the Spurs for 29 seasons, a span nearly unmatched in U.S. major pro sports history. Connie Mack managed the Philadelphia Athletics for 50 years, George Halas coached the Chicago Bears for 40 years and John McGraw managed the New York Giants for 31 years. Those three tenures — all wrapping up well over a half-century ago — are the only ones exceeding the length of Popovich’s coaching run with the Spurs; his 29-year era in San Antonio was matched by the Dallas Cowboys’ Tom Landry and the Green Bay Packers’ Curly Lambeau.

“It means I’m old,” Popovich said last year.

Popovich broke a gender barrier of sorts in the league when he hired Becky Hammon as the league’s first female full-time paid assistant coach. Hammon, now coach of the WNBA’s Las Vegas Aces, would also become the first female head summer league coach in the NBA and first female acting head coach when she replaced Popovich for a game in 2020.

“Basketball is basketball,” South Carolina women’s coach Dawn Staley said when asked about Popovich in 2017. “It doesn’t have a gender. It has a mind. It has an approach. It has a willingness. Given the opportunity, women can excel in this game. As you can see. Becky Hammon is doing a great job. You need more people like Coach Popovich to give them opportunities to learn, to grow, and to embrace it. I don’t think he sees gender. I think he sees someone that has a great basketball mind, that’s tireless. Once you’re given that opportunity, you see great things come out of it.”

Popovich spoke about wine whenever he could and offered his views on politics and current events but rarely offered much insight into coaching decisions or personnel matters. It was almost military-like secrecy, which made sense given that Popovich was a graduate of the U.S. Air Force Academy and was an expert on, among other things, the rise and fall of the Soviet Union.

His love of country led to him taking a small side job during his San Antonio tenure — that being coaching USA Basketball for the 2019 World Cup and the Tokyo Olympics two years later. His World Cup team finished seventh, the worst placing ever for a U.S. team with NBA players. His Olympic team won gold.

“It’s impossible to separate it if you have been in the military,” Popovich said when asked about the parallels of being at the Air Force Academy and coaching the country’s national team. “I’ve had classmates that have fought in wars — I have not — and some of them are no longer with us. You get an appreciation for people who have sacrificed. So, when you have an opportunity to do this for your country, it’s impossible to say no. I love being part of it.”

AP NBA: https://apnews.com/hub/nba

FILE - San Antonio Spurs head coach Gregg Popovich, left, and guard Tony Parker, right, of France, talks during practice, Wednesday, June 12, 2013, in San Antonio, ahead of Game 4 of the NBA Finals against the Miami Heat. (AP Photo/Eric Gay, File)

FILE - Gregg Popovich speaks during his enshrinement at the Basketball Hall of Fame as presenters David Robinson, Tony Parker, Tim Duncan and Manu Ginobili, from left, listen Saturday, Aug. 12, 2023, in Springfield, Mass. (AP Photo/Jessica Hill, File)

FILE - United States players put a gold medal on head coach Gregg Popovich during the men's basketball medal ceremony at the 2020 Summer Olympics, Saturday, Aug. 7, 2021, in Tokyo, Japan. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall, File)

FILE - San Antonio Spurs head coach Gregg Popovich, center, claps during the basketball team's parade and celebration for their fifth NBA Championship, Wednesday, June 18, 2014, in San Antonio. (AP Photo/Michael Thomas, File)