As drivers on U.S. highways cross from one state to another, they often are greeted by a large “Welcome to ....” sign.

But not all drivers are welcome in every state.

In Florida, motorists with special out-of-state driver's licenses issued to those in the U.S. illegally are not welcome to drive. Wyoming enacted a comparable ban this year. And Tennessee's governor said he will sign similar legislation sent to his desk recently.

The message, though not literally printed on metal, is clear: “The sign says, `Welcome to Tennessee, illegal immigrants are not welcome,’” Tennessee House Majority Leader William Lamberth declared during debate.

As President Donald Trump cracks down on illegal immigration, Republican lawmakers in many states are pushing new laws targeting people lacking legal status to live in the U.S. The measures contrast with policies in 19 other states and Washington, D.C., which issue driver's licenses regardless of whether residents can prove their legal presence.

The Justice Department is seeking to strike down one such law in New York, which shields its driver's license data from federal immigration authorities.

States are taking drastically different approaches to licensing drivers even as the federal government attempts to standardize the process.

On May 7, the U.S. will start enforcing a law passed 20 years ago that sets national standards for state driver's licenses to be accepted as proof of identity for adults entering certain federal facilities or traveling on domestic commercial flights. Licenses compliant with the REAL ID Act are marked with a star and require applicants to provide a Social Security number and proof of U.S. citizenship or legal residency.

But states remain free to issue driver's licenses to residents who don't provide documentation for a REAL ID, so long as they meet other state requirements such as passing a vision exam or a driving laws test. In most states that issue licenses to people illegally in the U.S., there is no way currently to know from looking at the license whether the person is unlawfully present or simply chose not to apply for a REAL ID.

But at least some states do make a distinction. Connecticut and Delaware place special markings on driver's licenses issued to immigrants in the U.S. illegally.

In 2023, Florida became the first state to invalidate some other states' licenses. A law signed by Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis made it a misdemeanor punishable by a fine and potential jail time to drive in Florida with a type of license “issued exclusively to undocumented immigrants” or with markings indicating the driver didn't provide proof of lawful presence.

As applied, the law has a limited scope. Only specially marked licenses from Connecticut and Delaware are deemed invalid, according to the website of the Florida Department of Highway Safety and Motor Vehicles.

Connecticut has issued nearly 60,700 “drive-only” licenses to immigrants unable to prove lawful presence. Delaware has not responded to an Associated Press request for such data.

Bidding to avoid Florida's ban, Democratic Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont last year proposed to end the special license designation for immigrants in the U.S. illegally and instead give them the same type of license as others not receiving a REAL ID. But the legislation never came to a vote.

In addition to Wyoming and Tennessee, at least a half-dozen other Republican-led states have considered legislation this year to invalidate certain types of out-of-state driver's licenses issued to immigrants illegally in the U.S., according to an AP analysis using the bill-tracking software Plural. Such legislation passed at least one chamber in Alabama, Montana and New Hampshire and was proposed in North Dakota, Oklahoma and South Carolina.

"We want to discourage illegal immigrants from coming to or staying in Alabama,” said state Sen. Chris Elliott, sponsor of the Alabama bill that awaits House consideration. If someone illegally in the U.S. drives to Alabama, “they should turn around and go somewhere else.”

Frustrated about the legislation, Democratic Alabama state Sen. Linda Coleman-Madison added an amendment requiring highway welcome signs to contain a notice about the prohibited driver's licenses.

“We have people that come here for a lot of events — tourists, vacation, what have you — that could be caught in this. So we need to let people know," she told AP. “I think some of our laws are mean-spirited, and sometimes I think we just have to call it like it is."

The legislation targeting driver's licenses is part of a "trend of states getting involved in federal immigration enforcement issues,” said Kathleen Campbell Walker, an immigration attorney in El Paso, Texas.

It's unclear if the laws carry much substance. Some Florida advocates for immigrants said they are unaware of specific instances where the driver's license ban has been enforced.

But “it is a concern,” said Jeannie Economos, of the Farmworker Association of Florida, “because some people who are undocumented have specifically gone to other states where driver’s licenses are legal to get driver’s licenses to have them here.”

California is among the states where immigrants unlawfully in the U.S. can get driver's licenses. Trump's immigration policies have created “anxiety and fear,” said Robert Perkins, a Los Angeles area attorney who helps immigrants gain legal status.

“Even the ones that might have a California driver’s license, they’re terrified to go anywhere,” Perkins said.

Associated Press writers Susan Haigh and Kimberlee Kruesi contributed to this report.

FILE - Motor vehicle traffic moves along the Interstate 76 highway in Philadelphia, Wednesday, March 31, 2021. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke, File)

The Tennessee State Capitol is seen Feb. 10, 2025, in Nashville, Tenn. (AP Photo/Mark Humphrey)

FILE - Festive banners and bunting hang from and around the Alabama Capitol early Jan. 16, 2011. (AP Photo/Dave Martin, File)

FILE - Heavy snow falls onto the Florida Welcome Center on Jan. 21, 2025 in Pensacola, Fla. (Luis Santana /Tampa Bay Times via AP, File)

VATICAN CITY (AP) — “Conclave” the film may have introduced moviegoers to the spectacular ritual and drama of a modern conclave, but the periodic voting to elect a new pope has been going on for centuries and created a whole genre of historical trivia.

Here are some facts about conclaves past, derived from historical studies including Miles Pattenden's “Electing the Pope in Early Modern Italy, 1450–1700,” and interviews with experts including Elena Cangiano, an archeologist at Viterbo's Palazzo dei Papi (Palace of the Popes).

In the 13th century, it took almost three years — 1,006 days to be exact — to choose Pope Clement IV's successor, making it the longest conclave in the Catholic Church’s history. It's also where the term conclave comes from — "under lock and key," because the cardinals who were meeting in Viterbo, north of Rome, took so long the town's frustrated citizens locked them in the room.

The secret vote that elected Pope Gregory X lasted from November 1268 to September 1271. It was the first example of a papal election by “compromise,” after a long struggle between supporters of two main geopolitical medieval factions — those faithful to the papacy and those supporting the Holy Roman Empire.

Gregory X was elected only after Viterbo residents tore the roof off the building where the prelates were staying and restricted their meals to bread and water to pressure them to come to a conclusion. Hoping to avoid a repeat, Gregory X decreed in 1274 that cardinals would only get “one meal a day” if the conclave stretched beyond three days, and only “bread, water and wine” if it went beyond eight. That restriction has been dropped.

Before 1274, there were times when a pope was elected the same day as the death of his predecessor. After that, however, the church decided to wait at least 10 days before the first vote. Later that was extended to 15 days to give all cardinals time to get to Rome. The quickest conclave observing the 10-day wait rule appears to have been the 1503 election of Pope Julius II, who was elected in just a few hours, according to Vatican historian Ambrogio Piazzoni. In more recent times, Pope Francis was elected in 2013 on the fifth ballot, Benedict XVI won in 2005 on the fourth and Pope Pius XII won on the third in 1939.

The first conclave held under Michelangelo's frescoed ceiling in the Sistine Chapel was in 1492. Since 1878, the world-renowned chapel has become the venue of all conclaves. “Everything is conducive to an awareness of the presence of God, in whose sight each person will one day be judged,” St. John Paul II wrote in his 1996 document regulating the conclave, “Universi Dominici Gregis.” The cardinals sleep a short distance away in the nearby Domus Santa Marta hotel or a nearby residence.

Most conclaves were held in Rome, with some taking place outside the Vatican walls. Four were held in the Pauline Chapel of the papal residence at the Quirinale Palace, while some 30 others were held in St. John Lateran Basilica, Santa Maria Sopra Minerva or other places in Rome. On 15 occasions they took place outside Rome and the Vatican altogether, including in Viterbo, Perugia, Arezzo and Venice in Italy, and Konstanz, Germany, and Lyon, France.

Between 1378-1417, referred to by historians as the Western Schism, there were rival claimants to the title of pope. The schism produced multiple papal contenders, the so-called antipopes, splitting the Catholic Church for nearly 40 years. The most prominent antipopes during the Western Schism were Clement VII, Benedict XIII, Alexander V, and John XXIII. The schism was ultimately resolved by the Council of Constance in 1417, which led to the election of Martin V, a universally accepted pontiff.

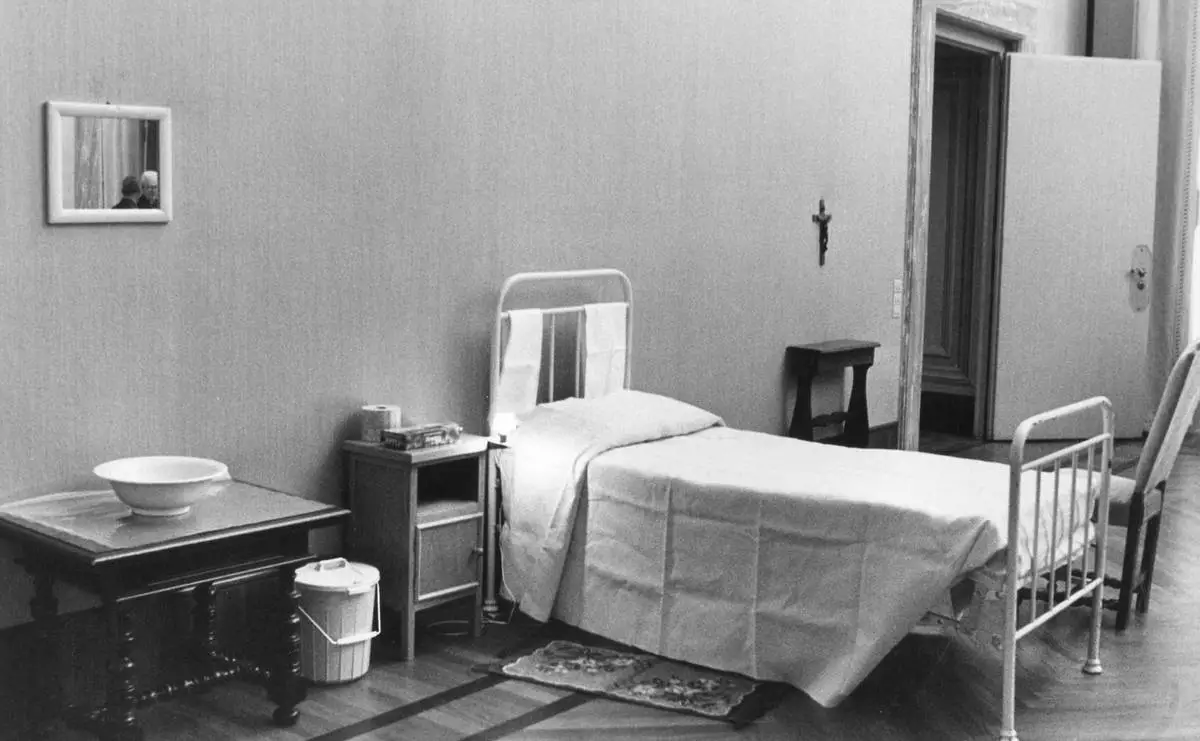

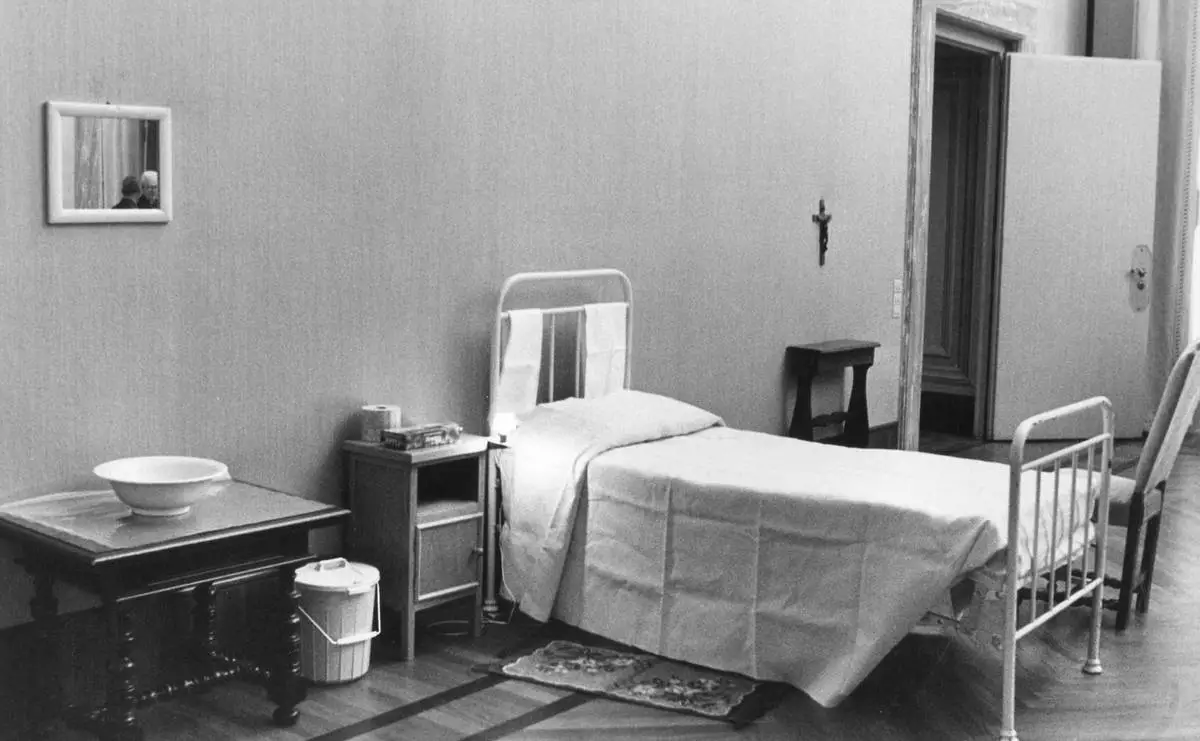

The cloistered nature of the conclave posed another challenge for cardinals: staying healthy. Before the Domus Santa Marta guest house was built in 1996, cardinal electors slept on cots in rooms connected to the Sistine Chapel. Conclaves in the 16th and 17th centuries were described as “disgusting” and “badly smelling,” with concern about disease outbreaks, particularly in summer, according to historian Miles Pattenden. “The cardinals simply had to have a more regular and comfortable way of living because they were old men, many of them with quite advanced disease,” Pattenden wrote. The enclosed space and lack of ventilation further aggravated these issues. Some of the electors left the conclave sick, often seriously.

Initially, papal elections weren’t as secretive, but concerns about political interference soared during the longest conclave in Viterbo. Gregory X decreed that cardinal electors should be locked in seclusion, “cum clave” (with a key), until a new pope was chosen. The purpose was to create a totally secluded environment where the cardinals could focus on their task, guided by God’s will, without any political interference or distractions. Over the centuries, various popes have modified and reinforced the rules surrounding the conclave, emphasizing the importance of secrecy.

Pope John XII was just 18 when he was elected in 955. The oldest popes were Pope Celestine III (elected in 1191) and Celestine V (elected in 1294) who were both nearly 85. Benedict XVI was 78 when he was elected in 2005.

There is no requirement that a pope be a cardinal, but that has been the case for centuries. The last time a pope was elected who wasn’t a cardinal was Urban VI in 1378. He was a monk and archbishop of Bari. While the Italians have had a stranglehold on the papacy over centuries, there have been many exceptions aside from John Paul II (Polish in 1978) and Benedict XVI (German in 2005) and Francis (Argentine in 2013). Alexander VI, elected in 1492, was Spanish; Gregory III, elected in 731, was Syrian; Adrian VI, elected in 1522, was from the Netherlands.

FILE - One of the cells in which a Cardinal will live during the Conclave, at the Vatican, Aug. 23, 1978. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - Cardinals stand in prayer inside the Sistine Chapel after they entered the conclave area for electing the successor of late John Paul I. In the background on the wall Michelangelo's famous fresco "The Last Judgement", in this Oct. 14, 1978 file photo. (AP Photo/Pool, File)

FILE - White smoke is seen billowing out from the chimney of the Sistine Chapel and announcing that a new pope has been elected on Wednesday, March 13, 2013. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, File)

FILE - Italian Cardinal Giacomo Biffi, center, takes an oath at the beginning of the conclave to elect the next pope in the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican, Monday, April 18, 2005. (AP Photo/Osservatore Romano via AP, File)

FILE - Pope Benedict XVI blesses the faithful as he arrives at St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican, Dec. 16, 2010. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino, File)

FILE - Nuns talk in front of Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo Buonarroti's Moses statue, part of a funerary monument he designed for Pope Julius II inside San Pietro in Vincoli Basilica in Rome, July 2, 2013. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, File)

Cardinal Matteo Zuppi, centre, attends a mass on the third of nine days of mourning for late Pope Francis, in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Monday, April 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

FILE - Cardinals walk in procession to the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican, at the beginning of the conclave, April 18, 2005. (Osservatore Romano via AP, File)