BAGHDAD (AP) — An official invitation to new Syrian President Ahmad al-Sharaa to attend the upcoming Arab League summit in Baghdad has triggered sharp political divisions within Iraq.

Al-Sharaa took power after leading a lightning rebel offensive that unseated his predecessor, Bashar Assad, in December. Since then, he has positioned himself as a statesman aiming to unite and rebuild his country after nearly 14 years of civil war, but his past as a Sunni Islamist militant has left many — including Shiite groups in Iraq — wary.

Formerly known by the nom de guerre Abu Mohammed al-Golani, al-Sharaa joined the ranks of al-Qaida insurgents battling U.S. forces in Iraq after the U.S.-led invasion in 2003 and still faces a warrant for his arrest on terrorism charges in Iraq.

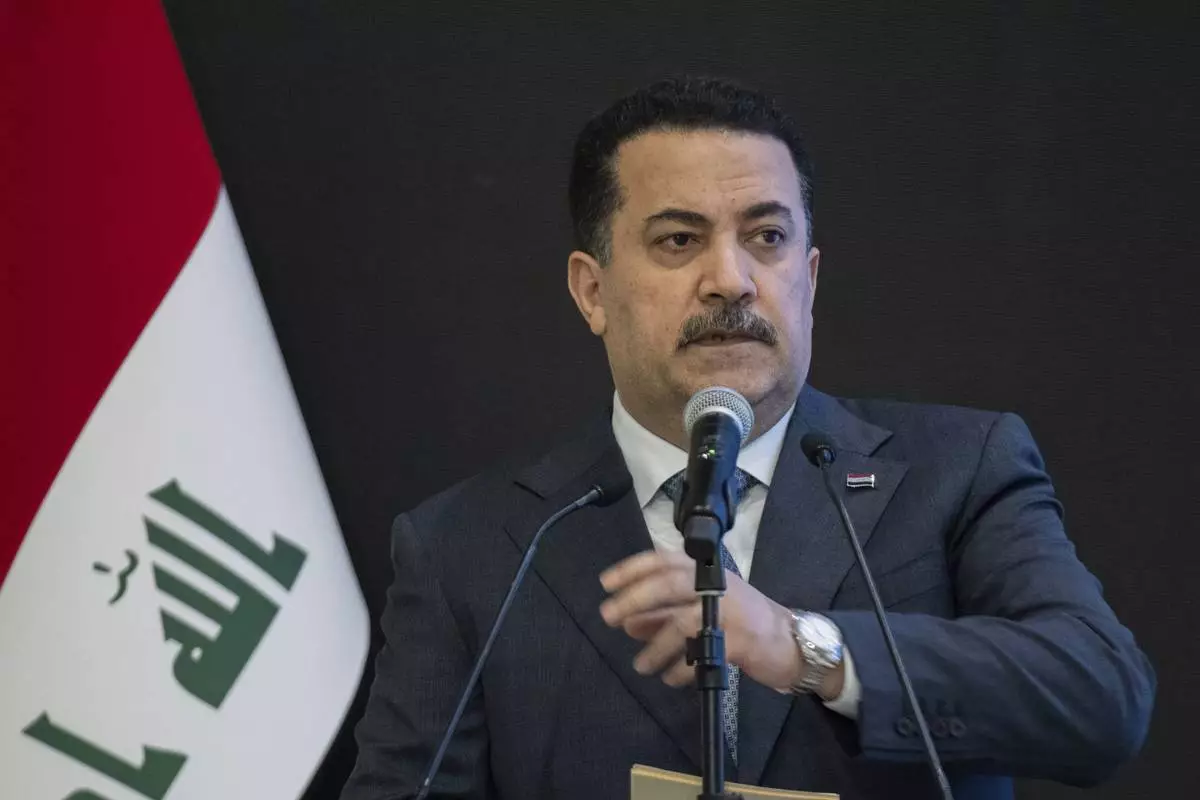

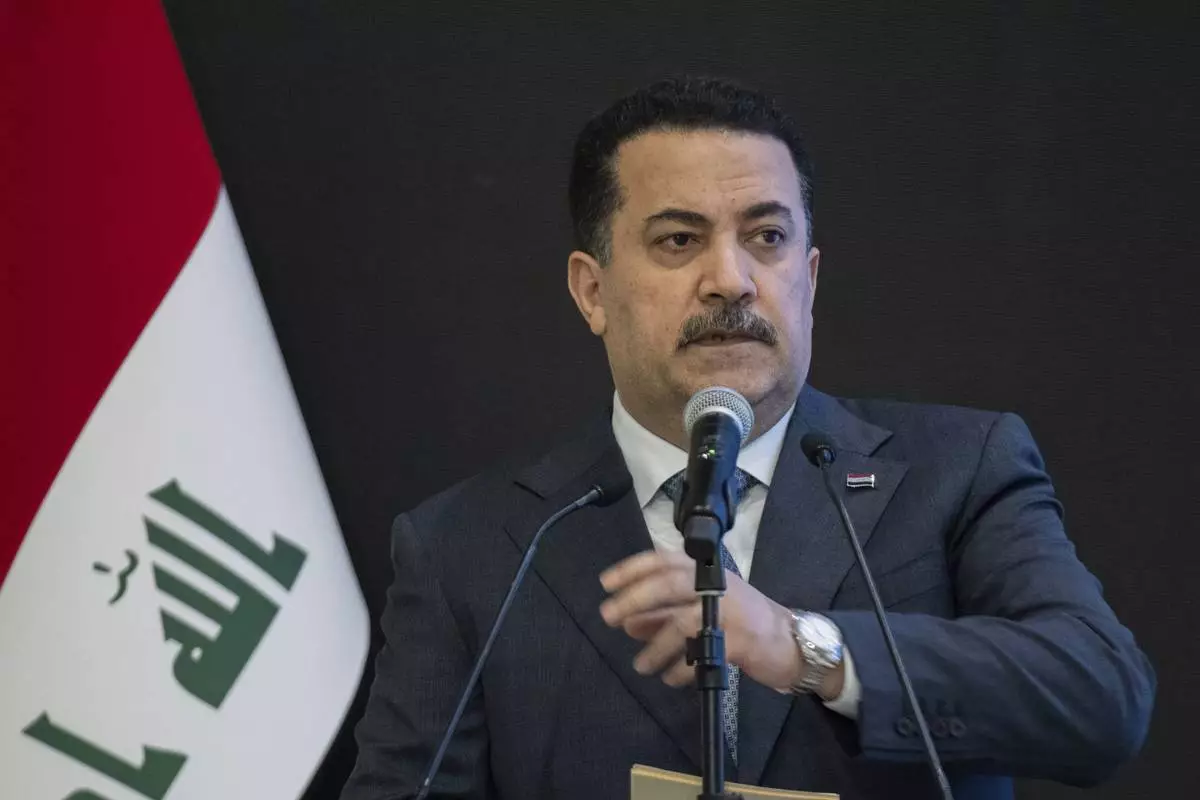

Prime Minister Mohammed Shia Al-Sudani confirmed last week that Iraq had extended a formal invitation to al-Sharaa to attend the May 17 summit, following a previously unannounced meeting between the two in Qatar. Al-Sharaa has not confirmed plans to attend.

Iraq, which has strong ties with both the United States and Iran, has sought to position itself as a regional mediator. It hosted talks between regional rivals Iran and Saudi Arabia before they reached a deal to normalize relations.

Many Iraqi and regional stakeholders see the invitation to al-Sharaa as an opportunity to bolster Baghdad’s image as a hub for regional diplomacy.

However, strong opposition to al-Sharaa’s invitation has emerged from powerful Shiite factions aligned with Iran. Tehran, which backed Assad in Syria’s civil war and used Syria as a conduit to smuggle weapons to the Hezbollah militant group in Lebanon, was widely seen as the biggest loser from Assad’s ouster.

Several Iraqi Shiite militias fought alongside Assad's forces during the civil war that followed his brutal crackdown on pro-democracy protests in 2011, making al-Sharaa a particularly sensitive figure for them.

Mustafa Sand, a member of parliament from the Coordination Framework — a coalition of Iran-allied factions that brought al-Sudani to power in 2022 — said in a video posted on X, formerly Twitter, that the foreign ministry had reached out to Iraq’s Supreme Judicial Council to verify whether an arrest warrant was issued against al-Sharaa and that the council had confirmed the existence of a valid warrant.

A security official who spoke on condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to comment publicly confirmed the existence of the warrant to The Associated Press.

The Islamic Dawa Party, led by former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki — one of the most influential figures in Iraq’s ruling coalition — called on the government in a statement to “ensure that any summit participant has a clean judicial record, both locally and internationally,” adding, “The blood of Iraqis is not cheap, and those who have violated their sanctity or committed documented crimes against them should not be welcomed in Baghdad.”

A spokesperson for the powerful militia Kataib Hezbollah, Abu Ali Al-Askari, said in a statement, “Arab summits have been held without President Assad, Iraq, or Libya. They certainly won’t stop because the criminal Abu Mohammad al-Golani ... isn’t attending.”

On the other side, Sunni political factions have rallied to defend al-Sharaa’s inclusion in the summit. Former MP Dhafir Al-Ani, a prominent Sunni figure, said he supports Baghdad’s attempts to build ties with the new Syrian authorities.

“Preventing his presence would be a stab in the heart of the Iraqi government and a sign that violence still dictates the country’s fate,” he said.

The Iraqi government has not responded publicly to the backlash.

A warrant would not necessarily block al-Sharaa from joining the summit. Other countries have chosen to waive similar measures. In December after Assad’s fall, the United States said it had decided not to pursue a $10 million reward it had previously offered for al-Sharaa’s capture, although Washington also has not yet officially recognized the new Syrian government.

However, observers said the controversy highlights deep divisions within Iraq’s political system and underscores the challenges facing national reconciliation efforts.

“Some see welcoming al-Sharaa as an insult to the memory of Iraq’s victims, while Sunni factions view his participation as a political victory,” said political analyst Munaf Al-Musawi, head of the Baghdad Center for Strategic Studies. “This could risk fueling sectarian tensions.”

FILE - Syria's interim President Ahmad al-Sharaa, looks on during a joint press conference with Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan at the presidential palace in Ankara, Turkey, Feb. 4, 2025. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco, File)

FILE - Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani speaks during Iraq's banking sector reform conference in Babylon Hotel, Baghdad, Iraq, on April 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Hadi Mizban, File)

VATICAN CITY (AP) — “Conclave,” the movie, may have introduced movie-goers to the spectacular ritual and drama of a modern conclave, but the periodic voting to elect a new pope has been going on for centuries and created a whole genre of historical trivia.

Here are some fun facts about conclaves past, derived from historical studies including Miles Pattenden's “Electing the Pope in Early Modern Italy, 1450–1700” and interviews with experts including Elena Cangiano, an archeologist at Viterbo's Palazzo dei Papi (Palace of the Popes).

In the 13th century, it took almost three years — 1,006 days to be exact — to choose Pope Clement IV's successor, making it the longest conclave in the Catholic Church’s history. It's also where the term conclave comes from — "under lock and key," because the cardinals who were meeting in Viterbo, north of Rome, took so long the town's frustrated citizens locked them in the room.

The secret vote that elected Pope Gregory X lasted from November 1268 to September 1271. It was the first example of a papal election by “compromise,” after a long struggle between supporters of two main geopolitical medieval factions — those faithful to the papacy and those supporting the Holy Roman Empire.

Gregory X was elected only after Viterbo residents tore the roof off the building where the prelates were staying and restricted their meals to bread and water to pressure them to come to a conclusion. Hoping to avoid a repeat, Gregory X decreed in 1274 that cardinals would only get “one meal a day” if the conclave stretched beyond three days, and only “bread, water and wine” if it went beyond eight. That restriction has been dropped.

Before 1274, there were times when a pope was elected the same day as the death of his predecessor. After that, however, the church decided to wait at least 10 days before the first vote. Later that was extended to 15 days to give all cardinals time to get to Rome. The quickest conclave observing the 10-day wait rule appears to have been the 1503 election of Pope Julius II, who was elected in just a few hours, according to Vatican historian Ambrogio Piazzoni. In more recent times, Pope Francis was elected in 2013 on the fifth ballot, Benedict XVI won in 2005 on the fourth and Pope Pius XII won on the third in 1939.

The first conclave held under Michelangelo's frescoed ceiling in the Sistine Chapel was in 1492. Since 1878, the world-renowned chapel has become the venue of all conclaves. “Everything is conducive to an awareness of the presence of God, in whose sight each person will one day be judged,” St. John Paul II wrote in his 1996 document regulating the conclave, “Universi Dominici Gregis.” The cardinals sleep a short distance away in the nearby Domus Santa Marta hotel or a nearby residence.

Most conclaves were held in Rome, with some taking place outside the Vatican walls. Four were held in the Pauline Chapel of the papal residence at the Quirinale Palace, while some 30 others were held in St. John Lateran Basilica, Santa Maria Sopra Minerva or other places in Rome. On 15 occasions they took place outside Rome and the Vatican altogether, including in Viterbo, Perugia, Arezzo and Venice in Italy, and Konstanz, Germany, and Lyon, France.

Between 1378-1417, referred to by historians as the Western Schism, there were rival claimants to the title of pope. The schism produced multiple papal contenders, the so-called antipopes, splitting the Catholic Church for nearly 40 years. The most prominent antipopes during the Western Schism were Clement VII, Benedict XIII, Alexander V, and John XXIII. The schism was ultimately resolved by the Council of Constance in 1417, which led to the election of Martin V, a universally accepted pontiff.

The cloistered nature of the conclave posed another challenge for cardinals: staying healthy. Before the Domus Santa Marta guest house was built in 1996, cardinal electors slept on cots in rooms connected to the Sistine Chapel. Conclaves in the 16th and 17th centuries were described as “disgusting” and “badly smelling,” with concern about disease outbreaks, particularly in summer, according to historian Miles Pattenden. “The cardinals simply had to have a more regular and comfortable way of living because they were old men, many of them with quite advanced disease,” Pattenden wrote. The enclosed space and lack of ventilation further aggravated these issues. Some of the electors left the conclave sick, often seriously.

Initially, papal elections weren’t as secretive, but concerns about political interference soared during the longest conclave in Viterbo. Gregory X decreed that cardinal electors should be locked in seclusion, “cum clave” (with a key), until a new pope was chosen. The purpose was to create a totally secluded environment where the cardinals could focus on their task, guided by God’s will, without any political interference or distractions. Over the centuries, various popes have modified and reinforced the rules surrounding the conclave, emphasizing the importance of secrecy.

Pope John XII was just 18 when he was elected in 955. The oldest popes were Pope Celestine III (elected in 1191) and Celestine V (elected in 1294) who were both nearly 85. Benedict XVI was 78 when he was elected in 2005.

There is no requirement that a pope be a cardinal, but that has been the case for centuries. The last time a pope was elected who wasn’t a cardinal was Urban VI in 1378. He was a monk and archbishop of Bari. While the Italians have had a stranglehold on the papacy over centuries, there have been many exceptions aside from John Paul II (Polish in 1978) and Benedict XVI (German in 2005) and Francis (Argentine in 2013). Alexander VI, elected in 1492, was Spanish; Gregory III, elected in 731, was Syrian; Adrian VI, elected in 1522, was from the Netherlands.

FILE - White smoke is seen billowing out from the chimney of the Sistine Chapel and announcing that a new pope has been elected on Wednesday, March 13, 2013. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, File)

FILE - Italian Cardinal Giacomo Biffi, center, takes an oath at the beginning of the conclave to elect the next pope in the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican, Monday, April 18, 2005. (AP Photo/Osservatore Romano via AP, File)

FILE - Pope Benedict XVI blesses the faithful as he arrives at St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican, Dec. 16, 2010. (AP Photo/Alessandra Tarantino, File)

FILE - Nuns talk in front of Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo Buonarroti's Moses statue, part of a funerary monument he designed for Pope Julius II inside San Pietro in Vincoli Basilica in Rome, July 2, 2013. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia, File)

Cardinal Matteo Zuppi, centre, attends a mass on the third of nine days of mourning for late Pope Francis, in St. Peter's Basilica at the Vatican, Monday, April 28, 2025. (AP Photo/Andrew Medichini)

FILE - Cardinals walk in procession to the Sistine Chapel at the Vatican, at the beginning of the conclave, April 18, 2005. (Osservatore Romano via AP, File)