DNA, the magical molecule that carries all of the information for your physical characteristics, could soon reveal the look of your face.

A paper released on Monday by genomics-based company Human Longevity claims that it can predict individuals' faces by using their genomes.

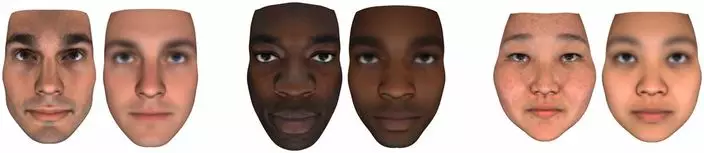

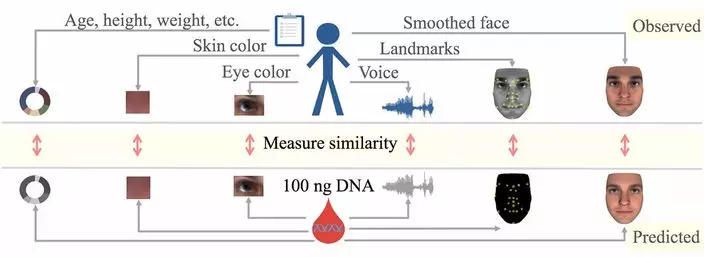

Researchers sequenced the whole genomes of 1,061 volunteers of varying ages and races, and feed their genomic and biometric information into a machine learning program.

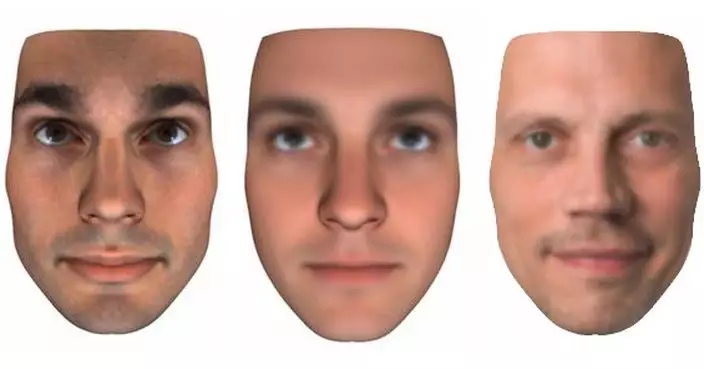

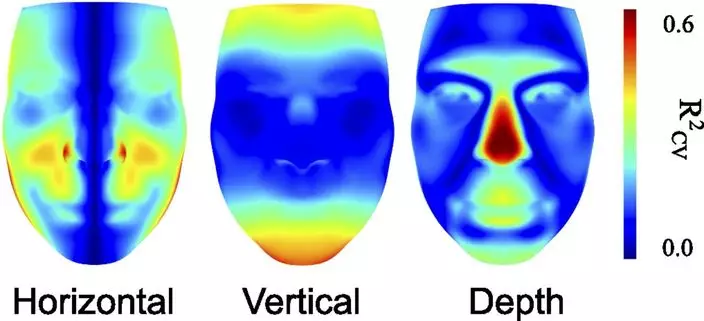

By analyzing given data, the program was able to construct a picture of a volunteer's face which indicates his or her gender, skin and eye color, facial structure, age, height, weight, and even voice.

The San Diego Union-Tribune reported the machine learning program could match anonymized genomes to their hosts with more than 80 percent accuracy in racially mixed groups. However, in groups of those with only European or African-American ancestry, the accuracy dived to 50 percent.

Results will be more accurate if more genomes are examined, said J. Craig Venter, executive chairman of Human Longevity and senior author of the paper. He also claimed that the study demonstrated higher accuracy in predicting simple characteristics such as skin and eye color, but tend to make more mistakes when it comes to complex traits like voice.

The genomics pioneer said, "I've always said to people that your genome is more than all the other numbers in your life that identify you: Your credit card number, your date of birth, your address, your Social Security number," The San Diego Union-Tribune reported.

Although the technology looks promising, some people are questioning its authenticity.

MIT Technology Review reported skeptics claim that the California-based company simply portrayed average looks of their volunteers based on their gender and races, which can be tested easily from DNA.

"The face prediction is just predicting the average face for your race. You will always say, 'Wow, that kind of looks like me,'" Jason Piper, genetics expert of Human Longevity told MIT Technology Review.

Yaniv Erlich, chief scientific officer of a genealogy website named MyHeritage.com said on Twitter that Venter's technology cannot predict face.

To prove his point, Erlich posted a picture of Venter's prediction of his own face from last year, saying that it looks more like actor Bradley Cooper than its host.