BIG PINE KEY, Fla. (AP) — The world's only Key deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer, are found in piney and marshy wetlands bordered by the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico on the Florida Keys. For years, their biggest threat was being struck by vehicles speeding along U.S. Highway 1 or local roads.

But those waters surrounding the islands now pose the biggest long-term risk for this herd of about 800 deer as sea rise jeopardizes their sole habitat.

Click to Gallery

The sun sets in the habitat of the Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, Thursday, Oct. 17, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

A Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, walks through a residential neighborhood, Thursday, Oct. 17, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, interact as they walk through a residential neighborhood Thursday, Oct. 17, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

This photo shows the habitat of the Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Daniel Kozin)

Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, walk along mangroves, Tuesday, Oct. 15, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

Pine trees, which have lost their needles, stand in the habitat of the Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

Chris Bergh, the South Florida program manager for the Nature Conservancy, walks in the habitat of the Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, Tuesday, Oct. 15, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

A road sign warns motorists not to speed in an area frequented by Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, walk in a residential neighborhood Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

This photo shows the habitat for the Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, Tuesday, Oct. 15, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Daniel Kozin)

A Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, walks past collected rainwater flowing from a drain in a residential neighborhood Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

Jan Svejkovsky, chief scientist for Save Our Key Deer, watches a Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, in front of his home, Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

A bucket of drinking water is left along a road for Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, Thursday, Oct. 17, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, walk in a residential neighborhood Tuesday, Oct. 15, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

A Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, walks in a residential neighborhood, Tuesday, Oct. 15, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

A Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, crosses the road Thursday, Oct. 17, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

These charismatic diminutive deer have been listed as endangered for almost 60 years after their numbers dipped to about 50 from hunting and poaching long ago. Yet they've made a tremendous comeback, with a peak population of about 1,000 in the mid-2010s before a deadly parasite and Hurricane Irma took a heavy toll.

However, experts and wildlife advocates say this conservation success story today is at risk of being undone by climate change. Sea level rise is already altering the landscape of Big Pine Key and at least 20 smaller islands the deer call home.

The bulk of the deer live on Big Pine Key, a marshy island 30 miles (48 kilometers) from Key West. They roam neighborhoods where about 4,500 people live, browsing on lush gardens and drinking water from buckets residents put out for them as natural freshwater supplies dwindle.

Key deer are far smaller than their North American counterparts, with the biggest bucks standing less than 3 feet (1 meter) tall at the shoulder and weighing around 75 pounds (34 kilograms).

“They were always vulnerable,” said Chris Bergh, the South Florida program manager for the Nature Conservancy, who oversees sea level rise projects and lives in Big Pine Key. “They’re much more vulnerable now. And with the sea level rising and their habitat shrinking, they’re becoming even more so.”

On Big Pine Key, mom and pop bars and restaurants dot either side of bustling U.S. 1, along with gas stations and small motels. The main industry revolves around the water — charter boats, fishing, diving, vacation rentals.

To protect the deer from being hit by vehicles, signs tell motorists they're entering deer habitat. A 2-mile (3.2-kilometer) stretch of U.S. 1 is elevated and fenced, allowing deer to cross under the road. And speed limits are strictly enforced, often frustrating tourists driving to Key West.

Deer still are struck at an alarming rate. “The bottom line is that some 90 to 120 deer are known to be killed by vehicles each year,” said Jan Svejkovsky, chief scientist for Save Our Key Deer.

Wildlife officials have worked hard get out the message: Don’t feed Key deer. They fear deer will approach cars and go near roadways for handouts.

Even with the traffic deaths, the population has remained stable. But a larger threat looms.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration projects that by 2100, seas will rise 1.5 feet to 7 feet (0.5 to 2 meters) in parts of the Florida Keys. The threat is greatest to low lying islands like Big Pine Key, where the highest point is only about 8 feet (2.4 meters) above sea level.

Sea rise will continue to shrink freshwater and food sources Key deer need to survive, experts say.

“So as the sea rises, that shrinks the amount of available freshwater, the amount of available, palatable vegetation, the places for bearing their young," said Bergh of the Nature Conservancy. "It puts them increasingly in conflict with people who are also occupying those higher grounds."

In addition to sea rise, climate change brings the threat of stronger hurricanes, with storm surges that can damage deer habitat and freshwater supplies.

Salt water intrusion also is responsible for killing many of the Florida slash pines that gave Big Pine Key its name. Mangroves are growing in their place in an ever-changing environment, choking deer habitat even more.

Key deer on Big Pine Key move through neighborhoods, munching on gardens. Some people even have names for ones that frequent their yards.

“They are very gentle, very, very gentle,” said Connie Ritchie, who sometimes sees about 30 deer a day. “And the longer you live here, the more you want to protect them. Big time. Protect them because they’re so innocent.”

“They have certain plants that they really love,” Ritchie said, noting that the federal deer refuge here hosts events where it gives away native plants. “So they’re trying to teach us to plant the plants that the deer won’t eat.”

Development on Big Pine Key began in the 1970s and 1980s “when entire swaths of land on islands that still held deer were developed into planned subdivisions, complete with saltwater canal networks to provide lot-buyers with direct water access,” said Svejkovsky of Save Our Key Deer.

While the key remains mostly rural with modest Florida bungalows and more palatial places, development has taken away some deer habitat.

”We have lots of people and the wildlife living in the same really concentrated area," said Katy Hosokawa, a park ranger at the National Key Deer Refuge, established in 1957 on 8,542 acres (3,457 hectares) of Big Pine Key. “So the more houses that we build, or the less lands that we have protected, the less areas that they have that are safe.”

The deer have adapted to the humans and move freely between wild spaces and the neighborhoods. "They roam, they spend their day grazing,” Hosokawa said. “We don’t have a really nutritionally dense soil, so they need to eat a lot of food to get what they need. But trust me, they’re very good at it. If it’s soft and tender, they will try to eat it.”

The future, while uncertain, looks grim.

Just six inches (15 centimeters) of sea rise, expected by 2030, would mean loss of 16% of the freshwater holes on Big Pine Key, said Nova Silvy, professor emeritus with Texas A&M University who has studied Key deer since 1968 and has lived here for several years.

By 2050, sea rise is expected to overtake about 84% of the 1,988 remaining acres (805 hectares) of the preferred habitat on Big Pine Key — and “the deer will already be gone,” Silvy said.

What happens if the deer can't survive in the Keys?

Bergh said he prefers to buy more time to keep the deer viable here. “And at some point, if that’s no longer possible, I personally think zoos are the most responsible alternative,” he said. “But that’s a terrible alternative. Who wants that for a wild animal?”

In rare instances, scientists have been allowed to relocate endangered species threatened by climate change as a last resort. But Silvy said, “The problem is if you take them any other place with deer, they’re going to interbreed and then you’ve lost the Key deer.”

Frisaro reported from Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

The sun sets in the habitat of the Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, Thursday, Oct. 17, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

A Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, walks through a residential neighborhood, Thursday, Oct. 17, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, interact as they walk through a residential neighborhood Thursday, Oct. 17, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

This photo shows the habitat of the Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Daniel Kozin)

Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, walk along mangroves, Tuesday, Oct. 15, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

Pine trees, which have lost their needles, stand in the habitat of the Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

Chris Bergh, the South Florida program manager for the Nature Conservancy, walks in the habitat of the Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, Tuesday, Oct. 15, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

A road sign warns motorists not to speed in an area frequented by Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, walk in a residential neighborhood Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

This photo shows the habitat for the Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, Tuesday, Oct. 15, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Daniel Kozin)

A Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, walks past collected rainwater flowing from a drain in a residential neighborhood Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

Jan Svejkovsky, chief scientist for Save Our Key Deer, watches a Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, in front of his home, Wednesday, Oct. 16, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

A bucket of drinking water is left along a road for Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, Thursday, Oct. 17, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, walk in a residential neighborhood Tuesday, Oct. 15, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

A Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, walks in a residential neighborhood, Tuesday, Oct. 15, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

A Key Deer, the smallest subspecies of the white-tailed deer that have thrived in the piney and marshy wetlands of the Florida Keys, crosses the road Thursday, Oct. 17, 2024, in Big Pine Key, Fla. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

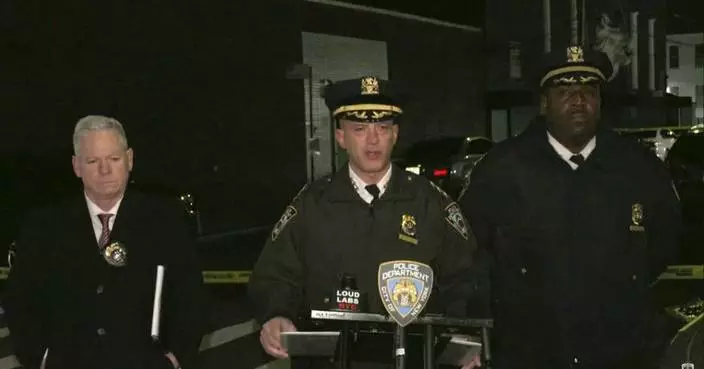

NEW ORLEANS (AP) — The U.S. Army veteran who drove a pickup truck into a crowd of New Year’s revelers acted alone, the FBI said Thursday, reversing its position from a day earlier that he likely worked with others in the deadly attack that officials said was inspired by the Islamic State group.

The FBI also revealed that the driver, Shamsud-Din Jabbar, a U.S. citizen from Texas, posted five videos on his Facebook account in the hours before the attack in which he proclaimed his support for the militant group and previewed the violence that he would soon unleash in the city's famed French Quarter district.

“This was an act of terrorism. It was premeditated and an evil act,” said Christopher Raia, the deputy assistant director of the FBI's counterterrorism division, calling Jabbar “100% inspired” by the Islamic State.

The attack killed 14 revelers, along with Jabbar, who was fatally shot in a firefight with police after steering his speeding truck around a barricade and plowing into the crowd.

It was the deadliest IS-inspired assault on U.S. soil in years, laying bare what federal officials have warned is a resurgent international terrorism threat. That threat is emerging as the FBI and other agencies brace for dramatic leadership upheaval after President-elect Donald Trump's administration takes office.

Seeking to assuage concerns about any broader plots, Raia stressed that there was no indication of a connection between the New Orleans attack and a Tesla Cybertruck explosion Wednesday outside Trump’s Las Vegas hotel.

The FBI continued to hunt for clues, but said that 24 hours into its investigation, it was now confident that the 42-year-old Jabbar was not aided by anyone else in the attack, which killed an 18-year-old aspiring nurse, a father of two and a former Princeton University football star.

Officials have reviewed surveillance video showing people standing near an improvised explosive device that Jabbar placed in a cooler along the city's Bourbon Street, where the attack occurred, but authorities “do not believe at this point these people are involved ... in any way,” Raia said.

Investigators were also trying to understand more about Jabbar's path to radicalization, which they say culminated with him picking up a rented truck in Houston on Dec. 30 and driving it to New Orleans the following night.

The FBI recovered a black Islamic State flag from his rented pickup and reviewed five videos posted to Facebook, including one in which he said he originally planned to harm his family and friends, but was concerned that news headlines would not focus on the “war between the believers and the disbelievers,” Raia said. He also left a last will and testament, the FBI said.

Jabbar joined the Army in 2007, serving on active duty in human resources and information technology and deploying to Afghanistan from 2009 to 2010, the service said. He transferred to the Army Reserve in 2015 and left in 2020 with the rank of staff sergeant.

Abdur-Rahim Jabbar, Jabbar's younger brother, told The Associated Press on Thursday that it “doesn’t feel real” that his brother could have done this.

“I never would have thought it’d be him,” he said. “It’s completely unlike him.”

He said that his brother had been isolated in the last few years, but that he had also been in touch with him and he didn’t see any signs of radicalization.

“It’s completely contradictory to who he was and how his family and his friends know him,” he said.

In New Orleans on Thursday, a still-reeling city inched back toward normal operations. Authorities finished processing the scene early in the morning, removing the last of the bodies, and Bourbon Street was set to reopen at some point later in the day, according to an official familiar with the matter who spoke on condition of anonymity to the AP.

The Sugar Bowl college football game between Notre Dame and Georgia, initially set for Wednesday night and postponed by a day in the interest of national security, was still on for Thursday. The city planned to host the Super Bowl next month.

“This is one of the safest places on earth," Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry said. "It doesn’t mean that nothing can't happen.”

Tucker reported from Washington, and Mustian reported from Black Mountain, North Carolina. Associated Press reporters Stephen Smith, Chevel Johnson and Brett Martel in New Orleans; Jeff Martin in Atlanta; Alanna Durkin Richer, Tara Copp and Zeke Miller in Washington; Darlene Superville in New Castle, Delaware; Colleen Long in West Palm Beach, Florida; and Michael R. Sisak in New York contributed to this report.

Flowers are seen near where a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon streets, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

A man uses a power washer on Toulouse street a day after a vehicle was driven into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon streets, Thursday, Jan. 2, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Security with bomb sniffing dogs patrol the area around the Superdome ahead of the Sugar Bowl NCAA College Football Playoff game, Thursday, Jan. 2, 2025, in New Orleans. (AP Photo/Butch Dill)

Military personnel walk down Bourbon street, Thursday, Jan. 2, 2025 in New Orleans. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

People react at the intersection of Bourbon Street and Canal Street during the investigation after a pickup truck rammed into a crowd of revelers early on New Year's Day, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025, in New Orleans. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)

Police officers stand near the scene where a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon streets, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Matthias Hauswirth of New Orleans prays on the street near the scene where a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon streets, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

This undated passport photo provided by the FBI on Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025, shows Shamsud-Din Bahar Jabbar. (FBI via AP)

Emergency services attend the scene after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

The FBI investigates the area on Orleans St and Bourbon Street by St. Louis Cathedral in the French Quarter where a suspicious package was detonated after a person drove a truck into a crowd earlier on Bourbon Street on Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)

The FBI investigates the area on Orleans St and Bourbon Street by St. Louis Cathedral in the French Quarter where a suspicious package was detonated after a person drove a truck into a crowd earlier on Bourbon Street on Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)

A New Orleans police officer searches the area near a crime scene after a vehicle drove into a crowd on Canal and Bourbon Street earlier, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Jack Brook)

EDS NOTE: GRAPHIC CONTENT - Emergency personnel work the scene on Bourbon Street after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Investigators work the scene after a person drove a vehicle into a crowd killing several, earlier on Canal and Bourbon Street in New Orleans, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

New Orleans mayor LaToya Cantrell makes a statement after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

A mounted police officer arrives on Canal Street after a vehicle drove into a crowd earlier in New Orleans, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Kevin McGill)

A police barricade near the scene after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Emergency services attend the scene after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

The scene after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Emergency services attend the scene on Bourbon Street after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

The St. Louis Cathedral is seen on Orleans St is seen in the French Quarter where a suspicious package was detonated after a person drove a truck into a crowd earlier on Bourbon Street on Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)

Emergency services attend the scene on Bourbon Street after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Investigators work the scene after a person drove a vehicle into a crowd earlier on Canal and Bourbon Street in New Orleans, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Trevant Hayes, 20, sits in the French Quarter after the death of his friend, Nikyra Dedeaux, 18, after a pickup truck crashed into pedestrians on Bourbon Street followed by a shooting in the French Quarter in New Orleans, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)

A black flag with white lettering lies on the ground rolled up behind a pickup truck that a man drove into a crowd on Bourbon Street in New Orleans, killing and injuring a number of people, early Wednesday morning, Jan. 1, 2025. The FBI said they recovered an Islamic State group flag, which is black with white lettering, from the vehicle. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Emergency services attend the scene after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Security personnel gather at the scene on Bourbon Street after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

EDS NOTE: GRAPHIC CONTENT - Security personnel investigate the scene on Bourbon Street after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

The FBI investigates the area on Orleans St and Bourbon Street by St. Louis Cathedral in the French Quarter where a suspicious package was detonated after a person drove a truck into a crowd earlier on Bourbon Street on Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)

Edward Bruski, center, gets emotional at the scene where a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

FBI members examine the scene on Bourbon Street during the investigation of a truck fatally crashing into pedestrians on Bourbon Street in the French Quarter in New Orleans, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)

Emergency service vehicles form a security barrier to keep other vehicles out of the French Quarter after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Members of the FBI walk around Bourbon Street during the investigation of a truck fatally crashing into pedestrians on Bourbon Street in the French Quarter in New Orleans, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)