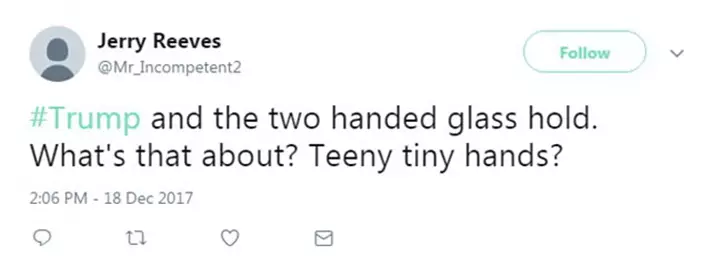

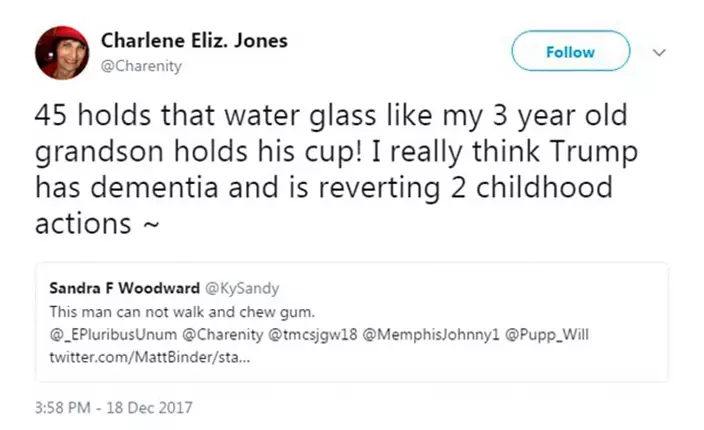

Really dementia or too childish only?

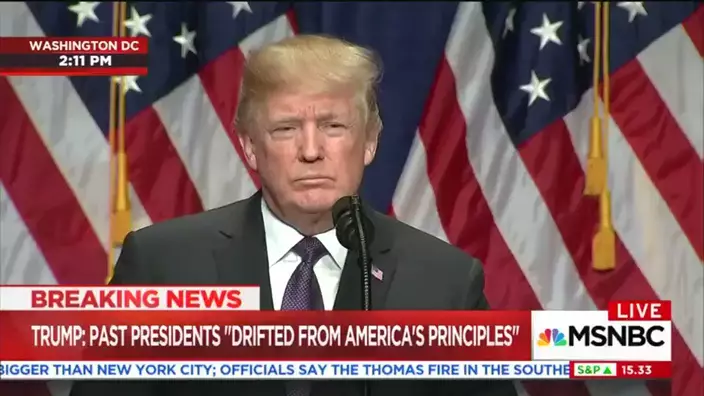

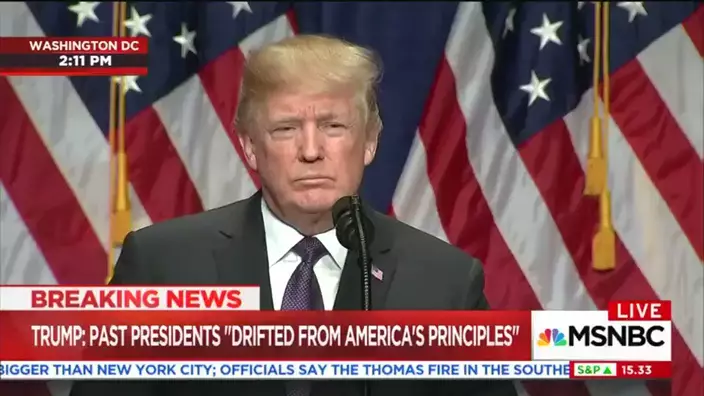

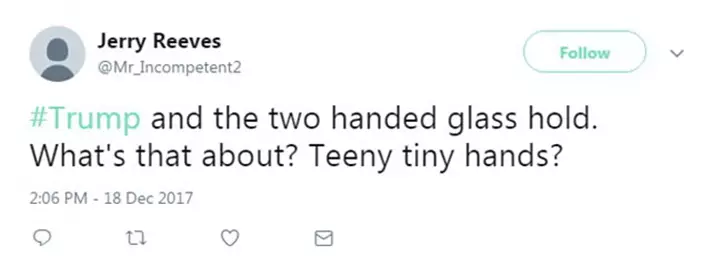

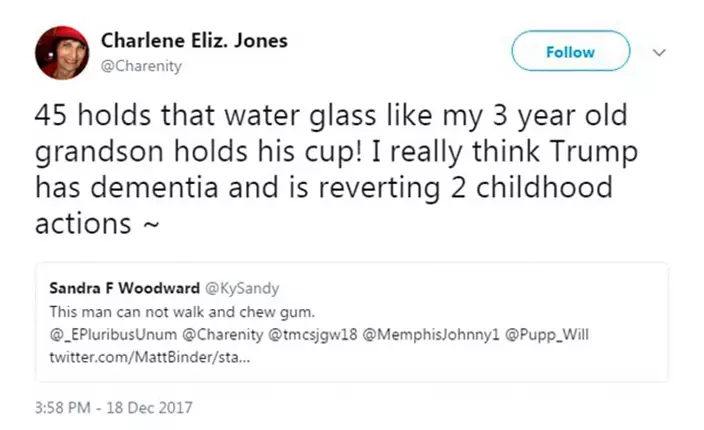

Donald Trump has kindled dementia concerns when he used two hands to hold a small glass of water during an Israel policy speech.

Photo via Twitter

Photo via Twitter

People posted pictures and videos on Twitter since Monday after the US president took an awkward pose of drinking water while introducing his new national security strategy in front of military service members in Washington, D.C.

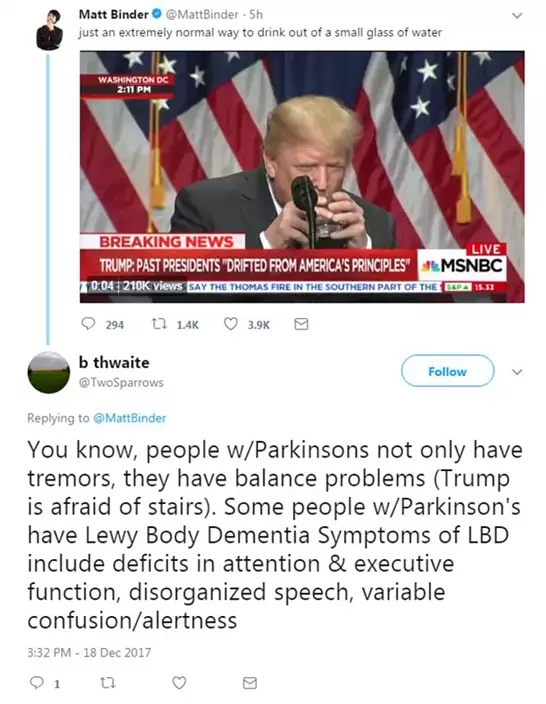

Sandra F Woodward said, "Trump holds that water glass like my 3-year-old grandson holds his cup! I really think Trump has dementia and is reverting 2 childhood action."

And there are a lot of comments agree with the comments.

It seems this is not a single incident indicating the illness. In November, he picked up a bottle of water using both hands and sipped it unnaturally during a press conference at the White House.

Photo via Twitter

Earlier this month, after he gave his speech announcing changes to America's Isreal policy, he finished his remarks by saying, "God bless the United Shhtates. Thank you very much-sh."

Some theorists, including Democratic partisans, point out every possibility on Twitter from a mini-stroke to cocaine use.

TV host Joe Scarborough also said, "people close to him during the campaign told me he had early stages of dementia"

Some people criticized he is like a child.

Photo via Twitter

Photo via Twitter

Photo via Twitter

Photo via Twitter

The speech has even reignited the rumors of Trump's health.

A White House spokesman insisted the president just had a "dry month" and "There's nothing to it."

When asked if Trump had any related health concerns, she said, "I know what you're getting at. I'm saying there's nothing to it."

Much evidence shows he was not like this before.

Photo via Twitter

Photo via Twitter

Even Trump may be facing health concerns, some netizens still may jokes on him by comparing him to the former President Obama and a lovely squirrel.

Photo via Twitter

DETROIT (AP) — At the U.S. Embassy in Ottawa, a quote from former President Ronald Reagan is engraved on one wall.

“Let the 5,000-mile border between Canada and the United States stand as a symbol for the future," Reagan said upon signing a 1988 free trade pact with America’s northern neighbor. "Let it forever be not a point of division but a meeting place between our great and true friends.”

But a point of division is here. On Tuesday, President Donald Trump plans to impose a 25% tariff on most imported Canadian goods and a 10% tariff on Canadian oil and gas. Mexico is also facing a 25% tariff.

Canada has said it will retaliate with a 25% import tax on a multitude of American products, including wine, cigarettes and shotguns.

The tariffs have touched off a range of emotions along the world’s longest international border, where residents and industries are closely intertwined. Ranchers in Canada rely on American companies for farm equipment, and export cattle and hogs to U.S. meat processors. U.S. consumers enjoy thousands of gallons of Canadian maple syrup each year. Canadian dogs and cats dine on U.S.-made pet food.

The trade dispute will have far-reaching spillover effects, from price increases and paperwork backlogs to longer wait times at the U.S.-Canada border for both people and products, said Laurie Trautman, director of the Border Policy Research Institute at Western Washington University.

“These industries on both sides are built up out of a cross-border relationship, and disruptions will play out on both sides,” Trautman said.

Even the threat of tariffs may have already caused irreparable harm, she said. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has urged Canadians to buy Canadian products and vacation at home.

The Associated Press wanted to know what residents and businesses were thinking along the border that Reagan vowed would remain unburdened by an “invisible barrier of economic suspicion and fear.” Here’s what they said:

People flocked from the boomtown of Skagway, Alaska, to Canada’s Yukon in search of riches during the Klondike gold rush of the late 1890s, following routes that Indigenous tribes long used for trade.

Today, Skagway trades on its past, drawing more than 1 million cruise ship passengers a year to a historic downtown that features Klondike-themed museums. But the municipality with a population of about 1,100 still holds deep ties to the Yukon.

Skagway residents frequently travel to Whitehorse, the territory's capital, for a wider selection of groceries and shopping, dental care, veterinary services and swimming lessons. The Alaskan city's port, meanwhile, still supports Yukon mining and is a critical hub for fuel and other essentials both communities need.

“It’s a special connection,” Orion Hanson, a contractor and Skagway Assembly member, said of Whitehorse, which sits 110 miles (177 kilometers) north and has 30,000 people. “It’s really our most accessible neighbor.”

Hanson is concerned about what tariffs might mean for the price of building supplies, such as lumber, concrete and steel. The cost of living in small, remote places already is high. People in Whitehorse and Skagway worry about the potential impact on community relations as well as prices.

Norman Holler, who lives in Whitehorse, said the months the tariffs have loomed created “an uncomfortable feeling and resentment.” If the threat becomes reality, Holler said he would probably still visit Alaska border towns but not other parts of the United States.

““Is it rational? I don’t know, but it satisfies an emotional need not to go,” he said.

- Becky Bohrer in Juneau, Alaska

At the border of Washington state and British Columbia, the tension over tariffs is evident in a waterfront community that is hoping for Canadian mercy.

Point Roberts is a 5-square-mile (13-square kilometer) U.S. exclave whose only land connection lies in Canada, which supplies the unincorporated nub of American soil its water and electricity. It’s a geographic oddity that requires a 20-mile drive around Canada to reach mainland Washington state.

Local real estate agent Wayne Lyle, who like many of his neighbors has dual U.S.-Canadian citizenship, said some of Point Roberts’ roughly 1,000 residents are signing a petition pleading with British Columbia's premier for an exemption to whatever retaliatory tariffs Canada may institute.

“We’re basically connected to Canada. We’re about as Canadian as an American city can be,” Lyle said. “We’re unique enough that maybe we can get a break.”

Lyle, who serves as the president of the Point Roberts Chamber of Commerce, said it’s too early to identify measurable effects, but he fears Canadians won’t visit the popular summer getaway destination out of spite.

“We don’t want Canada to think we’re the bad guys,” Lyle said. “Please don’t take it out on us.”

- Sally Ho in Seattle

The 545-mile (877-kilometer) stretch of land that separates Montana from Canada includes some of the sleepiest checkpoints on the binational border. Several of the state's border posts had fewer than 50 crossings a day on average last year.

But unseen, in underground pipelines that cut through vast fields of barley, flows about $5 billion annually worth of Canadian crude oil and natural gas, most of it from Alberta. The lines traverse a continental pivot point -- Montana is the only state with rivers that drain into the Pacific Ocean, Gulf of Mexico and Canada’s Hudson Bay – and deliver to refineries around Billings.

“Canada is one of our major supply sources for oil across the United States,” said Dallas Scholes, the government affairs director of Houston-based refinery company Par Pacific, which runs a processing facility along the Yellowstone River. “If tariffs are imposed on the oil and gas industry, … it’s not going to be good for consumers.”

People in Montana drive long distances given its sprawling size and burn lots of natural gas through harsh winters, making its residents the highest energy consumers per capita in the U.S., according to federal data.

That means a 10% tax on Canadian energy resources would be felt broadly. The state’s farmers would be among those hit more severely, given the large volumes of gasoline needed to run tractors and other equipment, according to Jeffrey Michael, director of the University of Montana’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research.

“It will be painful, but there are larger concerns if I were an agricultural producer in Montana,” Michael said. “I’d be worried about the trade war escalating to where my products start to get hit with reciprocal tariffs."

- Matthew Brown in Billings, Mont.

The Detroit River is all that separates Windsor, Ontario, from Detroit. The cities are so close that Detroiters can smell the drying grain at Windsor’s Hiram Walker distillery and Windsor can hear the music drifting from Detroit’s outdoor concert venues.

Manufacturing muscle makes the Ambassador Bridge, the 1.4-mile-long span connecting the two cities, the busiest international crossing in North America. According to the Michigan company that owns the bridge, $323 million worth of goods travel each day between Windsor and Detroit, the automotive capitals of their countries.

The U.S., Canada and Mexico have long operated as one nation when it comes to auto manufacturing, noted Pat D’Eramo, CEO of Vaughan, Ontario-based automotive suppler Martinrea. Tariffs will cause confusion and disruption, he said.

Right now, steel coils arrive at a plant in Michigan and get stamped into parts that are shipped to Martinrea in Canada. Martinrea uses the parts to build vehicle sub-assemblies that get shipped back to an automaker in Detroit.

A White House official told The Associated Press that parts would be taxed twice if they crossed the border multiple times, but it's unclear if suppliers or their customers will have to pay for the tariffs. Also unclear is how a separate 25% levy on steel and aluminum that Trump said would take effect starting March 12 factors into the mix.

D’Eramo understands the impulse to strengthen U.S. manufacturing but says the U.S. doesn’t have the capacity to make all the tooling Martinrea would need if it were to shift production there. At the end of the day, he thinks it’s sad tariffs will take up so much time, energy and resources, and only make vehicles even more expensive.

“We need to be spending our time and money to get more efficient and reduce our costs so customers can reduce their costs,” he said.

-Dee-Ann Durbin in Detroit

Buffalo, New York is, decidedly, a beer town. It’s also a border town.

That makes for a complementary relationship. Western New York’s dozens of craft breweries rely on Canada for aluminum cans and much of the malted grain that goes into their brews. Canadians regularly cross one of the four international bridges into the region to shop, go to sporting events and sip Buffalo's beers.

Brewers and other businesses fear there may be less of that, though, if the tariffs on Canada and aluminum go into effect. Trump's repeated comments about making the neighboring nation the 51st U.S. state already offended its citizens - so much so that Buffalo’s tourism agency paused a campaign running in Canada because of negative comments.

“Obviously, having a bad taste in their mouth and booing the national anthem at sporting events is not a great thing for them coming down here and drinking our beer and hanging out in our city,” said Jeff Ware, president of Resurgence Brewing Co.

The historic factory building housing Ware’s business in Buffalo is about 4 miles from the Peace Bridge border crossing, where 1.8 million cars and buses and 518,000 commercial trucks entered Buffalo from Ontario last year.

It’s a terrible time to alienate customers, Canadian or American. The snowy first months of the year are hard enough for Buffalo’s breweries, Ware said. Higher prices from 25% tariffs would be yet another obstacle. Ware gets about 80% of the base malt be uses to make his specialty beers from Canada.

“Labor is more expensive, energy is more expensive, all of our raw ingredients are more expensive,” he said. “It’s death by a thousand cuts.”

- Carolyn Thompson in Buffalo, N.Y.

Commercial lobsterman John Drouin has fished for Maine’s signature seafood for more than 45 years, often in disputed waters known as the “grey zone” that straddle the U.S.-Canada border.

The relationship between American and Canadian fishermen can sometimes be fraught, but harvesters on both side of the border know they depend on each other, Drouin said. Maine fishermen catch millions of pounds of lobsters every year, but much of the processing capacity for the valuable crustaceans is in Canada.

If Trump follows through with the threatened tariffs next week, lobsters sent to Canada for processing would be subject to customs duties when they return to the U.S. to go to market. Drouin fears what will happen to the lobster industry if the trade dispute persists and Canada enacts a retaliatory tariff on lobsters.

“As the price goes up to the consumer, there comes a point where it just doesn’t become palatable for them to purchase it,” Drouin said.

Drouin, 60, fishes out of Cutler, Maine, and sees Grand Manan Island, an island in the Bay of Fundy that is part of the province of New Brunswick, when he takes his boat out. He described his business as “right smack on the Canadian border” in terms of both economics and geography.

He described himself as a fan of Trump’s first term who is “not overly thrilled with what he’s been doing here.” And he said he’s concerned his home state could ultimately be hurt by the tariffs if the president isn’t mindful of border industries such as his.

“The rhetoric is a bit much, what’s taking place,” Drouin said.

- Patrick Whittle in Scarborough, Maine

FILE- A lobstermen unties his boat before heading out to fish in Jonesport, Maine, April 27, 2023. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty, files)

FILE - Lobster boats sit at their moorings in Jonesport, Maine, April 28, 2023. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty, files)

Lobsterman John Drouin, who fishes waters on the border between the United States and Canada, expresses his views on how President Trump's planned tariffs will create new challenges for both country's fishing industry, Thursday, Feb. 27, 2025, in Rockport, Maine. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

Old silos are repainted to look like Labatt Blue cans, Thursday, Feb. 27, 2025, in Buffalo, N.Y. (AP Photo/Lauren Petracca)

Jeff Ware, president of Resurgence Brewing Company, poses for a portrait near a stockpile of aluminum cans, which are sourced from Canada, Thursday, Feb. 27, 2025, in Buffalo, N.Y. (AP Photo/Lauren Petracca)

The Peace Bridge connects the United States and Canada, Thursday, Feb. 27, 2025, in Buffalo, N.Y. (AP Photo/Lauren Petracca)

Trucks enter into the United States from Ontario, Canada across the Ambassador Bridge, Monday, Feb. 3, 2025, in Detroit. (AP Photo/Paul Sancya)

The Par Montana refinery along the Yellowstone River that processes crude oil from western Canada is seen, Wednesday, Feb. 26, 2025, just outside Billings, Mont. (AP Photo/Matthew Brown)

Visitors take pictures of the United States-Canada border marker on the Point Roberts Maple Beach, Saturday, March 1, 2025, in Point Roberts, Wash. (AP Photo/Ryan Sun)

A cashier at the International Market in Point Roberts displays a till for U.S. Dollars and Canadian Dollars, Saturday, March 1, 2025, in Point Roberts, Wash. (AP Photo/Ryan Sun)

People walk along Maple Beach ahead of a buoy demarcating the United States-Canada border, Saturday, March 1, 2025, in Point Roberts, Wash. (AP Photo/Ryan Sun)

FILE - Visitors walk in the downtown area of Skagway, Alaska, Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Thiessen, File)

People gather along the streets of Skagway, Alaska, for a Fourth of July parade Tuesday, July 4, 2023. (Andrew Cremata via AP)

FILE - Washington State Park workers put up a new Canadian flag in front of an American flag about to be replaced during scheduled maintenance atop the Peace Arch in Peace Arch Historical State Park Monday, Nov. 8, 2021, in Blaine, Wash. (AP Photo/Elaine Thompson, File)