WARNING: GRAPHIC CONTENT – Michael Rogers was at risk of losing his leg because of complications related to his diabetes.

A former council worker has praised maggots for performing a “medical miracle” – by feasting on a gaping mass of infected tissue and bone marrow and saving his ulcerated foot from amputation.

Click to Gallery

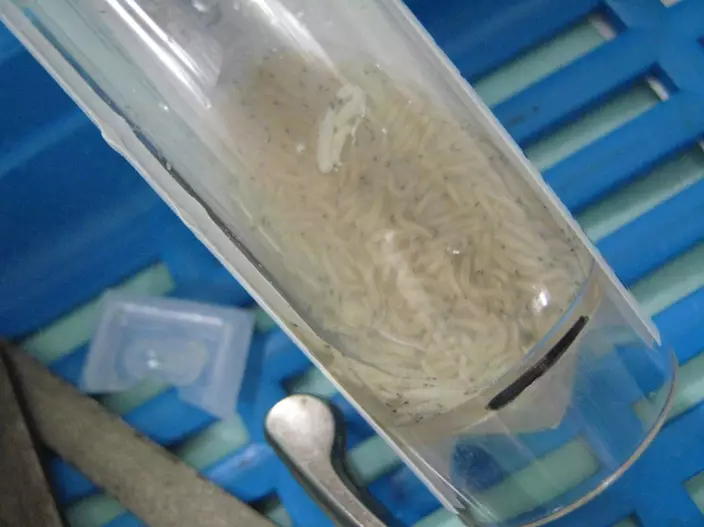

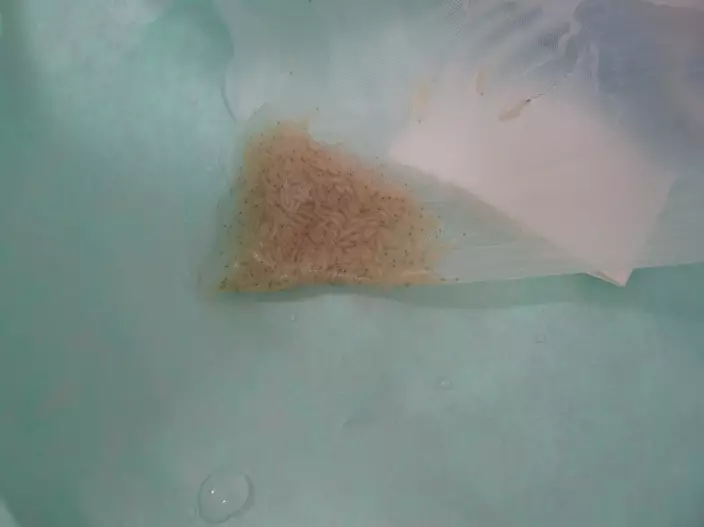

The maggots eat away the dead flesh and disinfect the wound with their cleansing saliva (Collect/PA Real Life)

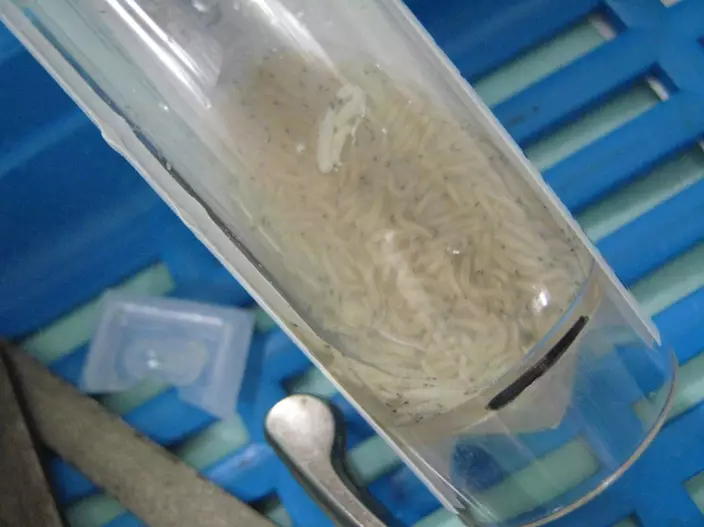

The maggots are specially farmed for medical purpose (Collect/PA Real Life)

Michael at home in Swansea (Collect/PA Real Life)

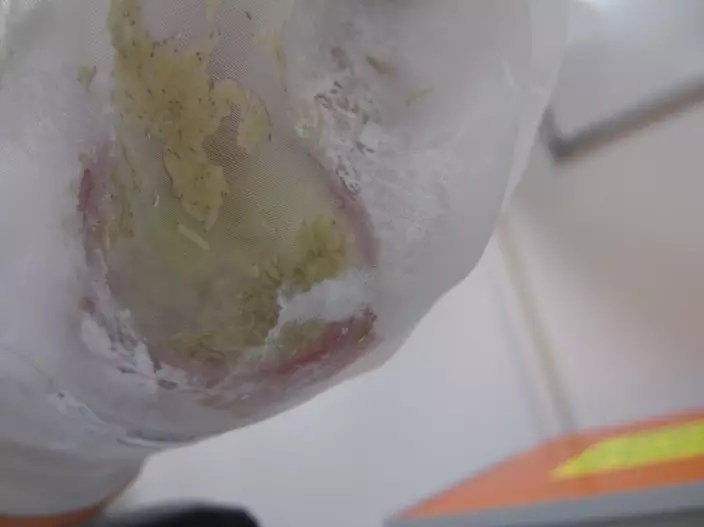

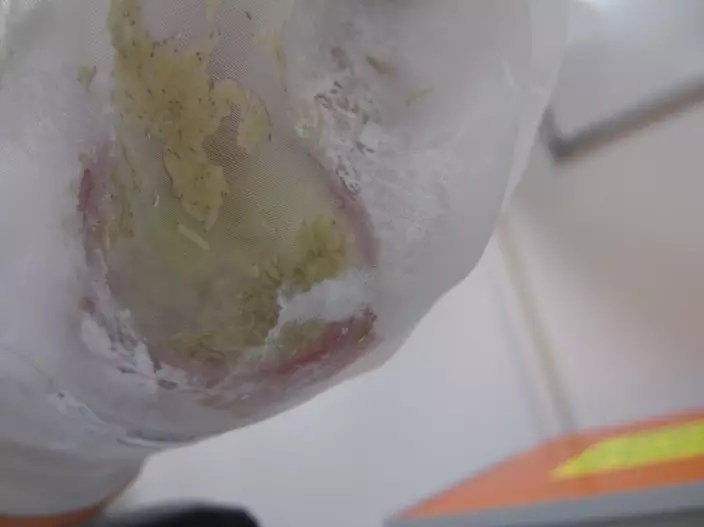

GRAPHIC WARNING Michael's infected foot before the maggots had been applied (Collect/PA Real Life)

Michael's heel with the maggots in situ beneath a gauze (Collect/PA Real Life)

Michael has used a wheelchair since the infection in his foot started last year (Collect/PA Real Life)

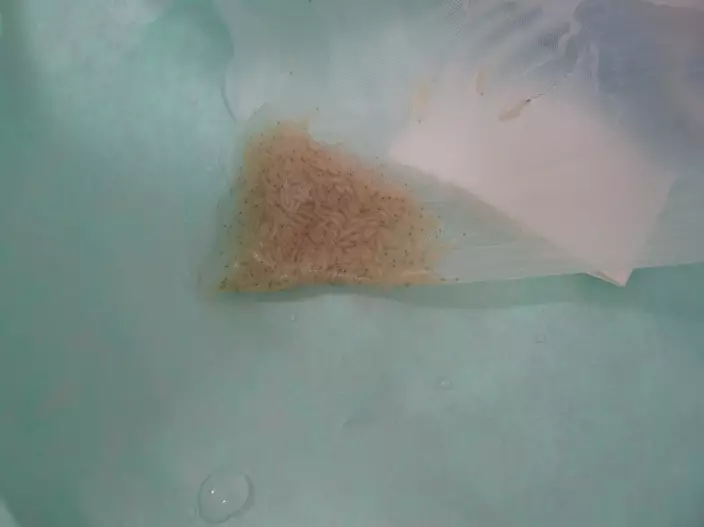

The maggots are kept in place on the wound using gauze material (Collect/PA Real Life)

GRAPHIC WARNING Michael's foot after two bouts of maggot therapy (Collect/PA Real Life)

GRAPHIC WARNING Michael in Morriston hospital receiving treatment (Collect/PA Real Life)

Michael Rogers, 64, who lost his right leg in 2015, as a result of diabetic complications, was then forced to have 80 per cent of his left heel cut away last year, after blood flow and nerve problems, common to the condition, meant his tissue turned black and died.

Left with a 14cm by 10cm wound on the sole of his foot and fearing he would lose the rest of it, single Michael, of Swansea, West Glamorgan, South Wales, said his saviour came in April 2018 – in the form of hundreds of specially farmed green-bottle maggots.

The maggots eat away the dead flesh and disinfect the wound with their cleansing saliva (Collect/PA Real Life)

After having the creepy crawlies attached to his wound for two week-long stints, as part of a radical treatment programme, Michael said: “I owe those little fellas a lot!

“I was adamant that I wasn’t going to lose another leg and was willing to do anything to keep it.

“The doctors tried various things that hadn’t worked, trying to get rid of the dead and infected tissue in my foot.”

The maggots are specially farmed for medical purpose (Collect/PA Real Life)

He added: “So, when they suggested to me the maggots, without hesitation I said, ‘Bring it on!'”

Diagnosed with type 2 diabetes 12 years ago, meaning the body either does not produce enough insulin, or its cells do not react to insulin, Michael first began having serious complications as a result of the condition that affects blood flow and blood sugar levels, in 2015.

He was diagnosed with osteomyelitis – a serious infection of the bone, known to be a common complication of diabetic foot ulcers – in his right foot, leading to a below knee amputation.

Michael at home in Swansea (Collect/PA Real Life)

Then, just two years later, he was devastated to be told that osteomyelitis had now developed in his left foot.

“I thought to myself, ‘Here we go again,'” said Michael, who recalled experiencing pain and seeing his skin blacken within a few days.

“I knew what it was, but this time I really did not want to lose my leg and was determined to keep it.”

GRAPHIC WARNING Michael's infected foot before the maggots had been applied (Collect/PA Real Life)

But, within six months of having the maggot therapy, his wound had shrunk to just 3cm by 1cm, as the wriggly critters had gorged on all the dead skin, simultaneously disinfecting the wound.

Now, on the road to a full recovery, Michael is an enthusiastic supporter of the treatment, saying: “I would recommend the maggots to anyone.

“Admittedly, I had a bit of trepidation about having these things crawling around on my body for such long periods of time, while I was at home, trying to get on with my life and in bed at night, while I was sleeping.”

Michael's heel with the maggots in situ beneath a gauze (Collect/PA Real Life)

He added: “But they were marvellous and really helped to sort me out.”

With the infection inside his bone and deep within the tissue of his foot, doctors at Swansea’s Morriston Hospital had first conducted debridement surgery, to remove dead matter, in August 2017 – resulting in cutting away 80 per cent of his heel.

Despite their best efforts, though, some of the infection still remained, which if left untreated could spread further, making amputation the only option.

Michael has used a wheelchair since the infection in his foot started last year (Collect/PA Real Life)

“The doctors told me they’d have to start thinking of alternatives, one of which was vacuum therapy, where they tried to suck out the dead tissue,” he said.

“Unfortunately, though, that didn’t work enough and by this stage the wound in my foot was quite big. That’s when they suggested that maggots could be the answer.”

Applied on two separate occasions in April 2018, Michael’s foot was then wrapped in gauze, “like a teabag,” according to Michael, before the maggots were attached to the wound on his heel.

The maggots are kept in place on the wound using gauze material (Collect/PA Real Life)

Left on for a week at a time, confined within the bandages, they were able to eat away, painlessly, at the dead flesh.

“I really couldn’t feel a thing, but it was a little odd to think that I had these foreign bodies eating away at a part of my body while I was going about my daily business,” he said.

The maggots – which grew in size as they chomped their way through his dead foot – were a huge success.

GRAPHIC WARNING Michael's foot after two bouts of maggot therapy (Collect/PA Real Life)

Now Michael, who is currently using a wheelchair, says he is recovering well, adding: “Hopefully I won’t be wheelchair-bound for much longer and I’ll be back up on my feet again, using a prosthetic.

“But in any case, those maggots helped me out an awful lot and I feel genuinely grateful to them and the hospital for suggesting it.

“I know a lot of people will have negative preconceptions about maggots and would turn their noses up at the idea – but my advice would be give it a go. No matter how grisly something might seem, if it can help get you out of trouble then it has to be worth it.”

GRAPHIC WARNING Michael in Morriston hospital receiving treatment (Collect/PA Real Life)

Meanwhile, Rosalyn Thomas, a podiatry specialist at Morriston Hospital who did the treatment, praised the use of maggots to treat these kind of wounds.

She said: “There are many benefits to using maggot therapy.

“They are efficient and cost effective and patients and they can clean wounds in two or three days leaving healthy tissue to allow wound healing to progress as their saliva has antibiotic properties that help keep the wound clean. They are really like blind legless surgeons!”

KYIV, Ukraine (AP) — Desertion is starving the Ukrainian army of desperately needed manpower and crippling its battle plans at a crucial time in its war with Russia, which could put Kyiv at a clear disadvantage in future ceasefire talks.

Facing every imaginable shortage, tens of thousands of Ukrainian troops, tired and bereft, have walked away from combat and front-line positions to slide into anonymity, according to soldiers, lawyers and Ukrainian officials. Entire units have abandoned their posts, leaving defensive lines vulnerable and accelerating territorial losses, according to military commanders and soldiers.

Some take medical leave and never return, haunted by the traumas of war and demoralized by bleak prospects for victory. Others clash with commanders and refuse to carry out orders, sometimes in the middle of firefights.

“This problem is critical,” said Oleksandr Kovalenko, a Kyiv-based military analyst. “This is the third year of war, and this problem will only grow.”

Although Moscow has also been dealing with desertions, Ukrainians going AWOL have laid bare deeply rooted problems bedeviling their military and how Kyiv is managing the war, from the flawed mobilization drive to the overstretching and hollowing out of front-line units. It comes as the U.S. urges Ukraine to draft more troops, and allow for the conscription of those as young as 18.

The Associated Press spoke to two deserters, three lawyers, and a dozen Ukrainian officials and military commanders. Officials and commanders spoke on condition of anonymity to divulge classified information, while one deserter did so because he feared prosecution.

“It is clear that now, frankly speaking, we have already squeezed the maximum out of our people,” said an officer with the 72nd Brigade, who noted that desertion was one of the main reasons Ukraine lost the town of Vuhledar in October.

More than 100,000 soldiers have been charged under Ukraine’s desertion laws since Russia invaded in February 2022, according to the country’s General Prosecutor’s Office.

Nearly half have gone AWOL in the last year alone, after Kyiv launched an aggressive and controversial mobilization drive that government officials and military commanders concede has largely failed.

It's a staggeringly high number by any measure, as there were an estimated 300,000 Ukrainian soldiers engaged in combat before the mobilization drive began. And the actual number of deserters may be much higher. One lawmaker with knowledge of military matters estimated it could be as high as 200,000.

Many deserters don't return after being granted medical leave. Bone-tired by the constancy of war, they are psychologically and emotionally scarred. They feel guilt about being unable to summon the will to fight, anger over how the war effort is being led, and frustration that it seems unwinnable.

“Being quiet about a huge problem only harms our country,” said Serhii Hnezdilov, one of few soldiers to speak publicly about his choice to desert. He was charged shortly after the AP interviewed him in September.

Another deserter said he initially left his infantry unit with permission because he needed surgery. By the time his leave was up, he couldn’t bring himself to return.

He still has nightmares about the comrades he saw get killed.

“The best way to explain it is imagining you are sitting under incoming fire and from their (Russian) side, it’s 50 shells coming toward you, while from our side, it’s just one. Then you see how your friends are getting torn to pieces, and you realize that any second, it can happen to you,” he said.

“Meanwhile guys (Ukrainian soldiers) 10 kilometers (6 miles) away order you on the radio: ‘Go on, brace yourselves. Everything will be fine,’” he said.

Hnezdilov also left to seek medical help. Before undergoing surgery, he announced he was deserting. He said after five years of military service, he saw no hope of ever being demobilized, despite earlier promises by the country’s leadership.

“If there’s no end term (to military service), it turns into a prison – it becomes psychologically hard to find reasons to defend this country,” Hnezdilov said.

Desertion has turned battle plans into sand that slips through military commanders' fingertips.

The AP learned of cases in which defensive lines were severely compromised because entire units defied orders and abandoned their positions.

“Because of a lack of political will and poor management of troops, especially in the infantry, we certainly are not moving in a direction to properly defend the territories that we control now,” Hnezdilov said.

Ukraine’s military recorded a deficit of 4,000 troops on the front in September owing largely to deaths, injuries and desertions, according to a lawmaker. Most deserters were among recent recruits.

The head of one brigade’s legal service who is in charge of processing desertion cases and forwarding them to law enforcement said he's had many of them.

“The main thing is that they leave combat positions during hostilities and their comrades die because of it. We had several situations when units fled, small or large. They exposed their flanks, and the enemy came to these flanks and killed their brothers in arms, because those who stood on the positions did not know that there was no one else around,” the official said.

That is how Vuhledar, a hilltop town that Ukraine defended for two years, was lost in a matter of weeks in October, said the 72nd Brigade officer, who was among the very last to withdraw.

The 72nd was already stretched thin in the weeks before Vuhledar fell. Only one line battalion and two rifle battalions held the town near the end, and military leaders even began pulling units from them to support the flanks, the officer said. There should have been 120 men in each of the battalion’s companies, but some companies' ranks dropped to only 10 due to deaths, injuries and desertions, he said. About 20% of the soldiers missing from those companies had gone AWOL.

“The percentage has grown exponentially every month,” he added.

Reinforcements were sent once Russia wised up to Ukraine's weakened position and attacked. But then the reinforcements also left, the officer said. Because of this, when one of the 72nd Brigade battalions withdrew, its members were gunned down because they didn't know no one was covering them, he said.

Still, the officer harbors no ill will toward deserters.

“At this stage, I do not condemn any of the soldiers from my battalion and others. … Because everyone is just really tired,” he said.

Prosecutors and the military would rather not press charges against AWOL soldiers and do so only if they fail to persuade them to return, according to three military officers and a spokesperson for Ukraine’s State Investigative Bureau. Some deserters return, only to leave again.

Ukraine's General Staff said soldiers are given psychological support, but it didn't respond to emailed questions about the toll desertions are having on the battlefield.

Once soldiers are charged, defending them is tricky, said two lawyers who take such cases. They focus on their clients' psychological state when they left.

“People cannot psychologically cope with the situation they are in, and they are not provided with psychological help,” said attorney Tetyana Ivanova.

Soldiers acquitted of desertion due to psychological reasons set a dangerous precedent because “then almost everyone is justified (to leave), because there are almost no healthy people left (in the infantry),” she said.

Soldiers considering deserting have sought her advice. Several were being sent to fight near Vuhledar.

“They would not have taken the territory, they would not have conquered anything, but no one would have returned,” she said.

FILE - In this photo provided by Ukraine's 24th Mechanised Brigade press service, servicemen of the 24th Mechanised Brigade install anti-tank landmines and non explosive obstacles along the front line near Chasiv Yar town in Donetsk region, Ukraine, on Oct. 30, 2024. (Oleg Petrasiuk/Ukrainian 24th Mechanised Brigade via AP, File)

FILE - Volodymyr, a 51 year old soldier of Ukraine's 57th motorised brigade smokes near self-propelled artillery howitzer "Gvozdika" on the front line in the Kharkiv region, Ukraine, on Nov. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky, File)

FILE - Newly recruited soldiers toss their hats as they celebrate the end of their training at a military base close to Kyiv, Ukraine, on Sept. 25, 2023. (AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky, File)

FILE - A man rides a bicycle past the tombs of Ukrainian soldiers killed during the war, at Lisove cemetery in Kyiv, Ukraine, on April 23, 2024. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco, File)

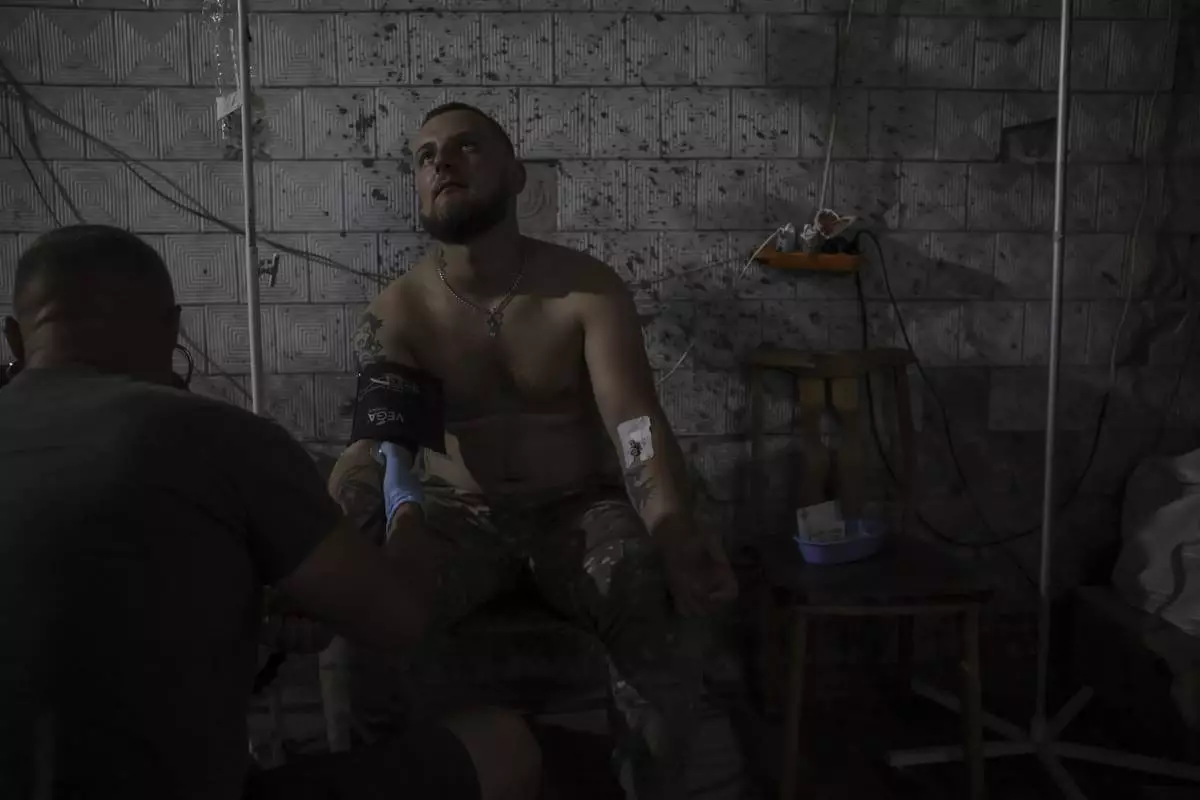

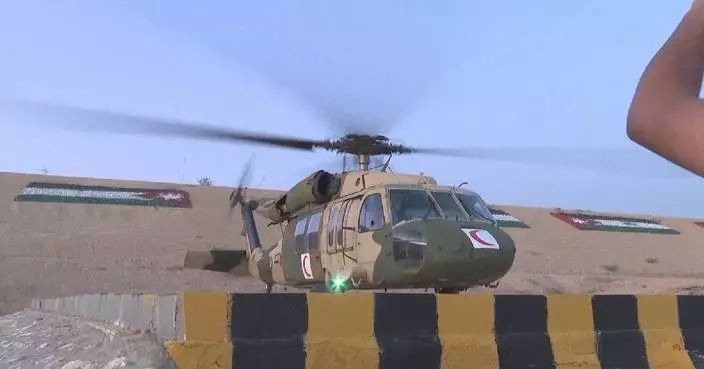

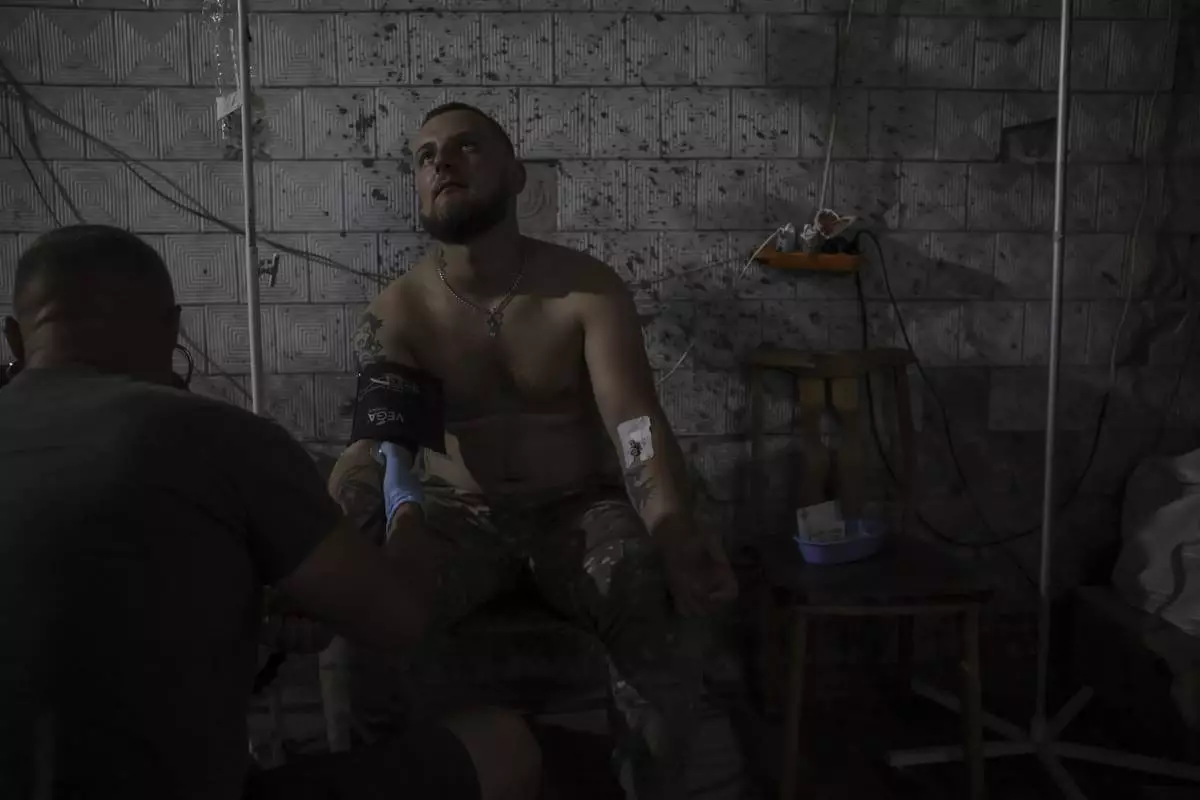

FILE - In this photo taken on July 9, 2024 and provided by Ukraine's 24th Mechanised Brigade press service, a military medics give first aid to a wounded Ukrainian soldier at a medical stabilisation point near Chasiv Yar, Donetsk region, Ukraine, on July 9, 2024, (Oleg Petrasiuk/Ukraine's 24th Mechanised Brigade via AP, File)

FILE - Military medics give first aid to wounded Ukrainian soldiers near Bakhmut, Ukraine, on Jan. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky, File)

FILE - Ukraine's Khartia brigade officer, who goes by callsign Kit, left, sits while his soldiers pilot drones in a shelter on the frontline near Kharkiv, Ukraine, on Nov. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky, File)

FILE - A shell-shocked Ukrainian soldier of the Azov brigade sits at the stabilization point after arriving from the front line, near Toretsk, Donetsk region, Ukraine, on Sept. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Evgeniy Maloletka, File)

FILE - Ukrainian soldiers carry shells to fire at Russian positions on the front line, near the city of Bakhmut, in Ukraine's Donetsk region, on March 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Efrem Lukatsky, File)