It's been called the Italian "green gold rush." Mild, barely there marijuana dubbed "cannabis light" has put Italy on the international weed map, producing hundreds of stores that sell pot by the pouch and attention from investors banking the legalization of stronger stuff will follow.

The flourishing retail industry around cannabis light - weed so non-buzzy, it's essentially the decaf coffee of marijuana - surfaced as an unintended by-product of a law meant to restore Italy as a top producer of industrial hemp. Now, storefronts that peddle chemically ineffective hemp flowers in varieties such as "Chill Haus" and "Black Buddha" are getting blowback that some Italians fear will nip business in the bud.

Click to Gallery

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 photo a man walks by the entrance of a cannabis light store, in which writing reads "Legal" on the shop window, in Milan, Italy, Thursday, June 6, 2019. It’s been called Italy’s ‘’Green Gold Rush,’’ a flourishing business around light marijuana that has created 15,000 jobs and an estimated 150 million euros worth of annual revenues in under three years. But the budding sector is facing a political and judicial buzzkill. (AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 photo cannabis light plants are displayed at a cannabis light store in Milan, Italy. Interior Minister Matteo Salvini has been an outspoken opponent of the marijuana light businesses that sprouted up around the country after pioneering 2016 legislation that many saw as a step toward eventual marijuana liberalization. (AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 photo, a shop assistant holds a Kokedama moss ball cannabis light plant at a cannabis light store in Milan, Italy. It’s been called Italy’s ‘’Green Gold Rush,’’ a flourishing business around light marijuana that has created 15,000 jobs and an estimated 150 million euros worth of annual revenues in under three years. But the budding sector is facing a political and judicial buzzkill. (AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

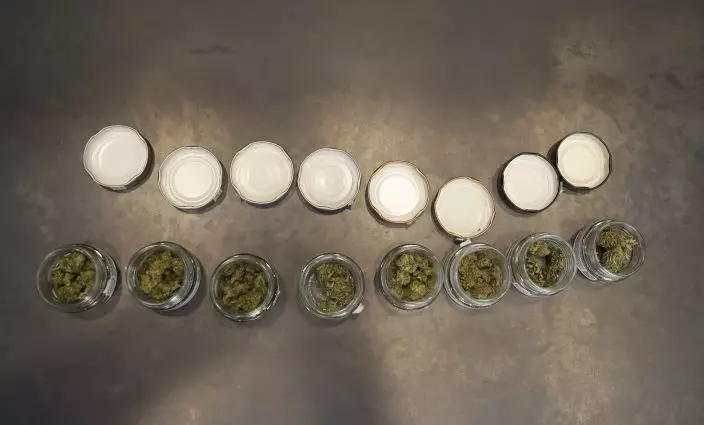

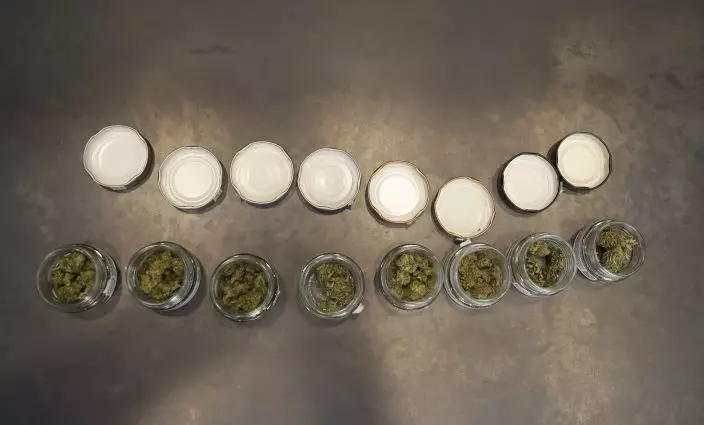

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 a shop assistant opens jars of cannabis buds at a cannabis light store in Milan, Italy. Interior Minister Matteo Salvini has been an outspoken opponent of the marijuana light businesses that sprouted up around the country after pioneering 2016 legislation that many saw as a step toward eventual marijuana liberalization.(AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 photo, cannabis buds and products are displayed at a cannabis light store in Milan, Italy. Interior Minister Matteo Salvini has been an outspoken opponent of the marijuana light businesses that sprouted up around the country after pioneering 2016 legislation that many saw as a step toward eventual marijuana liberalization. (AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 cannabis buds under a glass bell are displayed at a cannabis light store in Milan, Italy. Interior Minister Matteo Salvini has been an outspoken opponent of the marijuana light businesses that sprouted up around the country after pioneering 2016 legislation that many saw as a step toward eventual marijuana liberalization.(AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 open jars of cannabis buds are displayed at a cannabis light store in Milan, Italy. Interior Minister Matteo Salvini has been an outspoken opponent of the marijuana light businesses that sprouted up around the country after pioneering 2016 legislation that many saw as a step toward eventual marijuana liberalization.(AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 photo, a shop assistant, left, shows products to a customer at a cannabis light store in Milan, Italy. It’s been called Italy’s ‘’Green Gold Rush,’’ a flourishing business around light marijuana that has created 15,000 jobs and an estimated 150 million euros worth of annual revenues in under three years. But the budding sector is facing a political and judicial buzzkill. (AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 photo shows a cannabis light store in Rome. It’s been called Italy’s ‘’Green Gold Rush,’’ a flourishing business around light marijuana that has created 15,000 jobs and an estimated 150 million euros worth of annual revenues in under three years. But the budding sector is facing a political and judicial buzzkill. (AP PhotoAndrew Medichini)

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 photo a man walks by the entrance of a cannabis light store, in which writing reads "Legal" on the shop window, in Milan, Italy, Thursday, June 6, 2019. It’s been called Italy’s ‘’Green Gold Rush,’’ a flourishing business around light marijuana that has created 15,000 jobs and an estimated 150 million euros worth of annual revenues in under three years. But the budding sector is facing a political and judicial buzzkill. (AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 photo, biscuits and other products are displayed at a Cannabis light store, in Rome. It’s been called Italy’s ‘’Green Gold Rush,’’ a flourishing business around light marijuana that has created 15,000 jobs and an estimated 150 million euros worth of annual revenues in under three years. But the budding sector is facing a political and judicial buzzkill. (AP PhotoAndrew Medichini)

Italy's highest court clouded the climate four weeks ago by ruling it was illegal to market hemp-derived products that weren't "in practice devoid" of the power to provide a perceptible high. Sporadic testing and customer reviews suggested cannabis light outlets sold weed that weak. The law-and-order interior minister nonetheless declared war on the shops with neon leaf logos last month, vowing to close them "street by street, shop by shop" nationwide.

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 photo cannabis light plants are displayed at a cannabis light store in Milan, Italy. Interior Minister Matteo Salvini has been an outspoken opponent of the marijuana light businesses that sprouted up around the country after pioneering 2016 legislation that many saw as a step toward eventual marijuana liberalization. (AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

"It is neither possible nor acceptable that in Italy there are 1,000 shops where there are drugs legally, in broad daylight. This is disgusting," Matteo Salvini, who made keeping migrants out of Italy his primary focus after taking office a year ago, said.

Some business owners are ready to fight back. The owner of Green Planet in the southern city of Caserta chained himself to the fence around his locked shop this month after a raid in which police seized 16 grams of cannabis light. Gioel Magini, the owner of a Cannabis Amsterdam Store franchise in Sanremo, proposed a class-action lawsuit to keep the shops open and their owners from losing money.

"I closed a pizzeria to open this store. Now, they want us to go bankrupt," Magini told Italian news agency ANSA. "It's as if to fight alcoholism, the sale of non-alcoholic beer is banned."

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 photo, a shop assistant holds a Kokedama moss ball cannabis light plant at a cannabis light store in Milan, Italy. It’s been called Italy’s ‘’Green Gold Rush,’’ a flourishing business around light marijuana that has created 15,000 jobs and an estimated 150 million euros worth of annual revenues in under three years. But the budding sector is facing a political and judicial buzzkill. (AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

The commotion reflects the lag in Europe's pro-marijuana movement compared to the recreational use frontiers of North America. The coffee shops in Amsterdam where tourists have gone since the late 1970s to purchase pot in public never took off outside the Netherlands. While more than 30 European countries have laws allowing medical marijuana in some form, patient advocates complain of high prices and inadequate supplies.

Enter "la cannabis light," the catchy name Italians have for cannabis sativa plant derivatives with low levels of THC, the psychoactive compound in marijuana that causes a high. Hemp and marijuana are the same plant, but scientists classify dry plants with no more than 0.3% THC as hemp. In the 28-country European Union, of which Italy is a member, the cutoff is 0.2%. A December 2016 Italian law, however, set a domestic ceiling three times higher than that to give hemp farmers leeway for natural variations resulting from cultivation, according to Stefano Masini, a spokesman for Italy's Coldiretti agriculture lobby.

Although 0.6% is just over the THC concentration required for hemp to become marijuana in a botanist's book, Italian regulators assumed it was too low to have a mind-altering effect and its related consumer appeal. Entrepreneurs in a country with a lackluster economy nonetheless saw an opportunity.

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 a shop assistant opens jars of cannabis buds at a cannabis light store in Milan, Italy. Interior Minister Matteo Salvini has been an outspoken opponent of the marijuana light businesses that sprouted up around the country after pioneering 2016 legislation that many saw as a step toward eventual marijuana liberalization.(AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

The hemp law that took effect 2 ½ years ago permitted sales of cosmetics and products made with hemp. Gift boutiques, corner markets and stand-alone grow shops soon stocked cannabis-infused pasta, olive oil and gelato, but also jars and bags of "light" buds. Since marijuana still was illegal, producers labeled the products as "collector's items" not intended for consumption.

Rolling papers and glass pipes storekeepers might display nearby advertised otherwise.

"To say it is for collectors doesn't mean a thing," Coldiretti's Masini said. "If you can sell something that can be eaten or inhaled, obviously the use is something different."

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 photo, cannabis buds and products are displayed at a cannabis light store in Milan, Italy. Interior Minister Matteo Salvini has been an outspoken opponent of the marijuana light businesses that sprouted up around the country after pioneering 2016 legislation that many saw as a step toward eventual marijuana liberalization. (AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

Even so, cannabis light is a far cry from the legal weed with THC levels of 5% to 35% that adults can buy for recreational use at licensed dispensaries in some parts of the U.S. A Seattle blogger accustomed to the high-octane marijuana in Washington state called Italy's cannabis light "faux weed" after sucking on a fat joint in Rome and feeling nothing. Other reviewers have described a slight relaxing effect.

THC content - or more precisely, how much it takes to get stoned - was considered by Italy's Supreme Court of Cassation in the May 30 decision that alarmed the cannabis light industry. The case involved two light cannabis shops in central Italy that police shut down on suspicion of drug trafficking. An investigating judge threw out charges against the owner. Similar cases had resulted in conflicting verdicts on whether the shops could operate legally.

The Supreme Court's preliminary ruling summed up the contradictions of cannabis light in half a page. The court said the 2016 hemp law and its upper THC limit did not apply to cannabis leaves, buds or other spin-offs from hemp plants. Selling them remained illegal in Italy "unless such products are in practice devoid of a doping effect."

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 cannabis buds under a glass bell are displayed at a cannabis light store in Milan, Italy. Interior Minister Matteo Salvini has been an outspoken opponent of the marijuana light businesses that sprouted up around the country after pioneering 2016 legislation that many saw as a step toward eventual marijuana liberalization.(AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

The next day, police performed a "precautionary seizure" of Green Planet and two other stores in Caserta to test if the cannabis light they were selling was a legal non-high or carried illegal high-giving capacity. Local magistrates let Green Planet reopen after two weeks, which included the several its owner spent outside chained to the gated door in protest. Results must come back from THC tests on his confiscated products before he can sell cannabis light again.

Police raids in other cities have cannabis producers and sellers worried. They are anxiously waiting to see if the Supreme Court's full opinion, due by July 30, clarifies if they have a green light to keep mining the gold rush until the novelty of cannabis light wears off or more liberal laws clear the way for heavier marijuana on store shelves.

In other parts of Europe, changing attitudes on marijuana planted across the Atlantic might find fertile ground.. The government that took over in Luxembourg in November was the first in Europe to legalize recreational marijuana. Switzerland, which is not an EU member, allows cannabis light with up to 1% THC to be sold like tobacco. In Spain, cannabis social clubs are sprouting up since drug laws prohibiting marijuana possession are rarely enforced against casual users.

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 open jars of cannabis buds are displayed at a cannabis light store in Milan, Italy. Interior Minister Matteo Salvini has been an outspoken opponent of the marijuana light businesses that sprouted up around the country after pioneering 2016 legislation that many saw as a step toward eventual marijuana liberalization.(AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

Legislative attempts to take the light out of Italian cannabis so far have stalled on strong objections from the right. One of the two populist parties running the government now - the 5-Star Movement - enraged its coalition partner - the League party led by cannabis light critic Salvini - with such an attempt last year. Claudio Miglio, a lawyer who specializes in drug-related cases, is optimistic the cannabis light market will be allowed to keep growing in the meantime.

"The hope is that the market, which is the strongest power of all, will finally stimulate the public opinion on marijuana as it's happening for light cannabis now," Miglio said.

Lisa Leff contributed from London.

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 photo, a shop assistant, left, shows products to a customer at a cannabis light store in Milan, Italy. It’s been called Italy’s ‘’Green Gold Rush,’’ a flourishing business around light marijuana that has created 15,000 jobs and an estimated 150 million euros worth of annual revenues in under three years. But the budding sector is facing a political and judicial buzzkill. (AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 photo shows a cannabis light store in Rome. It’s been called Italy’s ‘’Green Gold Rush,’’ a flourishing business around light marijuana that has created 15,000 jobs and an estimated 150 million euros worth of annual revenues in under three years. But the budding sector is facing a political and judicial buzzkill. (AP PhotoAndrew Medichini)

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 photo a man walks by the entrance of a cannabis light store, in which writing reads "Legal" on the shop window, in Milan, Italy, Thursday, June 6, 2019. It’s been called Italy’s ‘’Green Gold Rush,’’ a flourishing business around light marijuana that has created 15,000 jobs and an estimated 150 million euros worth of annual revenues in under three years. But the budding sector is facing a political and judicial buzzkill. (AP PhotoLuca Bruno)

In this Thursday, June 6, 2019 photo, biscuits and other products are displayed at a Cannabis light store, in Rome. It’s been called Italy’s ‘’Green Gold Rush,’’ a flourishing business around light marijuana that has created 15,000 jobs and an estimated 150 million euros worth of annual revenues in under three years. But the budding sector is facing a political and judicial buzzkill. (AP PhotoAndrew Medichini)

BRUSSELS (AP) — In the year after Russia launched outright war on Ukraine, NATO leaders approved a set of military plans designed to repel an invasion of Europe. It was the biggest shake-up of the alliance’s defense readiness preparations since the Cold War.

The secret plans set out how Western allies would defend NATO territory from the Atlantic to the Arctic, through the Baltic region and Central Europe, down to the Mediterranean Sea. Up to 300,000 troops would move to its eastern flank within 30 days, many of them American. That would climb to 800,000 within six months.

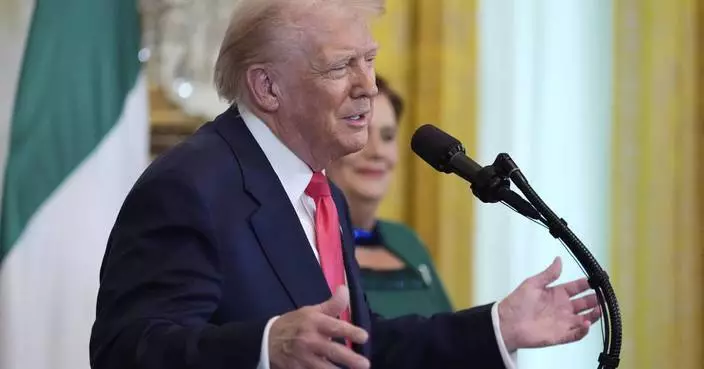

But the Trump administration warned last month that U.S. priorities lie elsewhere. Europe must take care of its own security, and those goals now seem questionable. Mustering just 30,000 European troops to police any future peace in Ukraine is proving a challenge.

Billions of euros are being shifted to military budgets, but only slowly, and the Europeans are struggling to fire up production in their defense industries.

Beyond funding, tens of thousands more European citizens might have to complete military service, and time is of the essence. NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte has warned that Russian forces could be capable of launching an attack on European territory in 2030.

Concerned about Russia's intentions, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk wants to introduce large-scale military training for every adult male, and double the size of Poland's army to around 500,000 soldiers.

“If Ukraine loses the war or if it accepts the terms of peace, armistice or capitulation … then, without a doubt — and we can all agree on that — Poland will find itself in a much more difficult geopolitical situation,” Tusk warned lawmakers last week.

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute estimates that Europe, including the U.K., has almost 1.5 million active duty personnel. But many can't be deployed on a battlefield, and those who can are hard to use effectively without a centralized command system.

The number of Russian troops in Ukraine at the end of 2024 was estimated to be around 700,000.

NATO troops are controlled by a U.S. general, using American air transport and logistics.

Analysts say that in the event of a Russian attack, NATO’s top military officer would probably dispatch around 200,000 U.S. troops to Europe to build on the 100,000 U.S. military personnel already based there.

With the Americans out of the picture, “a realistic estimate may therefore be that an increase in European capacities equivalent to the fighting capacity of 300,000 U.S. troops is needed,” the Brussels-based Bruegel think tank estimates.

“Europe faces a choice: either increase troop numbers significantly by more than 300,000 to make up for the fragmented nature of national militaries, or find ways to rapidly enhance military coordination,” Bruegel said.

The question is how.

NATO is encouraging countries to build up personnel numbers, but the trans-Atlantic alliance isn't telling them how to do it. Maintaining public support for the armed forces and for Ukraine is too important to risk by dictating choices.

“The way they go about it is intensely political, so we wouldn’t prescribe any way of changing this — whether to go for conscription, elective conscription, bigger reserves,” a senior NATO official said on the condition of anonymity because he wasn't authorized to brief journalists unless he remained unnamed.

“We do stress the point that fighting with those regional plans means that we are in collective defense and likely in an attrition war that requires way more manpower than we currently have, or we designed our force models to deliver,” he added.

Eleven European countries have compulsory military service: Austria, Cyprus, Croatia, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Sweden, and non-European Union nation Norway. The length of service ranges from as little as two months in Croatia to 19 months in Norway.

Poland isn't considering a return to universal military service, but rather a reserve system based on the model in Switzerland, where every man is obliged to serve in the armed forces or an alternative civilian service. Women can volunteer.

Belgium’s new defense minister plans to write a letter in November to around 120,000 citizens who are age 18 to try to persuade at least 500 of them to sign up for voluntary military service. Debate about the issue goes on in the U.K. and Germany.

Germany’s professional armed forces had 181,174 active service personnel at the end of last year — slightly lower than in 2023, according to a parliamentary report released Tuesday. That means it’s no closer to reaching a Defense Ministry target of 203,000 by 2031.

Last year, 20,290 people started serving in the German military, or Bundeswehr, an 8% increase, the report said. But of the 18,810 who joined in 2023, more than a quarter — 5,100 or 27% of the total — left again, most at their own request during the six-month trial period.

The German parliament’s commissioner for the armed forces, Eva Högl, said that army life is a hard sell.

“The biggest problem is boredom,” Högl said. “If young people have nothing to do, if there isn’t enough equipment and there aren’t enough trainers, if the rooms aren’t reasonably clean and orderly, that deters people and it makes the Bundeswehr unattractive.”

At the other end of the scale, tiny Luxembourg has unique demographic challenges. Of its roughly 630,000 passport holders, only 315,000 are Luxembourgers. The number of people of military service age — 18 to 40 — is smaller still.

Around 1,000 people are enlisted. That’s small compared to some European powers, but bigger per capita than the U.K. armed forces. Recently, Luxembourg — where unemployment is low and salaries are high — has struggled to find just 200-300 military personnel.

Military service comes with many challenges too, not least convincing someone to sign up when they might be sent to the front, and hastily trained conscripts can't replace a professional army. The draft also costs money. Extra staff, accommodation and trainers are needed throughout a conscript's term.

Geir Moulson contributed to this report from Berlin.

FILE - Army Forces of Croatia walk during the rehearsal of the French Bastille Day parade at the Champs-Elysees avenue in Paris, July 9, 2013. (AP Photo/Francois Mori, File)

FILE - Members of the Greek army take part in the military parade at the northern port city of Thessaloniki, Greece, Oct. 28, 2022. (AP Photo/Giannis Papanikos, File)

FILE - Members of La Legion, an elite unit of the Spanish Army, march to celebrate 'Dia de la Hispanidad' or Hispanic Day, in Madrid, Spain, Oct. 12, 2024. (AP Photo/Manu Fernandez, File)

FILE - Lithuanian Army soldiers take part in a Lithuanian-Polish Brave Griffin 24/II military exercise near the Suwalki Gap near the Polish border at the Dirmiskes village, in Lithuania on April 26, 2024. (AP Photo/Mindaugas Kulbis, File)

FILE - Volunteers takes part in basic training with the Polish army in Nowogrod, Poland, on June 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Czarek Sokolowski, File)

FILE - German soldiers take part in the Lithuanian-German division-level international military exercise 'Grand Quadriga 2024' at a training range in Pabrade, north of the capital Vilnius, Lithuania on May 29, 2024. (AP Photo/Mindaugas Kulbis, File)

FILE - Soldiers from the Belgian Special Forces perform a mock medical evacuation during an European Defense Agency joint military training exercise at Florennes airbase in Rosse, Belgium on Nov. 30, 2016. (AP Photo/Virginia Mayo, File)

FILE - Italian Air Force Eurofighter Typhoon military fighter jets participate in NATO's Baltic Air Policing Mission operate in Lithuanian airspace, on Sept.12, 2023. (AP Photo/Mindaugas Kulbis, File)

FILE - Soldiers demonstrate operational technics for close combat in a training class at a military camp set up for the Paris Olympic games, July 19, 2024, Vincennes, just outside Paris, France. (AP Photo/David Goldman, File)

FILE - Soldiers from Belgium and Luxembourg line up as they prepare to board a military transport plane at Melsbroek Military Airport in Melsbroek, Belgium, July 4, 2023. (AP Photo/Virginia Mayo, File)