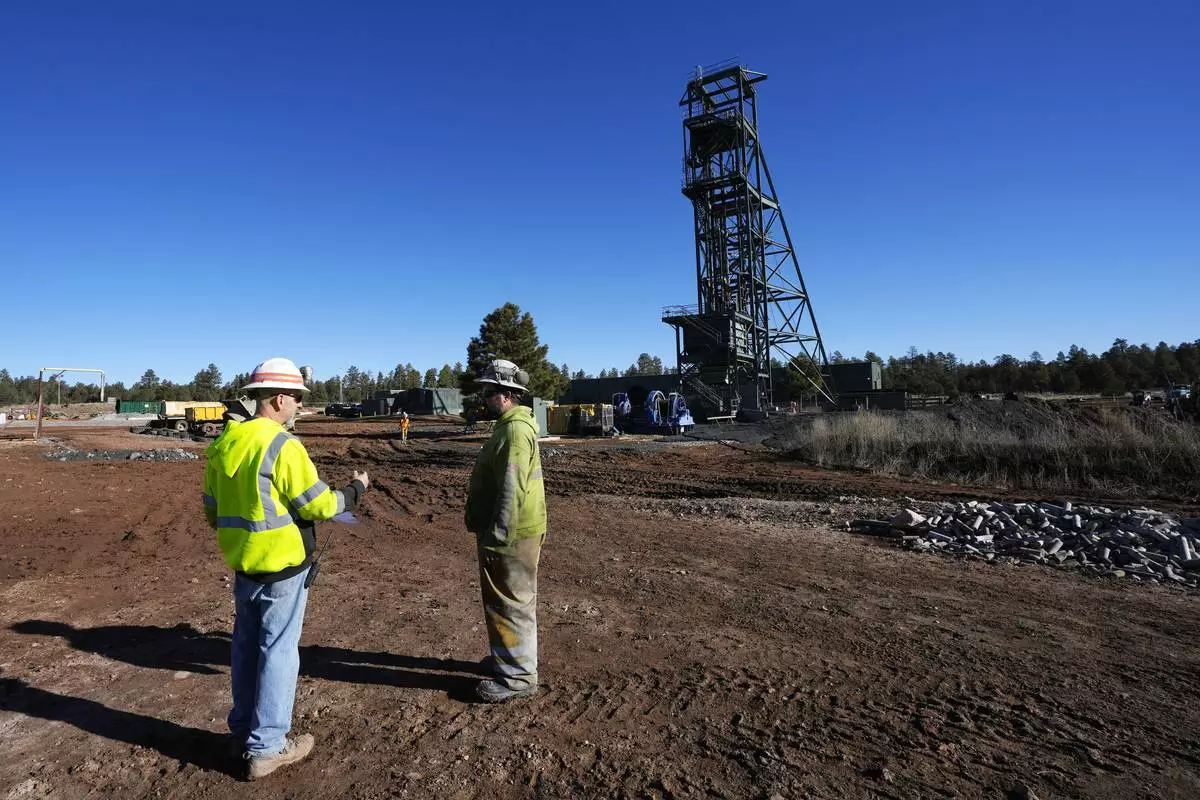

The largest uranium producer in the United States is ramping up work just south of Grand Canyon National Park on a long-contested project that largely has sat dormant since the 1980s.

The work is unfolding as global instability and growing demand drive uranium prices higher.

The Biden administration and dozens of other countries have pledged to triple the capacity of nuclear power worldwide in their battle against climate change, ensuring uranium will remain a key commodity for decades as the government offers incentives for developing the next generation of nuclear reactors and new policies take aim at Russia's influence over the supply chain.

But as the U.S. pursues its nuclear power potential, environmentalists and Native American leaders remain fearful of the consequences for communities near mining and milling sites in the West and are demanding better regulatory oversight.

Producers say uranium production today is different than decades ago when the country was racing to build up its nuclear arsenal. Those efforts during World War II and the Cold War left a legacy of death, disease and contamination on the Navajo Nation and in other communities across the country, making any new development of the ore a hard pill to swallow for many.

The new mining at Pinyon Plain Mine near the Grand Canyon's South Rim entrance is happening within the boundaries of the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukv National Monument that was designated in August by President Joe Biden. The work was allowed to move forward since Energy Fuels Inc. had valid existing rights.

Low impact with zero risk to groundwater is how Energy Fuels spokesman Curtis Moore describes the project.

The mine will cover only 17 acres (6.8 hectares) and will operate for three to six years, producing at least 2 million pounds (about 907,000 kilograms) of uranium — enough to power the state of Arizona for at least a year with carbon-free electricity, he said.

“As the global outlook for clean, carbon-free nuclear energy strengthens and the U.S. moves away from Russian uranium supply, the demand for domestically sourced uranium is growing,” Moore said.

Energy Fuels, which also is prepping two more mines in Colorado and Wyoming, has produced about two-thirds of the uranium in the U.S. in the last five years. In 2022, it was awarded a contract to sell $18.5 million in uranium concentrates to the U.S. government to help establish the nation’s strategic reserve for when supplies might be disrupted.

The ore extracted from the Pinyon Plain Mine will be transported to Energy Fuels’ mill in White Mesa, Utah — the only such mill in the U.S.

Amid the growing appetite for uranium, a coalition of Native Americans testified before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in late February, asking the panel to pressure the U.S. government to overhaul outdated mining laws and prevent further exploitation of marginalized communities.

Carletta Tilousi, who served for years on the Havasupai Tribal Council, said she and others have written countless letters to state and federal agencies and sat through hours of meetings with regulators and lawmakers. Her tribe's reservation lies in a gorge off the Grand Canyon.

“We have been diligently participating in consultation processes,” she said. “They hear our voices. There’s no response.”

A group of hydrology and geology professors and nuclear watchdogs sent Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs a letter in January, asking she reconsider permits granted by state environmental regulators that cleared the way for the mine. She has yet to respond and her office declined to answer questions from The Associated Press.

Lawyers for Energy Fuels said in a letter to state officials that reopening the permits would be an improper attempt to side step Arizona’s administrative procedures and rights protecting permit holders from “such politicized actions.”

The environmentalists' request followed a plea weeks earlier by the Havasupai saying mining at the foot of Red Butte will compromise one of the tribe's most sacred spots. Called Wii’i Gdwiisa by the Havasupai, the landmark is central to tribal creation stories and also holds significance for the Hopi, Navajo and Zuni people.

“It is with heavy hearts that we must acknowledge that our greatest fear has come true,” the Havasupai said in a January statement, reflecting on concerns that mining could affect water supplies, wildlife, plants and geology throughout the Colorado Plateau.

The Colorado River flowing through the Grand Canyon and its tributaries are vital to millions of people across the West. For the Havasupai Tribe, their water comes from aquifers deep below the mine.

The U.S. Geological Survey recently partnered with the Havasupai Tribe to examine contamination possibilities that could include exposure through inhalation and ingestion of traditional food and medicines, processing animal hides or absorption through materials collected for face and body painting.

Legal challenges aimed at stopping the Pinyon Plain Mine repeatedly have been rejected by the courts, and top officials in the Biden administration are reticent to weigh in beyond speaking generally about efforts to improve consultation with Native American tribes.

It marks another front in an ongoing battle over energy development and sacred lands, as tribes in Nevada and Arizona are fighting the federal government over the mining of lithium and the siting of renewable energy transmission lines.

The Pinyon Plain Mine, formerly known as the Canyon Mine, was permitted in 1984. Because it retained existing rights, the mine effectively became grandfathered into legal operation despite a 20-year moratorium placed on uranium mining in the Grand Canyon region by the Obama administration in 2012.

The U.S. Forest Service in 2012 reaffirmed an environmental impact statement that had been prepared for the mine years earlier, and state regulators signed off on air and aquifer protection permitting within the past two years.

“We work extremely hard to do our work at the highest standards," Moore said. “And it’s upsetting that we’re vilified like we are. The things we're doing are backed by science and the regulators.”

The regional aquifers feeding the springs at the bottom of the Grand Canyon are deep — around 1,000 feet (304 meters) below the mine — and separated by nearly impenetrable rock, Moore said.

State regulators also have said the geology of the area is expected to provide an element of natural protection against water from the site migrating toward the Grand Canyon.

Environmental reviews conducted as part of the permitting process have concluded the mine's operation won't affect visitors to the national park, area residents or groundwater or springs associated with the park. Still, environmentalists say the mine raises a bigger question about the Biden administration's willingness to adopt policies favorable of nuclear power.

The U.S. Commerce Department under the Trump administration issued a 2019 report describing domestic production as essential to national security, citing the need to maintain the nuclear arsenal and keep commercial nuclear reactors fueled to generate electricity. At that point, nuclear reactors supplied nearly 20% of the electricity consumed in the U.S.

The Biden administration is staying the course. It's in the midst of a multibillion-dollar modernization of the nation's nuclear defense capabilities, and the U.S. Energy Department on Wednesday offered a $1.5 billion loan to the owners of a Michigan power plant to restart the shuttered facility, which would mark a first in the U.S.

Taylor McKinnon, the Center for Biological Diversity's Southwest director, said pushing for more nuclear power and allowing mining near the Grand Canyon ”makes a mockery of the administration's environmental justice rhetoric."

“It’s literally a black eye for the Biden administration,” he said.

Using nuclear power to reach emissions goals is a hard sell in the western U.S. From the Navajo Nation to Ute Mountain Ute and Oglala Lakota homelands, tribal communities have deep-seated distrust of uranium companies and the federal government as abandoned mines and related contamination have yet to be cleaned up.

A complex of mines on the Navajo Nation recently was added to the federal Superfund list. The eastern edge of the reservation also is home to the largest radioactive accident in U.S. history. In 1979, more than 93 million gallons (350 million liters) of radioactive and acidic slurry spilled from a tailings disposal pond, contaminating water supplies, livestock and downstream communities. It was three times the radiation released at the Three Mile Island accident in Pennsylvania just three months earlier.

Teracita Keyanna with the Red Water Pond Road Community Association got choked up while testifying before the human rights commission in Washington, D.C., saying federal regulators proposed keeping contaminated soil onsite rather than removing it.

“It's really unfair that we have to deal with this and my children have to deal with this and later on, my grandchildren have to deal with this,” she said. “Why is the government just feeling like we're disposable. We're not.”

There is bipartisan backing in Congress for nuclear power, but some lawmakers who come from communities blighted by contamination are digging in their heels.

Congresswoman Cori Bush of Missouri said during a congressional meeting in January that lawmakers can't talk about expanding nuclear energy in the U.S. without first dealing with the effects that nuclear waste has had on minority communities. Bush pointed to her own district in St. Louis, where waste was left behind from the uranium refining required by the top-secret Manhattan Project.

“We have a responsibility to both fix — and learn from — our mistakes," she said, “before we risk subjecting any other communities to the same exposure.”

Montoya Bryan reported from Albuquerque, New Mexico. Associated Press writer Walter Berry in Phoenix contributed to this report.

The shaft tower at the Energy Fuels Inc. uranium Pinyon Plain Mine is shown Wednesday, Jan. 31, 2024, near Tusayan, Ariz. The largest uranium producer in the United States is ramping up work just south of Grand Canyon National Park on a long-contested project that largely has sat dormant since the 1980s. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

A worker sits in a mining winch operations room at the Energy Fuels Inc. uranium Pinyon Plain Mine Wednesday, Jan. 31, 2024, near Tusayan, Ariz. The largest uranium producer in the United States is ramping up work just south of Grand Canyon National Park on a long-contested project that largely has sat dormant since the 1980s. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

Workers talk at the Energy Fuels Inc. uranium Pinyon Plain Mine Wednesday, Jan. 31, 2024, near Tusayan, Ariz. The largest uranium producer in the United States is ramping up work just south of Grand Canyon National Park on a long-contested project that largely has sat dormant since the 1980s. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

Workers perform routine maintenance on a mining winch at the Energy Fuels Inc. uranium Pinyon Plain Mine Wednesday, Jan. 31, 2024, near Tusayan, Ariz. The largest uranium producer in the United States is ramping up work just south of Grand Canyon National Park on a long-contested project that largely has sat dormant since the 1980s. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

A woker checks on a piece of mining equipment at the Energy Fuels Inc. uranium Pinyon Plain Mine Wednesday, Jan. 31, 2024, near Tusayan, Ariz. The largest uranium producer in the United States is ramping up work just south of Grand Canyon National Park on a long-contested project that largely has sat dormant since the 1980s. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

Workers talk at the Energy Fuels Inc. uranium Pinyon Plain Mine Wednesday, Jan. 31, 2024, near Tusayan, Ariz. The largest uranium producer in the United States is ramping up work just south of Grand Canyon National Park on a long-contested project that largely has sat dormant since the 1980s. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

A uranium ore rock pile is the first to be mined at the Energy Fuels Inc. uranium Pinyon Plain Mine Wednesday, Jan. 31, 2024, near Tusayan, Ariz. The largest uranium producer in the United States is ramping up work just south of Grand Canyon National Park on a long-contested project that largely has sat dormant since the 1980s. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

A woker checks on a piece of mining equipment at the Energy Fuels Inc. uranium Pinyon Plain Mine Wednesday, Jan. 31, 2024, near Tusayan, Ariz. The largest uranium producer in the United States is ramping up work just south of Grand Canyon National Park on a long-contested project that largely has sat dormant since the 1980s. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

A pond at the Energy Fuels Inc. uranium Pinyon Plain Mine is shown on Wednesday, Jan. 31, 2024, near Tusayan, Ariz. The largest uranium producer in the United States is ramping up work just south of Grand Canyon National Park on a long-contested project that largely has sat dormant since the 1980s. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

The shaft tower at the Energy Fuels Inc. uranium Pinyon Plain Mine is shown Wednesday, Jan. 31, 2024, near Tusayan, Ariz. The largest uranium producer in the United States is ramping up work just south of Grand Canyon National Park on a long-contested project that largely has sat dormant since the 1980s. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)