Idaho librarian June Meissner was closing up for the day at the downtown Boise Public Library when a man approached her asking for help.

As an information services librarian, answering patrons' questions is part of Meissner’s day-to-day work, and serving the community is one of her favorite parts of the job.

Click to Gallery

Idaho librarian June Meissner was closing up for the day at the downtown Boise Public Library when a man approached her asking for help.

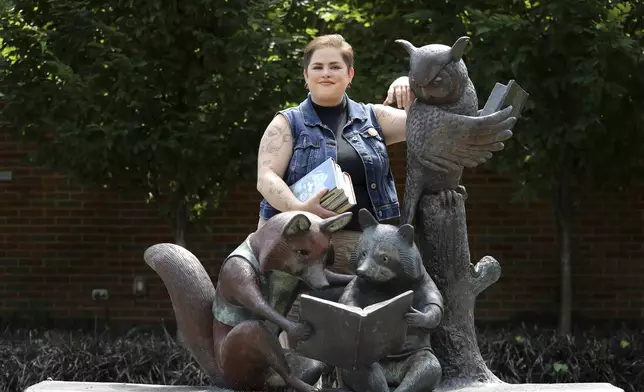

Chaz Carey poses for a photo at a library in Worthington, Ohio, Tuesday, June 11, 2024. Carey, a youth services librarian who is queer, knows firsthand how powerful books can be. Alison Bechdel's 2006 graphic memoir “Fun Home," in which the author comes to grips with her sexual orientation, changed Carey's life as a teenager. (AP Photo/Joe Maiorana)

June Meissner poses for a photo at the Boise Public Library in Boise, Idaho on Thursday, June 6, 2024. Meissner, a transgender woman and librarian, blocked a punch from a man yelling slurs while working at the library. (AP Photo/Kyle Green)

June Meissner poses for a photo at the Boise Public Library in Boise, Idaho on Thursday, June 6, 2024. Meissner, a transgender woman and librarian, blocked a punch from a man yelling slurs while working at the library. (AP Photo/Kyle Green)

June Meissner uses a computer at a workstation on the second floor of the Boise Public Library in Boise, Idaho on Thursday, June 6, 2024. Meissner, a transgender woman and librarian, blocked a punch from a man yelling slurs while working at the library. (AP Photo/Kyle Green)

June Meissner poses for a photo at the Boise Public Library in Boise, Idaho on Thursday, June 6, 2024. Meissner, a transgender woman and librarian, blocked a punch from a man yelling slurs while working at the library. (AP Photo/Kyle Green)

But when the man got close enough, “he took a swing at me and tried to punch me in the head,” said Meissner, a transgender woman. “I blocked it and he started yelling slurs and suggesting that he was going to come back and kill me.”

Worldwide Pride Month events are well underway to celebrate LGBTQ+ culture and rights. But it is coming at a time when people who identify as LGBTQ+ say they are facing increasing difficulties at work, ranging from being repeatedly misgendered to physically assaulted.

Gender nonconforming library workers in particular, like Meissner, are also grappling with growing calls for book bans across the U.S., with books about gender identity, sexual orientation and race topping the list of most criticized titles and making the attacks all the more personal.

“When we see attacks on those books, we have to understand that those are attacks on those kinds of people as well,” said Emily Drabinski, who is the president of the American Library Association and is gay. “To have my identity weaponized against libraries and library workers, the people and institutions I care about the most, has made it a difficult and painful year.”

The ALA said it documented the highest-ever number of titles targeted for censorship in 2023 in more than 20 years of tracking -- 4,240. That total surpassed 2022’s previous record by 65%, with Maia Kobabe’s coming-of-age story "Gender Queer" topping the list for most criticized library book for the third straight year.

Lawmakers are increasingly considering lawsuits, fines, and even imprisonment for distributing books some regard as inappropriate, including in Meissner’s home state of Idaho. Lawmakers there passed legislation that empowers local prosecutors to bring charges against public and school libraries if they don’t keep “harmful” materials away from children. The new law, signed by Idaho Gov. Brad Little in April, will go into effect on July 1.

“I do think that a lot of that political speech around it does make things more dangerous and worse for me,” Meissner said. “It is so much politicking and getting the general public riled up.”

Meissner’s own attacker was arrested and convicted, and she says that while the vast majority of her interactions at work are positive, she still struggles to let her guard down and is constantly assessing whether a situation could turn unsafe.

“As somebody who is working face to face with the public and trying to help people as much as possible, that really does get in the way,” she told The Associated Press, describing how she waits to make eye contact with a patron "and then, based on what I see when they look at me, that’ll tell me whether or not I should just be on edge, be wary.”

Florida-based conservative nonprofit Moms for Liberty, which describes itself as a parental rights organization and refers to its members as “joyful warriors,” has been at the forefront of a nationwide push to remove books that deal with race and gender identity.

But co-founder Tiffany Justice says the organization — which she says has more than 300 chapters in 48 states and more than 130,000 active members — is not anti-LGBTQ+, although Justice herself told the AP she thinks that the Q in the acronym, which stands for queer or questioning, “needs to go into the trash bin.” And according to the ALA's Office for Intellectual Freedom, about 38% of book challenges that “directly originated” from Moms for Liberty activity have LGBTQ+ themes.

Justice said Moms for Liberty challenges books like Gender Queer — a graphic novel about a young person’s struggle with gender identity that contains illustrations of sexual contact, masturbation and a sex toy — because they view the material as sexually explicit, not because they cover LGBTQ+ topics.

“The least interesting thing about a child should be their sexual orientation,” Justice said. “Why are we flooding them with sexual content?”

Despite the thousands of petitions to censor books about gender and sex, legal standards for deeming materials obscene or harmful to minors — and therefore not protected speech under the First Amendment — are very specific and high, and courts have historically sided with libraries, according to Vera Eidelman, a staff attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union who focuses on rights to free speech in the digital age.

“The mere fact that something is describing sex, describing nudity, even depicting those things, is not enough to make it qualify as obscenity," she said.

Regardless, the book banning movement has in many cases successfully restricted access to materials in which LGBTQ+ youth can see themselves depicted.

As of June 1, Louisiana libraries must allow parents or guardians to decide which books their child can check out. M’issa Fleming, a public librarian in New Orleans who uses they/them pronouns, says the new law could make it even more dangerous for queer and trans kids, who are already at higher risk of being victims of violence, substance use, and suicide than their straight, cisgender peers. And losing access to LGBTQ+ themed books may cause kids to turn to less reliable sources like Reddit.

“Public libraries could be offering as many ways as possible to make it less dangerous to learn about yourself, and the law just added another challenge,” Fleming said.

Chaz Carey, a children's librarian in Worthington, Ohio, knows firsthand how powerful books can be. Alison Bechdel's 2006 graphic memoir “Fun Home," in which the author comes to grips with her sexual orientation, changed Carey's life as a teenager.

“I felt seen. It was like my whole body just let out a breath," said Carey, who is queer and uses they/them pronouns. “It is just so important that these books remain on shelves. They save lives.”

Carey says being a children's librarian is a dream job, but the rise in book challenges and anti-LGBTQ+ rhetoric takes a mental toll. They are frequently misgendered at work, including by some patrons who go out of their way to do so while airing their political beliefs.

“The political environment is just an extra kind of weight as we navigate our lives and our places in our community," said Carey, who chairs ALA's Rainbow Roundtable, which aims to serve the information needs of LGBTQ+ people.

For Carey, what helps is “taking some time to feel sad, but then choosing queer joy and pride.”

The Associated Press’ women in the workforce and state government coverage receives financial support from Pivotal Ventures. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Chaz Carey poses for a photo at a library in Worthington, Ohio, Tuesday, June 11, 2024. Carey, a youth services librarian who is queer, knows firsthand how powerful books can be. Alison Bechdel's 2006 graphic memoir “Fun Home," in which the author comes to grips with her sexual orientation, changed Carey's life as a teenager. (AP Photo/Joe Maiorana)

Chaz Carey poses for a photo at a library in Worthington, Ohio, Tuesday, June 11, 2024. Carey, a youth services librarian who is queer, knows firsthand how powerful books can be. Alison Bechdel's 2006 graphic memoir “Fun Home," in which the author comes to grips with her sexual orientation, changed Carey's life as a teenager. (AP Photo/Joe Maiorana)

June Meissner poses for a photo at the Boise Public Library in Boise, Idaho on Thursday, June 6, 2024. Meissner, a transgender woman and librarian, blocked a punch from a man yelling slurs while working at the library. (AP Photo/Kyle Green)

June Meissner poses for a photo at the Boise Public Library in Boise, Idaho on Thursday, June 6, 2024. Meissner, a transgender woman and librarian, blocked a punch from a man yelling slurs while working at the library. (AP Photo/Kyle Green)

June Meissner uses a computer at a workstation on the second floor of the Boise Public Library in Boise, Idaho on Thursday, June 6, 2024. Meissner, a transgender woman and librarian, blocked a punch from a man yelling slurs while working at the library. (AP Photo/Kyle Green)

June Meissner poses for a photo at the Boise Public Library in Boise, Idaho on Thursday, June 6, 2024. Meissner, a transgender woman and librarian, blocked a punch from a man yelling slurs while working at the library. (AP Photo/Kyle Green)

DORTMUND, Germany (AP) — Here’s a quiz question: What do the 2022 World Cup final, the 2021 African Cup of Nations final, the 2020 European Championship final and the 2016 Copa America final have in common?

Answer: They were all settled by a penalty shootout.

Like it or not, the shootout — that tense battle of wills over 12 yards (11 meters) — has increasingly become a huge part of soccer, an unavoidable feature of the knockout stage in the biggest competitions.

Added to the laws of the game in 1970, penalty shootouts have marred careers (Roberto Baggio has never gotten over his miss in the 1994 World Cup final), spawned pizza adverts (Gareth Southgate starred in one after his decisive failure from the spot at Euro 1996) and, in Lionel Messi’s case at the most recent World Cup, earned a win that definitively secures a player a place in the pantheon of soccer greats.

It’s why those who delve into the psychology and science of soccer are perplexed why this tiebreaker system has been — and continues to be — overlooked by many teams, especially in these data-driven times.

“There are so many things you can do to prepare your team for penalties, to train them for penalties, to help your players and team cope with the pressure of penalties,” says Geir Jordet, professor at the Norwegian School of Sport Sciences and author of the recently published book, “Pressure: Lessons from the Psychology of the Penalty Shootout.”

“You can do this as an individual, as a team, as a manager,” he said.

The theory that penalty shootouts are a “lottery” is well worn and oft-repeated, with recently departed Chelsea manager Mauricio Pochettino saying just that in December after winning a cup game.

Johan Cruyff, the late Dutch maestro, gave short shrift to the idea that teams can prepare for spot kicks.

“Taking penalties in training is useless,” he said in 2000. “The penalty is a unique skill outside of football.”

Cruyff subscribed to the philosophy that a player can never simulate the pressure of a penalty shootout — that initial wait in the center circle, that long walk to the penalty spot, those few seconds face-to-face with the goalkeeper — on the training field.

Just this year, France coach Didier Deschamps railed against an attempt by the French Football Federation to come up with an initiative to improve the team’s performance in shootouts. France lost in them in the last 16 at Euro 2020 and in the 2022 World Cup final against Argentina.

“I’m convinced — and my past as a player gives me this information — that it’s impossible,” Deschamps said, “to recreate a situation, on a psychological level, between training and a match.”

Jordet acknowledged that, but said it’s “absurd” to not try to simulate these pressure situations in training.

“There are studies showing that training with mild anxiety will prepare you and help you perform better under conditions of high anxiety,” he said, before looking at other professions and areas of work.

“If you look at military training — in peacetime, which is what we’re used to, should they train for war activities and the pressure and stress of being in a conflict, or should they just sit back and say we cannot simulate the pressure and the stress of being in an active firefight? That’s absurd. It’s the same case with pilots or if you look at surgeons or ER doctors.”

Jordet has looked specifically at penalty shootouts at the last World Cup and how coaches managed the two minutes they had with their players between extra time finishing and the shootout starting. He noted the winning teams, “without exception,” were those whose coaches took the shortest time giving their instructions.

In the final, Argentina coach Lionel Scaloni’s nomination process took 15 seconds, Jordet said, because his team was prepared.

“Deschamps,” Jordet added, “spent almost 20 seconds considering who should take the shot for each of his penalty takers, looking around, showing basically how little clarity he had about what to do. It was probably something his players would pick up on as well.”

EUROS HISTORY

There have been 22 shootouts at the Euros, including four in 1996 and 2020. Of the 232 shots taken in the shootouts, 178 were successful — a 76.7% success rate. That fits the data models which typically say the expected success of a penalty is 0.76 (that is, 76 out of 100 penalties would typically be scored).

GO FIRST OR SECOND?

So much for the widely held perception that the team going second in a shootout is at a disadvantage for being under extra pressure. The latest major study of penalties, covering men's competitions in European soccer over the last 11 years, showed the winning percentage of the team shooting first in penalty kicks was 48.83. Jordet said the advantage has “progressively and dramatically shrunk” compared to older research, some of which said there was around a 60% chance of the team going first winning.

TEAM ORDERS

That same study showed the first kick is scored in shootouts more often than any other (nearly 84%) and is typically delivered by the most reliable penalty taker. Messi and Kylian Mbappé took the first two kicks in the World Cup final shootout, for example. The likelihood of success by a team's second taker dips to as low as around 72%, the study says, while the fifth kicker of the team shooting second hasn't gotten to take a penalty in 43.26% of shootouts. Placing your best taker at No. 5 in the list is dangerous, then — just ask Cristiano Ronaldo, who never got to take a penalty when Portugal lost a shootout to Spain in the Euro 2012 semifinals, and Mohamed Salah, who was left stranded as his Egypt team lost the African Cup of Nations final in 2021.

TACTICS

Watch out for gamesmanship around shootouts or regular penalties. Opponents have been seen attempting to scuff the turf around the spot in hopes of causing the taker to slip. That has led on some occasions to players from the team awarded the penalty gathering around the spot to protect the turf. Another recent phenomenon is one player holding onto the ball near the spot when a penalty has been awarded and then passing it, at the last minute, to the teammate taking the kick. “It’s about making the individual act of shooting a penalty into a collective team performance,” Jordet said. There also have been numerous examples of back-up goalkeepers or outfield players being brought on as a substitute late in extra time because they have a better record in penalties than the regular starter. See Netherlands goalkeeper Tim Krul at the 2014 World Cup and Australia goalkeeper Andrew Redmayne in qualifying for the 2022 World Cup.

NEW TECHNIQUE

There’s a new dominant penalty technique — and it’s not for the faint-hearted. It involves the taker approaching the ball and waiting for the goalkeeper to make the first move. What invariably becomes a stutter-step routine has been called the “goalkeeper-dependent technique” by experts like Jordet. “It’s very sophisticated and hard to perform when the pressure’s truly on,” he said. “If you’re competent at executing this technique, this will effectively delete the risk factor of the goalkeeper going in the right direction and your odds suddenly going down.” Poland captain Robert Lewandowski has been using it since 2016 — and used it against France on Tuesday — and Harry Kane is a recent adopter.

PROVEN PEDIGREE

History suggests Germany might be the best penalty-taking team in Europe, having won all six of its shootouts since losing the European Championship’s first to Czechoslovakia in the 1976 final. Conversely, there’s England, which has had so many penalty heartaches down the years — not least in the last Euro final — in its 2-7 overall record. The Netherlands (2-6) hasn’t fared much better.

AP soccer: https://apnews.com/hub/soccer

FILE - Senegal's Sadio Mane, top left, and teammates celebrate after scoring the winning penalty at the end of the African Cup of Nations 2022 final soccer match between Senegal and Egypt at the Ahmadou Ahidjo stadium in Yaounde, Cameroon, Sunday, Feb. 6, 2022. The penalty shootout is a tense battle of wills over 12 yards (11 meters) that has increasingly become a huge part of soccer and an unavoidable feature of the knockout stage in the biggest competitions. (AP Photo/Themba Hadebe, File)

FILE -Egyptian players react after the African Cup of Nations 2022 final soccer match between Senegal and Egypt at the Ahmadou Ahidjo stadium in Yaounde, Cameroon, Sunday, Feb. 6, 2022. The penalty shootout is a tense battle of wills over 12 yards (11 meters) that has increasingly become a huge part of soccer and an unavoidable feature of the knockout stage in the biggest competitions. (AP Photo/Sunday Alamba, File)

England's Bukayo Saka, center, is comforted after he missed to score the last penalty during the penalty shootout of the Euro 2020 soccer championship final between England and Italy at Wembley stadium in London, Sunday, July 11, 2021. The penalty shootout is a tense battle of wills over 12 yards (11 meters) that has increasingly become a huge part of soccer and an unavoidable feature of the knockout stage in the biggest competitions. (AP Photo/Frank Augstein, Pool, File)

FILE -England's goalkeeper Jordan Pickford saves a penalty shot y Italy's Andrea Belotti during the penalty shootout during the Euro 2020 soccer final match between England and Italy at Wembley stadium in London, Sunday, July 11, 2021. The penalty shootout is a tense battle of wills over 12 yards (11 meters) that has increasingly become a huge part of soccer and an unavoidable feature of the knockout stage in the biggest competitions. (Andy Rain/Pool Photo via AP, File)

FILE - Argentinian players celebrate after winning penalty shootout during the World Cup final soccer match between Argentina and France at the Lusail Stadium in Lusail, Qatar, Sunday, Dec. 18, 2022. The penalty shootout is a tense battle of wills over 12 yards (11 meters) that has increasingly become a huge part of soccer and an unavoidable feature of the knockout stage in the biggest competitions. (AP Photo/Petr David Josek, File)

FILE - Argentina's head coach Lionel Scaloni motivates his players in extra time of the World Cup final soccer match between Argentina and France at the Lusail Stadium in Lusail, Qatar, Sunday, Dec. 18, 2022. The penalty shootout is a tense battle of wills over 12 yards (11 meters) that has increasingly become a huge part of soccer and an unavoidable feature of the knockout stage in the biggest competitions. (AP Photo/Thanassis Stavrakis, File)

FILE - France's head coach Didier Deschamps talks with players before the start of the extra time during the World Cup final soccer match between Argentina and France at the Lusail Stadium in Lusail, Qatar, Sunday, Dec. 18, 2022. The penalty shootout is a tense battle of wills over 12 yards (11 meters) that has increasingly become a huge part of soccer and an unavoidable feature of the knockout stage in the biggest competitions. (AP Photo/Hassan Ammar, File)

FILE - In this Sunday, June 26, 2016 photo, Argentina's Lionel Messi reacts to losing 4-2 to Chile in penalty kicks during the Copa America Centenario championship soccer match, in East Rutherford, N.J. The penalty shootout is a tense battle of wills over 12 yards (11 meters) that has increasingly become a huge part of soccer and an unavoidable feature of the knockout stage in the biggest competitions. (AP Photo/Julio Cortez, File)

FILE - Argentina's Lionel Messi misses his shot during penalty kicks in the Copa America Centenario championship soccer match, Sunday, June 26, 2016, in East Rutherford, N.J. Chile defeated Argentina 4-2- in penalty kicks. The penalty shootout is a tense battle of wills over 12 yards (11 meters) that has increasingly become a huge part of soccer and an unavoidable feature of the knockout stage in the biggest competitions. (AP Photo/Julio Cortez, File)

FILE -Poland's Robert Lewandowski retakes his penalty kick to score during a Group D match between the France and Poland at the Euro 2024 soccer tournament in Dortmund, Germany, Tuesday, June 25, 2024. The penalty shootout is a tense battle of wills over 12 yards (11 meters) that has increasingly become a huge part of soccer and an unavoidable feature of the knockout stage in the biggest competitions. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits, File)

FILE - Argentina's Gonzalo Montiel, right, scores the winning penalty during a shootout to win the World Cup final soccer match against France at the Lusail Stadium in Lusail, Qatar, Sunday, Dec. 18, 2022. The penalty shootout is a tense battle of wills over 12 yards (11 meters) that has increasingly become a huge part of soccer and an unavoidable feature of the knockout stage in the biggest competitions. (AP Photo/Francisco Seco, File)

FILE - England's Harry Kane left, shoots to score past Italy's goalkeeper Gianluigi Donnarumma during penalty shootout of the Euro 2020 soccer championship final match between England and Italy at Wembley Stadium in London, Sunday, July 11, 2021. The penalty shootout is a tense battle of wills over 12 yards (11 meters) that has increasingly become a huge part of soccer and an unavoidable feature of the knockout stage in the biggest competitions. (Paul Ellis/Pool via AP, File)