BOSTON (AP) — Jazz Chisholm Jr. made his New York Yankees debut Sunday night against the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park, one day after he was acquired from the Miami Marlins for three minor leaguers.

Chisholm arrived at the ballpark about 90 minutes before the first pitch and was penciled into the lineup batting fifth and playing center field. Wearing uniform No. 13, he went 1 for 5 with a single and scored a late run in the Yankees' 8-2 victory.

“I was super excited,” Chisholm said about putting on a Yankees uniform. “Every kid dreams of being a Yankee, it's the most famous team in baseball that Derek Jeter played on, if you know what I mean. Everybody's favorite player was Derek Jeter growing up. I had him as an owner, so I just feel it was right to come up and put on a uniform.”

Chisholm jumped right into the action after arriving later than he planned.

“The flight, we stayed in the air an extra hour, the drive over here we were in the car for an extra 30 minutes because of the traffic,'' he said. ”It was a lot of stops into getting here. I got here, put on the uniform and went out and played."

Chisholm said manager Aaron Boone called him Saturday and asked if playing right away would be too much.

“Right now, I’ve got him in the middle of the order,” Boone said about 40 minutes before Chisholm arrived. “I kind of see him there right now, especially the way (Alex Verdugo), I feel like, is starting to swing the bat.”

Asked how he decided on No. 13, Chisholm said: "There was no single digits available," referring to the the Yankees’ rich history with retired numbers.

Then he explained it was because Alex Rodriguez wore it.

“It was only right to find the number that I adored as a kid, watching A-Rod,” he said.

An All-Star second baseman in 2022, the 26-year-old Chisholm has played center field for most of the past two seasons. He batted .249 with 13 homers and 50 RBIs for Miami this year and is a .246 career hitter with 66 homers and 205 RBIs in five seasons.

Boone said Chisholm could also bat leadoff. He got his 23rd stolen base Sunday night, matching his career high.

“We’ll just see how it all shakes out,” Boone said. “The biggest thing with him getting in today, I wanted to get him starting to work in the dirt, in the infield, but I felt like just getting in, I’d put him in the outfield for today.”

Gleyber Torres is New York's everyday second baseman, though he can become a free agent after the World Series. Boone said if Chisholm plays the infield for the Yankees this year it will probably be at third base — a position he's never played in the majors.

“I want him to start working there. It’s not something he’s played, obviously. He came up as a shortstop. I feel like he has the skill set to do it,” Boone said. “I know he’s open to doing it, but I want to see how that looks. … Excited to have him. We’re a better team today, a better roster with him here.”

To open a spot for Chisholm, infielder J.D. Davis was designated for assignment. Davis went 2 for 19 (.105) with one RBI and nine strikeouts in seven games for New York after being acquired from Oakland on June 23.

Boone also said slugger Giancarlo Stanton remains on track to come off the injured list Monday in Philadelphia. Stanton hasn’t played since straining his left hamstring while running the bases on June 22.

AP MLB: https://apnews.com/hub/mlb

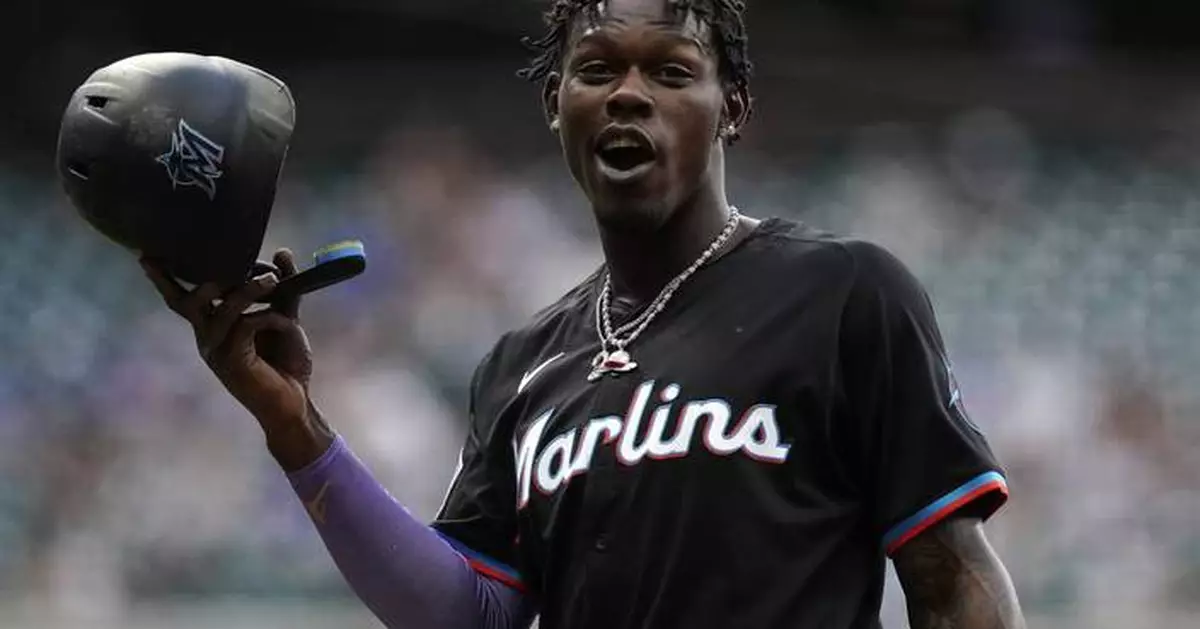

Miami Marlins' Jazz Chisholm Jr. walks from the field to the dugout during the seventh inning of a baseball game against the New York Mets, Monday, July 22, 2024, in Miami. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky)

Miami Marlins' Jazz Chisholm Jr. reacts during the second inning of a baseball game against the Milwaukee Brewers, Friday, July 26, 2024, in Milwaukee. (AP Photo/Aaron Gash)

SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — A South Korean commission found evidence that women were pressured into giving away their infants for foreign adoptions after giving birth at government-funded facilities where thousands of people were confined and enslaved from the 1960s to the 1980s.

The report by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission on Monday came years after The Associated Press revealed adoptions from the biggest facility for so-called vagrants, Brothers Home, which shipped children abroad as part of a huge, profit-seeking enterprise that exploited thousands of people trapped within the compound in the port city of Busan. Thousands of children and adults — many of them grabbed off the streets — were enslaved in such facilities and often raped, beaten or killed in the 1970s and 1980s.

The commission was launched in December 2020 to review human rights violations linked to the country’s past military governments. It had previously found the country’s past military governments responsible for atrocities committed at Brothers. Its latest report is focused on four similar facilities in the cities of Seoul and Daegu and the provinces of South Chungcheong and Gyeonggi. Like Brothers, these facilities were operated to accommodate government roundups aimed at beautifying the streets.

Ha Kum Chul, one of the commission’s investigators, said inmate records show at least 20 adoptions occurred from Daegu’s Huimangwon and South Chungcheong province’s Cheonseongwon in 1985 and 1986. South Korea sent more than 17,500 children abroad in those two years as its foreign adoption program peaked.

Ha said children taken from inmates at Huimangwon and Cheonseongwon were mostly newborns, who were transferred to two adoption agencies, Holt Children’s Services and Eastern Social Welfare Society, which placed them with families in the United States, Denmark, Norway and Australia. Most of the infants were transferred to the agencies on the day of their birth or the day after, Ha said, indicating that their adoptions were determined pre-birth.

While the facilities’ records say some of the women submitted memos expressing their consent to give away their children, other records indicate women were being pressured to do so, Ha said. A 1985 inmate record from Huimangwon flags a 42-year-old inmate with supposed mental health issues for “causing problems” by refusing to relinquish her child. Officials later note that she eventually did.

“It’s difficult to accurately determine how many more adopted children there might have been in other years,” Ha said, citing the commission’s limitations in staff. For Huimangwon, Ha said, the commission was only able to look through its inmate records from 1985 and 1986 and still found 14 adoptions. A further six adoptions were linked to inmates at Cheonseongwon.

At their peak, Huimangwon had about 1,400 inmates and Cheonseongwon 1,200. That was still smaller than the population at Brothers, which exceeded 3,000.

Holt and Eastern did not immediately respond to requests for comment on the commission’s findings.

Through documents obtained from officials, lawmakers or through public information requests, the AP in 2019 found direct evidence that 19 children were adopted out of Brothers between 1979 and 1986, and indirect evidence suggesting at least 51 more adoptions.

About 200,000 South Koreans were adopted to the United States, Europe and Australia in the past six decades, creating what’s believed to be the world’s largest diaspora of adoptees. Most of the adoptions occurred during the 1970s and ’80s, when South Korea’s then-military leaders were focused on economic growth and saw adoptions as a tool to reduce the number of mouths to feed, erase the “social problem” of unwed mothers and deepen ties with the democratic West.

The commission has also been conducting a separate investigation into the cases of 367 Korean adoptees in Europe, the United States and Australia, who suspect their biological origins were manipulated to facilitate their adoptions. It’s expected to release an interim report on that later this year.

The commission also identified other human rights problems at the four facilities it highlighted on Monday, which also included Gaengsaengwon in Seoul and Seonghyewon in Gyeonggi province. The facilities’ death tolls were high — the 262 inmates who were reported as dead from Gaengsaengwon in 1980 accounted for more than 25% of the facility’s population that year, Ha said.

Nearly 120 bodies of Cheonseongwon inmates were provided to a local medical school for anatomy practice from 1982 to 1992, the commission said. Most of the bodies were transferred to the school on the day the inmates were declared dead or the day after, and there are no indications that the facility made efforts to transfer the bodies to relatives, according to the commission, which didn't identify the school.

Huimangwon, Seonghyewon and Cheonseongwon also regularly received inmates transferred from Brothers, suggesting a “revolving-door” labor-sharing scheme between facilities that likely increased profit and prolonged the inmates’ confinements, the commission said.

The population at South Korea’s vagrant facilities peaked in the 1980s as the then-military government intensified roundups to beautify streets ahead of the 1986 Asian Games and the 1988 Olympic Games held in Seoul. South Korea transitioned to a democracy in the late 1980s and has long stopped its practice of grabbing homeless people, the disabled and children off the streets and confining them.

Brothers closed in 1988, months after a prosecutor exposed its horrors. Seonghyewon now runs welfare programs for homeless people in the city of Hwaseong, while the three other facilities have changed their names and the services they provide. None of those facilities immediately released comments following the commission's report.

“The four confinement facilities had been allowed to continue their operations without receiving any public investigations even after 1987,” when Brothers was exposed, said Lee Sang Hoon, one of the commission’s standing commissioners. “It’s significant that we have comprehensively revealed the details of the human rights violations at (other) vagrant facilities across the country that had been concealed for 37 years.”

Ha Kum Chul, one of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's investigators, speaks to the media during a news conference at the commission in Seoul, South Korea, Monday, Sept. 9, 2024. (Im Hwa-young/Yonhap via AP)

Lee Sang Hoon, a standing commissioner, speaks to the media during a news conference at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in Seoul, South Korea, Monday, Sept. 9, 2024. (Im Hwa-young/Yonhap via AP)