KAMPALA, Uganda (AP) — A former commander of the Lord’s Resistance Army rebel group has been convicted of dozens of crimes against humanity in a key moment of justice for many in Uganda who suffered decades of its brutal insurgency.

The long-awaited verdict in the trial of Thomas Kwoyelo was delivered Tuesday by a panel of the High Court that sat in Gulu, the northern city where the LRA once was active. It was the first atrocity case to be tried under a special division of the High Court that focuses on international crimes.

Kwoyelo faced charges including murder, pillaging, enslavement, imprisonment, rape and cruelty. He was convicted on 44 of the 78 counts he faced for crimes committed between 1992 and 2005.

It was not immediately clear when he would be sentenced.

Kwoyelo, whose trial began in 2019, had been in detention since 2009 as Ugandan authorities tried to figure out how to dispense justice in a way that was fair and credible. Human Rights Watch described his trial as “a rare opportunity for justice for victims of the two-decade war between” Ugandan troops and the LRA.

Prosecutors said Kwoyelo held the military rank of colonel within the LRA and that he ordered violent attacks on civilians, many of them displaced by the rebellion.

The LRA’s overall leader, Joseph Kony, is believed to be hiding in a vast area of ungoverned bush in central Africa. The U.S. has offered $5 million as a reward for information leading to the capture of Kony, who also is wanted by the International Criminal Court.

One of Kony’s lieutenants, Dominic Ongwen, was sentenced in 2021 by the ICC to 25 years of imprisonment for war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Thousands of other rebel combatants have received Ugandan government amnesty over the years, but Kwoyelo, who was captured in neighboring Congo, was denied such reprieve. Ugandan officials have never explained why. There were concerns by rights activists that the long delay in trying him violated his right to justice.

His trial was controversial, underscoring complex challenges in delivering justice in a society still healing from the consequences of war. As in Ongwen’s trial at the ICC, Kwoyelo asserted that he was abducted as a young boy to join the ranks of the LRA and that he could not be held responsible for the group’s crimes.

Kwoyelo, who denied the charges against him, testified that only Kony could answer for LRA crimes, and said everyone in the LRA faced death for disobeying the warlord.

The LRA, which began in Uganda as an anti-government rebellion, was accused of recruiting boys to fight and keeping girls as sex slaves. At the peak of its power, the group was a notoriously brutal outfit whose members for years eluded Ugandan forces in northern Uganda.

Some observers have pointed out that Ugandan military commanders cited in civilian abuses during the LRA insurgency have not faced justice.

The LRA was accused of committing multiple massacres targeting mostly members of the Acholi ethnic group. Kony, himself an Acholi, is a self-proclaimed messiah who said early in his rebellion that he wanted to rule Uganda according to the biblical Ten Commandments.

When military pressure forced the LRA out of Uganda in 2005, the rebels scattered across parts of central Africa. The group has faded in recent years, and reports of LRA attacks are rare.

Follow AP’s Africa coverage at: https://apnews.com/hub/africa

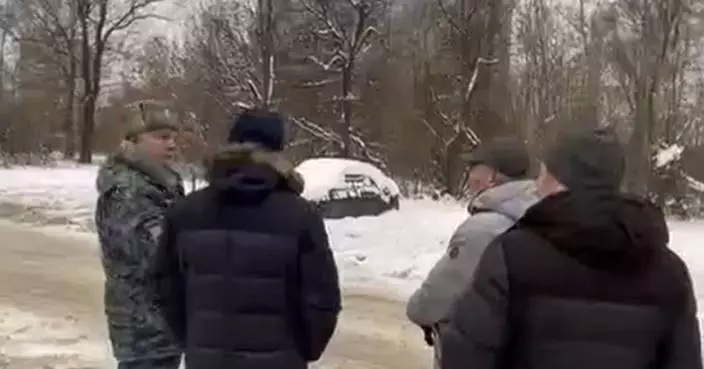

In this file photo taken Thursday, Feb. 12, 2015, a memorial marks the location of a mass burial site of those massacred in 2004 by the Lord's Resistance Army (LRA), at the Barlonyo displaced persons camp in northern Uganda. A former commander of the Lord’s Resistance Army rebel group has been convicted of dozens of crimes against humanity in a key moment of justice for many in Uganda who suffered decades of its brutal insurgency. The trial of Thomas Kwoyelo was the first atrocity case to be tried under a special division of Uganda's High Court that focuses on international crimes. (AP Photo/Rebecca Vassie, File)