PORTLAND, Ore. (AP) — Oregon elections officials said Monday they had struck over 1,200 people from the state's voter rolls after determining they did not provide proof of U.S. citizenship when they were registered to vote.

Of those found to be possibly ineligible, only nine people voted in elections since 2021, the Oregon secretary of state's office said. County clerks are working to confirm whether those people were indeed ineligible when they cast their ballots, or just hadn't provided the required documentation when they were registered to vote, said Molly Woon, the office's elections director.

The disclosures come amid heightened scrutiny of voter rolls nationwide, from Oregon to Arizona and Texas, as the presidential election nears. Citing an influx of immigrants in recent years at the U.S.-Mexico border, Republicans have raised concerns about the possibility that people who aren't citizens will be voting, even though state data indicates such cases are rare.

In Oregon, for example, the nine people whose citizenship hasn't been confirmed and who cast ballots represent a tiny fraction of the state's 3 million registered voters. Ten people were found to have voted after being improperly registered, but one was later confirmed to be eligible, authorities said.

The secretary of state’s office sent letters to the 1,259 people who were improperly registered to let them know their registration had been inactivated. They will not receive a ballot for the 2024 election unless they reregister with documents proving their citizenship. The state's deadline to register to vote is Oct. 15.

The mistake occurred in part because Oregon has allowed noncitizens to obtain driver’s licenses since 2019, and the state’s DMV automatically registers most people to vote when they obtain a license or ID. When DMV staff enter information in the computer system about someone applying for a driver's license or state ID, they can incorrectly choose an option in a drop-down menu that codes that person as having a U.S. passport or birth certificate when they actually provided a foreign passport or birth certificate, authorities said.

The DMV has taken steps to fix the issue, elections and transportation authorities said.

It has reordered the drop-down menu in alphabetical order so that a U.S. passport isn't the first default option. There will also be a prompt for U.S. passports asking DMV staff to confirm the document type. And if presented with a birth certificate, staff are now also required to enter the state and county of birth.

Additionally, office managers will now do a daily quality check to verify that the document entries match the document that was scanned, authorities said.

Gov. Tina Kotek on Monday called for the DMV to take further steps, such as providing updated training to staff and establishing a data quality control calendar in coordination with the secretary of state. She also called for a comprehensive report that outlines how the errors occurred, how they were corrected and how they will be prevented in the future.

Republican lawmakers in Oregon, who sent a letter to Kotek last week asking her to take steps to ensure the integrity of the state's voter lists, have called for a public hearing on the issue.

Secretary of State LaVonne Griffin-Valade said the election in November "will not be affected by this error in any way."

The issue has also gripped other states.

Last week, the Arizona Supreme Court unanimously ruled that nearly 98,000 voters whose citizenship documents hadn’t been confirmed can vote in state and local races. Most of them were voters who registered long ago and attested under the penalty of law that they are citizens. And in August, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a Republican push that could have blocked more than 41,000 Arizona voters from casting ballots in the closely contested swing state, but allowed some parts of a law to be enforced, requiring proof of citizenship.”

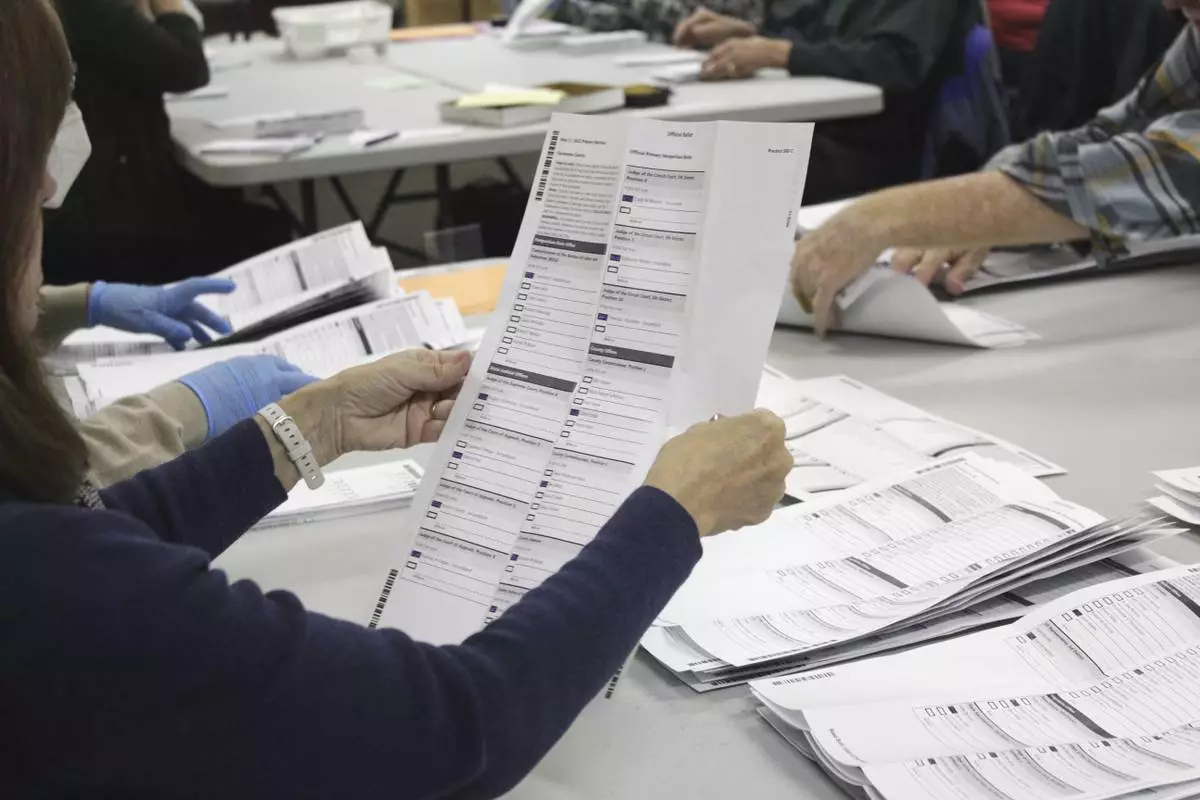

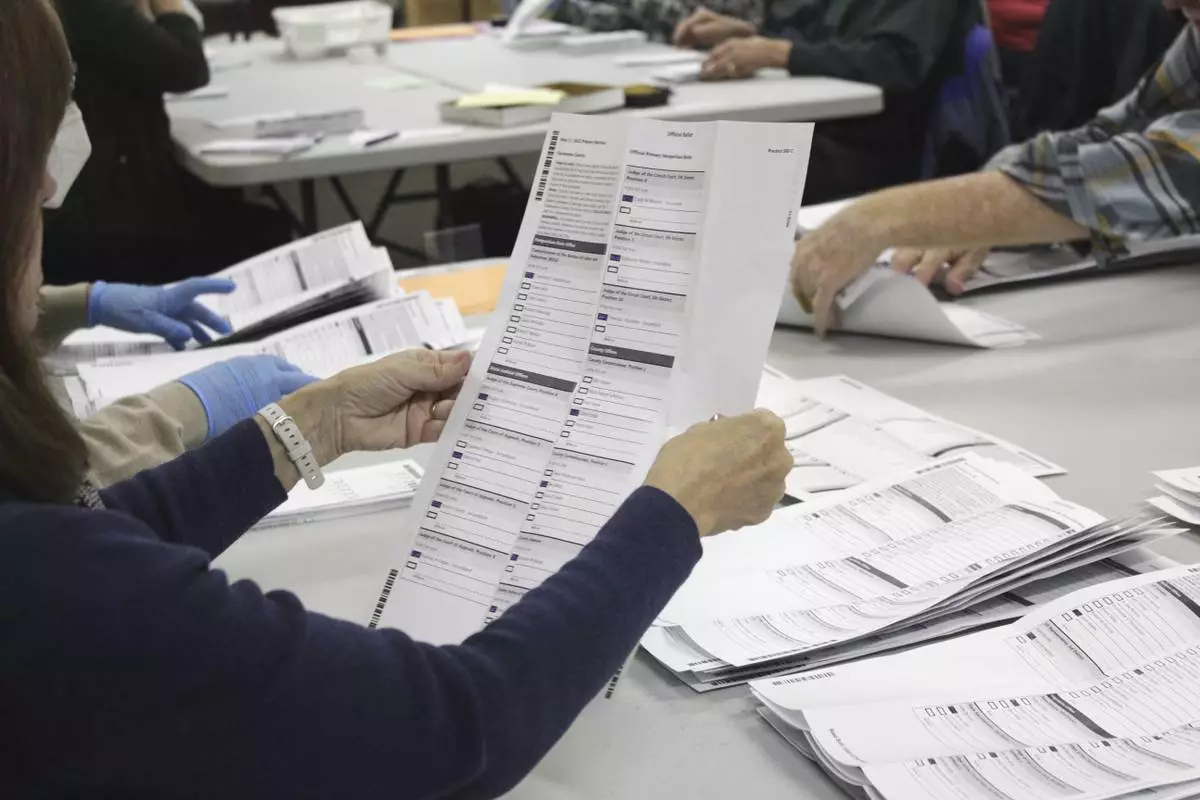

FILE— An election worker examines a ballot at the Clackamas County Elections office on May 19, 2022, Oregon City, Ore. (AP Photo/Gillian Flaccus, File)

NEW YORK (AP) — New York City Mayor Eric Adams says a family of Spanish tourists, including three children, died Thursday in a helicopter crash in the Hudson River that killed six people.

Adams said all of the dead have been recovered and removed from the water.

The helicopter broke apart in midair and crashed upside-down into the river between Manhattan and the New Jersey waterfront. It was the latest high-profile aviation disaster in the U.S., following other recent accidents in Washington and Philadelphia.

THIS IS A BREAKING NEWS UPDATE. AP’s earlier story follows below.

NEW YORK (AP) — A helicopter broke apart in midair and crashed upside-down into the Hudson River between Manhattan and the New Jersey waterfront Thursday, killing six people in the latest high-profile aviation disaster in the U.S., according to witnesses and a law enforcement official.

The New York Fire Department said it received a report of the crash at 3:17 p.m. All six people aboard were killed, a law enforcement official told The Associated Press. The official was not authorized to speak publicly and did so on condition of anonymity.

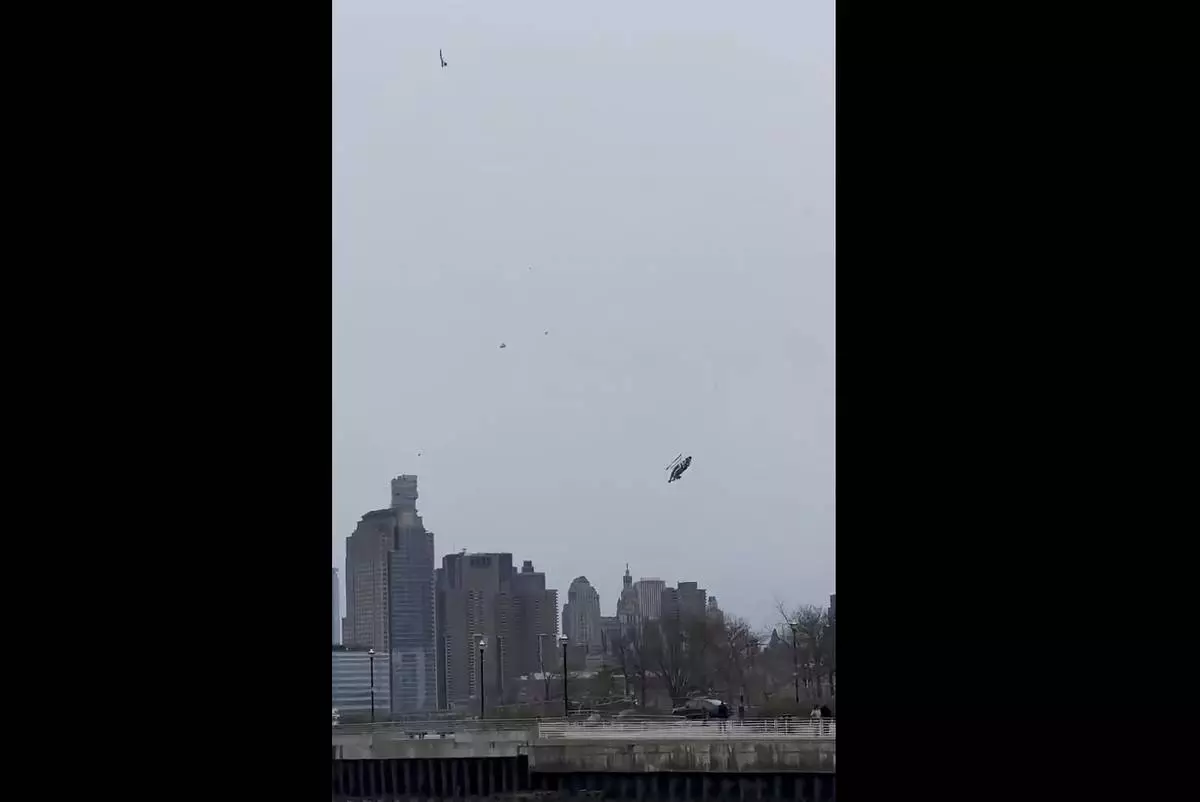

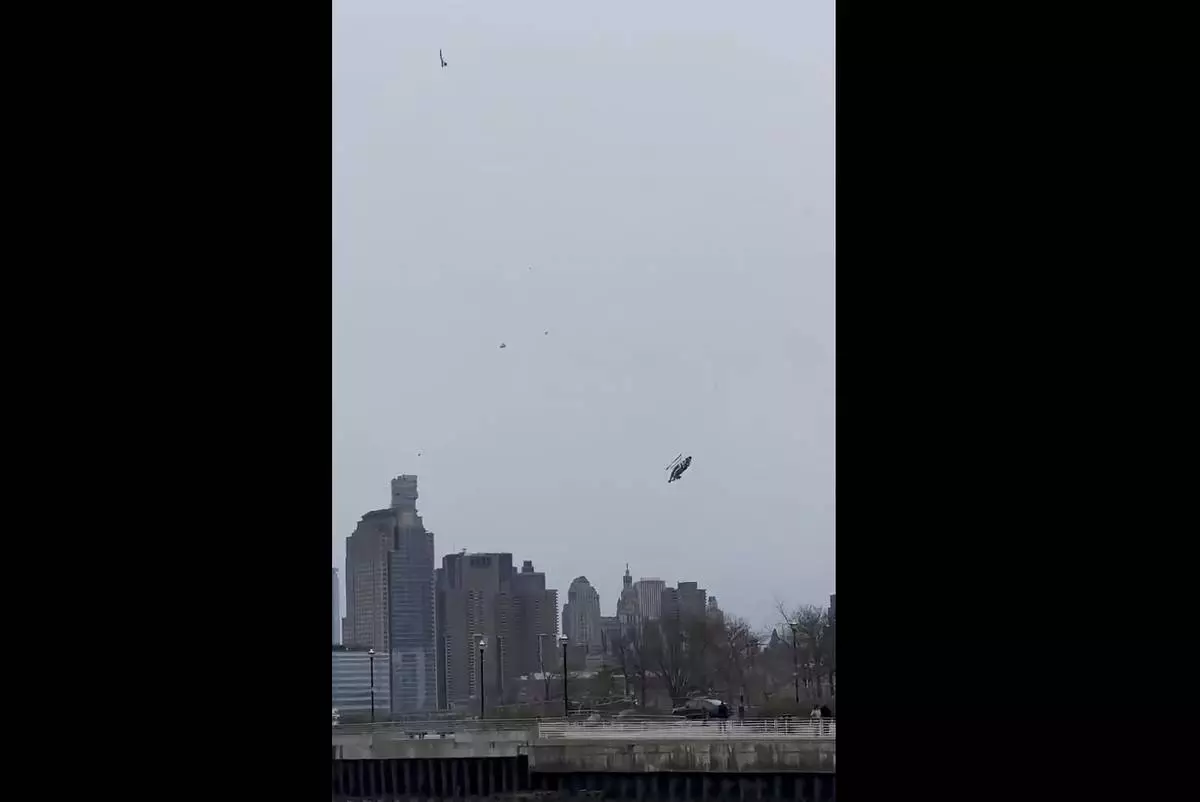

Witness Bruce Wall said he saw the helicopter “falling apart” in midair, with the tail and propeller coming off. The propeller was still spinning without the aircraft as it fell, he said.

Lesly Camacho, a hostess at a restaurant along the river in Hoboken, New Jersey, said she saw the helicopter spinning uncontrollably before it slammed into the water.

“There was a bunch of smoke coming out. It was spinning pretty fast, and it landed in the water really hard,” she said in a phone interview.

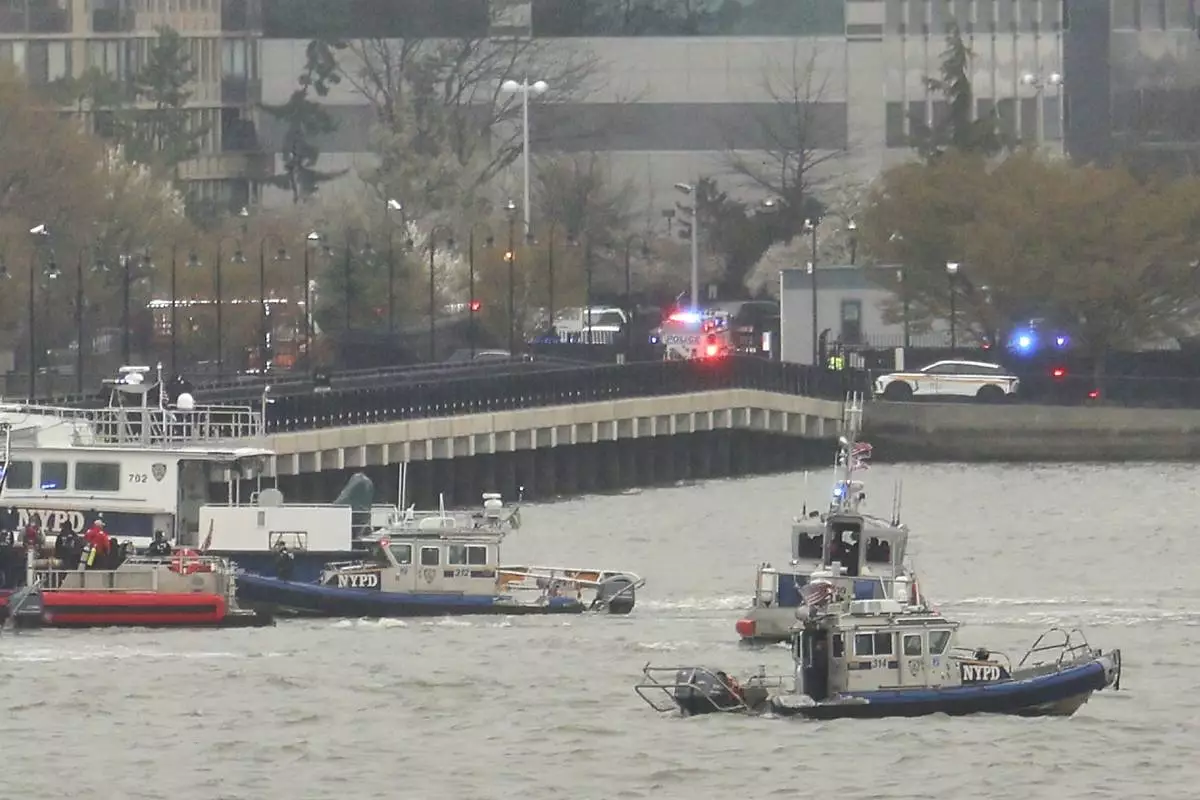

Video posted to social media showed parts of the chopper splashing into the water, and the overturned aircraft was submerged, with rescue boats circling it.

The skies were overcast at the time, but visibility over the river was not substantially impaired. Rescue crews had to deal with 45-degree water temperatures.

The Federal Aviation Administration identified the helicopter as a Bell 206, a model widely used in commercial and government aviation, including by sightseeing companies, TV news stations and police departments. It was initially developed for the U.S. Army before being adapted for other uses. Thousands have been manufactured over the years.

The National Transportation Safety Board said it would investigate.

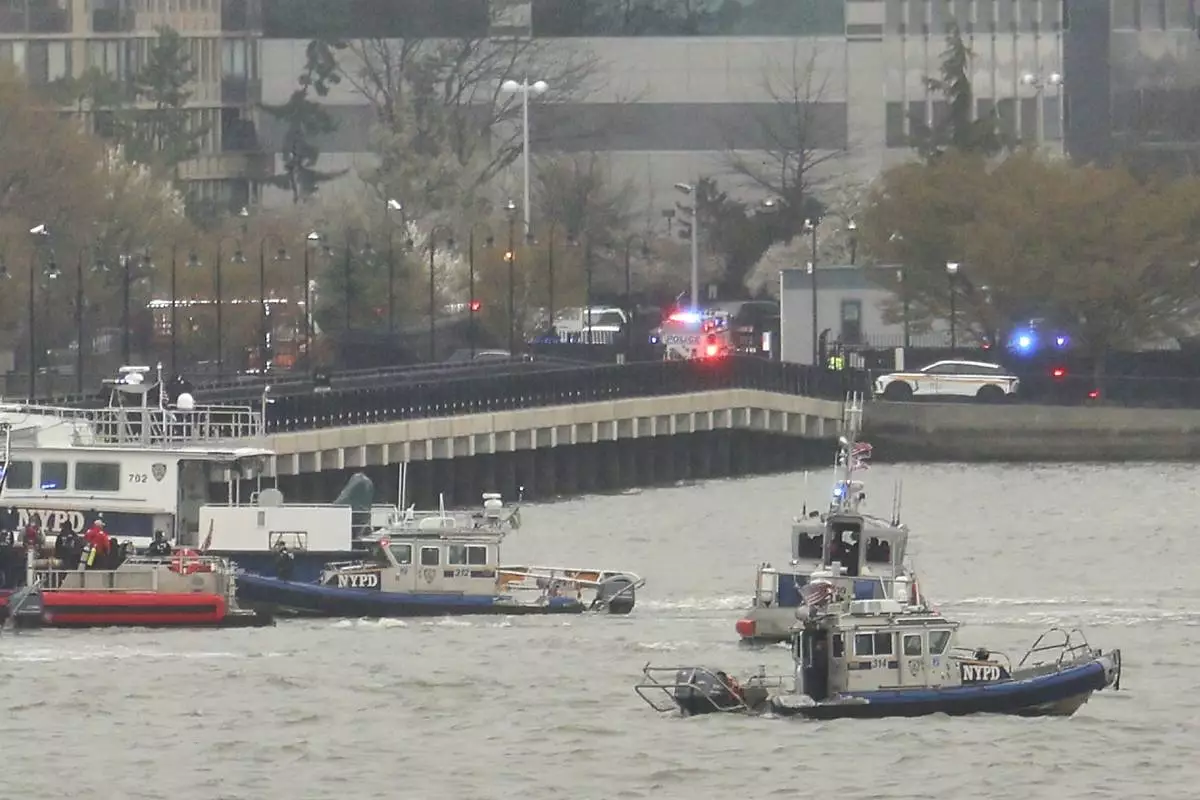

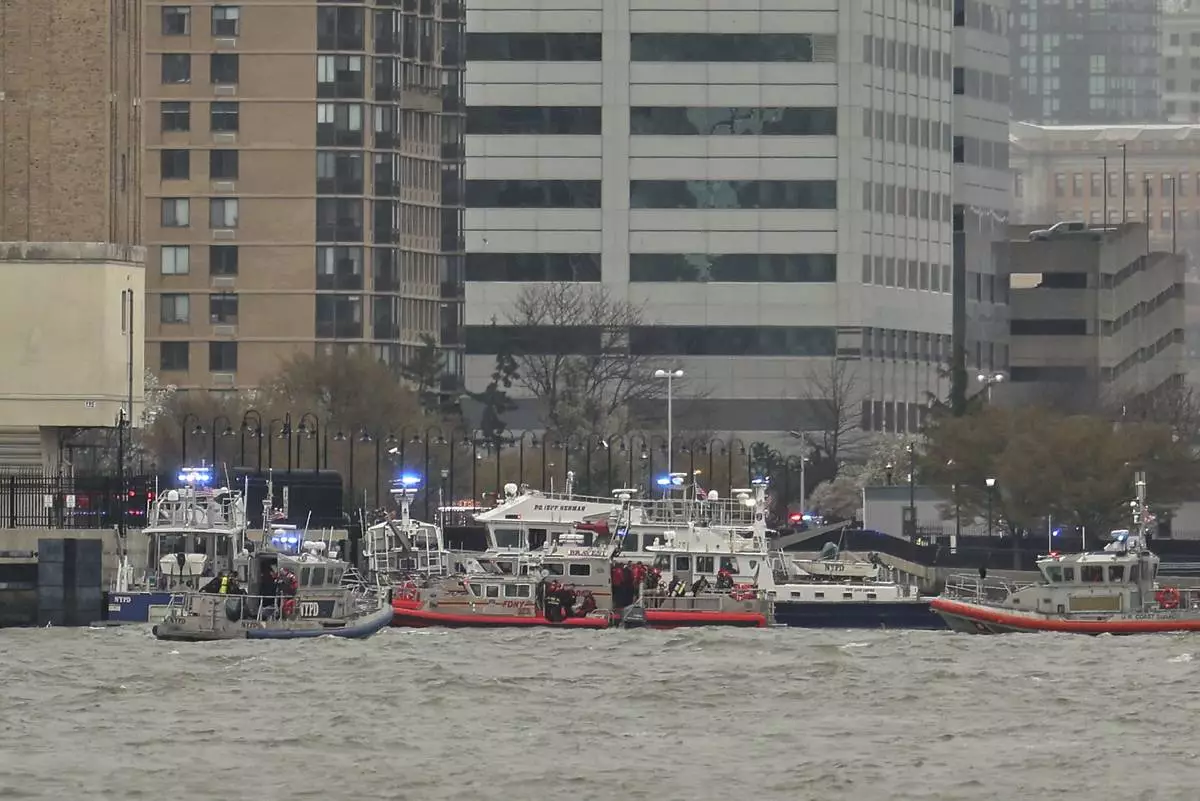

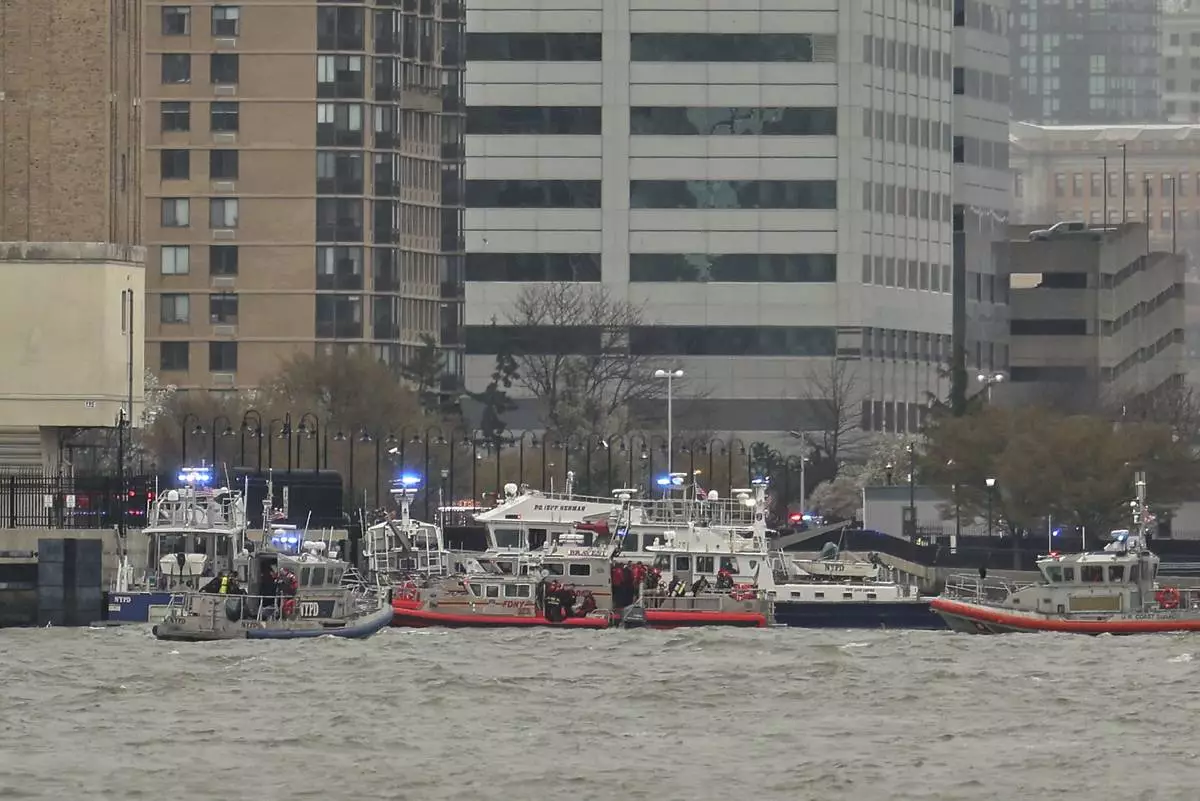

The rescue craft were near the end of a long maintenance pier for a ventilation tower serving the Holland Tunnel on the New Jersey side of the river. Fire trucks and other emergency vehicles were on nearby streets with their lights flashing.

The skies over Manhattan are routinely filled with planes and helicopters, both private recreational aircraft and commercial and tourist flights. Manhattan has several helipads that whisk business executives and others to destinations throughout the metropolitan area.

Over the years, there have been multiple crashes, including a collision between a plane and a tourist helicopter over the Hudson River in 2009 that killed nine people and the 2018 crash of a charter helicopter offering “open door” flights that went down into the East River, killing five people.

A medical transport plane killed seven people when it plummeted into a Philadelphia neighborhood in January. That happened two days after an American Airlines jet and an Army helicopter collided in midair in Washington — the deadliest U.S. air disaster in a generation.

The crashes and other close calls have left some people worried about the safety of flying.

First responders from New Jersey and New York respond to the scene where a helicopter crashed in the Hudson River, Thursday, April 10, 2025, in Jersey City, N.J. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

In this photo taken from video, a helicopter falls from the sky into the Hudson River , Thursday, April 10, 2025, in Jersey City, N.J. (Bruce Wall via AP)

A crane vessel arrives at the scene where a helicopter crashed into the Hudson River, Thursday, April 10, 2025, in Jersey City, N.J. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

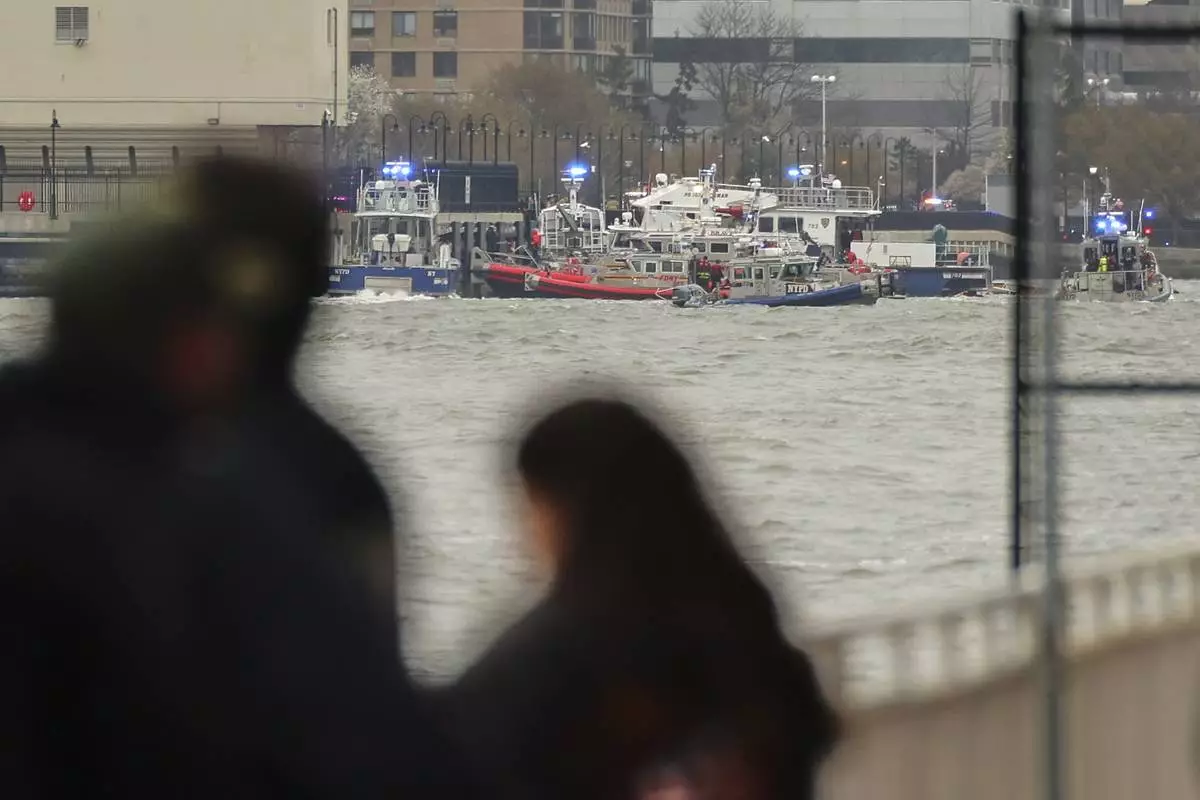

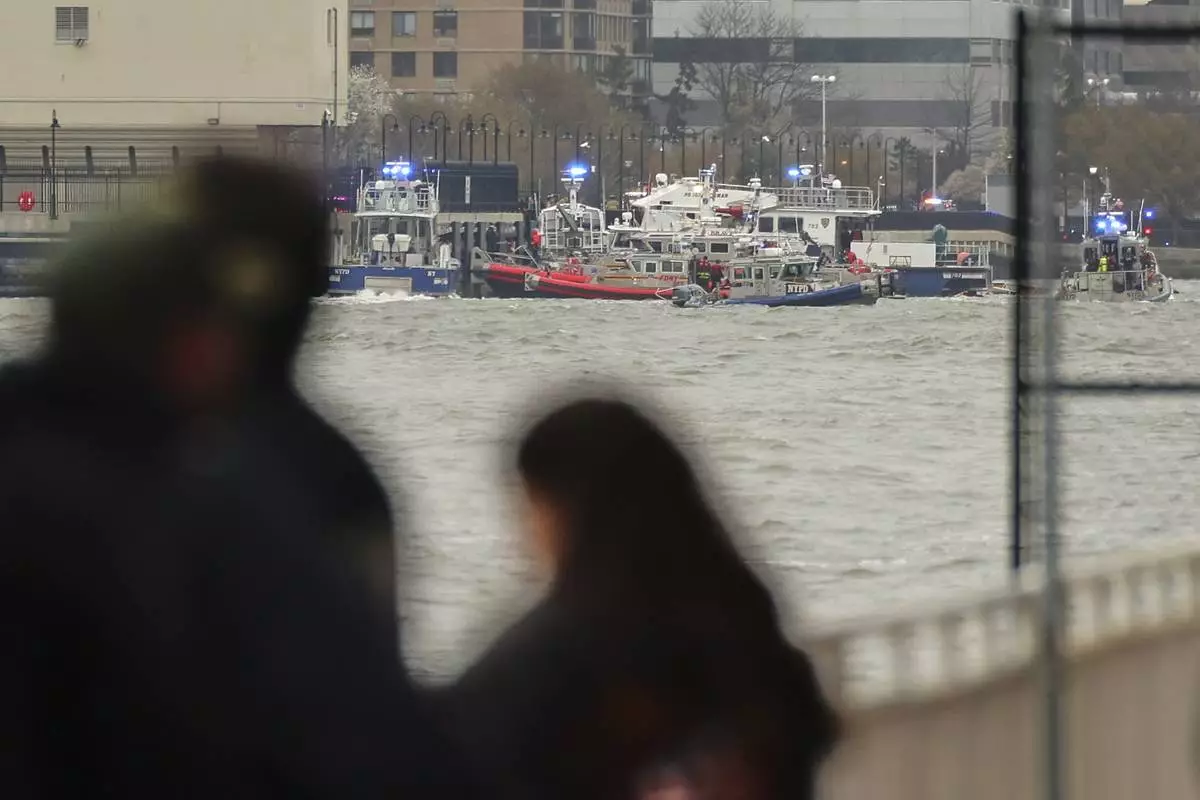

As seen from Pier 40 in New York, police and fire crews from New York and New Jersey respond to the scene where a helicopter crashed into the Hudson River, Thursday, April 10, 2025, in Jersey City, N.J. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

As seen from Pier 40 in New York, police and fire crews from New York and New Jersey respond to the scene Thursday, April 10, 2025, where a helicopter went down in the Hudson River between Manhattan and the New Jersey waterfront. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

As seen from Pier 40 in New York, police and fire crews from New York and New Jersey respond to the scene Thursday, April 10, 2025, where a helicopter went down in the Hudson River between Manhattan and the New Jersey waterfront. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

First responders from New Jersey and New York respond to the scene where a helicopter crashed in the Hudson River, Thursday, April 10, 2025, in Jersey City, N.J. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

As seen from Pier 40 in New York, police and fire crews from New York and New Jersey respond to the scene Thursday, April 10, 2025, where a helicopter went down in the Hudson River between Manhattan and the New Jersey waterfront. (AP Photo/Yuki Iwamura)

First responders walk along Pier 40, Thursday, April 10, 2025, in New York, across from where a helicopter went down in the Hudson River in Jersey City, N.J. (AP Photo/Jennifer Peltz)

A New York Fire Department Marine 1 boat departs from Pier 40, Thursday, April 10, 2025, in New York, across from where a helicopter went down in the Hudson River in Jersey City, N.J. (AP Photo/Jennifer Peltz)

First responders walk along Pier 40, Thursday, April 10, 2025, in New York, across from where a helicopter went down in the Hudson River in Jersey City, N.J. (AP Photo/Jennifer Peltz)