ASHEVILLE, N.C. (AP) — Before Hurricane Helene’s landfall last week, the National Weather Service began an all-out blitz to alert emergency planners, first responders and residents across the Southeast that the storm’s heavy rains and high winds could bring disaster hundreds of miles from the coast.

Warnings blared phrases such as “URGENT,” “life threatening” and “catastrophic” describing the impending perils as far inland as the mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee. Smartphones buzzed with repeated push alerts of flash floods and dangerous winds. States of emergency were declared from Florida to Virginia. And the weather service reached back to 1916 for a precedent, correctly predicting Helene would rank among the “most significant weather events” the Asheville, North Carolina, area had ever seen.

But the red flags and cataclysmic forecasts weren’t enough to prevent the still-rising death toll. The number has soared to at least 215 across six states. At least 72 of those were in hard-hit Asheville and surrounding Buncombe County from flash floods, mudslides, falling trees, crumbled roads and other calamities.

“Despite the dire, dire predictions, the impacts were probably even worse than we expected,” said Steve Wilkinson, the meteorologist in charge of the National Weather Service’s regional office in Greenville-Spartanburg, South Carolina.

“We reserve this strong language for only the worst situations,” he said. “But it’s hard to go out and tell people this is going to totally change the landscape of western North Carolina.”

As the region begins its long road to recovery, a task complicated by cut-off communities, a lack of running water and still-spotty cellphone service, the growing number of casualties has prompted soul-searching among devastated homeowners and officials alike. They wonder whether more could have been done to sound the alarms and respond in a mountainous region that’s not often in the path of hurricanes.

“It sounds stupid to say this, but I didn’t realize it would be like bombs going off,” Brenton Murrell said after surveying his Asheville neighborhood strewn with mud and debris, military Osprey aircraft whirring overhead. “It’s like a war zone.”

Like many residents interviewed by The Associated Press, Murrell had never experienced the effects of a hurricane and felt detached from the danger despite receiving numerous warnings of “extreme risk of loss of life and property.”

Murrell said those words never really scared him, in part because his neighbors had been talking for days about the last big flood two decades ago and offered mostly reassuring words that “if you’re not in a low-lying area, you’ll be fine.”

“There was some sort of disconnect,” said Murrell, who now regrets riding out the storm at home with his wife, two children and dog, even though they are all safe. “It’s human nature to not truly comprehend something until you’ve felt it yourself.”

Many residents said they had not grasped the magnitude of the storm until it was too late. For some, evacuating became impossible as fallen trees and surging floodwaters made roads and bridges impassable. The cascade of emergencies caught seemingly everyone off guard.

Sara Lavery, of Canton, said she received multiple alerts last Thursday before the worst of the storm had hit and was alarmed at how quickly “flood watches” on her phone progressed to “flood warnings.” Then she looked out at the Pigeon River near her home and got really scared.

“We saw a tree the size of telephone pole, a kitchen sink, a bedroom dresser,” she said. “It was terrifying.”

Still, she and her fiance decided to stay, partly because their home was on high ground, partly to leave the roads empty for others and help out endangered residents in lower areas.

“Some people don’t have a place to go, some don’t have a four-wheel vehicle to get out,” Lavery said. “People always say, ‘Why didn’t you evacuate?’ Not everyone can.”

“We never thought this would happen,” she said. “Western North Carolina is the mountains.”

As the storm swept through, Mia Taylor, of nearby Hendersonville, said she received alerts on her phone about the threat of floods “but some of us were kind of just like, ‘Oh, it’s not that serious.’”

She tried to drive to a nearby town to shelter with her children but found “every which way was blocked off.” She ended up turning around only for her car to shut off in the storm.

“You didn’t think that it was going to be this bad,” she said.

Lillian Govus, a Buncombe County spokesperson, said that has been a familiar refrain since the storm because no one alive in the area had seen anything approaching Helene’s destruction. She described the storm’s pre-dawn arrival last Friday as “insidious,” noting some residents were in bed and may not have heard the emergency alerts.

“Folks were trying to evacuate, but there was nowhere to go,” she said. “If there’s a landslide, it doesn’t matter how high you go.”

Wilkinson, the meteorologist, said forecasters knew many days before the storm that Helene would be catastrophic for western North Carolina and began notifying the emergency management community in briefings and presentations, focusing primarily on flooding and secondarily on wind. Surrounding mountain towns like Asheville, a city of some 95,000, were of particular concern because the communities were built in valleys.

An AP analysis of social media postings and cellphone alerts found more than a dozen were sent by Buncombe County and the National Weather Service on Wednesday and Thursday alone. And the language used to convey the threat from Helene — “extremely rare event,” “prepare for a life-threatening storm,” “Act Now!” — became increasingly dire as authorities urged people to seek higher ground and evacuate in some cases. The most alarming ones said the destruction could be the worst in a century, referencing the “Great Flood of 1916” in which 80 people were killed.

In one of its repeated postings on the social platform X, Wilkinson’s staff pleaded with residents to take its warnings “very seriously” and have multiple means of receiving alerts.

“We made an attempt based on previous events, to hit our warnings well ahead of time,” Wilkinson told the AP, “so the alerts went out before the high wind hit. They kind of kept coming.”

The weather service’s rainfall and wind speed predictions largely held up, Wilkinson said, with some areas receiving more than 1 foot (0.3 meters) of rain. Mount Mitchell State Park recorded wind gusts at 106 mph (171 kph). The French Broad River Basin saw rivers topping their highest-ever crests by several feet, the weather service reported, adding Helene brought “likely the most severe flooding in recorded history across Buncombe County.”

“The last time a storm like this hit was in the Book of Genesis when Noah had to build an ark,” said Zeb Smathers, the mayor of Canton, North Carolina.

Wilkinson said it might be impossible to know the number of people who didn’t heed the warnings or didn’t get them. Cellphone service is sometimes spotty in the mountainous region and may have gotten worse as the storm rolled in.

“I honestly believe we did everything we could have done,” he said. “It’s sad that we couldn’t do more, but we’re trying to recognize that what we did made some difference.”

In the aftermath of the storm, Wilkinson’s office posted an emotional letter on X thanking first responders and calling Helene “the worst event in our office’s history.”

“As meteorologists we always want to get the forecast right,” it said. “This is one we wanted to get wrong.”

Mustian and Condon reported from New York. Brittany Peterson in Hendersonville, North Carolina, and Christopher Keller in Albuquerque, New Mexico, contributed reporting.

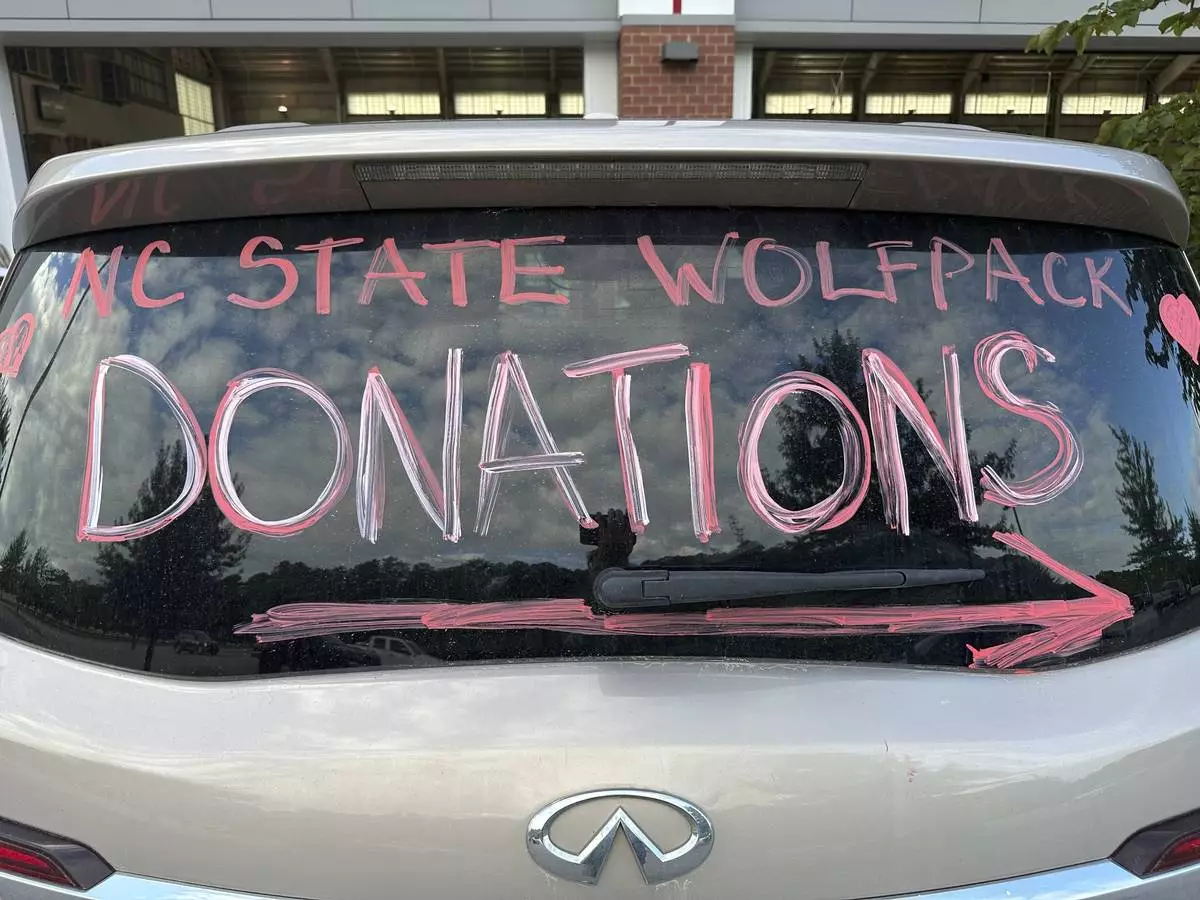

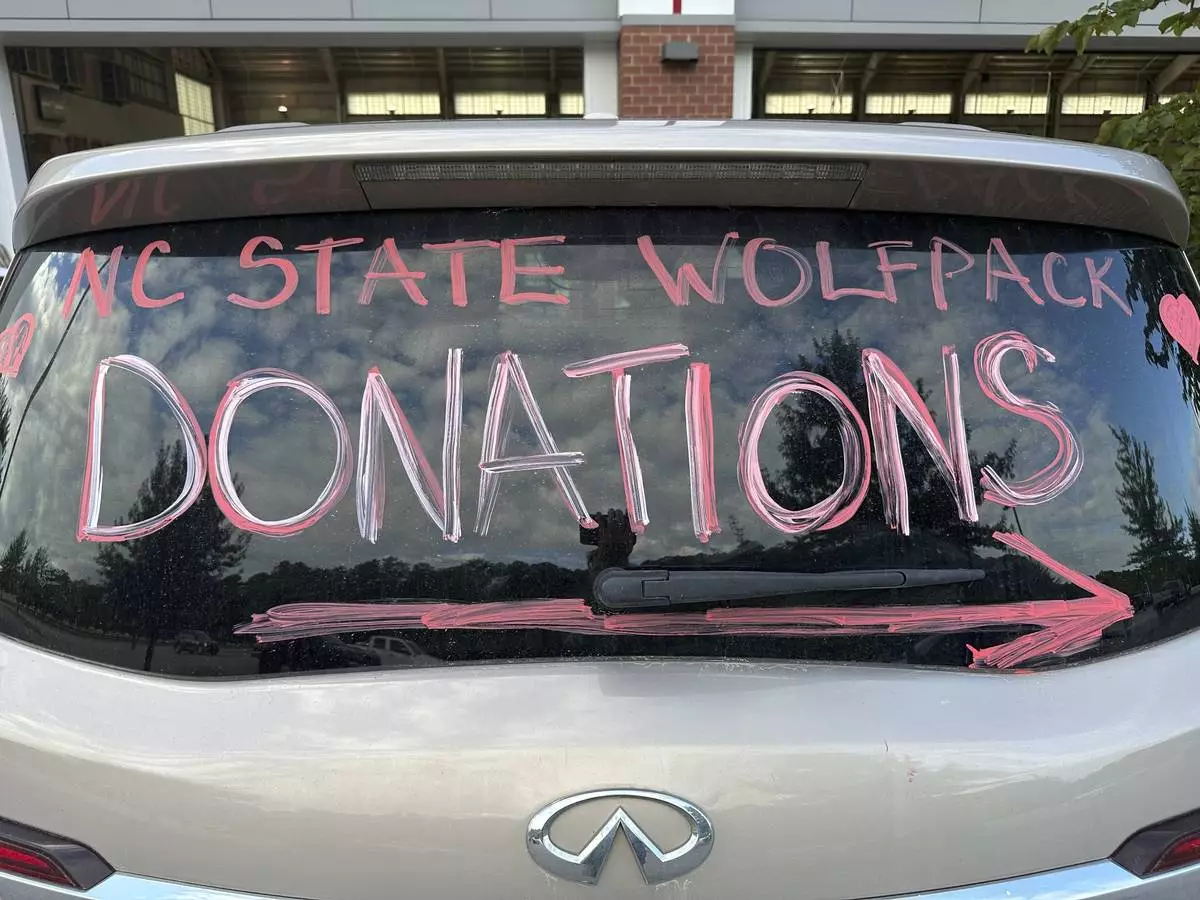

A makeshift sign in a vehicle window helps direct people arriving at a donation drive led by N.C. State defensive end Davin Vann to collect supplies to help Hurricane Helene victims in western North Carolina, Wednesday, Oct. 2, 2024 in Raleigh, N.C. (AP Photo/Aaron Beard)

A woman walks to her damaged home in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene, Thursday, Oct. 3, 2024, in Pensacola, N.C. (AP Photo/Mike Stewart)

A helicopter lands at the volunteer fire station in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene, Thursday, Oct. 3, 2024, in Pensacola, N.C. (AP Photo/Mike Stewart)

Homes lie in a debris field in the aftermath of Hurricane Helene, Thursday, Oct. 3, 2024, in Pensacola, N.C. (AP Photo/Mike Stewart)

SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — They began a pilgrimage that thousands before them have done. They boarded long flights to their motherland, South Korea, to undertake an emotional, often frustrating, sometimes devastating search for their birth families.

These adoptees are among the 200,000 sent from South Korea to Western nations as children. Many have grown up, searched for their origin story and discovered that their adoption paperwork was inaccurate or fabricated. They have only breadcrumbs to go on: grainy baby photos, names of orphanages and adoption agencies, the towns where they were said to have been abandoned. They don’t speak the language. They’re unfamiliar with the culture. Some never learn their truth.

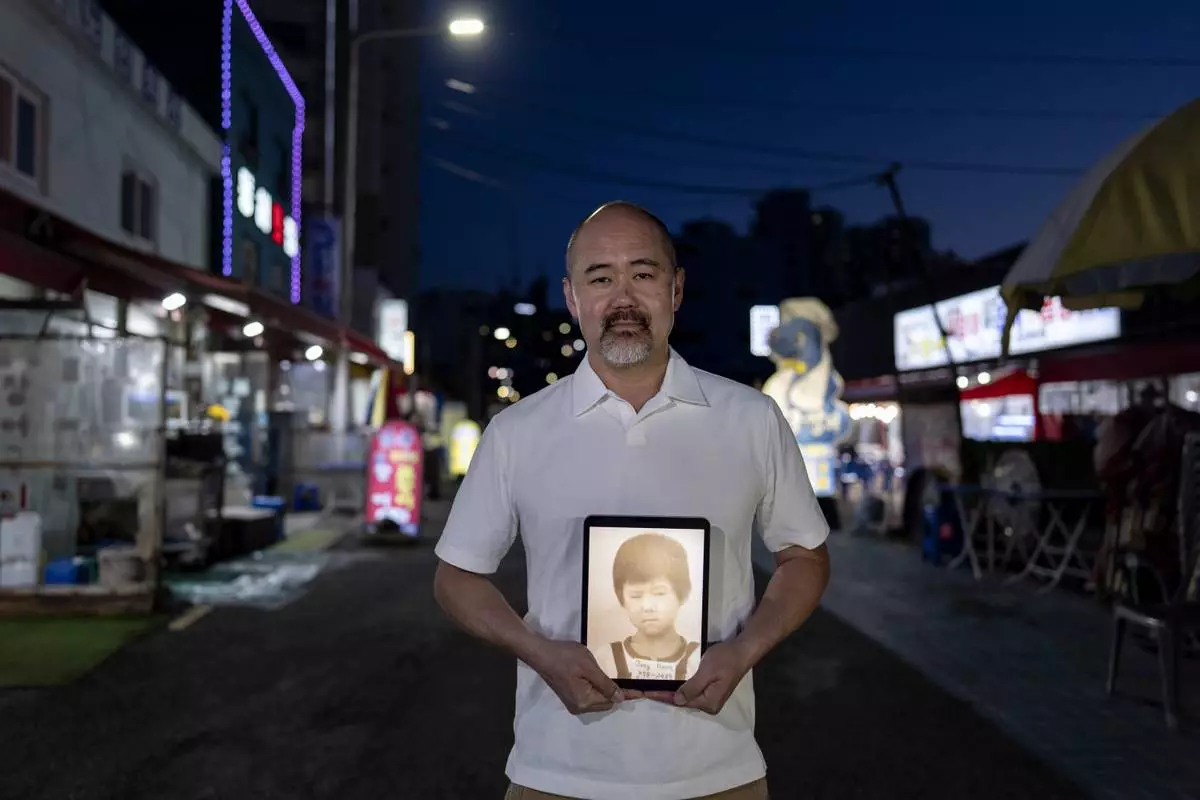

“I want my mother to know I’m OK and that her sacrifice was not in vain,” says Kenneth Barthel, adopted in 1979 at 6 years old to Hawaii.

He hung flyers all over Busan, where his mother abandoned him at a restaurant. She ordered him soup, went to the bathroom and never returned. Police found him wandering the streets and took him to an orphanage. He didn’t think much about finding his birth family until he had his own son, imagined himself as a boy and yearned to understand where he came from.

He has visited South Korea four times, without any luck. He says he’ll keep coming back, and tears rolled down his cheeks.

Some who make this trip learn things about themselves they’d thought were lost forever.

In a small office at the Stars of the Sea orphanage in Incheon, South Korea, Maja Andersen sat holding Sister Christina Ahn’s hands. Her eyes grew moist as the sister translated the few details available about her early life at the orphanage.

She had loved being hugged, the orphanage documents said, and had sparkling eyes.

“Thank you so much, thank you so much,” Andersen repeated in a trembling voice. There was comfort in that — she had been hugged, she had smiled.

She’d come here searching for her family.

“I just want to tell them I had a good life and I’m doing well,” Andersen said to Sister Ahn.

Andersen had been admitted to the facility as a malnourished baby and was adopted at 7 months old to a family in Denmark, according to the documents. She says she’s grateful for the love her adoptive family gave her, but has developed an unshakable need to know where she came from. She visited this orphanage, city hall and a police station, but found no new clues about her birth family.

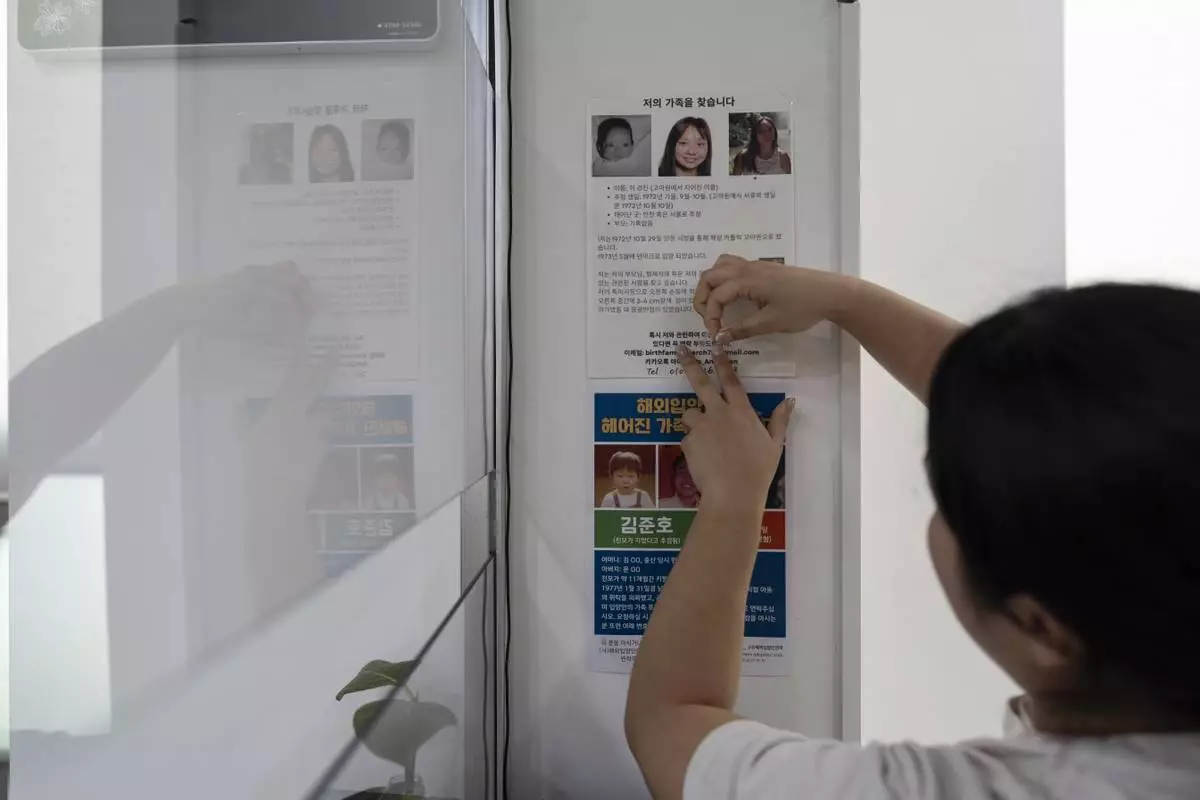

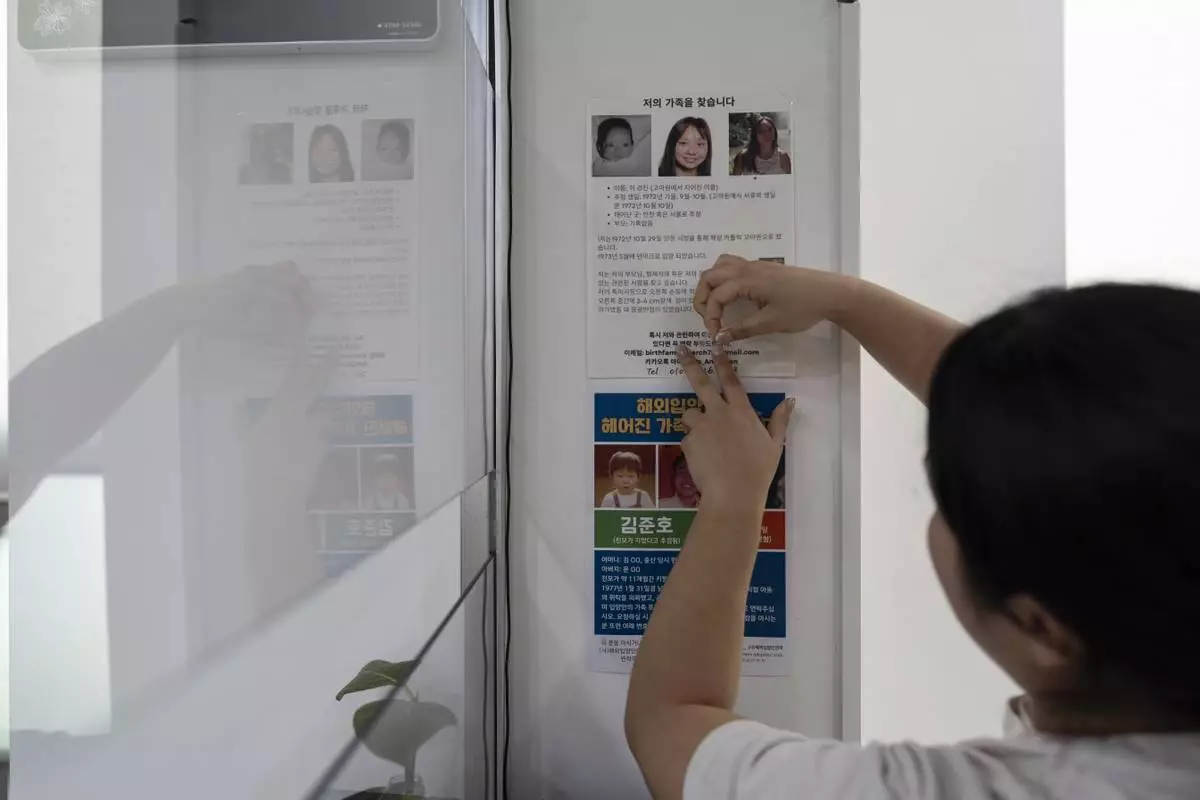

Still she remains hopeful, and plans to return to South Korea to keep trying. She posted a flyer on the wall of a police station not far from the orphanage, just above another left by an adoptee also searching for his roots.

Korean adoptees have organized, and now they help those coming along behind them. Non-profit groups conduct DNA testing. Sympathetic residents, police officers and city workers of the towns where they once lived often try to assist them. Sometimes adoption agencies are able to track down birth families.

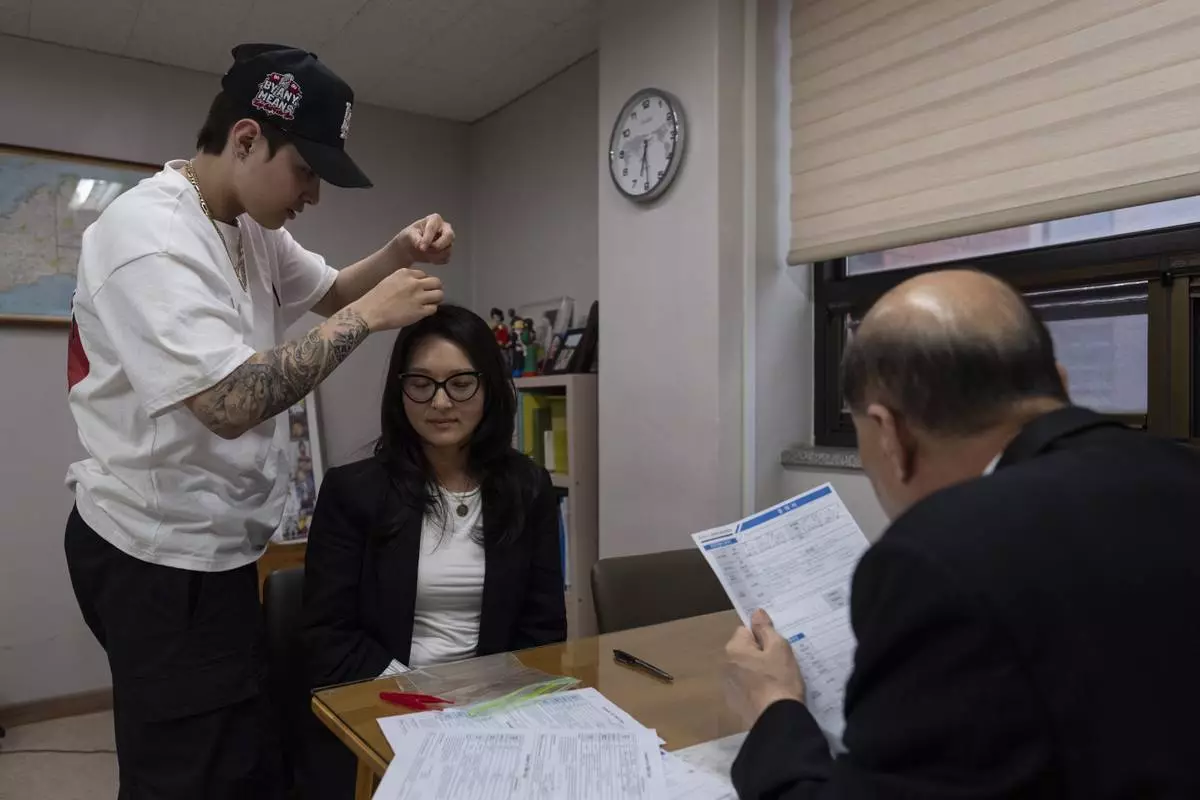

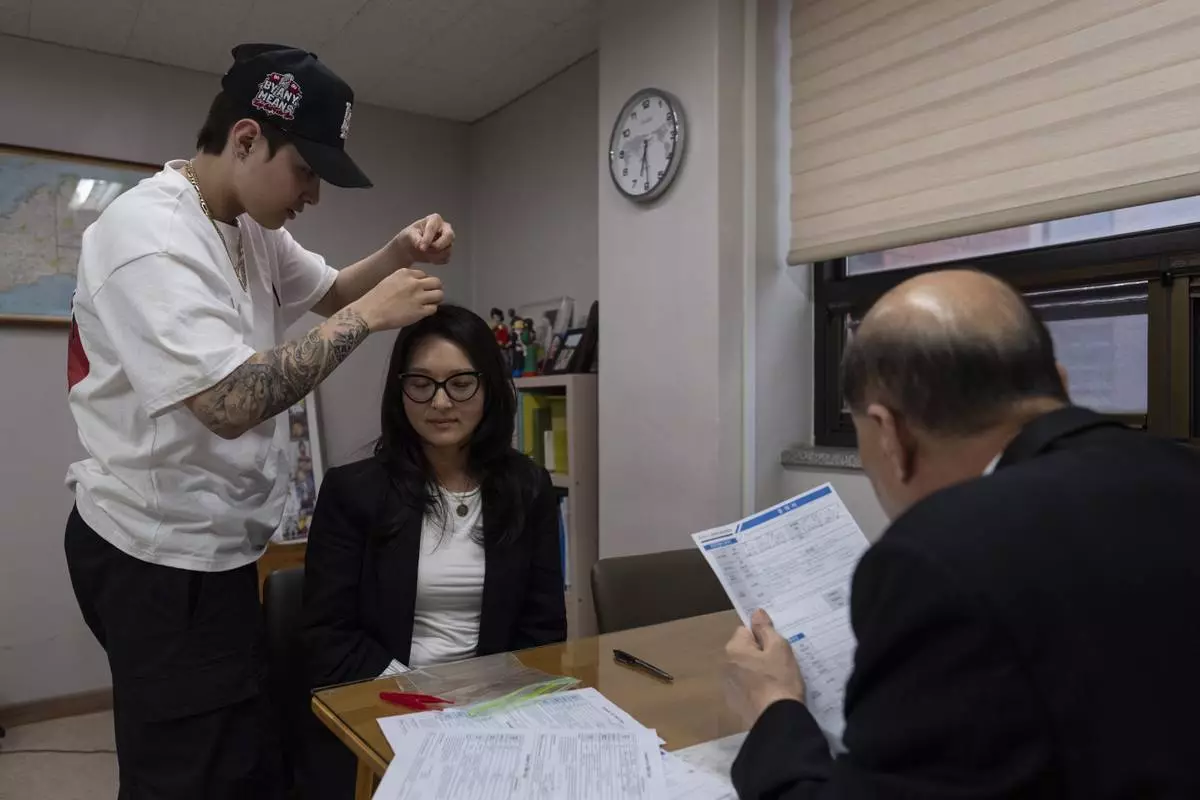

Nearly four decades after her adoption to the U.S., Nicole Motta in May sat across the table from a 70-year-old man her adoption agency had identified as her birth father. She typed “thanks for meeting me today” into a translation program on her phone to show him. A social worker placed hair samples into plastic bags for DNA testing.

But the moment they hugged, Motta, adopted to the United States in 1985, didn’t need the results — she knew she’d come from this man.

“I am a sinner for not finding you,” he said.

Motta’s adoption documents say her father was away for work for long stretches and his wife struggled to raise three children alone. He told her she was gone when he came back from one trip, and claimed his brother gave her away. He hasn’t spoken to the brother since, he said, and never knew she was adopted abroad.

Motta’s adoption file leaves it unclear whether the brother had a role in her adoption. It says she was under the care of unspecified neighbors before being sent to an orphanage that referred her to an adoption agency, which sent her abroad in 1985.

She studied his face. She wondered if she looks like her siblings or her mother, who has since died.

“I think I have your nose,” Motta said softly.

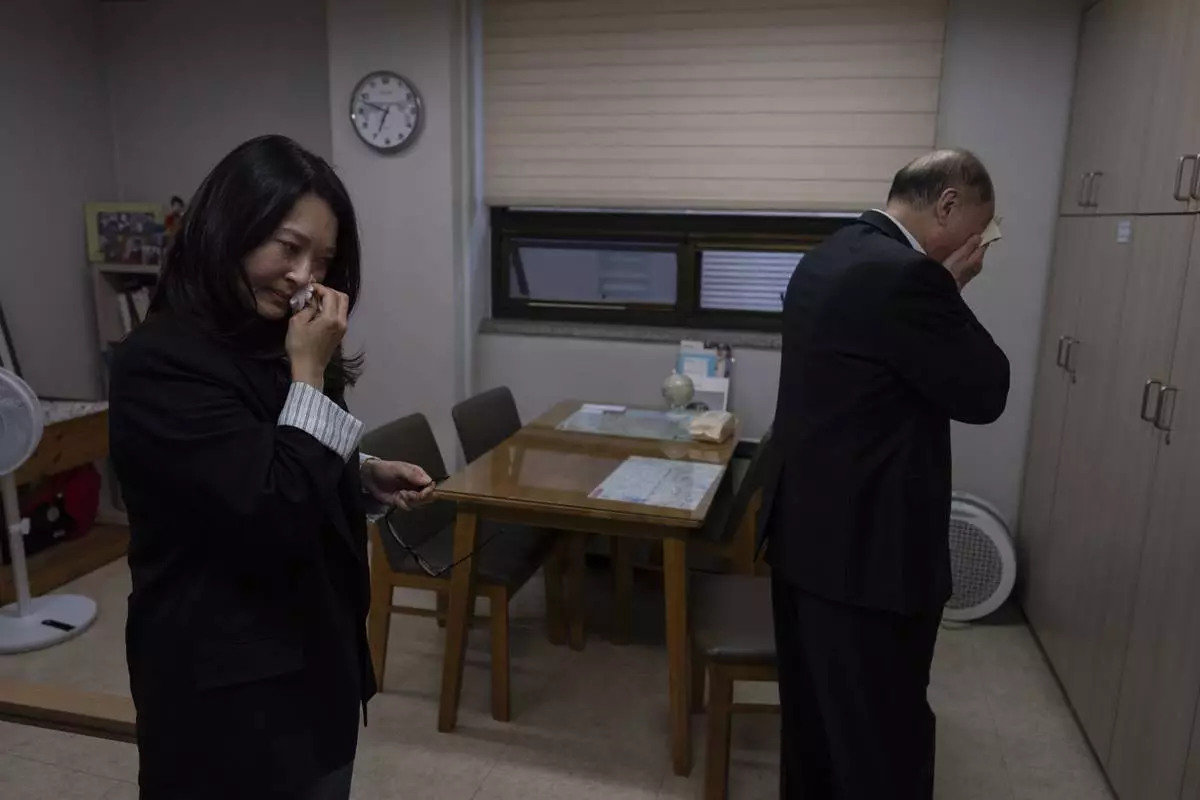

They both sobbed.

This story is part of an ongoing investigation led by The Associated Press in collaboration with FRONTLINE (PBS). The investigation includes an interactive and documentary, South Korea’s Adoption Reckoning. Contact AP’s global investigative team at Investigative@ap.org.

A teardrop rolls down the cheek of Kenneth Barthel, who was adopted from South Korea at the age of six, as he sits in a minivan in Busan, South Korea, Friday, May 17, 2024, after spending the day trying to uncover the details of his early life and find his birth family. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

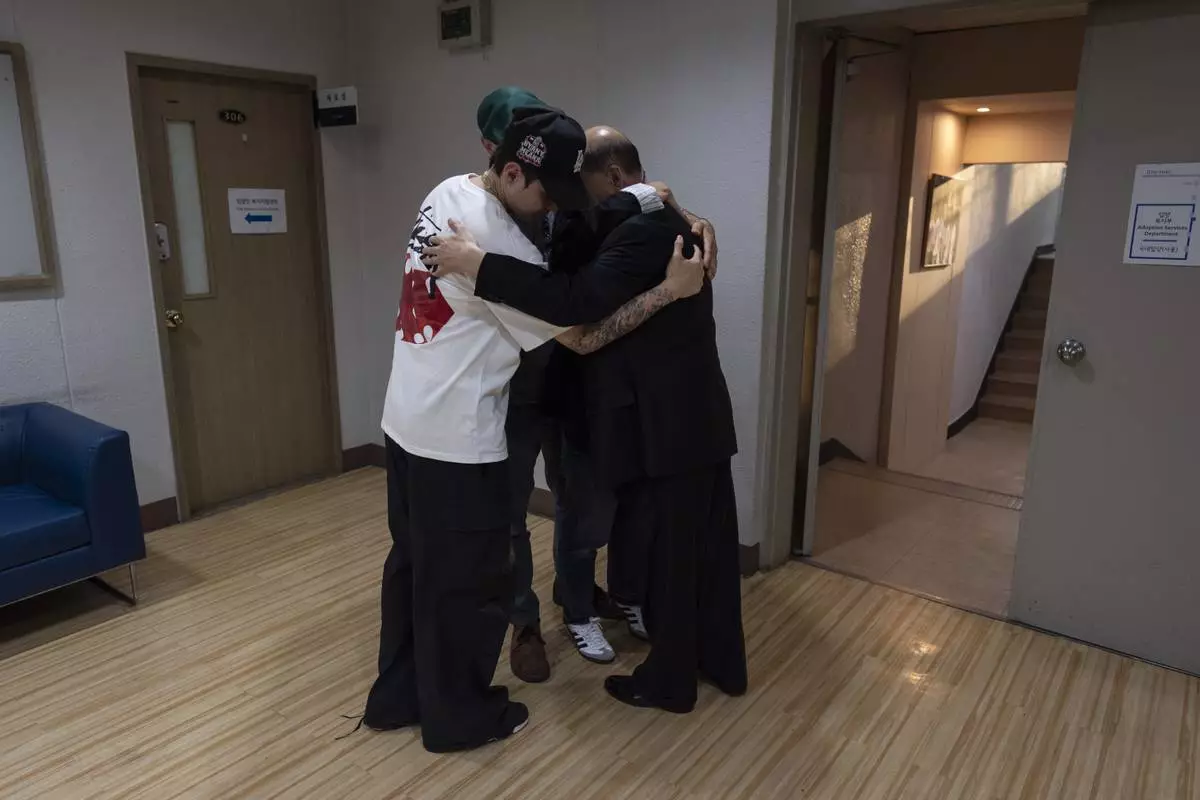

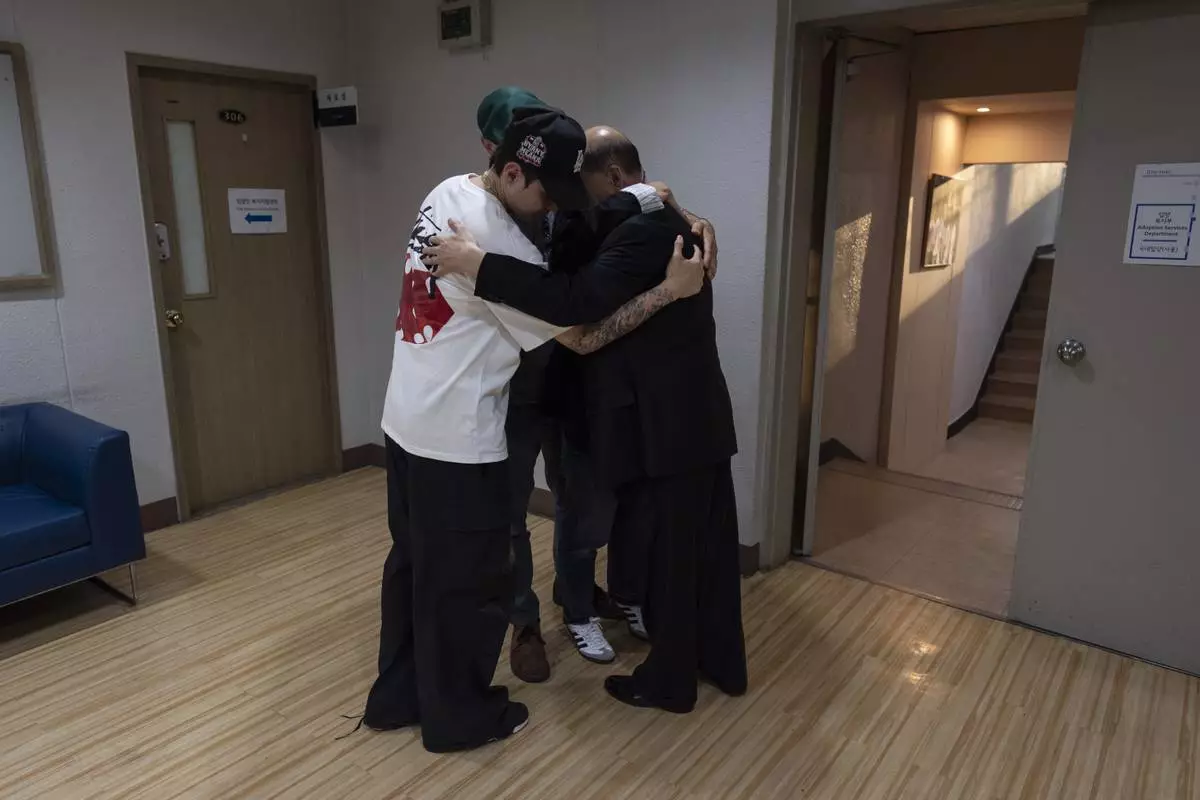

Jang Dae-chang hugs his daughter, Nicole Motta, and her family at the Eastern Social Welfare Society in Seoul on Friday, May 31, 2024, following their emotional first meeting. Motta, whose Korean name is Jang Hyeon-jung, was adopted by a family in Alabama, United States, in 1985. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

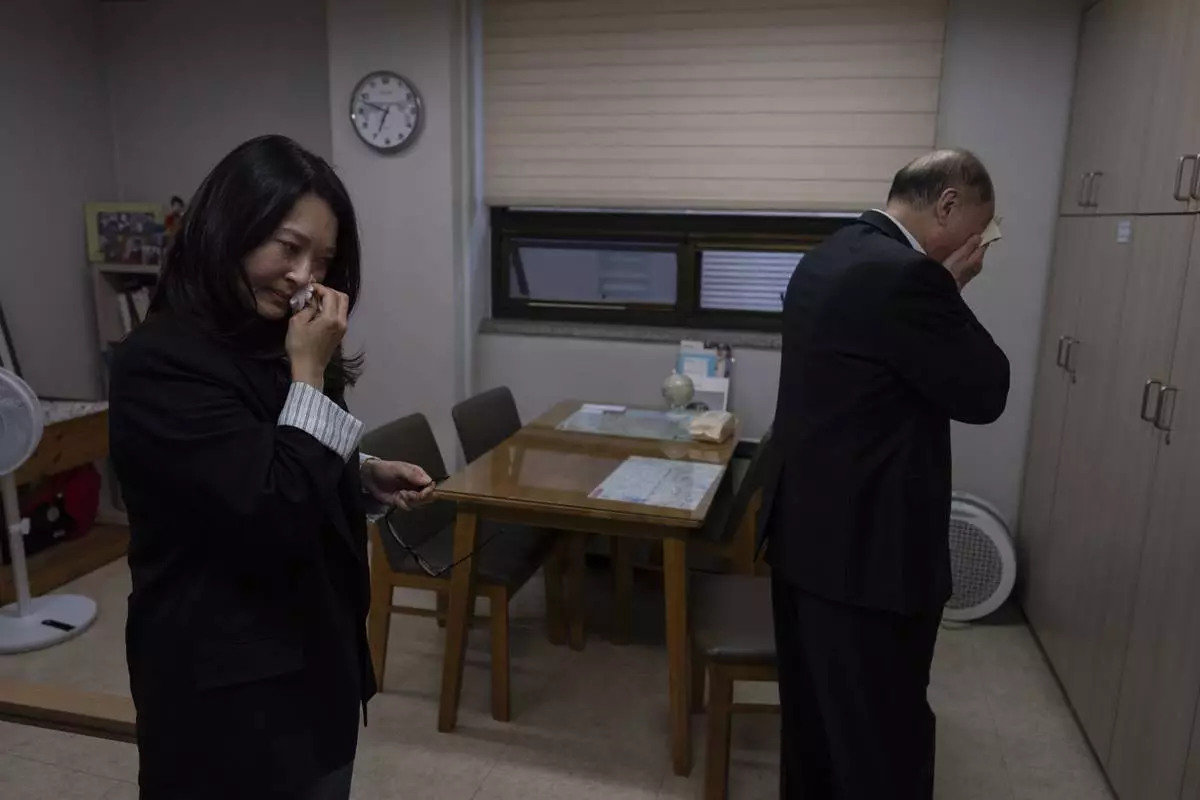

Adoptee Nicole Motta, left, and her birth father, Jang Dae-chang, wipe tears after an emotional reunion at the Eastern Social Welfare Society in Seoul, Friday, May 31, 2024. The moment they hugged, Motta, adopted to the United States in 1985, didn't need DNA test results, she knew she'd come from this man. "I am a sinner for not finding you," he said. "I think I have your nose," Motta said softly. They both sobbed. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Nicole Motta, an adoptee visiting South Korea to look for her birth family, types "thank you for meeting me today," on her smartphone to translate it into Korean, as she meets her birth father for the first time at the Eastern Social Welfare Society in Seoul, Friday, May 31, 2024. Motta's adoption documents say her father was away for work for long stretches and his wife struggled to raise three children alone. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Nicole Motta's son, Adler, collects hair samples from his mother for a DNA test as her birth father, Jang Dae-chang, reviews the paperwork at the Eastern Social Welfare Society in Seoul, South Korea, Friday, May 31, 2024. The two were reunited for the first time since she was adopted by a family in Alabama, United States, in 1985. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Nicole Motta, left, turns to see her birth father, Jang Dae-chang, as he enters the room at the Eastern Social Welfare Society in Seoul, South Korea, Friday, May 31, 2024, as they're reunited for the first time since she was adopted in 1985 by a family in Alabama. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Nicole Motta, an adoptee visiting from Los Angeles to search for her birth family, visits Bucheon, South Korea, where she was born, Thursday, May 30, 2024. Many adoptees have grown up and are searching for their origin story. They have few details to go on. They don't speak the language. They're unfamiliar with the culture. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Nicole Motta, second from left, an adoptee visiting from Los Angeles, chats with Paek Kyeong-mi from Global Overseas Adoptees' Link, during a break from searching for Motta's birth family in Bucheon, South Korea, Thursday, May 30, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Holding a flyer asking for help to find adoptee Nicole Motta's birth family, long-time resident An Bok-rye knocks on the door of an apartment building where Motta's home once stood in Bucheon, South Korea, Thursday, May 30, 2024. Sympathetic residents, police officers and city workers of the towns where they once lived often try to assist adoptees searching for their origin story. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Nicole Motta, left, an adoptee visiting from Los Angeles to search for her birth family, visits the neighborhood where she was born in Bucheon, South Korea, Thursday, May 30, 2024. Her son, Adler, second from left, walks alongside long-time resident An Bok-rye who is helping with her search. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Nicole Motta, an adoptee visiting from Los Angeles, holds a tablet displaying a childhood picture, while traveling to search for her birth family in Yongin, South Korea, Thursday, May 30, 2024. Motta, whose Korean name is Jang Hyeon-jung, visited the site that used to be the orphanage where she stayed until her adoption. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

The flag of South Korea is displayed at the Overseas Korean Adoptees Gathering in Seoul, South Korea, Tuesday, May 21, 2024. Korean adoptees have organized, and now they help those coming along behind them searching for their origin story. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

A city employee posts a flyer with photos of adoptee Maja Andersen from various ages in life and details about her birth search on the wall of a police station in Incheon, South Korea, Monday, May 20, 2024, above another left by an adoptee also searching for his roots. Andersen was adopted to a family in Denmark when she was an infant. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Maja Andersen, an adoptee visiting from Denmark to search for her birth family, hugs Sister Christina Ahn at Star of the Sea orphanage in Incheon, South Korea, Monday, May 20, 2024, while visiting the facility to look for details of her adoption. She had loved being hugged, the orphanage documents said, and had sparkling eyes. "Thank you so much, thank you so much," Andersen repeated in a trembling voice. There was comfort in that, she had been hugged, she had smiled. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Maja Andersen, an adoptee visiting from Denmark to search for her birth family, visits the Star of the Sea Orphanage in Incheon, South Korea, Monday, May 20, 2024, where she stayed until her adoption at seven months old. She visited the facility to look for documents in hopes of finding her family. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Maja Andersen, top, an adoptee visiting from Denmark to search for her birth family, holds the hands of Sister Christina Ahn at Star of the Sea orphanage in Incheon, South Korea, Monday, May 20, 2024, during her visit to look for documents in hopes of finding her family. She stayed at the facility until her adoption at seven months old. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Maja Andersen, right, an adoptee visiting from Denmark to search for her birth family, and her daughter, Yasmin, attend the Overseas Korean Adoptees Gathering in Seoul, South Korea, Tuesday, May 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Photos of adoptees participating at the Overseas Korean Adoptees Gathering are displayed on a large screen during the conference in Seoul, South Korea, Tuesday, May 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Maja Andersen, front row third from left, an adoptee visiting from Denmark to search for her birth family, holds a South Korean flag with others while taking a group photo at the Overseas Korean Adoptees Gathering in Seoul, South Korea, Tuesday, May 21, 2024. These adoptees are among the 200,000 sent away from Korea to Western nations as children. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Maja Andersen sits for a photo in her hotel room, holding a tablet displaying her baby photo taken before her adoption to Denmark, as she visits Seoul, South Korea to search for her birth family, Monday, May 20, 2024. Andersen is among thousands of Korean adoptees who have taken a pilgrimage to their motherland for an emotional, often frustrating, sometimes devastating search for their origin story. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Kenneth Barthel, left, who was abandoned and later adopted to the United States at 6 years old, and his wife, Napela, comfort each other as they leave the Busan Metropolitan City Child Protection Center in Busan, South Korea, Friday, May 17, 2024, after searching for documents that could lead to finding his birth family. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Kenneth Barthel, right, who was adopted to the United States at 6 years old, talks with diners in the neighborhood where he remembers being abandoned by his mother, in Busan, South Korea, Friday, May 17, 2024. Barthel was posting flyers in the area featuring his photos in the hopes of finding his birth family. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Restaurant owner Shin Byung-chul looks from behind a flyer he put up of Kenneth Barthel, who was abandoned in the area as a child and later adopted to Hawaii at 6 years old, at his restaurant in Busan, South Korea, Friday, May 17, 2024. Barthel has visited Korea four times to search for his birth family. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Kenneth Barthel, left, helps Shin Byung-chul post a flyer with photos of Barthel at various ages in his life, on the wall of his restaurant in Busan, South Korea, Friday, May 17, 2024, as Barthel's daughter, Amiya, rear, looks on. Barthel's mother had ordered him soup in a restaurant in the area when he was 6 years old, went to the bathroom and never returned. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

Kenneth Barthel, who was adopted by a single parent in Hawaii at 6 years old, is hugged by his wife, Napela, at the Sisters of Mary in Busan, South Korea, Friday, May 17, 2024. In the foreground, Sister Bulkeia, left, and Paek Kyeong-mi from Global Overseas Adoptees' Link discuss a flyer designed to uncover the details of Barthel's early life and find his birth family. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

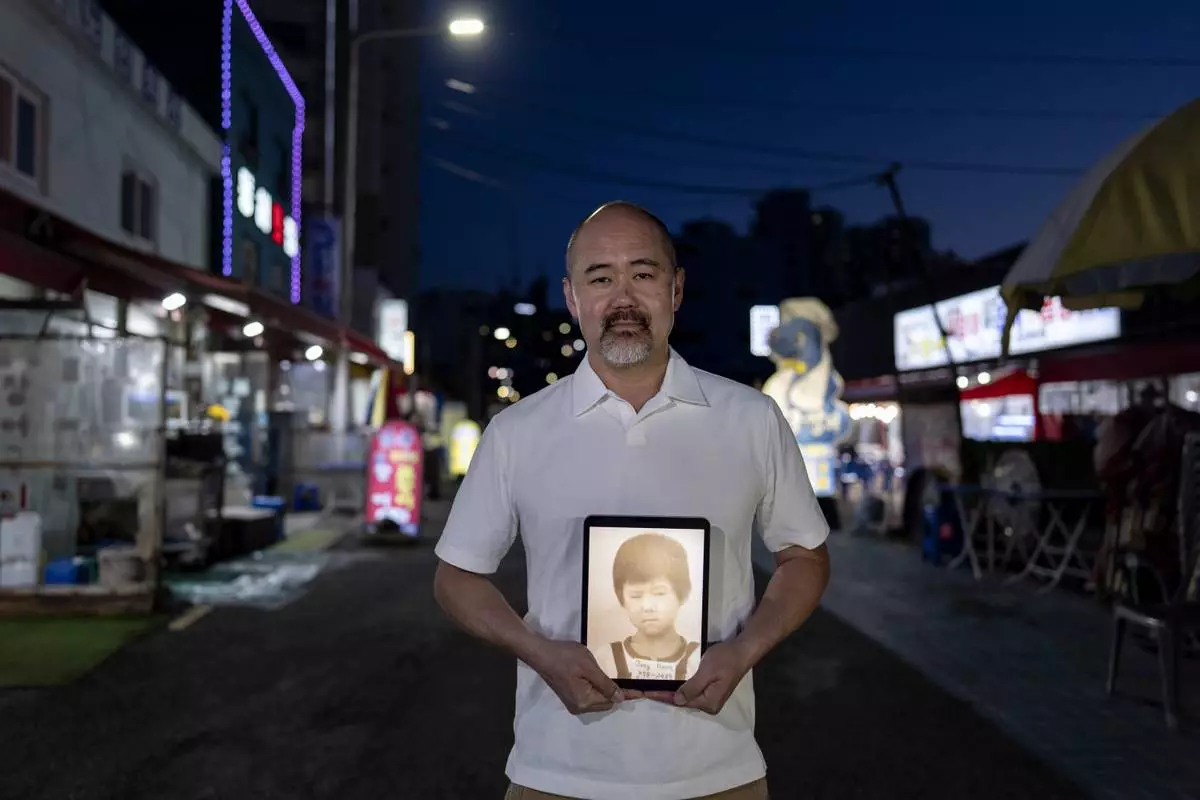

Kenneth Barthel, adopted from South Korea to Hawaii in 1979 at 6 years old, holds a tablet showing his childhood photo in Busan, South Korea, Thursday, May 16, 2024. Barthel is looking for his birth family in Busan where he believes he was abandoned when his mother ordered soup for him in a restaurant and never returned. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)