KAMPONG PHLUK, Cambodia (AP) — Em Phat, 53, studies his eel tanks with the intensity of a man gambling with his livelihood.

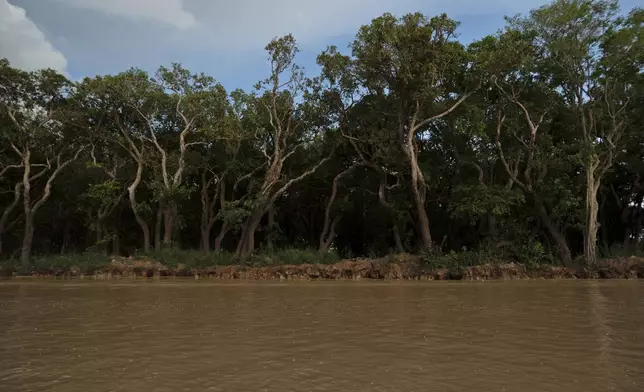

For millennia, fishermen like him have relied on the bounty of the Tonle Sap in Cambodia, Southeast Asia’s largest lake and the epicenter of the world’s most productive inland fishery. But climate change, dams upstream on the Mekong River that sustains the lake, and deforestation in the region have changed everything.

There aren't enough fish and living by the lake has become dangerous as storms intensify due to global warming. “Being a fisherman is hard,” he said.

Phat hopes that raising eels — a delicacy in Asian markets like China, Japan and South Korea — will provide a way forward. He raises eels in different tanks: translucent eel eggs bob gently in Small glass aquariums. Voracious glassy larvae swim in plastic tanks. Larger tubs have bicycle tires to provide places for juvenile eels to hide.

Raising eels can be profitable but it's risky. Eels are notoriously difficult and expensive to raise. They need constant pure, oxygenated water and special food and are susceptible to diseases. Phat lost many eels when a power cut stopped his oxygen pumps, killing the fish. But he's optimistic about the future. Living on land, instead of on the lake, also means that his wife, Luy Nga, 52, can grow vegetables to eat and sell, so they are making enough money to get by.

“The eels have value and can also be exported to China and other countries in the future,” he said.

That fishermen like Phat can no longer rely on the Tonle Sap, literally the “Great Lake,” for their livelihood reflects how much has changed. The lake used to more than quadruple in size to an area larger than the country of Qatar during the rainy season, inundating native forests and creating the perfect breeding ground for diverse fish to thrive.

The "flood pulse,” a natural process of periodic flooding and droughts in the river system helped make the Mekong Basin the world’s largest freshwater fishery, with nearly 20% of all freshwater fish worldwide caught there, according to the think tank Stimson Center in Washington. More than 3 million people live and fish by the lake: a third of all 17 million Cambodians rely on the fisheries sector and up to 70% of Cambodia’s intake of animal protein is from fish.

But dams upstream in China and Laos are cutting the Mekong's flow, weakening that flood pulse. The lakes have been depleted by overfishing and much of the forest surrounding it has been logged or burned for farmland. Cambodian authorities are reluctant to estimate the extent that fish stocks have declined.

This year, the flood pulse was delayed by about two months, according to the Mekong Dam Monitor, a research project.

In this shattered ecosystem, raising eels or other fish can provide fishermen like Phat with a “buffer,” said Zeb Hogan, a fish biologist at the University of Nevada who has worked in the region for decades. “Aquaculture, such as eel farming, is a way for people to take more control over their income source and livelihood,” he said, adding that it also allows them to raise fish that they know will fetch higher prices.

Phat is one of more than thousands helped by a program run by the Britain-based nonprofit VSO to boost incomes of people living by Tonle Sap. VSO provides his baby eels and has taught him how to raise them.

Eels are in high demand in Cambodia and elsewhere, said Sum Vy, 38, a coordinator at VSO, so they're profitable. When fishermen know how to farm eels and hatch the babies, others can follow.

“Not only can he or she earn the money to support their family, they can share this knowledge and skill with other people,” he said.

Expanding aquaculture is helping increase Cambodian exports. Its fish production increased 24-fold in the two decades leading up to 2021 and, unlike its neighbors, most of its fish catch is inland, according to the Food and Agricultural Organization or FAO. Much of it is consumed domestically and exports have grown sluggishly. Earlier this year, the government launched a scheme to improve fish processing technologies and address food safety concerns, hoping to begin exporting more fish to Europe next year.

Cambodia has signed trade agreements with China and began shipping frozen eels to Shanghai last year.

“This export will contribute to economic growth, creating jobs for our farmers and fishermen,” Heng Mengty, the export manager of the Cambodian fish exporter told China's official Xinhua news agency.

The promised growth can’t come soon enough for Cambodians living in fishing communities around the lake. Some families live in homes that float year round, others on homes built on stilts up to 8-meters-high (26 feet), to keep them above floodwaters during the rainy season. Fishing is the only form of subsistence for many, but signs of decay are evident. Fishing nets catch only very small fish, or worse, nothing at all. Families speak of giant fish that are now rarely seen. The catch is a fraction of what it used to be.

Even 10 years ago, Som Lay, a 29-year-old fisherman said, the lake was teeming with fish. But illegal fishing has increased and some families have already given up fishing and are trying to find land where they can grow rice.

“The entire village — my family and others — is facing these difficulties,” he said.

Associated Press journalist Sopheng Cheang contributed to this report.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

A fisherman fishes in the Tonle Sap in Kampong Chhnang province, Cambodia, Thursday, Aug. 1, 2024, (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

A girl rides a bicycle at a floating village, by the Tonle Sap in Kampong Chhnang province, Cambodia, Thursday, Aug. 1, 2024, (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

A fisher family in their home at a floating village, by the Tonle Sap in Kampong Chhnang province, Cambodia, Thursday, Aug. 1, 2024, (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

A local vendor sits at her grocery store at a floating village by the Tonle Sap in Kampong Chhnang province, Cambodia, Thursday, Aug. 1, 2024, (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

Locals fix their fishing nets at a floating village by the Tonle Sap in Kampong Chhnang province, Cambodia, Thursday, Aug. 1, 2024, (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

Children walk past a floating village, by the Tonle Sap in Kampong Chhnang province, Cambodia, Thursday, Aug. 1, 2024, (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

Boats of fisherfolk are anchored by a floating village, by the Tonle Sap in Kampong Chhnang province, Cambodia, Thursday, Aug. 1, 2024, (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

Trees stand on the edge of Tonle Sap lake, forming part of the surrounding forests, much of which has been logged or burned for farmland, in Cambodia, Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. (AP Photo/Aniruddha Ghosal)

Eel eggs float in a tank raised by eel farmer in Kampong Chhnang province, Cambodia, Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Aniruddha Ghosal)

A fisherman sits on a boat in the Tonle Sap lake, Siem Reap, Cambodia, Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. (AP Photo/Aniruddha Ghosal)

A bucket of eels for sale in Siem Reap province, Cambodia, Friday, Aug. 2, 2024. (AP Photo/Anton L. Delgado)

An aerial view of Em Phat's eel farm on the edges of Tonle Sap lake, north of Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Anton L. Delgado)

Eel farmer Luy Nga, 52, sits next to jars where eels are reared at Tonle Sap complex. north of Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

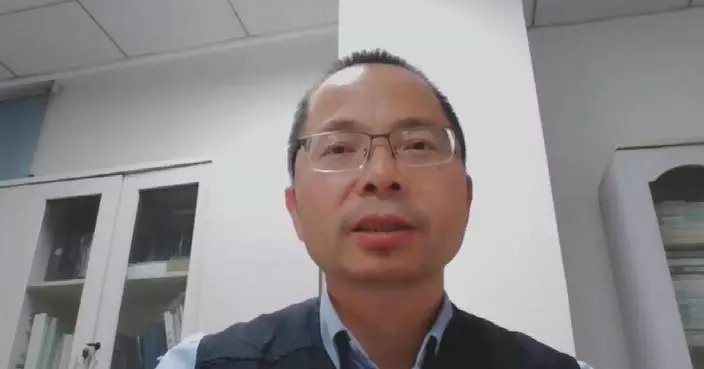

Em Phat, 53, stands in his eel farm at Tonle Sap complex, north of Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

Eel farmer Em Phat, 53, works in his eel rearing place at Tonle Sap complex, north of Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

Eel farm owner Em Phat, 53, works in Tonle Sap complex, north of Phnom Penh Cambodia, Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

Baby eels swim in a tank at Tonle Sap complex, north of Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

An eel crawls in a pool as its farm owner replaces water in the eel rearing pool at Tonle Sap complex, north of Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)

Em Phat, 53, eel farm owner, holds an eel in an eel rearing pool at Tonle Sap complex, north of Phnom Penh, Cambodia, Wednesday, July 31, 2024. (AP Photo/Heng Sinith)