WASHINGTON (AP) — Sixteen-year-old Billy's friends at his rural high school in the South don't know he was one of thousands of children separated from their parents at the U.S.-Mexico border under then-President Donald Trump's zero tolerance immigration policy.

At school, where he plays football and soccer, Billy doesn't talk about what he went through — that his father was told six years ago that Billy was being given up for adoption and feared he would never see his son again.

With the United States on the verge of an election that could put Trump back in office, Billy wants people to know that what happened to him and several thousand other children reverberates still. Some families have not been reunited, and many of those together in the U.S. have temporary status and fear a victorious Trump carrying out promised mass deportations.

“It was a very painful thing that happened to us,” said Billy, who was 9 at the time. He did not want his full name or the state he lives in identified for fear of endangering his family’s asylum application.

Trump has made his immigration views central to his campaign, accusing the Biden administration and Vice President Kamala Harris, the Democratic nominee for president, of failing to secure the southern border. Harris has not made immigration a campaign focus but has raised Trump's zero tolerance policy, one of his most contentious immigration actions as president.

The Trump administration aimed to criminally prosecute all adults coming across the border illegally. Parents were separated from their children, who were transferred to shelters nationwide.

Trump and his campaign did not say specifically whether he would revive the practice if he wins on Nov. 5. He has previously defended it, including claiming without evidence during a Univision interview last year that it “stopped people from coming by the hundreds of thousands.”

"President Trump will restore his effective immigration policies, implement brand new crackdowns that will send shockwaves to all the world’s criminal smugglers, and marshal every federal and state power necessary to institute the largest deportation operation of illegal criminals, drug dealers, and human traffickers in American history,” said Karoline Leavitt, the Trump campaign’s press secretary.

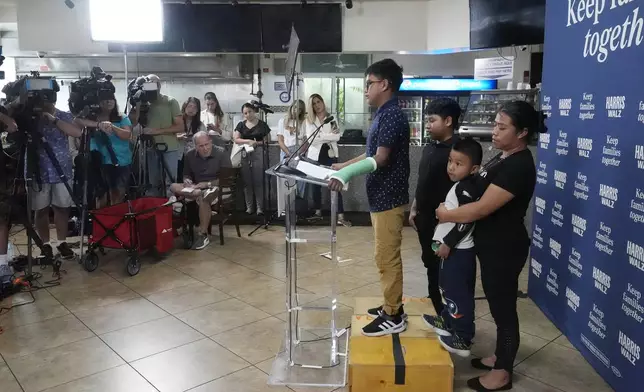

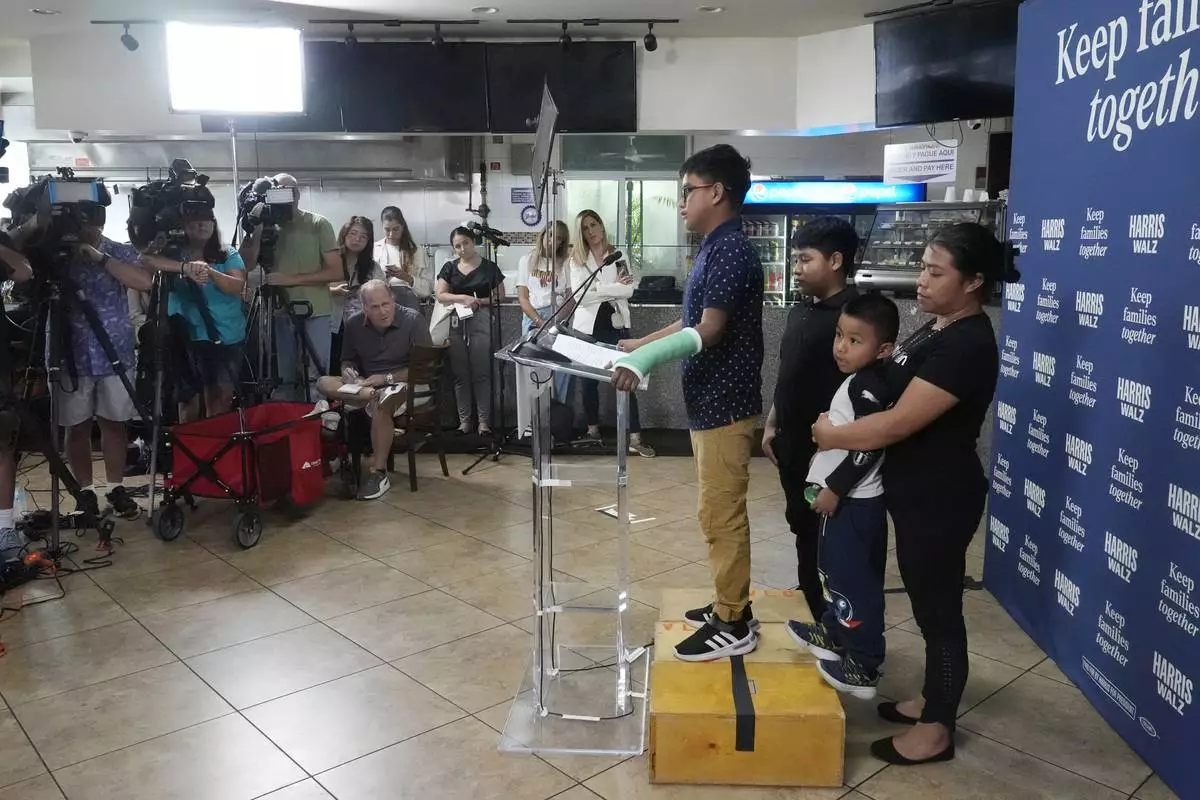

The Harris campaign held a event this month featuring children who were separated from their families, aiming to draw attention to Trump's policies.

Billy, who spoke at the event, is part of a group of children who are sharing their stories in short social media videos to highlight the zero tolerance policy. Billy and his father also have visited lawmakers in Washington.

Billy told The Associated Press that even though he doesn't usually talk about his experiences, he and the others are “making sure that we raise our voices and that we share our stories” so something like this never happens again.

Most of the families who were separated years ago are in legal limbo, their immigration status in doubt. Under a settlement announced last year between families and the Biden administration, the families have two years to apply for asylum under a more favorable process.

As the election nears, advocates say they have heard from families who were separated expressing fears about Trump, if elected, making good on promises to deport millions of people.

“The families we serve are scared and have a lot of questions about what a new Trump administration would mean for them,” said Anilú Chadwick Soltes, pro bono director for Together & Free, an organization launched in 2018 in response to the zero tolerance policy. The group works to help separated families.

The 2023 settlement barred future administrations from using family separation as a widespread policy until 2031. But advocates have concerns.

Christie Turner-Herbas, senior adviser with Kids in Need of Defense, said she worries about exceptions to the policy being exploited and says there has to be political will to enforce it.

The Trump administration's policy deviated from the general practice of keeping families with children together when they come to the southern border.

The goal was to dissuade people by criminally prosecuting everyone who crossed the border. For families, parents were prosecuted. Kids, who cannot be held in custody, were treated as unaccompanied minors and transferred to shelters.

After an outcry, Trump said on June 20, 2018, that he was ending the policy. Six days later, a judge ordered the government to reunite the families, thousands of whom had been separated. Agencies didn’t have their computer systems properly linked, making it difficult to reunite families. Many parents were deported, complicating things even more.

When Democrat Joe Biden became president, he created a task force to reunite families. Building on efforts by groups that had sued the Trump administration, the task force identified about 5,000 children were separated, and about 1,400 aren't confirmed to be reunited with their families.

Some are in the process. Others are believed to have reunited in the U.S. but aren't coming forward, possibly fearing government interaction. For others, no valid contact information exists, so the search continues.

The American Civil Liberties Union, which brought a lawsuit against the Trump administration that helped end family separation, puts the number of separated children closer to 5,500.

Lee Gelernt, lead counsel in that lawsuit, said the ACLU estimates that as many as 1,000 families are still apart.

“Some little children have now spent nearly their entire lives without their parents," he said.

The task force runs a website where families can register to be reunited, and it works with the International Organization for Migration to help those families with things like getting a passport to come to the U.S. The task force's director has traveled to families' home countries to do radio announcements looking for parents.

Advocacy groups also have been instrumental.

Justice in Motion, which works with advocates in Mexico and Central America to track down parents, uses a last known address and talks to neighbors, local businesses, hospitals, schools — anyone who might know where that person is.

But they're stuck with poor recordkeeping that's now outdated, said Nan Schivone, the organization's legal director.

Families and separated children have struggled with the fallout.

For 22-year-old Efrain, there was guilt. Efrain said his father didn't want to bring him to the U.S. in 2018, but he pushed for it. When they were eventually separated, Efrain wondered whether it would have been better if his father had been alone.

His father was sent back to Guatemala. Efrain, who didn't want his full name used because he fears the repercussions, was placed in a shelter for unaccompanied children for roughly five months.

His father has diabetes, and Efrain worried about his health. When they could do a video call after Efrain left the shelter, he noticed how much thinner his father looked.

Three years later, they reunited at the Atlanta airport. Ever since, Efrain says he's been trying to make up for lost time. He says he struggles with anxiety and loneliness, echoing the isolation he felt after being separated from his father.

“It’s like I’m alone in a room locked up,” he said in Spanish.

Billy's father, meanwhile, still cries when he talks years later about what he and his son went through. He believes people have forgotten what happened and the families' trauma.

Billy says he's found purpose in sharing what he experienced: “I know that my story holds a lot of power."

Associated Press reporter Valerie Gonzalez in McAllen, Texas, contributed to this report.

FILE - Billy and his father, no last name given, pause after speaking at a Democratic Party campaign event about their experience of being separated at the U.S.- Mexico border during the Trump administration, Oct. 16, 2024, in Doral, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier, File)

FILE- Hamilton, no last name given, stands next to his family during a Democratic Party campaign event where he spoke of his experience on being separated from his mother when their crossed the U.S-Mexico border during the Trump administration, Oct. 16, 2024, in Doral, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier, File)

FILE- Christian and Hamilton, no last name given, speak during a Democratic Party campaign event about their experience on being separated from their mother Clairet when they crossed the U.S.- Mexico border during the Trump administration, Oct. 16, 2024, in Doral, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier, File)

FILE - Families that were separated at the U.S.- Mexico border during the Trump administration wait to speak at a Democratic party campaign event, Oct. 16, 2024, in Doral, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier, File)

FILE - Billy and his father, no last name given, speak at a Democratic Party campaign event, about their experience of being separated when they crossed the U.S.- Mexico border during the Trump administration, Oct. 16, 2024, in Doral, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier, File)