WILLIAMSBURG, Va. (AP) — A Virginia museum has nearly finished restoring the nation's oldest surviving schoolhouse for Black children, where hundreds of mostly enslaved students learned to read through a curriculum that justified slavery.

The museum, Colonial Williamsburg, also has identified more than 80 children who lined its pinewood benches in the 1760s.

Click to Gallery

Knob and tube electrical wiring at the Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Katie McKinney, is the Margaret Beck Pritchard Associate curator of Maps and Prints for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Elizabeth Drembus discusses the known family trees of some of the students that attended the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Janice Canaday, Colonial Williamsburg Foundations African American community engagement manager, stands outside near the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

The classroom of the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Matthew Webster, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's executive director of architectural preservation and research, speaks about the Williamsburg Bray School's construction on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Matthew Webster shows an original rail from the classroom of the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Janice Canaday, Colonial Williamsburg Foundations African American community engagement manager, in the classroom of the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Replicas of the books that students would have used at the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Katie McKinney speaks about the curriculum of the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Residue from the original plaster walls of the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Elizabeth Drembus, the genealogist at the Williamsburg Bray School Lab, speaks about her work on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Janice Canaday, Colonial Williamsburg Foundations African American community engagement manager, has traced her ancestors to the Williamsburg Bray School, on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

18th century nails shoved in between hand craved joints in the stairs leading up to the second floor of the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Katie McKinney, is the Margaret Beck Pritchard Associate curator of Maps and Prints for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

A dog's paw print (left of arrow) is seen in one of the chimney bricks at the Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

They include Aberdeen, 5, who was enslaved by a saddle and harness maker. Bristol and George, 7 and 8, were owned by a doctor. Phoebe, 3, was the property of local tavern keepers.

Another student, Isaac Bee, later emancipated himself. In newspaper ads seeking his capture, his enslaver warned Bee “can read.”

The museum dedicated the Williamsburg Bray School at a large ceremony on Friday, with plans to open it for public tours this spring. Colonial Williamsburg tells the story of Virginia’s colonial capital through interpreters and hundreds of restored buildings.

Smithsonian Institution Secretary Lonnie Bunch told the crowd outside the refurbished school that it was one of the most important historic moments of the last decade.

“History is an amazing mirror,” Bunch added. “It’s a mirror that challenges us and reminds us that, despite what we’ve achieved, despite all our ideals, America still is a work in progress. But oh, what an amazing work it is."

The Cape Cod-style home was built in 1760 and still contains much of its original wood and brick. It will anchor a complicated story about race and education, but also resistance, before the American Revolution.

The school rationalized slavery within a religious framework and encouraged children to accept their fates as God’s plan. And yet, becoming literate also gave them more agency. The students went on to share what they learned with family members and others who were enslaved.

“We don’t shy away from the fact that this was a pro-slavery school,” said Maureen Elgersman Lee, director of William & Mary’s Bray School Lab, a partnership between the university and museum.

But she said the school takes on a different meaning in the 21st century.

“It’s a story of resilience and resistance," Lee said. "And I put the resilience of the Bray School on a continuum that brings us to today."

To underscore the point, the lab has been seeking descendants of the students, with some success.

They include Janice Canaday, 67, who also is the museum's African American community engagement manager. Her lineage traces back to the students Elisha and Mary Jones.

“It grounds you,” said Canaday, who grew up feeling little connection to history. “That’s where your power is. And those are the things that give you strength — to know what your family has come through.”

The Bray School was established in Williamsburg and other colonial cities at the recommendation of founding father Benjamin Franklin. He was a member of a London-based Anglican charity that was named after Thomas Bray, an English clergyman and philanthropist.

The Bray School was exceptional for its time. Although Virginia waited until the 1800s to impose anti-literacy laws, white leaders across much of Colonial America forbid educating enslaved people, fearing literacy would encourage them to seek freedom.

The white teacher at the Williamsburg school, a widow named Ann Wager, taught an estimated 300 to 400 students, whose ages ranged from 3 to 10. The school closed with her death in 1774.

The schoolhouse became a private home before it was incorporated into William & Mary’s growing campus. The building was moved and expanded for various purposes, including student housing.

Historians identified the structure in 2020 through a scientific method that examines tree rings in lumber. Last year, it was transported to Colonial Williamsburg, which includes parts of the original city.

The museum and university have focused on restoring the schoolhouse, researching its curriculum and finding descendants of former students.

The lab has been able to link some people to the Jones and Ashby families, two free Black households that had students in the school, said Elizabeth Drembus, the lab's genealogist.

But the effort has faced steep challenges: Most enslaved people were stripped of their identities and separated from their families, so there are limited records. And only three years of school rosters have survived.

Drembus is talking to people in the region about their family histories and working backward. She also is sifting through 18th-century property records, tax documents and enslavers' diaries.

“When you’re talking about researching formerly enslaved people, records were kept very differently because they weren't considered people,” Drembus said.

Researching the curriculum has been easier. The English charity catalogued the books it sent to the schools, said Katie McKinney, an associate curator of maps and prints at the museum.

Materials include a small spelling primer, a copy of which was located in Germany, that begins with the alphabet and moves on to syllables, such as “Beg leg meg peg."

Students also received a more sophisticated speller, bound in sheepskin, as well as the Book of Common Prayer and other Christian texts.

Meanwhile, the schoolhouse has been mostly restored. About 75% of the original floor has survived, allowing visitors to walk where the children and teacher placed their feet.

Canaday, whose familial roots include two Bray School students, wondered on a recent visit if any of the children “felt safe in here, whether they felt loved.”

Canaday noted that the teacher, Wager, was the mother of at least two kids.

“Did some of her mothering bleed over into what she showed those children?” Canaday said. “There are moments when we forget to go by the rules and humanity takes over. I wonder how many times that happened in these spaces."

Knob and tube electrical wiring at the Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Katie McKinney, is the Margaret Beck Pritchard Associate curator of Maps and Prints for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Elizabeth Drembus discusses the known family trees of some of the students that attended the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Janice Canaday, Colonial Williamsburg Foundations African American community engagement manager, stands outside near the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

The classroom of the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Matthew Webster, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's executive director of architectural preservation and research, speaks about the Williamsburg Bray School's construction on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Matthew Webster shows an original rail from the classroom of the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Janice Canaday, Colonial Williamsburg Foundations African American community engagement manager, in the classroom of the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Replicas of the books that students would have used at the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Katie McKinney speaks about the curriculum of the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Residue from the original plaster walls of the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Elizabeth Drembus, the genealogist at the Williamsburg Bray School Lab, speaks about her work on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Janice Canaday, Colonial Williamsburg Foundations African American community engagement manager, has traced her ancestors to the Williamsburg Bray School, on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

18th century nails shoved in between hand craved joints in the stairs leading up to the second floor of the Williamsburg Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

Katie McKinney, is the Margaret Beck Pritchard Associate curator of Maps and Prints for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

A dog's paw print (left of arrow) is seen in one of the chimney bricks at the Bray School on Wednesday, Oct 30, 2024 in Williamsburg, Va. (AP Photo/John C. Clark)

WASHINGTON (AP) — Next week's presidential election isn't just a referendum on Donald Trump and Kamala Harris. It's also a measure of the influence the world's richest man wields over American democracy.

Elon Musk, the South African-born tech and business titan, has spent at least $119 million mobilizing Trump's supporters to back the Republican nominee. His social media platform, X, has become a firehose of pro-Trump propaganda. And he's playing a starring role in Trump-style rallies in critical battleground states.

All the while, he's coming under growing scrutiny. He skipped a hearing on Thursday in a lawsuit over his effort to dole out millions of dollars to registered voters, giveaways legal experts liken to vote buying. He’s being investigated by the Securities and Exchange Commission. And The Wall Street Journal recently reported that Musk regularly communicates with Russian President Vladimir Putin, a potential national security risk because SpaceX, his aerospace company, holds billions of dollars worth of contracts with NASA and the Department of Defense.

Musk is hardly the only person whose megawealth places him at the nexus of politics, business and foreign policy. But few are working so publicly for a single candidate as Musk, whose expansive business ties and growing bravado pose a vexing test of one unelected person's political power. His stature is perhaps one of the most tangible consequences of the Supreme Court's 2010 Citizens United decision, which eliminated many limits on political giving.

“This is definitely an election brought to you by Citizens United,” said Daniel I. Weiner, the director of elections and government at the Brennan Center for Justice, who added that the phenomenon was bigger that just Musk. “What this is really about is a transformation of our campaign finance system to one in which the wealthiest donors are playing a central role.”

Musk did not respond to a request for comment made through his attorney. Tesla, his electric car company, and X did not respond to inquiries. SpaceX disputed parts of The Journal's reporting in a statement and said it continues to work in “close partnership with the U.S. Government.”

Musk’s conversion to a self-described “Dark MAGA” Trump warrior is a recent one. In the past, he donated modest sums to both Republicans and Democrats, including $5,000 to Hillary Clinton in 2016, records show. He didn’t contribute to Trump’s political efforts until this year, according to federal campaign finance disclosures.

He was all in once he did.

Musk is now leading America PAC, a super political action committee that is spearheading Trump’s get-out-the-vote effort.

As a newcomer to politics, there have been growing pains.

Over the summer, America PAC struggled to reach its voter contact goals. Musk brought in a new team of political consultants, Generra Peck and Phil Cox, who worked on Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis ’ losing Republican presidential primary bid.

On paper, the numbers have improved. But Republican officials, operatives and activists say in some critical places it’s been difficult to tell how active the PAC’s ground effort has been.

The PAC's presence is not perceptible in rural Georgia, according to three Republican strategists who are closely monitoring the ground game in the battleground state. For example, America PAC has shown little evidence of leaving literature behind on doorsteps, as is common when a voter is not home, especially in remote places, the three people said.

There are also indicators Musk, a tech innovator, has been taken advantage of at his own game. In Nevada, three other people familiar with America PAC’s efforts said hired canvassers paid tech-savvy operatives to digitally manipulate an app used to track their progress — appearing to falsify their data so they could get paid for work that they did not do. Canvassers are typically paid by the number of doors that they knock on.

There are signs the practice wasn't limited to Nevada. One person warned America PAC leadership weeks ago that canvasing data from multiple states showed signs that it had been falsified, but their concerns were not acted on, according to two people with knowledge of the matter.

The individuals, like others who provided details about Musk’s political operation, insisted on anonymity to discuss the matter out of fear of retribution.

Musk has become frustrated with the inner workings of his political organization and has brought in private sector associates, including Steve Davis, president of the Boring company, Musk’s tunnel building company, according to three people with knowledge of the move. Davis’ role with America PAC was previously reported by The New York Times.

A person close to the PAC disputed that the group had been taken advantage of, suggesting it was a conspiracy theory based on a poor understanding of how political canvassing works. The person insisted on anonymity because they were not authorized to publicly discuss the innerworkings of the PAC.

Musk’s leadership of the PAC has not been his only political stumble.

On Monday, Philadelphia’s district attorney filed a lawsuit to halt Musk’s $1 million cash sweepstakes, which is a part of America PAC’s effort to garner support for Trump. Musk had pledged to give away $1 million a day until the election to voters in battleground states who have signed a petition supporting the Constitution. Legal experts cautioned that the contest was likely illegal, venturing into vote buying territory because participants were required to be registered to vote to win the money.

Democratic District Attorney Larry Krasner’s suit argues the giveaways amount to an illegal lottery. A state judge put the case on hold on Thursday while a federal court considers taking action. The Department of Justice sent a warning letter to America PAC that the giveaways could violate election law.

Musk has more riding on the election than just bragging rights.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the main agency that regulates Tesla, has repeatedly proved to be a thorn for the electric car maker run by Musk, which is the primary source of his wealth. The agency is overseeing more than a dozen recalls, some that Tesla resisted. It has also opened investigations that have raised doubts about Musk’s claims that Tesla is close to deploying self-driving vehicles, a key expectation of shareholders and a major driver of Tesla’s lofty share price.

Earlier this year Tesla disclosed that the Department of Justice and the SEC have requested and subpoenaed information about “Full Self-Driving” capability, vehicle functionality, data privacy and other matters.

The social media platform X is another Musk company that has drawn interest of the Biden administration. The Federal Trade Commission has probed Musk’s handling of sensitive consumer data after he took control of the company in 2022 but has not brought enforcement action. The SEC has an ongoing investigation of Musk’s purchase of the social media company.

Musk has been forceful with his political views on the platform, changing its rules, content moderation systems and algorithms to conform with his world view. After Musk endorsed Trump following an attempt on the former president’s life last summer, the platform has transformed into a megaphone for Trump’s campaign, offering an unprecedented level of free advertising that is all but impossible to calculate the value of.

Many of his troubles, which Musk blames President Joe Biden and Democrats for, could go away if Trump is elected. The former president has mused that Musk could have a formal role in a future Trump administration that focuses on government efficiency — an enormous conflict of interest given Musk’s companies' vast dealings with the government.

Musk has even offered to help develop national safety standards for self-driving vehicles, alarming auto safety groups, which also worry that he could interfere with investigations of Tesla.

“Of course the fox wants to build the henhouse,” said Michael Brooks, executive director of the nonprofit Center for Auto Safety watchdog group.

That’s also what makes the revelation that Musk has been in regular contact with Putin so troubling to foreign policy experts. The Defense Department and NASA are heavily dependent on SpaceX to launch spy satellites and take astronauts into space. But The Wall Street Journal reported that during one talk, Putin asked Musk not to activate his Starlink satellite system, a subsidiary of SpaceX, over Taiwan as a favor for Chinese President Xi Jinping. Russia has denied that the conversation took place.

In a statement posted to X, the aerospace company said the Journal story included “long-ago debunked claims” and questioned the relevance of the newspaper's reporting on Taiwan.

“Starlink is not available there because Taiwan has not given us a license to operate,” the statement read. “This has nothing to do with Russia or China.”

National security experts say the revelation that Musk communicated with Putin is still troubling.

Putin is "a war criminal who is slaughtering civilians. That makes this wrong in my view,” former U.S. Ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul told The Associated Press last week. “You have to decide what team you are on. Are you on the American team or are you on the Russian team?”

Beaumont reported from Des Moines, Iowa, and Krisher reported from Detroit. Associated Press writers Alan Suderman in Richmond, Virginia, Barbara Ortutay in San Francisco and Mike Catalini in Morrisville, Pennsylvania, contributed to this report.

Elon Musk speaks at Life Center Church in Harrisburg, Pa., Saturday, Oct. 19, 2024. (Sean Simmers/The Patriot-News via AP)

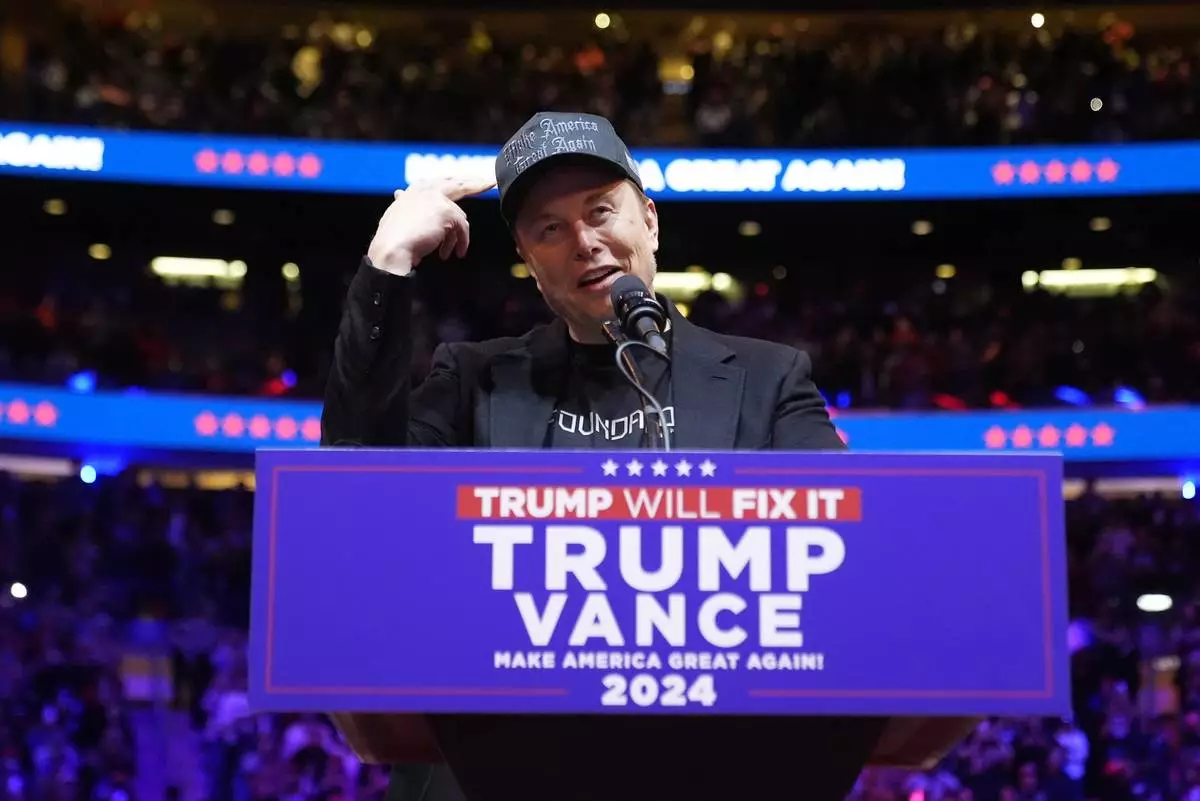

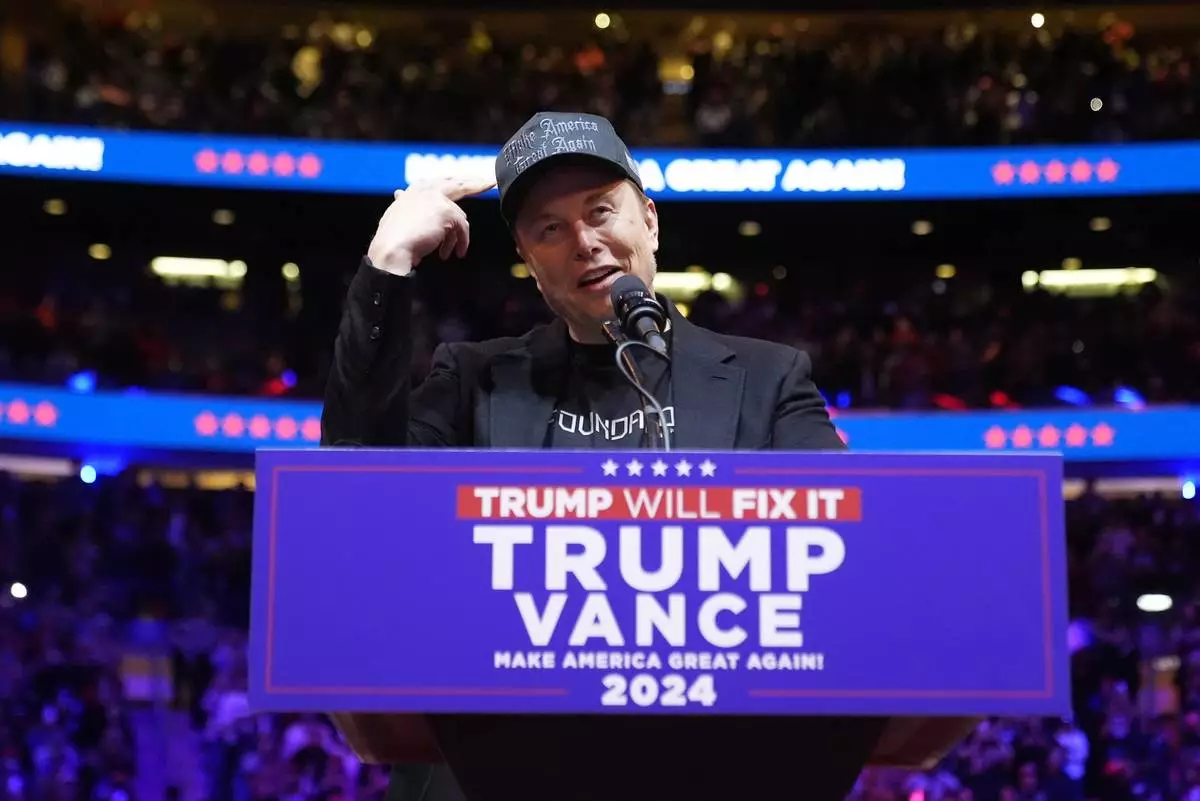

Elon Musk speaks before Republican presidential nominee former President Donald Trump at a campaign rally at Madison Square Garden, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

FILE - Elon Musk speaks before Republican presidential nominee former President Donald Trump at a campaign rally at Madison Square Garden, Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024, in New York. (AP Photo/Evan Vucci, File)