BARCELONA, Spain (AP) — A Spanish research vessel that investigates marine ecosystems has been abruptly diverted from its usual task to take on a new job: Helping in the increasingly desperate search for the missing from Spain’s floods.

The 24 crew members aboard the Ramón Margalef were preparing Friday to use its sensors and submersible robot to map an offshore area of 36 square kilometers — the equivalent of more than 5,000 soccer fields — to see if they can locate vehicles that last week's catastrophic floods swept into the Mediterranean Sea.

Click to Gallery

Members of a theatre company sit with their muddy belongings after the floods in the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

A house affected by flooding is photographed in Massanassa, Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. The graffiti in Spanish means 'Mazon dimisión' in reference to the president of the Valencia community Carlos Mazon. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Members of the V battalion of the military emergency unit, UME, use a canoe to search the area for bodies washed away by the floods in the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

A volunteer walks with a broom over a muddy street in Massanassa, Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Civil Guards walk in a flooded indoor car park to check cars for bodies after floods in Paiporta, near Valencia, Spain, Monday, Nov. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Alberto Saiz)

A soldier from the Spanish Parachute Squadron (EZAPAC) launches a drone in the search for bodies after floods in Barranco del Poyo on the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Tuesday, Nov. 5, 2024. (AP Photo/Alberto Saiz)

A soldier from the Spanish Parachute Squadron (EZAPAC) searches for bodies after floods in Barranco del Poyo on the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Tuesday, Nov. 5, 2024. (AP Photo/Alberto Saiz)

A soldier from the Spanish Parachute Squadron (EZAPAC) operates a drone in the search for bodies after floods in Barranco del Poyo on the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Tuesday, Nov. 5, 2024. (AP Photo/Alberto Saiz)

Soldiers from the Spanish Parachute Squadron (EZAPAC) look for bodies after floods in Barranco del Poyo, Spain, Tuesday, Nov. 5, 2024. (AP Photo/Alberto Saiz)

Members of the army, police and volunteers clean the mud after the floods, in Masanasa, Valencia, Spain, Thursday, Nov. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Members of the army and police walk through streets still awash with mud while clearing debris and cleaning up after the floods in Masanasa, Valencia, Spain, Thursday, Nov. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Dolores Merchan, 67, looks down on her mud-splattered belongings from the house where she has lived all her life with her husband and three children, and which has been severely affected by the floods in Masanasa, Valencia, Spain, Thursday, Nov. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Members of the V battalion of the military emergency unit, UME, search the area for bodies washed away by the floods in the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Members of the V battalion of the military emergency unit, UME, search the area for bodies washed away by the floods in the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Members of the fire brigade search the area for bodies washed away by the floods in the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Members of the V battalion of the military emergency unit, UME, use a canoe to search the area for bodies washed away by the floods in the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

The hope is that a map of sunken vehicles could lead to the recovery of bodies. Nearly 100 people have been officially declared missing, and authorities admit that is likely more people are unaccounted for, in addition to more than 200 declared dead.

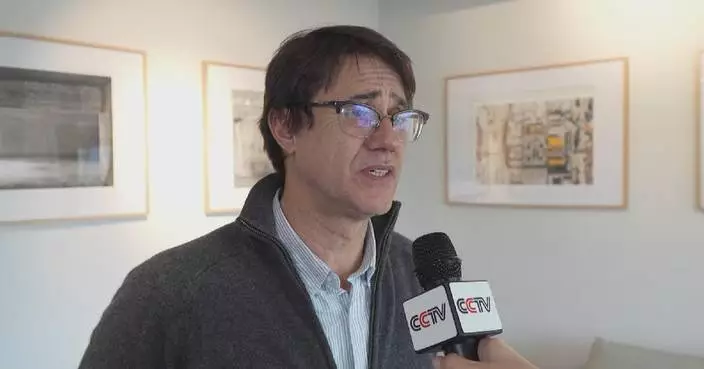

Pablo Carrera, the marine biologist leading the mission, estimates that in 10 days his team will be able to hand over useful information to police and emergency services. Without a map, he said, it would be practically impossible for police to carry out an effective and systematic recovery operation to reach vehicles that ended up on the seabed.

“It would be like finding a needle in a haystack," Carrera told The Associated Press by phone.

Many cars became death traps when the tsunami-like flooding hit on Oct. 29.

The boat will join a wider effort by police and soldiers who have expanded their searches for bodies and the missing beyond the devastated towns and streets. Searchers have used poles to probe into layers of mud while sniffer dogs tried to find scent traces of bodies buried in canal banks and fields. They are also looking at beaches that line the coast.

The first area the Ramón Margalef is searching is the stretch of sea off the Albufera wetlands, where at least some of the water ended up after ripping through villages and the southern outskirts of Valencia city.

Spanish state broadcaster said Friday that the body of one woman had been found on the beach after she went missing when the rushing water swept through her town of Pedralba, roughly an hour’s drive from the coast.

Carrera, 60, is head of the fleet of the research vessels run by the Spanish Institute of Oceanography, a government-funded science center under the umbrella of the Spanish National Research Council.

He boarded the Ramón Margalef in Alicante, located on Spain's south coast, from where it will set sail to reach Valencia’s waters before dawn Saturday. The plan is to go straight to work with the 10 scientists and technicians and 14 sailors working non-stop in shifts. The boat also helped research the impact from the lava flow that reached the sea from the 2021 La Palma volcano eruption in Spain's Canary Islands.

Finding a body at sea, Carrera said, is highly unlikely. So the focus is on large objects that shouldn't be there.

The boat’s submersible robot loaded with cameras can dive to a depth of 60 meters to attempt to identify cars. Ideally, they will try to locate license plates, although visibility could be extremely limited and the cars could be smashed to bits or engulfed in the muck, Carrera said.

In the longer term, he said his team will also evaluate the impact of the flood runoff on the marine ecosystem.

Those findings will contribute to initiatives by other Spanish research centers to study Spain's deadliest floods of the century.

Spain is used to the occasional deadly flood produced by autumn storms. But the drought that has hit the country for the past two years and record hot temperatures helped magnify these floods, scientists say.

Spain’s meteorological agency said that the 30.4 inches of rain that fell in one hour in the Valencian town of Turis is an all-time national record.

“We have never seen an autumn storm of this intensity,” Carrera said. “We cannot stop climate change, so we have to prepare for its effects.”

Members of a theatre company sit with their muddy belongings after the floods in the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

A house affected by flooding is photographed in Massanassa, Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. The graffiti in Spanish means 'Mazon dimisión' in reference to the president of the Valencia community Carlos Mazon. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Members of the V battalion of the military emergency unit, UME, use a canoe to search the area for bodies washed away by the floods in the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

A volunteer walks with a broom over a muddy street in Massanassa, Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Civil Guards walk in a flooded indoor car park to check cars for bodies after floods in Paiporta, near Valencia, Spain, Monday, Nov. 4, 2024. (AP Photo/Alberto Saiz)

A soldier from the Spanish Parachute Squadron (EZAPAC) launches a drone in the search for bodies after floods in Barranco del Poyo on the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Tuesday, Nov. 5, 2024. (AP Photo/Alberto Saiz)

A soldier from the Spanish Parachute Squadron (EZAPAC) searches for bodies after floods in Barranco del Poyo on the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Tuesday, Nov. 5, 2024. (AP Photo/Alberto Saiz)

A soldier from the Spanish Parachute Squadron (EZAPAC) operates a drone in the search for bodies after floods in Barranco del Poyo on the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Tuesday, Nov. 5, 2024. (AP Photo/Alberto Saiz)

Soldiers from the Spanish Parachute Squadron (EZAPAC) look for bodies after floods in Barranco del Poyo, Spain, Tuesday, Nov. 5, 2024. (AP Photo/Alberto Saiz)

Members of the army, police and volunteers clean the mud after the floods, in Masanasa, Valencia, Spain, Thursday, Nov. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Members of the army and police walk through streets still awash with mud while clearing debris and cleaning up after the floods in Masanasa, Valencia, Spain, Thursday, Nov. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Dolores Merchan, 67, looks down on her mud-splattered belongings from the house where she has lived all her life with her husband and three children, and which has been severely affected by the floods in Masanasa, Valencia, Spain, Thursday, Nov. 7, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Members of the V battalion of the military emergency unit, UME, search the area for bodies washed away by the floods in the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Members of the V battalion of the military emergency unit, UME, search the area for bodies washed away by the floods in the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Members of the fire brigade search the area for bodies washed away by the floods in the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Members of the V battalion of the military emergency unit, UME, use a canoe to search the area for bodies washed away by the floods in the outskirts of Valencia, Spain, Friday, Nov. 8, 2024. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu will meet President Donald Trump in Washington on Monday, becoming the first foreign leader to visit Trump since he unleashed tariffs on countries around the world.

Whether Netanyahu’s visit succeeds in bringing down or eliminating Israel’s tariffs remains to be seen, but how it plays out could set the stage for how other world leaders try to address the new tariffs.

Here's the latest:

The confusion — which was amplified on social media and by some traditional media outlets — lasted less than a half hour but reflected a jittery mood on Wall Street as stocks plunged over worries that Trump’s tariffs could torpedo the global economy.

The origin of the false report was unclear but it appeared to be a misinterpretation of comments made by Kevin Hassett, director of the White House National Economic Council, during a Fox News interview Monday morning. Asked whether Trump would consider a 90-day tariff pause suggested by a prominent hedge fund manager, Hassett said “I think the president is going to decide what the president is going to decide.”

Nearly two hours later, multiple user accounts on social media platform X posted identical messages claiming Hassett said Trump is considering a pause for all countries except China.

The White House initially appeared as confused as everyone else. But after 20 minutes, a government account rejected the report as “fake news.”

▶ Read more about how the bogus report affected the markets

Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba in a 25 minute call with Trump on Monday raised concerns that the tariffs by the U.S. could weaken investment capacity among Japanese companies.

“The recent tariff measures by the United States are extremely regrettable,” Ishiba told reporters following the call. “I told the president that Japan has been the world’s largest investor in the U.S. for five consecutive years, and I also strongly expressed concern that the U.S. tariffs will reduce the investment capacity of Japanese companies.”

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops says it’s ending a half-century of partnerships with the federal government to serve refugees and children, saying the “heartbreaking” decision follows the Trump administration’s abrupt halt to funding for refugee resettlement.

The break will inevitably result in fewer services than what Catholic agencies were able to offer in the past to the needy, the bishops said.

“As a national effort, we simply cannot sustain the work on our own at current levels or in current form,” said Archbishop Timothy Broglio, president of the USCCB. “We will work to identify alternative means of support for the people the federal government has already admitted to these programs. We ask your prayers for the many staff and refugees impacted.”

The decision means the bishops won’t be renewing existing agreements with the federal government, the bishops said. The announcement didn’t say how long current agreements were scheduled to last.

▶ Read more about the U.S. bishops’ partnership with the government

Beijing has issued several strongly-worded rebukes to Trump’s tariffs, including one entirely in the words of late-President Ronald Reagan.

“High tariffs inevitably lead to retaliation by foreign countries and the triggering of fierce trade wars,” the Republican president said in a video clip dated 1987, as posted on the X social media site Monday by the Chinese Embassy in the U.S. The embassy wrote that the decades-old speech “finds new relevance in 2025.”

“The result is more and more tariffs, higher and higher trader barriers, and less and less competition,” Reagan said in the speech, in which he warned of the worst from tariff wars: markets should collapse, businesses shut down, and millions of people lose jobs.

Trump greeted the Israeli prime minister with the firm handshake as he arrived for talks.

Trump ignored shouted questions from reporters about the tumbling global markets and whether he would lift tariffs on Israel.

Family and friends of the first Black Republican woman elected to Congress gathered in Salt Lake City on Monday to honor her life. Love died of brain cancer at age 49.

Hundreds of mourners attended the service at the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints Institute of Religion at the University of Utah.

Love’s sister Cyndi Brito shared childhood memories, including how Love used to rehearse all day and night for starring roles in her school plays.

“Sis, we will always, always look up to you,” Brito said. “Keep being the best.”

The former lawmaker had undergone treatment for an aggressive brain tumor called glioblastoma. She died at her home in Saratoga Springs, Utah, weeks after her daughter announced she was no longer responding to treatment.

Love, born Ludmya Bourdeau, represented Utah on Capitol Hill from 2015 to 2019.

The White House did not offer any immediate explanation for why the news conference was canceled, but Trump and Netanyahu were expected to make comments to reporters at the start of their scheduled Oval Office meeting.

President Trump threatened to raise the tariffs if Beijing doesn’t withdraw its retaliatory tariffs.

“At this point, it is extremely unlikely for China to back down,” said Yun Sun, director of the China program at the Washington-based think tank Stimson Center, adding any leadership summit between Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping “doesn’t appear likely in the near future.”

“China is increasingly convinced that the tariff is not negotiable because Trump’s eventual goal is to bring manufacturing jobs back to the U.S.,” Sun said.

Craig Singleton, senior China fellow at another Washington-based think tank Foundation for Defense of Democracies, called Trump’s threat Monday “a blunt ultimatum to Beijing that sharply raises the takes in the U.S.-China tariff war.” He said Beijing’s rigid system and fear of looking weak prevent Xi from opening back channels with the Trump administration that could offer relief.

A member of Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency team has terminated some of the last remaining life-saving programs for refugees and others in the Middle East, two U.S. and U.N. officials tell The Associated Press.

The AP viewed some of the new contract termination notices, sent late last week by Jeremy Lewin, a DOGE associate now overseeing the dismantling of USAID. A USAID official and an official with the U.N. spoke to the AP on condition of anonymity because they weren’t authorized to speak.

The move severs U.S. funding for some key projects by the World Food Program, the world’s largest provider of food aid. Another notice viewed by the AP terminated funding for sending Afghan women overseas for education. An administrator for the program, which is a project of Texas A & M University, said the women would now face return to Afghanistan, where their lives may be in danger from the Taliban. That administrator also spoke on condition of anonymity because that person wasn’t authorized to speak.

— Ellen Knickmeyer and Sam Magdy

The Monday visit was to congratulate the baseball team for winning the World Series last season.

Trump singled out several Los Angeles Dodgers for their achievements last season, praising Ohtani for becoming baseball’s first 50/50 player, Japanese pitcher Yoshi Yamamoto and NL Championship Series MVP Tommy Edman.

Trump praised Betts for his play — and took a dig at the Boston Red Sox for trading him to the Dodgers — and they shook hands at the ceremony.

Trump also boasted that egg prices have dropped “73%” on his watch and he refused to introduce some senators at the ceremony, because “I just don’t particularly like them, so I won’t introduce (them).”

Trump campaigned last year in opposition of the deal, saying a Japanese company’s acquisition of the company would hurt American manufacturing. But shortly after becoming president, Trump said he’d reached an agreement for Nippon Steel to instead invest in U.S. Steel without providing details.

The directive signed Monday by Trump would give the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, CFIUS, 45 days to review the proposed purchase.

It raises fresh concerns that Trump’s drive to rebalance the global economy could lead to a trade war.

The threat, which Trump delivered Monday on social media, came after China said it would retaliate against U.S. tariffs announced last week.

“If China does not withdraw its 34% increase above their already long term trading abuses by tomorrow, April 8th, 2025, the United States will impose ADDITIONAL Tariffs on China of 50%, effective April 9th,” he wrote on Truth Social. “Additionally, all talks with China concerning their requested meetings with us will be terminated!”

Trump has remained defiant as the stock market continued plunging and fears of a recession grew.

▶ Read more about Trump’s tariffs

The Trump administration has notified the World Food Program and other partners that it’s terminated some of the last remaining lifesaving humanitarian programs across the Middle East, a U.S. and U.N. official told The Associated Press.

An official with USAID says about 60 letters canceling contracts were sent over the past week, including to the World Food Program.

An official with the United Nations says WFP received termination letters for Lebanon, Jordan and Syria.

The USAID official says U.S. funding for key programs in Yemen, Somalia, Afghanistan and Zimbabwe also were affected, including those providing food, water, medical care and shelter for people displaced by war.

▶ Read more about the canceled USAID contracts

— Ellen Knickmeyer and Sam Magdy

The Justice Department argued in an emergency appeal to the justices that U.S. District Judge Paula Xinis overstepped her authority when she ordered Kilmar Abrego Garcia returned to the United States.

Abrego Garcia is no longer in U.S. custody and the government has no way to get him back, the administration argued.

Xinis gave the administration until just before midnight Tuesday to “facilitate and effectuate” Abrego Garcia’s return.

The federal appeals court in Richmond, Virginia, denied the administration’s request for a stay.

▶ Read more about Kilmar Abrego Garcia’s deportation

Wilmer Escaray left Venezuela in 2007 and enrolled at Miami Dade College, opening his first restaurant six years later.

Today, he has a dozen businesses that hire Venezuelan migrants like he once was, workers who are now terrified by what could be the end of their legal shield from deportation.

Since the start of February, the Trump administration has ended two federal programs that together allowed more 700,000 Venezuelans to live and work legally in the U.S. along with hundreds of thousands of Cubans, Haitians and Nicaraguans.

In the largest Venezuelan community in the United States, people dread what could face them if lawsuits that aim to stop the government fail. It’s all anyone discusses in “Little Venezuela” or “Doralzuela,” a city of 80,000 people surrounded by Miami sprawl, freeways and the Florida Everglades.

▶ Read more about fears in Miami’s ‘Little Venezuela’

The Monday meeting will make Netanyahu the first foreign leader to visit Trump since he unleashed tariffs on countries around the world.

Whether Netanyahu’s visit succeeds in bringing down or eliminating Israel’s tariffs remains to be seen, but how it plays out could set the stage for how other world leaders try to address the new tariffs.

Netanyahu’s office has put the focus of his hastily organized Washington visit on the tariffs, while stressing that the two leaders will discuss major geopolitical issues including the war in Gaza, tensions with Iran, Israel-Turkey ties and the International Criminal Court, which issued an arrest warrant against the Israeli leader last year. Trump in February signed an executive order imposing sanctions on the ICC over its investigations of Israel.

▶ Read more about Trump’s meeting with Netanyahu

The stock market briefly spiked on a report that Kevin Hassett, a top White House economic adviser, said the president was considering a 90-day pause on tariffs.

The supposed remark from Hassett circulated on social media, but no one could pinpoint where it came from even as the market flashed from red to green.

Hassett had spoken to Fox News earlier in the morning, when he was asked about a potential pause. However, he was noncommittal.

“I think the president is going to decide what the president is going to decide,” he said.

▶ Read more updates on the financial markets

Vance’s mother, Beverly Aikins’ on Friday received a 10-year sobriety medallion in the Roosevelt Room at a ceremony with friends and family.

Vance described Aikins’ past drug addiction in his bestselling book “Hillbilly Elegy.”

The cases are likely headed to a Supreme Court showdown on the president’s power over independent agencies.

A divided U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit issued the ruling in the lawsuits separately brought by Merit Systems Protection Board member Cathy Harris and National Labor Relations Board member Gwynne Wilcox.

The ruling reverses, at least for now, a judgement from a three-judge panel from the same appellate court.

▶ Read more about Trump and the board members

The dispute over tariffs has caused some fracturing within Trump’s political coalition.

Hedge fund manager Bill Ackman said the president was “launching a global economic war against the whole world at once” and urged him to “call a time out.”

“We are heading for a self-induced, economic nuclear winter,” he wrote on X on Sunday.

Top White House economic adviser Kevin Hassett told Fox News on Monday morning that Ackman should “ease off the rhetoric a little bit.”

Hassett said critics were exaggerating the impact of trade disputes and talk of an “economic nuclear winter” was “completely irresponsible rhetoric.”

The president showed no interest in changing course despite turmoil in global markets.

He said other countries had been “taking advantage of the Good OL’ USA” on international trade.

“Our past ‘leaders’ are to blame for allowing this, and so much else, to happen to our Country,” he wrote on Truth Social. “MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN!”

Trump criticized China for increasing its own tariffs and “not acknowledging my warning for abusing countries not to retaliate.”

On a day when stock markets around the world dropped precipitously, Alabama Republican Party Chairman John Wahl led a celebration of the president whose global tariffs sparked the sell-off.

With no mention of the Wall Street roller coaster and global economic uncertainty, Wahl declared his state GOP’s “Trump Victory Dinner” — and the broader national moment — a triumph. And for anyone who rejects Trump, his agenda and the “America First” army that backs it all, Wahl had an offer: “The Alabama Republican Party will buy them a plane ticket to any country in the world they want to go to.”

Wahl’s audience — an assembly of lobbyists and donors, state lawmakers, local party officials and grassroots activists — laughed, applauded and sometimes roared throughout last week’s gala in downtown Birmingham.

Yet beyond the cheerleading, there were signs of a more cautious optimism and some worried whispers over Trump’s sweeping tariffs, the particulars of his deportation policy and the aggressive slashing by his Department of Government Efficiency.

▶ Read more about Trump’s support in Alabama

This morning, at 11 a.m., World Series Champions, the Los Angeles Dodgers, will visit the White House and meet the president. Later, at 1 p.m., Israel Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu will visit the White House and meet with Trump. At 2 p.m., Netanyahu and Trump will participate in a Bilateral Meeting in the Oval Office. At 2:30 p.m., they will hold a joint news conference.

Trump said Sunday that he won’t back down on his sweeping tariffs on imports from most of the world unless countries even out their trade with the U.S.

Speaking to reporters aboard Air Force One, Trump said he didn’t want global markets to fall, but also that he wasn’t concerned about the massive sell-off either, adding, “sometimes you have to take medicine to fix something.”

His comments came as global financial markets appeared on track to continue sharp declines once trading resumes Monday, and after Trump’s aides sought to soothe market concerns by saying more than 50 nations had reached out about launching negotiations to lift the tariffs.

The higher rates are set to be collected beginning Wednesday. Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said unfair trade practices are not “the kind of thing you can negotiate away in days or weeks.” The United States, he said, must see “what the countries offer and whether it’s believable.”

▶ Read more about the global impact of Trump’s tariffs

Pedestrian are reflected on a brokerage house's window as an electronic board displays shares trading index, in Beijing, Monday, April 7, 2025. (AP Photo/Andy Wong)

Shipping containers are stored at Bensenville intermodal terminal in Franklin Park, Ill., Sunday, April 6, 2025. (AP Photo/Nam Y. Huh)

President Donald Trump arrives at the White House on Marine One, Sunday, April 6, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Manuel Balce Ceneta)