WASHINGTON (AP) — One week after Election Day, control of the U.S. House rests on just over a dozen races where winners have not yet been determined.

Nine states have at least one uncalled House race, some of which are so close they are headed to a recount.

Click to Gallery

A sign directs the way to a polling place at Marina Park Community Center on Tuesday, Nov. 5, 2024, in Newport Beach, Calif. (AP Photo/Ashley Landis)

Election workers take down election signs as they close off the voting and drop off site at the Echo Park Recreation Center on Tuesday, Nov. 5, 2024, in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes)

Ballots are scanned and sorted at San Francisco Department of Elections in City Hall in San Francisco on Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2024. (Scott Strazzante/San Francisco Chronicle via AP)

Ballots are scanned and sorted at San Francisco Department of Elections in City Hall in San Francisco on Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2024. (Scott Strazzante/San Francisco Chronicle via AP)

Andrew Chen sorts ballots at San Francisco Department of Elections in City Hall in San Francisco on Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2024. (Scott Strazzante/San Francisco Chronicle via AP)

Then there’s California. About half of the yet-to-be-decided House races are in the state, which has only counted about three-quarters of its votes statewide.

This isn’t unusual or unexpected, as the nation’s most populous state is consistently among the slowest to report all its election results. Compare it to a state like Florida, the third-largest, which finished counting its votes four days after Election Day.

The same was true four years ago, when Florida reported the results of nearly 99% of ballots cast within a few hours of polls closing. In California, almost one-third of ballots were uncounted after election night, and the state was making almost daily updates to its count through Dec. 3, a full month after Election Day.

These differences in how states count — and how long it takes — exist because the Constitution sets out broad principles for electing a national government, but leaves the details to the states. The choices made by state lawmakers and election officials as they sort out those details affect everything from how voters cast a ballot to how quickly the tabulation and release of results takes place, how elections are kept secure and how officials maintain voters’ confidence in the process.

The gap between when California and Florida are able to finalize their count is the natural result of election officials in the two states choosing to emphasize different concerns and set different priorities. Here's a look at the differences:

Lawmakers in California designed their elections to improve accessibility and increase turnout. Whether it’s automatically receiving a ballot at home, having up until Election Day to turn it in or having several days to address any problems that may arise with their ballot, Californians have a lot of time and opportunity to vote. It comes at the expense of knowing the final vote counts soon after polls close.

“Our priority is trying to maximize participation of actively registered voters,” said Democratic Assemblymember Marc Berman, who authored the 2021 bill that permanently switched the state to all-mail elections. “What that means is things are a little slower. But in a society that wants immediate gratification, I think our democracy is worth taking a little time to get it right and to create a system where everyone can participate.”

California, which has long had a culture of voting absentee, started moving toward all-mail elections last decade. All-mail systems will almost always prolong the count. Mail ballots require additional verification steps — each must be opened individually, validated and processed — so they can take longer to tabulate than ballots cast in person that are then fed into a scanner at a neighborhood polling place.

In 2016, California passed a bill allowing counties to opt in to all-mail elections before instituting it statewide on a temporary basis in 2020 and enshrining it in law in time for the 2022 elections.

Studies found that the earliest states to institute all-mail elections – Oregon and Washington – saw higher turnout. Mail ballots also increase the likelihood of a voter casting a complete ballot, according to Melissa Michelson, a political scientist and dean at California’s Menlo College who has written on voter mobilization.

In recent years, the thousands of California voters who drop off their mail ballots on Election Day created a bottleneck on election night. In the past five general elections, California has tabulated an average of 38% of its vote after Election Day. Two years ago, in the 2022 midterm elections, half the state’s votes were counted after Election Day.

Slower counts have come alongside later mail ballot deadlines. In 2015, California implemented its first postmark deadline, meaning that the state can count mail ballots that arrive after Election Day as long as the Postal Service receives the ballot by Election Day. Berman said the postmark deadline allows the state to treat the mailbox as a drop box in order to avoid punishing voters who cast their ballots properly but are affected by postal delays.

Initially, the law said ballots that arrived within three days of the election would be considered cast in time. This year, ballots may arrive up to a week after Election Day, so California won’t know how many ballots have been cast until Nov. 12. This deadline means that California will be counting ballots at least through that week because ballots arriving up to that point might still be valid and be added to the count.

Florida’s election system is geared toward quick and efficient tabulation. Coming out of its disastrous 2000 presidential election, when the U.S. Supreme Court settled a recount dispute and George W. Bush was declared the winner in the state over Al Gore, the state moved to standardize its election systems and clean up its canvass, or the process of confirming votes cast and counted.

Republican Rep. Bill Posey, who as state senator was the sponsor of the Florida Election Reform Act of 2001, said the two goals of the law — to count all legal votes and to ensure voters are confident their votes are counted — were accomplished by mandating optical ballot scanners in every precinct. That “most significant” change means no more “hanging chads” in Florida. The scanners read and aggregate results from paper ballots, immediately spitting back any that contain mistakes.

Florida’s deadlines are set to avoid having ballots arrive any later than when officials press “go” on the tabulator machines. The state has a receipt deadline for its absentee ballots, which means ballots that do not arrive by 7 p.m. local time on Election Day are not counted, regardless of when they were mailed.

Michael T. Morley, a professor of election law at Florida State University College of Law, pointed out that Florida election officials may begin processing ballots, but not actually count them, before polls close. That helps speed up the process, especially compared with states that don’t allow officials to process mail ballots before Election Day.

“They can determine the validity of ballots, confirm they should be counted and run them through machines,” Morley said. “They just can’t press the tally button.”

Florida takes steps to avoid a protracted back-and-forth on potentially problematic ballots. At the precinct, optical scanners catch some problems, such as a voter selecting too many candidates, that can be fixed on-site. Also, any voter who’s returned a mail ballot with a mismatched or missing signature has until 5 p.m. two days after the election to submit an affidavit fixing it. California gives voters up to four weeks after the election to address such inconsistencies.

Read more about how U.S. elections work at Explaining Election 2024, a series from The Associated Press aimed at helping make sense of the American democracy. The AP receives support from several private foundations to enhance its explanatory coverage of elections and democracy. See more about AP’s democracy initiative here. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

A sign directs the way to a polling place at Marina Park Community Center on Tuesday, Nov. 5, 2024, in Newport Beach, Calif. (AP Photo/Ashley Landis)

Election workers take down election signs as they close off the voting and drop off site at the Echo Park Recreation Center on Tuesday, Nov. 5, 2024, in Los Angeles. (AP Photo/Damian Dovarganes)

Ballots are scanned and sorted at San Francisco Department of Elections in City Hall in San Francisco on Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2024. (Scott Strazzante/San Francisco Chronicle via AP)

Ballots are scanned and sorted at San Francisco Department of Elections in City Hall in San Francisco on Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2024. (Scott Strazzante/San Francisco Chronicle via AP)

Andrew Chen sorts ballots at San Francisco Department of Elections in City Hall in San Francisco on Wednesday, Nov. 6, 2024. (Scott Strazzante/San Francisco Chronicle via AP)

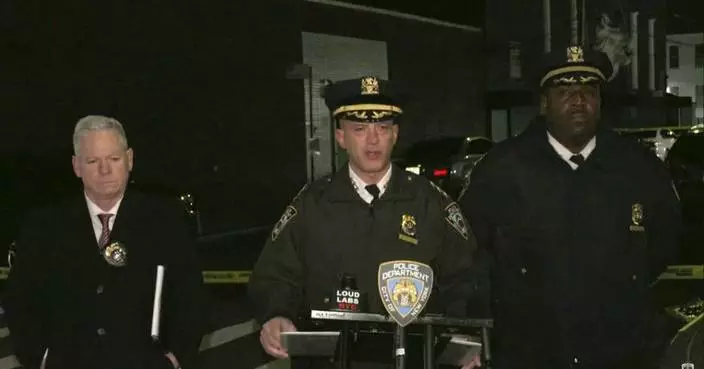

NEW ORLEANS (AP) — The U.S. Army veteran who drove a pickup truck into a crowd of New Year’s revelers acted alone, the FBI said Thursday, reversing its position from a day earlier that he likely worked with others in the deadly attack that officials said was inspired by the Islamic State group.

The FBI also revealed that the driver, Shamsud-Din Jabbar, a U.S. citizen from Texas, posted five videos on his Facebook account in the hours before the attack in which he proclaimed his support for the militant group and previewed the violence that he would soon unleash in the city's famed French Quarter district.

“This was an act of terrorism. It was premeditated and an evil act,” said Christopher Raia, the deputy assistant director of the FBI's counterterrorism division, calling Jabbar “100% inspired” by the Islamic State.

The attack killed 14 revelers, along with Jabbar, who was fatally shot in a firefight with police after steering his speeding truck around a barricade and plowing into the crowd.

It was the deadliest IS-inspired assault on U.S. soil in years, laying bare what federal officials have warned is a resurgent international terrorism threat. That threat is emerging as the FBI and other agencies brace for dramatic leadership upheaval after President-elect Donald Trump's administration takes office.

Seeking to assuage concerns about any broader plots, Raia stressed that there was no indication of a connection between the New Orleans attack and a Tesla Cybertruck explosion Wednesday outside Trump’s Las Vegas hotel.

The FBI continued to hunt for clues, but said that 24 hours into its investigation, it was now confident that the 42-year-old Jabbar was not aided by anyone else in the attack, which killed an 18-year-old aspiring nurse, a father of two and a former Princeton University football star.

Officials have reviewed surveillance video showing people standing near an improvised explosive device that Jabbar placed in a cooler along the city's Bourbon Street, where the attack occurred, but authorities “do not believe at this point these people are involved ... in any way,” Raia said.

Investigators were also trying to understand more about Jabbar's path to radicalization, which they say culminated with him picking up a rented truck in Houston on Dec. 30 and driving it to New Orleans the following night.

The FBI recovered a black Islamic State flag from his rented pickup and reviewed five videos posted to Facebook, including one in which he said he originally planned to harm his family and friends, but was concerned that news headlines would not focus on the “war between the believers and the disbelievers,” Raia said. He also left a last will and testament, the FBI said.

Jabbar joined the Army in 2007, serving on active duty in human resources and information technology and deploying to Afghanistan from 2009 to 2010, the service said. He transferred to the Army Reserve in 2015 and left in 2020 with the rank of staff sergeant.

Abdur-Rahim Jabbar, Jabbar's younger brother, told The Associated Press on Thursday that it “doesn’t feel real” that his brother could have done this.

“I never would have thought it’d be him,” he said. “It’s completely unlike him.”

He said that his brother had been isolated in the last few years, but that he had also been in touch with him and he didn’t see any signs of radicalization.

“It’s completely contradictory to who he was and how his family and his friends know him,” he said.

In New Orleans on Thursday, a still-reeling city inched back toward normal operations. Authorities finished processing the scene early in the morning, removing the last of the bodies, and Bourbon Street was set to reopen at some point later in the day, according to an official familiar with the matter who spoke on condition of anonymity to the AP.

The Sugar Bowl college football game between Notre Dame and Georgia, initially set for Wednesday night and postponed by a day in the interest of national security, was still on for Thursday. The city planned to host the Super Bowl next month.

“This is one of the safest places on earth," Louisiana Gov. Jeff Landry said. "It doesn’t mean that nothing can't happen.”

Tucker reported from Washington, and Mustian reported from Black Mountain, North Carolina. Associated Press reporters Stephen Smith, Chevel Johnson and Brett Martel in New Orleans; Jeff Martin in Atlanta; Alanna Durkin Richer, Tara Copp and Zeke Miller in Washington; Darlene Superville in New Castle, Delaware; Colleen Long in West Palm Beach, Florida; and Michael R. Sisak in New York contributed to this report.

Flowers are seen near where a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon streets, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

A man uses a power washer on Toulouse street a day after a vehicle was driven into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon streets, Thursday, Jan. 2, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Security with bomb sniffing dogs patrol the area around the Superdome ahead of the Sugar Bowl NCAA College Football Playoff game, Thursday, Jan. 2, 2025, in New Orleans. (AP Photo/Butch Dill)

Military personnel walk down Bourbon street, Thursday, Jan. 2, 2025 in New Orleans. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

People react at the intersection of Bourbon Street and Canal Street during the investigation after a pickup truck rammed into a crowd of revelers early on New Year's Day, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025, in New Orleans. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)

Police officers stand near the scene where a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon streets, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Matthias Hauswirth of New Orleans prays on the street near the scene where a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon streets, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

This undated passport photo provided by the FBI on Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025, shows Shamsud-Din Bahar Jabbar. (FBI via AP)

Emergency services attend the scene after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

The FBI investigates the area on Orleans St and Bourbon Street by St. Louis Cathedral in the French Quarter where a suspicious package was detonated after a person drove a truck into a crowd earlier on Bourbon Street on Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)

The FBI investigates the area on Orleans St and Bourbon Street by St. Louis Cathedral in the French Quarter where a suspicious package was detonated after a person drove a truck into a crowd earlier on Bourbon Street on Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)

A New Orleans police officer searches the area near a crime scene after a vehicle drove into a crowd on Canal and Bourbon Street earlier, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Jack Brook)

EDS NOTE: GRAPHIC CONTENT - Emergency personnel work the scene on Bourbon Street after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Investigators work the scene after a person drove a vehicle into a crowd killing several, earlier on Canal and Bourbon Street in New Orleans, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

New Orleans mayor LaToya Cantrell makes a statement after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

A mounted police officer arrives on Canal Street after a vehicle drove into a crowd earlier in New Orleans, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Kevin McGill)

A police barricade near the scene after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Emergency services attend the scene after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

The scene after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Emergency services attend the scene on Bourbon Street after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

The St. Louis Cathedral is seen on Orleans St is seen in the French Quarter where a suspicious package was detonated after a person drove a truck into a crowd earlier on Bourbon Street on Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)

Emergency services attend the scene on Bourbon Street after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Investigators work the scene after a person drove a vehicle into a crowd earlier on Canal and Bourbon Street in New Orleans, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Trevant Hayes, 20, sits in the French Quarter after the death of his friend, Nikyra Dedeaux, 18, after a pickup truck crashed into pedestrians on Bourbon Street followed by a shooting in the French Quarter in New Orleans, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)

A black flag with white lettering lies on the ground rolled up behind a pickup truck that a man drove into a crowd on Bourbon Street in New Orleans, killing and injuring a number of people, early Wednesday morning, Jan. 1, 2025. The FBI said they recovered an Islamic State group flag, which is black with white lettering, from the vehicle. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Emergency services attend the scene after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Security personnel gather at the scene on Bourbon Street after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

EDS NOTE: GRAPHIC CONTENT - Security personnel investigate the scene on Bourbon Street after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

The FBI investigates the area on Orleans St and Bourbon Street by St. Louis Cathedral in the French Quarter where a suspicious package was detonated after a person drove a truck into a crowd earlier on Bourbon Street on Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)

Edward Bruski, center, gets emotional at the scene where a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

FBI members examine the scene on Bourbon Street during the investigation of a truck fatally crashing into pedestrians on Bourbon Street in the French Quarter in New Orleans, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)

Emergency service vehicles form a security barrier to keep other vehicles out of the French Quarter after a vehicle drove into a crowd on New Orleans' Canal and Bourbon Street, Wednesday Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Gerald Herbert)

Members of the FBI walk around Bourbon Street during the investigation of a truck fatally crashing into pedestrians on Bourbon Street in the French Quarter in New Orleans, Wednesday, Jan. 1, 2025. (AP Photo/Matthew Hinton)