COLOMBO, Sri Lanka (AP) — The party of Sri Lanka’s new Marxist-leaning President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has won a majority in parliament, according to official election results Friday, providing a solid mandate for his program for economic revival.

Dissanayake’s National People’s Power Party won at least 123 of the 225 seats in parliament, according to partial results released by the Elections Commission.

Click to Gallery

Workers leave a poll counting center following the parliamentary election in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

People walk past polling results displayed on a giant screen outside a vote counting center following the parliamentary election in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

People watch polling results displayed on a giant screen outside a vote counting center following the parliamentary election in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

People queue up to cast their votes at a polling station during the parliamentary election in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024.(AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Polling workers return to a counting center with a ballot box at the end of the polling in the parliamentary election in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Sri Lankan President Anura Kumara Dissanayake leaves after casting his vote during the parliamentary election in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024.(AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

The Samagi Jana Balawegaya, or United People's Power Party, led by opposition leader Sajith Premedasa had 31 seats.

Dissanayake was elected president on Sept. 21 in a rejection of traditional political parties that have governed the island nation since its independence from British rule in 1948. But he received just 42% of the votes, fueling questions over his party’s outlook in Thursday’s parliamentary elections. But the party received large increases in support less than two months into his presidency.

In a major surprise and a big shift in the country's electoral landscape, his party won the Jaffna district, the heartland of ethnic Tamils in the north, and many other minority strongholds.

The victory in Jaffna marks a great dent for traditional ethnic Tamil parties that have dominated the politics of the north since independence.

It is also a major shift in the attitude of Tamils, who have long been suspicious of majority ethnic Sinhalese leaders. Ethnic Tamil rebels fought an unsuccessful civil war in 1983-2009 to create a separate homeland, saying they were being marginalized by governments controlled by Sinhalese.

According to conservative U.N. estimates, more than 100,000 people were killed in the conflict.

Veeragathy Thanabalasingham, a Colombo-based political analyst, said northern voters chose the NPP because they could not find a local alternative to traditional Tamil political parties, with which they were disillusioned.

“The Tamil parties were divided and contested separately, and as a result the Tamil people's representation is scattered,” he said.

Of the 225 seats in parliament, 196 were up for grabs under Sri Lanka’s proportional representative electoral system, which allocates seats in each district among the parties according to the proportion of the votes they get.

The remaining 29 seats — called the national list seats — are allocated to parties and independent groups according to the proportion of the total votes they receive countrywide.

The election comes at a decisive time for Sri Lankans, as the island nation is struggling to emerge from its worst economic crisis, having declared bankruptcy after defaulting on its external debt in 2022.

The country is now in the middle of a bailout program with the International Monetary Fund, with debt restructuring with international creditors nearly complete.

Dissanayake said during the presidential campaign that he planned to propose significant changes to the targets set in the IMF deal, which his predecessor, Ranil Wickremesinghe, signed, saying it placed too much burden on the people. However, he has since changed his stance and says Sri Lanka will go along with the agreement.

Sri Lanka’s crisis was largely the result of economic mismanagement combined with fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, which along with 2019 militant attacks devastated its important tourism industry. The pandemic also disrupted the flow of remittances from Sri Lankans working abroad.

The government also slashed taxes in 2019, depleting the treasury just as the virus hit. Foreign exchange reserves plummeted, leaving Sri Lanka unable to pay for imports or defend its currency, the rupee.

Sri Lanka’s economic upheaval led to a political crisis that forced then-President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to resign in 2022. Parliament then elected Wickremesinghe to replace him.,

The economy was stabilized, inflation dropped, the rupee strengthened and foreign reserves increased under Wickremesinghe. Nonetheless, he lost the election as public dissatisfaction grew over the government’s effort to increase revenue by raising electricity bills and imposing heavy new income taxes on professionals and businesses as part of the government’s efforts to meet the IMF conditions.

Voters were also drawn by the NPP’s cry for change in the political culture and an end to corruption, because they perceived the parties that ruled Sri Lanka so far caused the economic collapse.

Dissanayake’s promise to punish members of previous governments accused of corruption and to recover allegedly stolen assets also raised much hope among the people.

Jeewantha Balasuriya, 42, a businessman from the town of Gampaha, said he hopes Dissanayake and his party will use their resounding victory to rebuild the country.

“People have given them a strong mandate. I am hopeful that the NPP will use this mandate to uplift the country from the present pathetic situation,” he said.

He expressed confidence that Dissanayake and his party would curb corruption and mismanagement and establish law and order, which he said were vital for resuscitating the economy.

Workers leave a poll counting center following the parliamentary election in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

People walk past polling results displayed on a giant screen outside a vote counting center following the parliamentary election in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

People watch polling results displayed on a giant screen outside a vote counting center following the parliamentary election in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

People queue up to cast their votes at a polling station during the parliamentary election in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024.(AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Polling workers return to a counting center with a ballot box at the end of the polling in the parliamentary election in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

Sri Lankan President Anura Kumara Dissanayake leaves after casting his vote during the parliamentary election in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024.(AP Photo/Eranga Jayawardena)

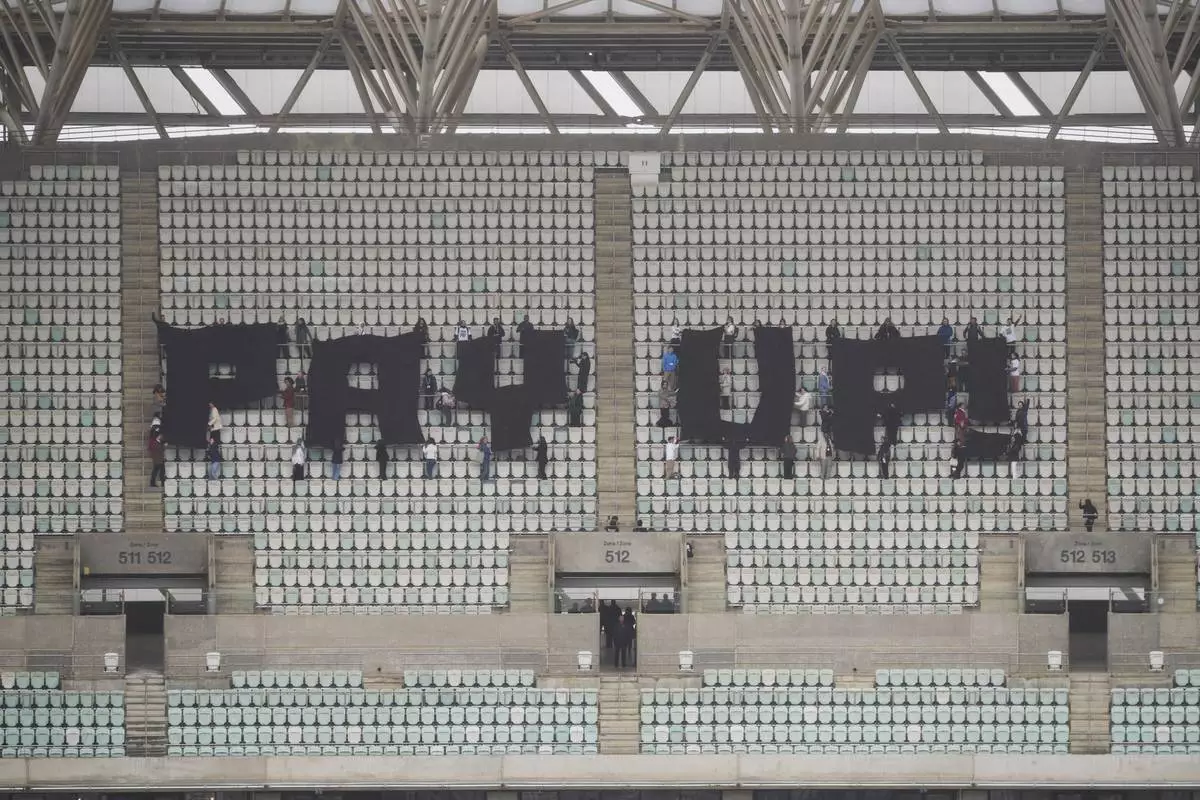

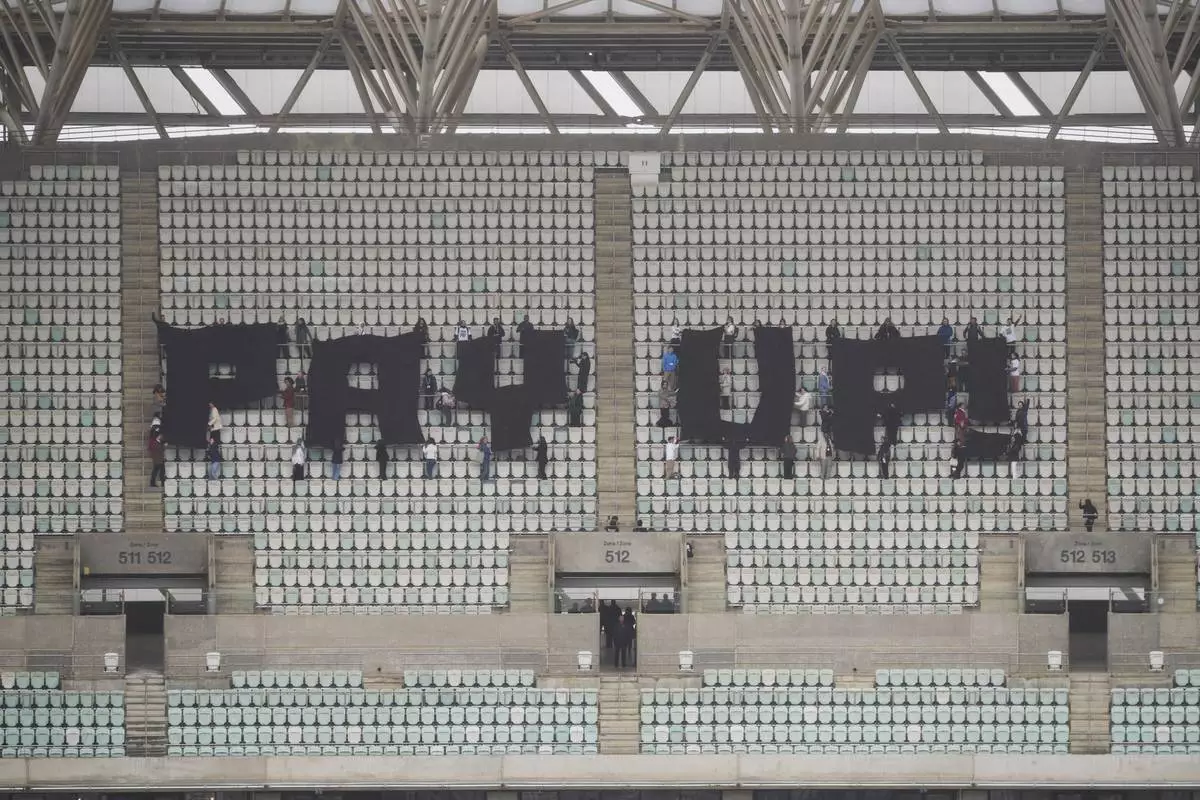

BAKU, Azerbaijan (AP) — In the nosebleed seats of a nearly-empty Baku Olympic stadium coated with a layer of dust, activists used a giant banner to beam the words “Pay Up” to the world.

The protest took weeks of thought and planning, but most of the attendees at this year's UN climate talks didn't see or hear it — except for maybe some in the COP29 presidency offices right below. The majority of the people involved in deciding the financial future of climate action at the talks remained in the sprawling venue, under white tarps with no windows.

It’s “really hard to make our demands heard,” said Bianca Castro, a climate activist from Portugal. She’s been to several COPs in the past and remembers years when there were thousands of protestors in the streets, and a multitude of strikes and actions throughout the event. But at the stadium's seats, they were told exactly where and when they could stand and chants were restricted. A United Nations climate change spokesperson said that the action was in a part of the venue that isn’t open to participants, and involved extensive dialogue among the participants, facility managers and health and safety officers.

Still, Castro said the difficulty of making an impact meant many are "losing hope in the in the process."

People involved in protests say they have felt a trend in recent years of stricter rules from the United Nations organizers with COPs being held in countries whose governments limit demonstrations and the participation of civil society. And some community spaces for prepping and organizing have had to resort to going underground because of security concerns. But the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change — who run the COPs — say the code of conduct that governs the conferences has not changed, nor has the way it's applied, and COP29 organizers say there's space across the venue for participants to “make their voices heard in line with the UNFCCC code of conduct and Azerbaijan law safely and without interference.”

Despite the challenges and what some see as a depressing mood, activists say it remains a critical time to speak up about the historical and present-day injustices that are in desperate need of money and attention.

It's especially true this year at a COP where the theme is finance, because voices from the Global South play a pivotal role in bringing ambitious demands to the negotiating table, said Rachitaa Gupta, who coordinates a global network of organizations advocating for climate justice. But she said that there have been more and more defamation rules each year that prohibit protestors from calling out specific countries or names.

“We do feel that the restrictions have reached a stage where it’s a constant battle on what we can say,” Gupta said. Activists can’t name specific countries, people or businesses in line with the UNFCCC’s code of conduct.

Meanwhile, across town in a downtown Baku building, activists paint, snip fabric and sculpt with cardboard and papier-mache in a quest for visually compelling symbols of climate action. The art space was once a place of community, where people came to pour their feelings into a creative outlet, said Amalen Sathananthar, coordinator at a collective called the Artivist Network. But now his team keeps the art space private and doesn't reveal its location because of security concerns.

Restrictions, though, can breed creativity among the artists designing the banners, flags and props that demonstrators use during protests. In the absence of naming specific people or countries, or carrying country flags, they instead have to come up with other imagery to get their messages across.

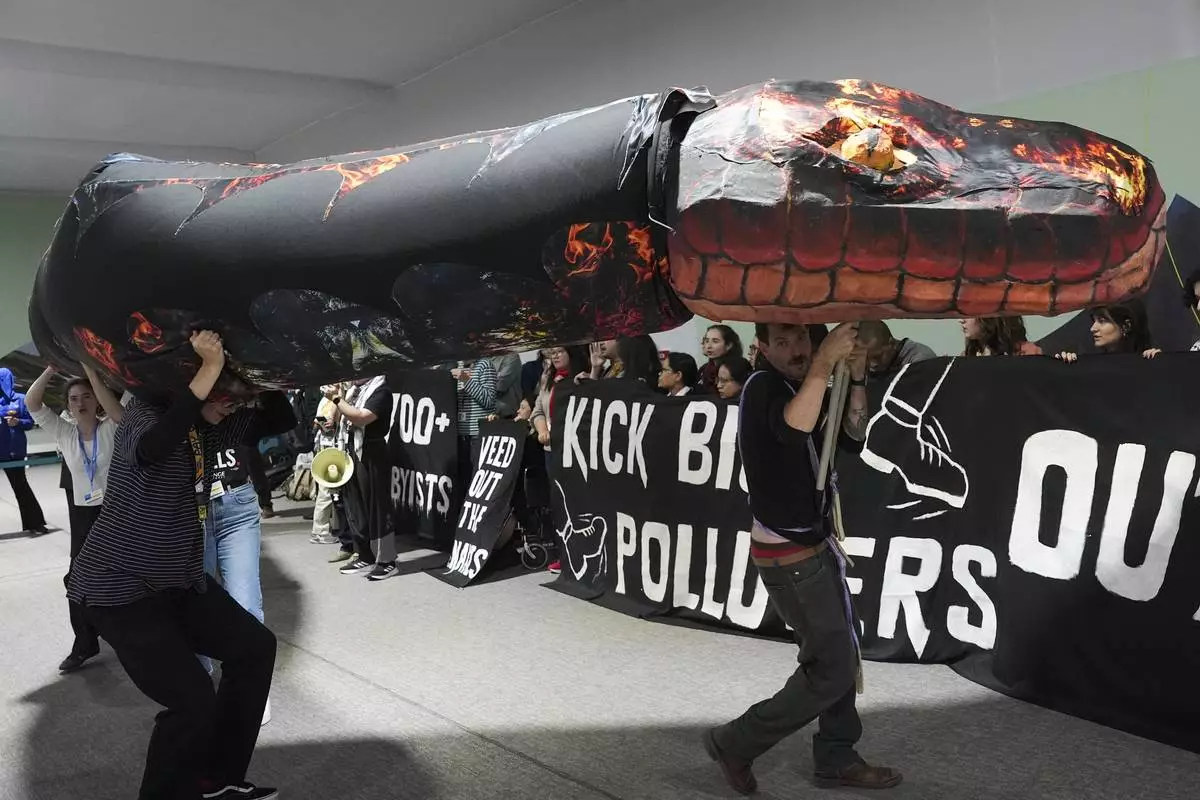

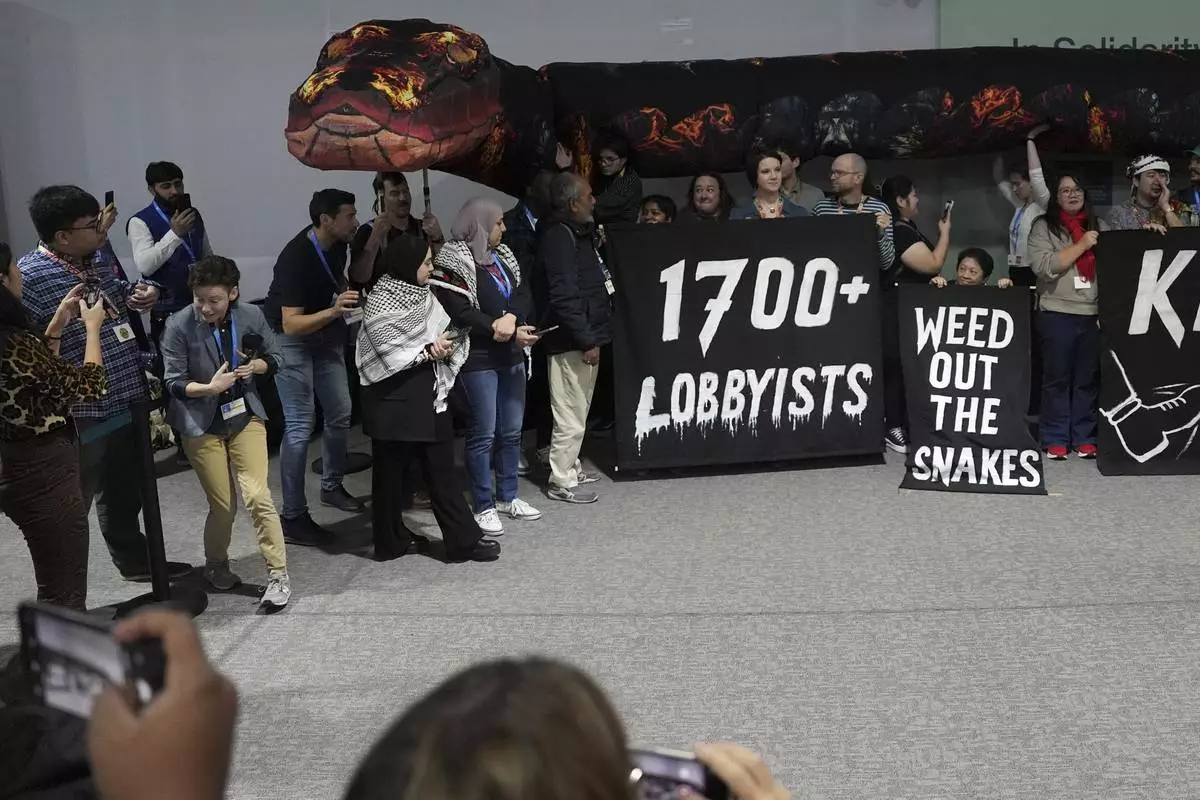

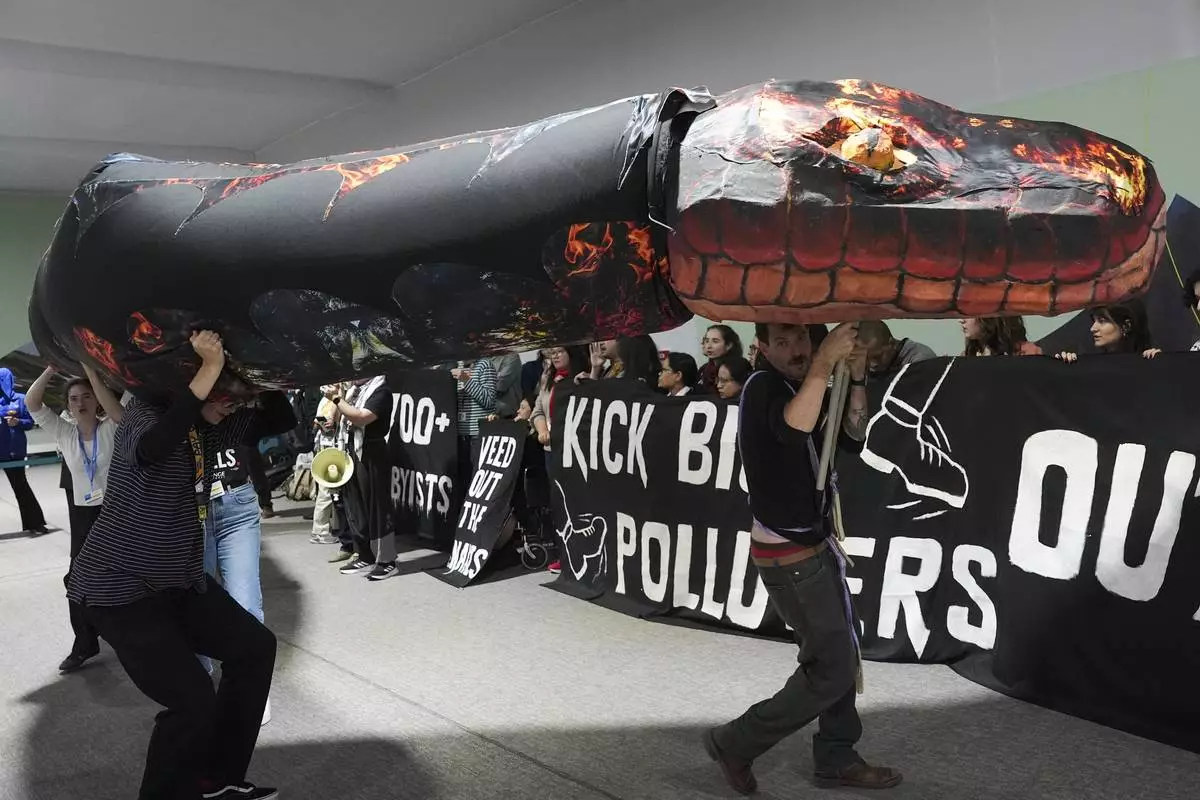

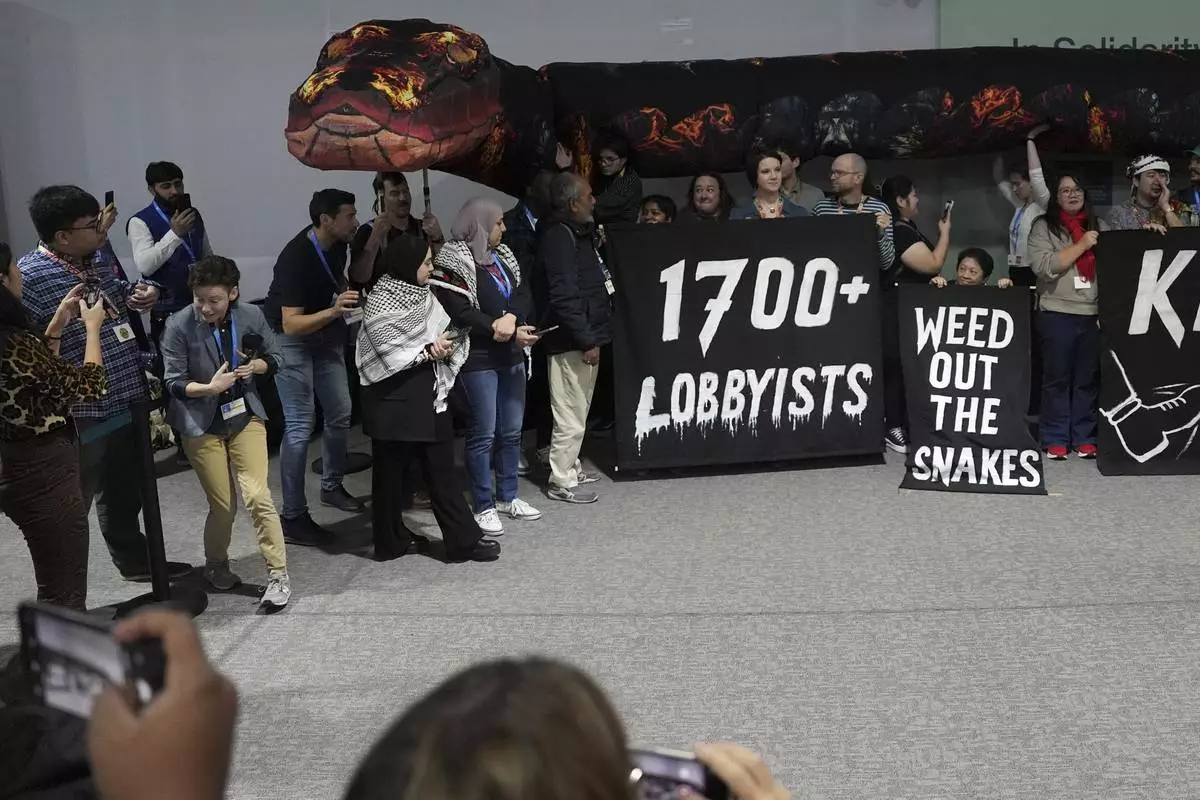

One of this year’s pieces was a larger-than-life snake for an action with the slogan “Weed Out the Snakes,” calling attention for the removal of big polluters and fossil fuel lobbyists at climate talks, something that's been “outrageous,” said Jax Bongon, whose organization is part of the Kick Big Polluters Out coalition. “Would you invite an arsonist to put out the fire?”

It's an issue that's "particularly hard for me as someone from the Philippines,” Bongon added, but called it "really uplifting" to watch the action come together despite challenges.

Demonstrators hoisted the fire-colored serpent with on their shoulders and heads. Together, their hisses filled the tent, bringing the snake to life.

“I think that the only reason people dare to do this is because, one, they're struggling on how to be heard,” said Dani Rupa, one of the artists working in Baku with The Artivist Network. “But, two, that there is like creative support for them to be able to do this.”

The Artivist Network have been doing this for a long time, attending COPs unofficially since the early 2000s and officially since they formalized in 2018. Sathananthar's seen the multitude of ways protestors have had to argue with host countries and the UNFCCC governing body to get space for activism. But this year, especially, he said it's a struggle — “negotiations within negotiations” that have had Sathananthar staying up late into the night in talks and on occasion have left him “fuming.”

A spokesperson for UNFCCC said they've “been a recognized global leader in ensuring safe civic spaces at COPs for many years" which normally doesn't happen at other intergovernmental events.

Still, activists feel that only being able to protest within certain areas throughout the venue — when previous years have seen mass street marches in host cities — can be frustrating.

“Every action you now have to fight for desperately," Sathananthar said. “We fought to get these spaces and we will fight to keep them."

Follow Melina Walling on X at @MelinaWalling. Follow Joshua A. Bickel on X and Instagram.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Dani Rupa, from Budapest, Hungary, paints a snake for a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Kevin Buckland, right, and other activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels called weed out the snakes at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Activists with signs spell out "pay up" for climate finance in the Baku Olympic Stadium during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Activists with signs spell out "pay up" for climate finance in the Baku Olympic Stadium during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Kevin Buckland, front, and other activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels called weed out the snakes at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Shaq Koyok, of Malaysia, paints a sign ahead of a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Anna Varszegi, of Budapest, Hungary, sketches out patterns during preparations for a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Dani Rupa, from Budapest, Hungary, paints a snake for a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels called weed out the snakes at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)