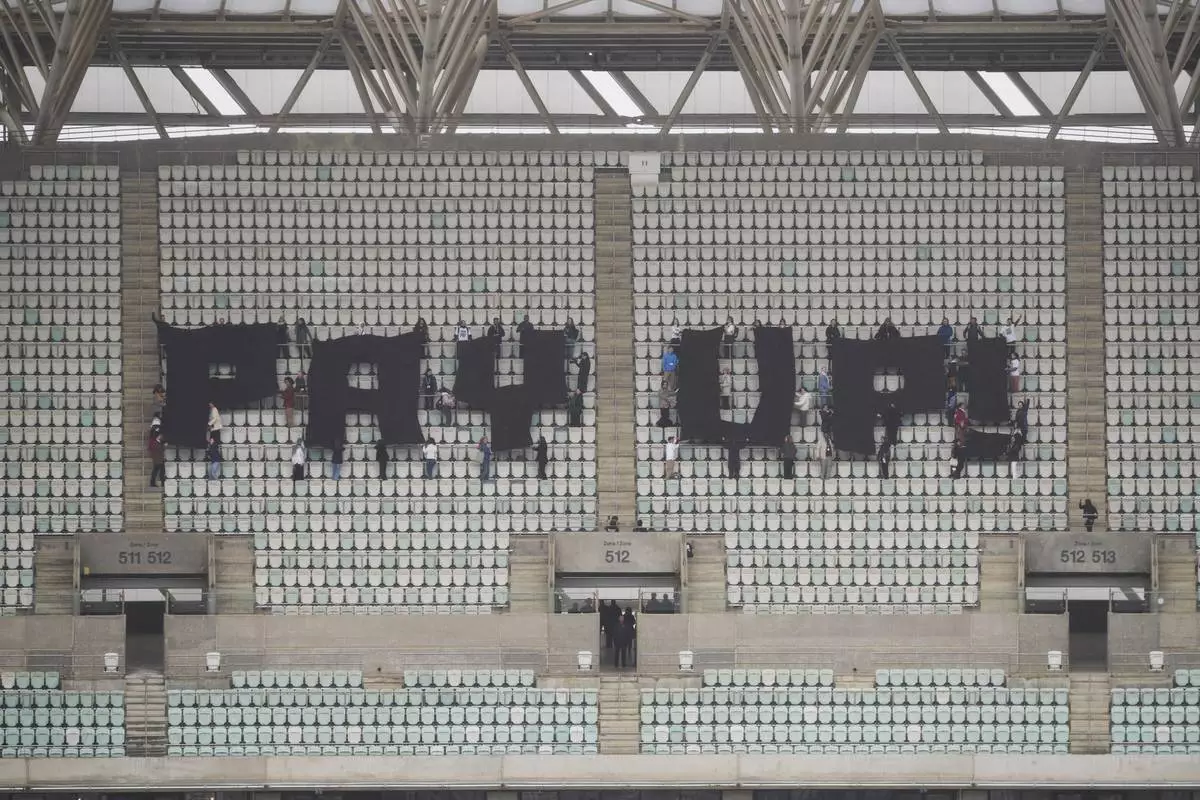

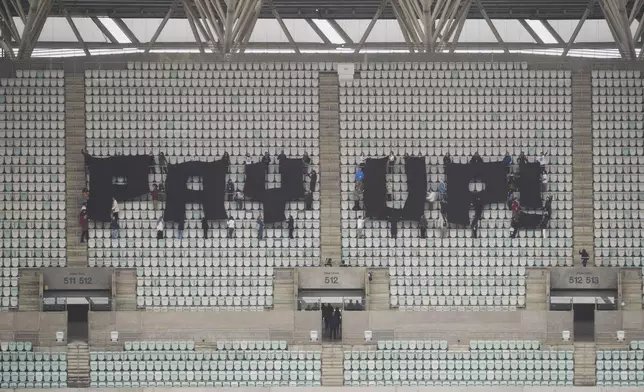

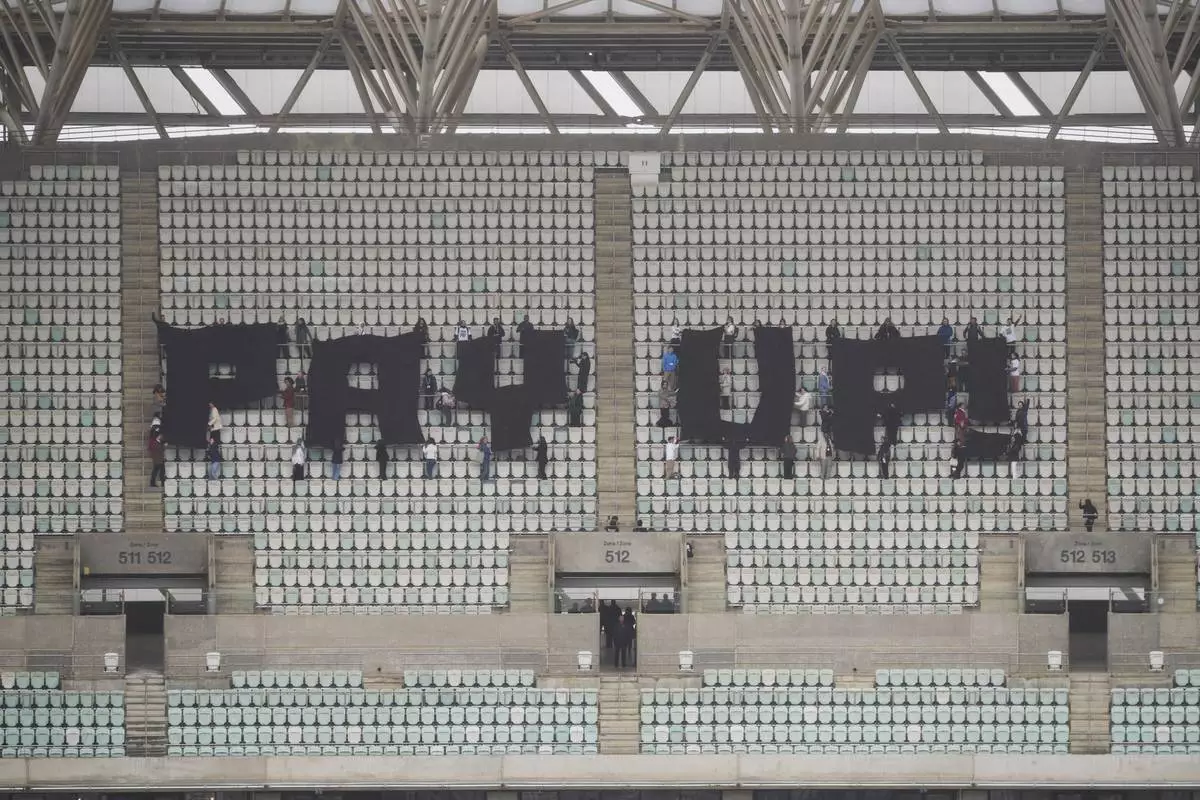

BAKU, Azerbaijan (AP) — In the nosebleed seats of a nearly-empty Baku Olympic stadium coated with a layer of dust, activists used a giant banner to beam the words “Pay Up” to the world.

The protest took weeks of thought and planning, but most of the attendees at this year's U.N. climate talks didn't see or hear it — except for maybe some in the COP29 presidency offices right below. The majority of the people involved in deciding the financial future of climate action at the talks remained in the sprawling venue, under white tarps with no windows.

Click to Gallery

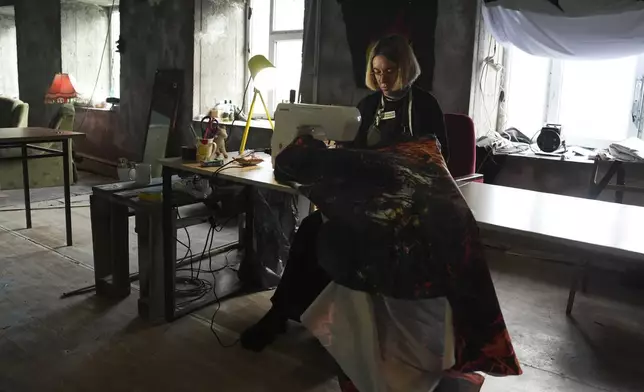

Anna Varszegi, of Budapest, Hungary, works on preparations for a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Dani Rupa, from Budapest, Hungary, paints a snake for a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

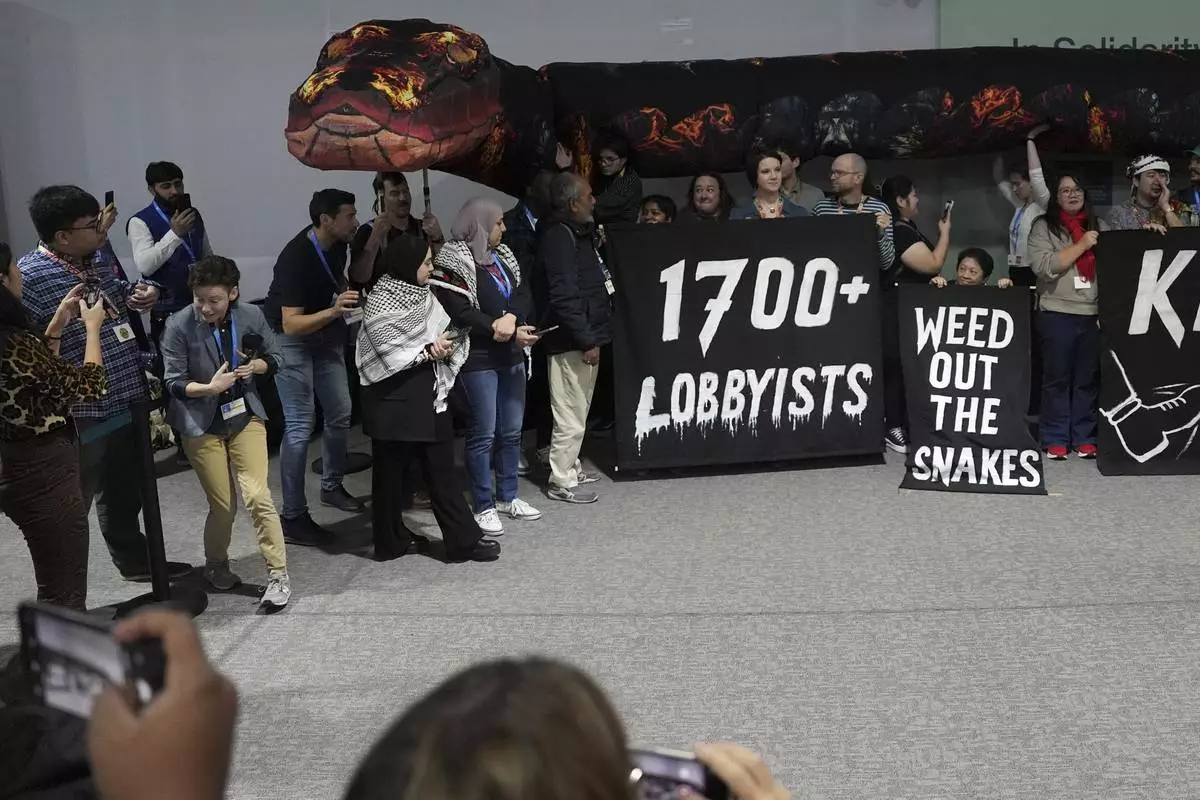

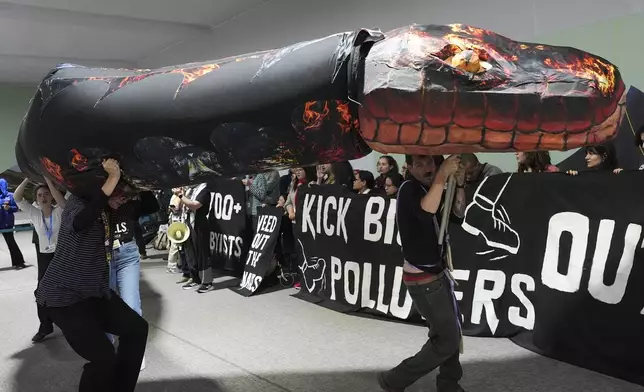

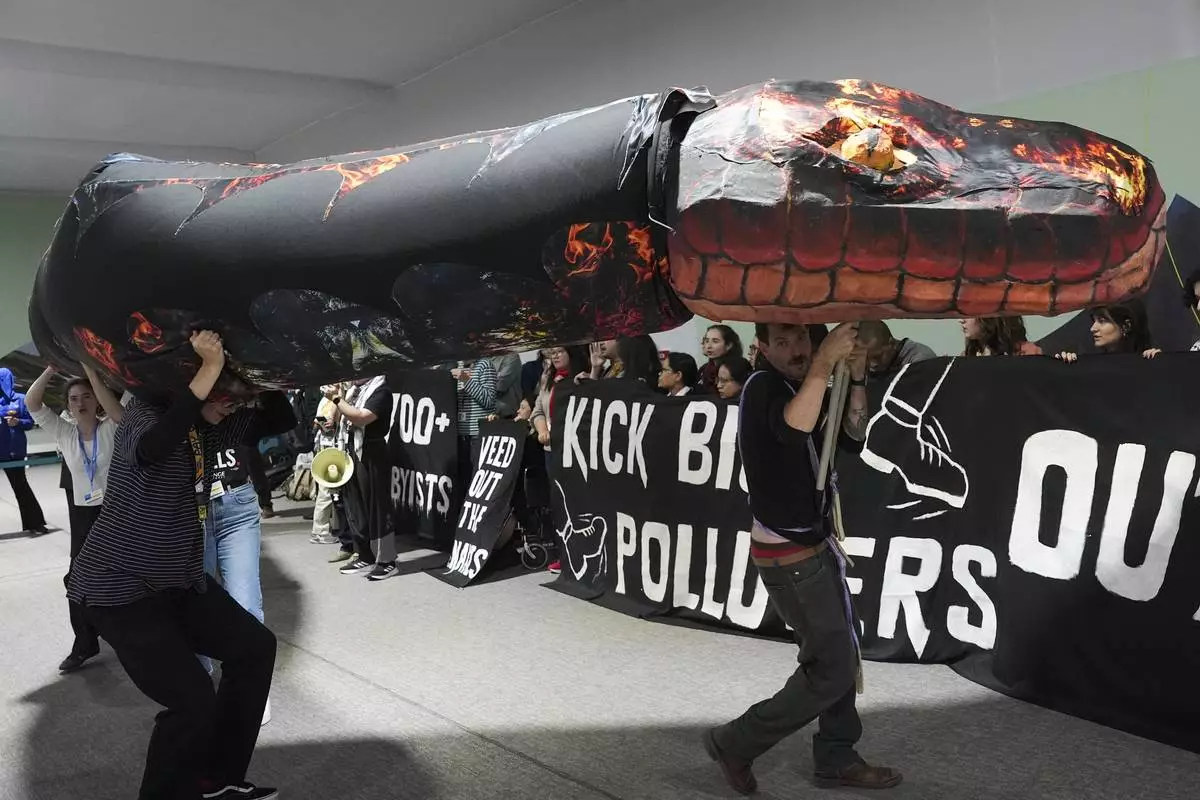

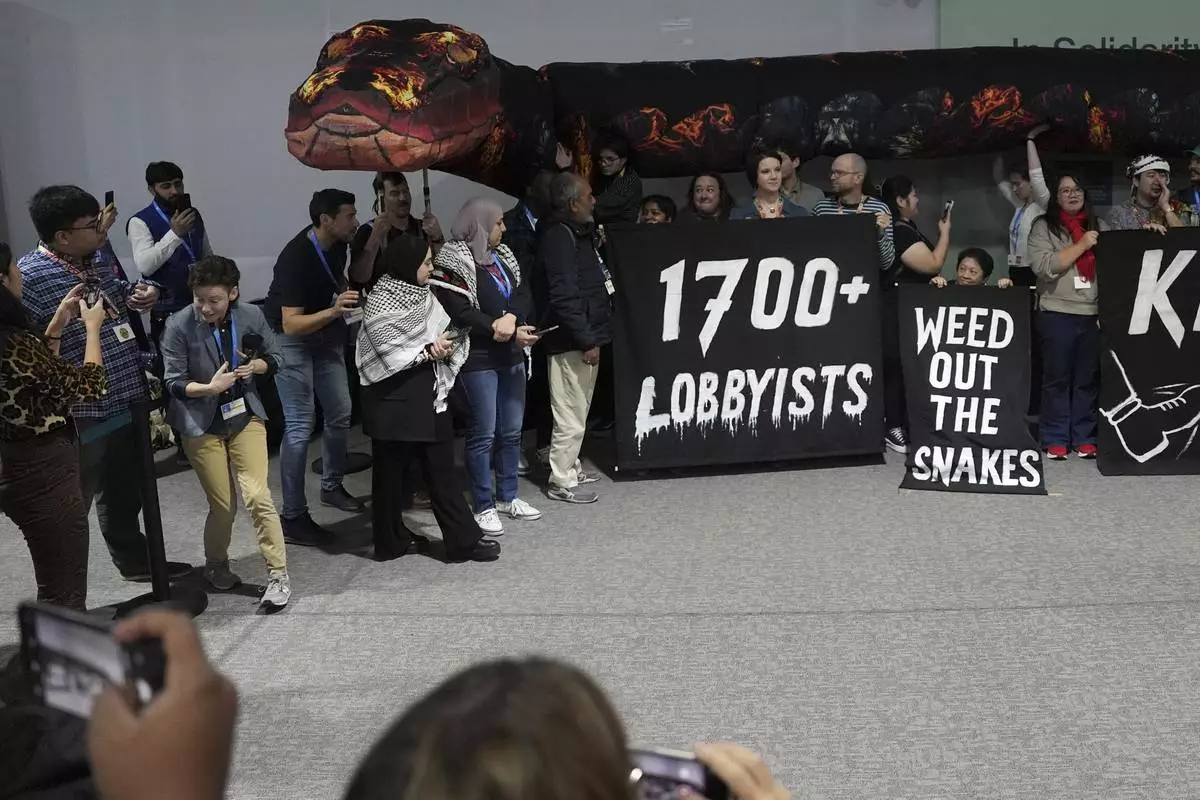

Kevin Buckland, right, and other activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels called weed out the snakes at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Activists with signs spell out "pay up" for climate finance in the Baku Olympic Stadium during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Activists with signs spell out "pay up" for climate finance in the Baku Olympic Stadium during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

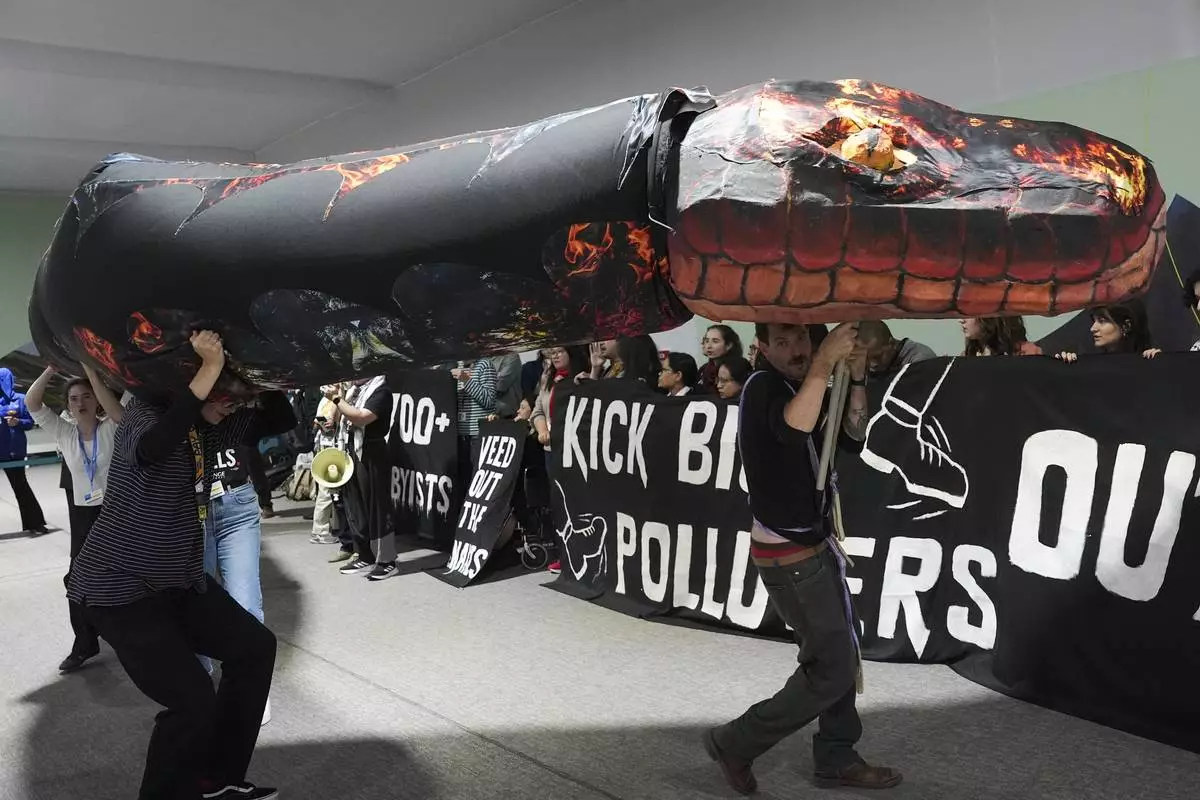

Kevin Buckland, front, and other activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels called weed out the snakes at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Shaq Koyok, of Malaysia, paints a sign ahead of a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Anna Varszegi, of Budapest, Hungary, sketches out patterns during preparations for a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Dani Rupa, from Budapest, Hungary, paints a snake for a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels called weed out the snakes at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

It’s “really hard to make our demands heard,” said Bianca Castro, a climate activist from Portugal. She’s been to several COPs in the past and remembers years when there were thousands of protestors in the streets, and a multitude of strikes and actions throughout the event. But at the stadium's seats, they were told exactly where and when they could stand and chants were restricted. A United Nations climate change spokesperson said that the action was in a part of the venue that isn’t open to participants, and involved extensive dialogue among the participants, facility managers and health and safety officers.

Still, Castro said the difficulty of making an impact meant many are "losing hope in the in the process."

People involved in protests say they have felt a trend in recent years of stricter rules from the United Nations organizers with COPs being held in countries whose governments limit demonstrations and the participation of civil society. And some community spaces for prepping and organizing have had to resort to going underground because of security concerns. But the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change — who run the COPs — say the code of conduct that governs the conferences has not changed, nor has the way it's applied, and COP29 organizers say there's space across the venue for participants to “make their voices heard in line with the UNFCCC code of conduct and Azerbaijan law safely and without interference.”

Despite the challenges and what some see as a depressing mood, activists say it remains a critical time to speak up about the historical and present-day injustices that are in desperate need of money and attention.

It's especially true this year at a COP where the theme is finance, because voices from the Global South play a pivotal role in bringing ambitious demands to the negotiating table, said Rachitaa Gupta, who coordinates a global network of organizations advocating for climate justice. But she said that there have been more and more defamation rules each year that prohibit protestors from calling out specific countries or names.

“We do feel that the restrictions have reached a stage where it’s a constant battle on what we can say,” Gupta said. Activists can’t name specific countries, people or businesses in line with the UNFCCC’s code of conduct.

Meanwhile, across town in a downtown Baku building, activists paint, snip fabric and sculpt with cardboard and papier-mache in a quest for visually compelling symbols of climate action. The art space was once a place of community, where people came to pour their feelings into a creative outlet, said Amalen Sathananthar, coordinator at a collective called the Artivist Network. But now his team keeps the art space private and doesn't reveal its location because of security concerns.

Restrictions, though, can breed creativity among the artists designing the banners, flags and props that demonstrators use during protests. In the absence of naming specific people or countries, or carrying country flags, they instead have to come up with other imagery to get their messages across.

One of this year’s pieces was a larger-than-life snake for an action with the slogan “Weed Out the Snakes,” calling attention for the removal of big polluters and fossil fuel lobbyists at climate talks, something that's been “outrageous,” said Jax Bongon, whose organization is part of the Kick Big Polluters Out coalition. “Would you invite an arsonist to put out the fire?”

It's an issue that's "particularly hard for me as someone from the Philippines,” Bongon added, but called it "really uplifting" to watch the action come together despite challenges.

Demonstrators hoisted the fire-colored serpent with on their shoulders and heads. Together, their hisses filled the tent, bringing the snake to life.

“I think that the only reason people dare to do this is because, one, they're struggling on how to be heard,” said Dani Rupa, one of the artists working in Baku with The Artivist Network. “But, two, that there is like creative support for them to be able to do this.”

The Artivist Network have been doing this for a long time, attending COPs unofficially since the early 2000s and officially since they formalized in 2018. Sathananthar's seen the multitude of ways protestors have had to argue with host countries and the UNFCCC governing body to get space for activism. But this year, especially, he said it's a struggle — “negotiations within negotiations” that have had Sathananthar staying up late into the night in talks and on occasion have left him “fuming.”

A spokesperson for UNFCCC said they've “been a recognized global leader in ensuring safe civic spaces at COPs for many years" which normally doesn't happen at other intergovernmental events.

Still, activists feel that only being able to protest within certain areas throughout the venue — when previous years have seen mass street marches in host cities — can be frustrating.

“Every action you now have to fight for desperately," Sathananthar said. “We fought to get these spaces and we will fight to keep them."

Follow Melina Walling on X at @MelinaWalling. Follow Joshua A. Bickel on X and Instagram.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Anna Varszegi, of Budapest, Hungary, works on preparations for a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Dani Rupa, from Budapest, Hungary, paints a snake for a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Kevin Buckland, right, and other activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels called weed out the snakes at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Activists with signs spell out "pay up" for climate finance in the Baku Olympic Stadium during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Activists with signs spell out "pay up" for climate finance in the Baku Olympic Stadium during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Kevin Buckland, front, and other activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels called weed out the snakes at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Shaq Koyok, of Malaysia, paints a sign ahead of a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Anna Varszegi, of Budapest, Hungary, sketches out patterns during preparations for a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Dani Rupa, from Budapest, Hungary, paints a snake for a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels called weed out the snakes at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

SEOUL, South Korea (AP) — South Korean opposition leader Lee Jae-myung was convicted of violating election law and sentenced to a suspended prison term Friday by a court that ruled he made false statements while denying corruption allegations during a presidential campaign.

If it stands, the ruling could significantly shake up the country’s politics by potentially unseating Lee as a lawmaker and denying him a shot at running for president in the next election. But Lee, who faces three other trials over corruption and other criminal charges, is expected to challenge any guilty verdict and it remains unclear whether the Supreme Court would decide on any of the cases before the presidential vote in March 2027.

Lee told reporters that he plans to appeal Friday’s verdict at the Seoul Central District Court, which gave him a sentence of one year in prison, suspended for two years. Under South Korean law, Lee would lose his legislative seat and be barred from running in elections for five years if he receives either a penalty exceeding a 1 million won ($715) fine for election law violations or any prison sentence for other crimes.

“There are still two more courts left in the real world, and the courts of public opinion and history are eternal,” he said, apparently referring to plans to take the case to the Supreme Court. “This is a conclusion that’s impossible to accept.”

Lee, a firebrand liberal who narrowly lost the 2022 election to conservative President Yoon Suk Yeol, had steadfastly denied wrongdoing. Choo Kyung-ho, the floor leader of Yoon’s People Power Party, said the verdict showed that “justice was alive” and called for the judiciary to conclude the case swiftly.

The ruling drew intense media coverage and seemingly thousands of protesters. Surrounded by police lines, Lee’s supporters and critics occupied separate streets near the court, shouting opposing slogans and holding signs that said “Lee Jae-myung is innocent” and “Arrest Lee Jae-myung.” There were no immediate reports of major clashes.

Prosecutors indicted Lee in 2022 over charges that he made false claims related to two controversial development projects in the city of Seongnam, where he was mayor from 2010 to 2018, while campaigning as the presidential candidate for the Democratic Party.

One of the comments cited by prosecutors is related to suspicions that Seongnam city in 2015 changed the land-use designation to allow a housing project on a site previously preserved as green space due to lobbying by private developers.

Lee said during a parliamentary hearing in October 2021 that the city was instead “coerced” by the national government to make the change to the site in the district of Baekhyeon-dong. Prosecutors say there’s no evidence to back Lee’s claim, which has been denied by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport.

Prosecutors also cited a TV interview Lee gave in December 2021, when he said he didn’t know a senior official at Seongnam city’s urban development arm during his time as mayor. Lee spoke a day after the official was found dead amid an investigation into a property development project in the district of Daejang-dong, which reaped huge profits for a small asset management firm and its affiliates and raised suspicions about possible corrupt links between them, city officials and politicians.

Prosecutors argued that Lee was lying to the public to distance himself from the controversies and improve his chances of winning the election. They had sought a two-year prison sentence for him.

The court found Lee guilty over the comments related to the Baekhyeon-dong project, saying it was clear that the city’s decision to change the site’s land-use designation wasn’t based on demands by the land ministry. It acquitted Lee on most of the charges related to his Daejang-dong comments, citing a lack of evidence.

“When false information is distributed to voters during an election process, that could prevent voters from making proper choices and risks distorting the will of the people and damaging the function of the electoral system,” the court said in a statement. “Such actions cannot be taken lightly.”

The same court on Nov. 25 will rule on another case against Lee. He is accused of suborning perjury by allegedly pressuring a Seongnam city employee to give false testimony in a different court case in 2019. The testimony was meant to downplay his 2003 conviction that, when as a lawyer, he had helped a TV journalist impersonate a prosecutor to secure an interview with then-Seongnam Mayor Kim Byung-ryang over suspected corruption in 2002.

While running for Gyeonggi Province governor in 2018, Lee claimed he had been wrongly accused over the incident, prompting prosecutors to indict him on a charge of making false statements during an election campaign. Lee was acquitted in 2019, partially based on the testimony of the city employee, who had worked as Kim's secretary and said he contemplated dropping charges against the journalist to make Lee the main culprit of the incident.

Prosecutors indicted Lee on the perjury charges in October last year, presenting transcripts of telephone conversations that they said showed Lee persuading the employee to testify in court that he was framed.

A third and more significant trial at the Seoul Central District Court involves various criminal allegations stemming from Lee’s days as Seongnam mayor, including that he provided unlawful favors to private investors involved in the two development projects seen as dubious.

Lee is also facing a trial at the Suwon District Court over allegations that he pressured a local businessman into sending millions of dollars in illegal payments to North Korea as he tried to set up a visit to that country that never materialized.

While denying wrongdoing, Lee has accused the government of Yoon, a prosecutor-turned-president, of pursuing a political vendetta.

Yoon, who has seen his approval ratings drop to the 20s in recent weeks, is grappling with his own political scandal. It centers around allegations that Yoon and first lady Kim Keon Hee exerted inappropriate influence on the People Power Party to pick a certain candidate to run for a parliamentary by-election in 2022 at the request of election broker Myung Tae-kyun, who was arrested this week.

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung, center, arrives at the Seoul Central District Court in Seoul, South Korea, Friday, Nov. 15 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung, center, arrives at the Seoul Central District Court in Seoul, South Korea, Friday, Nov. 15 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung, center, arrives at the Seoul Central District Court in Seoul, South Korea, Friday, Nov. 15 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)

South Korea's main opposition Democratic Party leader Lee Jae-myung, center, arrives at the Seoul Central District Court in Seoul, South Korea, Friday, Nov. 15 2024. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon)