BAKU, Azerbaijan (AP) — Nisreen Elsaim has been a climate activist for a dozen years, much of it focusing on the intersection of war and climate change. In April 2023, it became personal, when she awoke in her native Sudan to the explosions and gunfire of an erupting civil war.

Elsaim, her husband and their infant son eventually fled the country, among the millions displaced by a war that decimated crops and livelihoods. Those who went to refugee camps found themselves displaced again when heavy rains and flooding destroyed shelters and severely hindered aid delivery in a country the United Nations ranks as one of the world’s most vulnerable to climate change.

Click to Gallery

Simon Stiell, United Nations climate chief, left, talks with Achim Steiner, United Nations development programme administrator, at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Wednesday, Nov. 13, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

FILE - Palestinians evacuate a body from a site hit by an Israeli bombardment on Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip, Saturday, July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi, File)

Activists demonstrate for climate justice and a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 11, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Simon Stiell, United Nations climate chief, left, talks with Achim Steiner, United Nations development programme administrator, at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Wednesday, Nov. 13, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Activists say they read names of victims of genocide during a demonstration at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Activist Mohammed Usrof participates in a demonstration for climate justice and a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 11, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool)

It’s a story Elsaim is telling at the United Nations climate talks in Baku, which she says must succeed for countries like hers to have any chance to successfully adapt to climate change.

“We don’t have the privilege of losing hope,” she said.

The chief goal of COP29, as this year’s talks are known, is working out how much money wealthier nations will pay to help developing countries like Sudan. It’s a task that all sides — world leaders, protesters and experts — say is made more difficult by wars like those enveloping Gaza and Ukraine.

The wars are a distraction from confronting the climate crisis, they say. They waste money that could be used in the climate fight. And they cast doubt on the world’s ability to cooperate.

“We meet at a moment where faith in our ability to stand together is broken,” Al Hussein bin Abdullah, the crown prince of Jordan, said in a speech in Baku’s opening days. “Saving our planet must start from the premise that all lives are worth saving. The solidarity we need depends on embracing that truth.”

Many world leaders used their opening remarks to describe how extreme weather had ravaged their countries, making issues such as poverty, energy security and access to water and food worse or more uncertain. And that risks more conflict, they said.

“Climate change is now emerging as a major global threat and influencing the escalating of geopolitical tensions. It primarily exacerbates the problems of poverty eradication, food and energy security as well as access to water and resources," Uzbekistan President Shavkat Mirziyoyev said.

In the Middle East, Israel’s war in Gaza has caused widespread destruction, including collapsing water and sanitation systems. It's also undone Gaza’s progress in a range of environmental areas, including solar power, water desalination facilities and wetlands restoration, according to the United Nations Environment Programme. The destruction of solar panels threatens soil and water with leaks of lead and other heavy metals, the UN said.

And Russia's war in Ukraine has sent the equivalent of 150 million tons of heat-trapping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere that wouldn't have happened without the war, according to a 2023 report from the Initiative on Greenhouse Gas Accounting of War, a group of researchers whose funding comes in part from the European Climate Foundation. That's more than the annual greenhouse gas emissions from a country like Belgium.

Achim Steiner, chief administrator for the United Nations Development Programme, said billions of dollars that could be used for poverty eradication, climate finance, education and other good causes are instead going toward war.

“We are a more divided world and a divided world struggles to sit around the table and overcome differences in order to focus on shared interests,” Steiner said.

Dozens of protesters in Baku specifically targeted Western support for Israel. One of them, Lise Masson of Friends of the Earth International, said countries like the United States and Britain, as well as the European Union, could spend more on climate finance instead.

“It’s the same systems of oppression and discrimination that are putting people on the front lines of climate change and putting people on the front lines of conflict in Palestine," she said.

Catherine Abreu, director of the International Climate Politics Hub, a network of organizations and people working on climate action, agreed that wars add to “cascading crises” and can stretch a government’s ability to respond to other problems. And she said it would be “incredibly powerful” if those wars ended and military spending was immediately shifted to climate action.

“When, you know, the ability of developing countries in particular to adapt to and respond to these crises was being better supported by the wealthy global north then we might see an acceleration of climate action,” she said.

But she said she sees broader challenges — the COVID hangover, heavy debt loads and economic slowdowns — as primarily responsible for slow progress in climate talks.

Greg Puley, head of the United Nations' Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, acknowledged concern that global conflict could prevent leaders at COP29 from reaching “the most ambitious possible deal.” But he and others are determined to avoid that.

“We cannot afford for business as usual to continue. We cannot afford for the difficult geopolitical environment to prevent major reductions in emissions, major new investments in adaptation and resilience," Puley said. “We’re not going to be able to respond to the climate-related disasters of the future unless we take bold steps now.”

Pineda reported from Los Angeles.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

FILE - Palestinians evacuate a body from a site hit by an Israeli bombardment on Khan Younis, southern Gaza Strip, Saturday, July 13, 2024. (AP Photo/Jehad Alshrafi, File)

Activists demonstrate for climate justice and a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 11, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Simon Stiell, United Nations climate chief, left, talks with Achim Steiner, United Nations development programme administrator, at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Wednesday, Nov. 13, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Activists say they read names of victims of genocide during a demonstration at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Activist Mohammed Usrof participates in a demonstration for climate justice and a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 11, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool)

BAKU, Azerbaijan (AP) — Cities in Asia and the United States emit the most heat-trapping gas that feeds climate change, with Shanghai the most polluting, according to new data that combines observations and artificial intelligence.

Nations at U.N. climate talks in Baku, Azerbaijan are trying to set new targets to cut such emissions and figure out how much rich nations will pay to help the world with that task. The data comes as climate officials and activists alike are growing increasingly frustrated with what they see as the talks' — and the world's — inability to clamp down on planet-warming fossil fuels and the countries and companies that promote them.

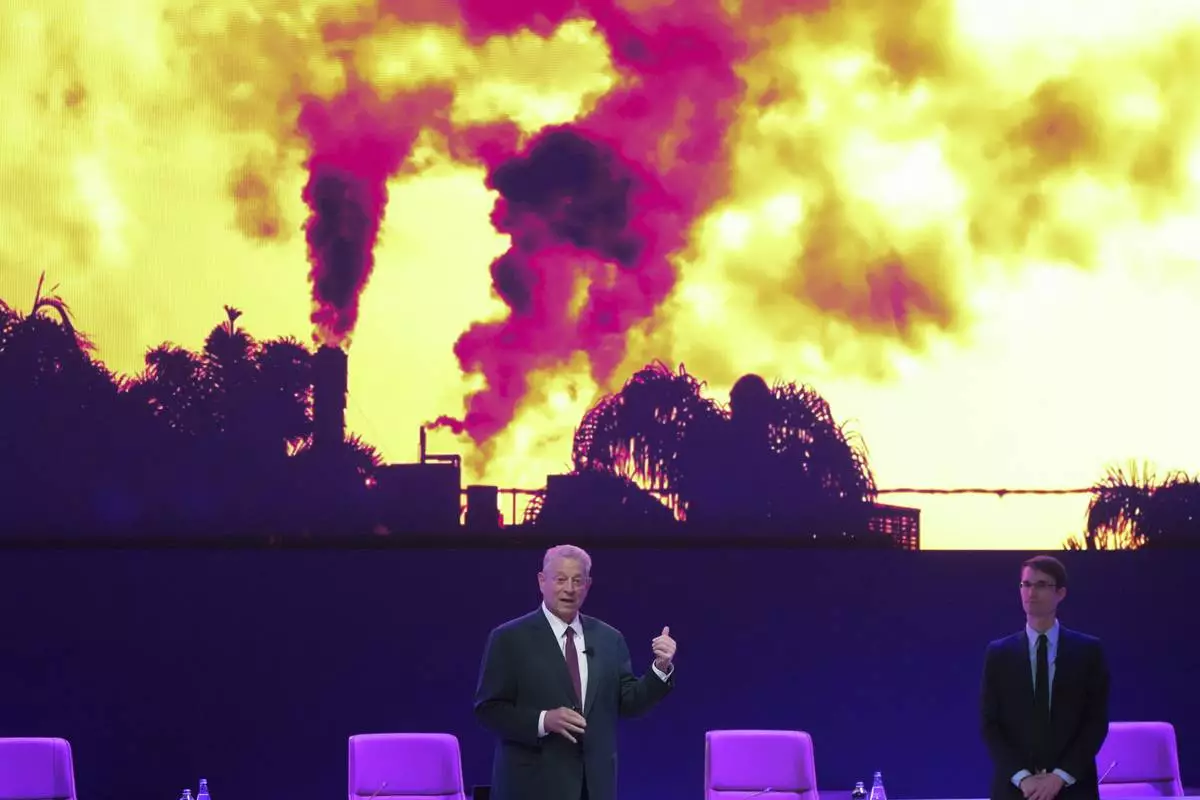

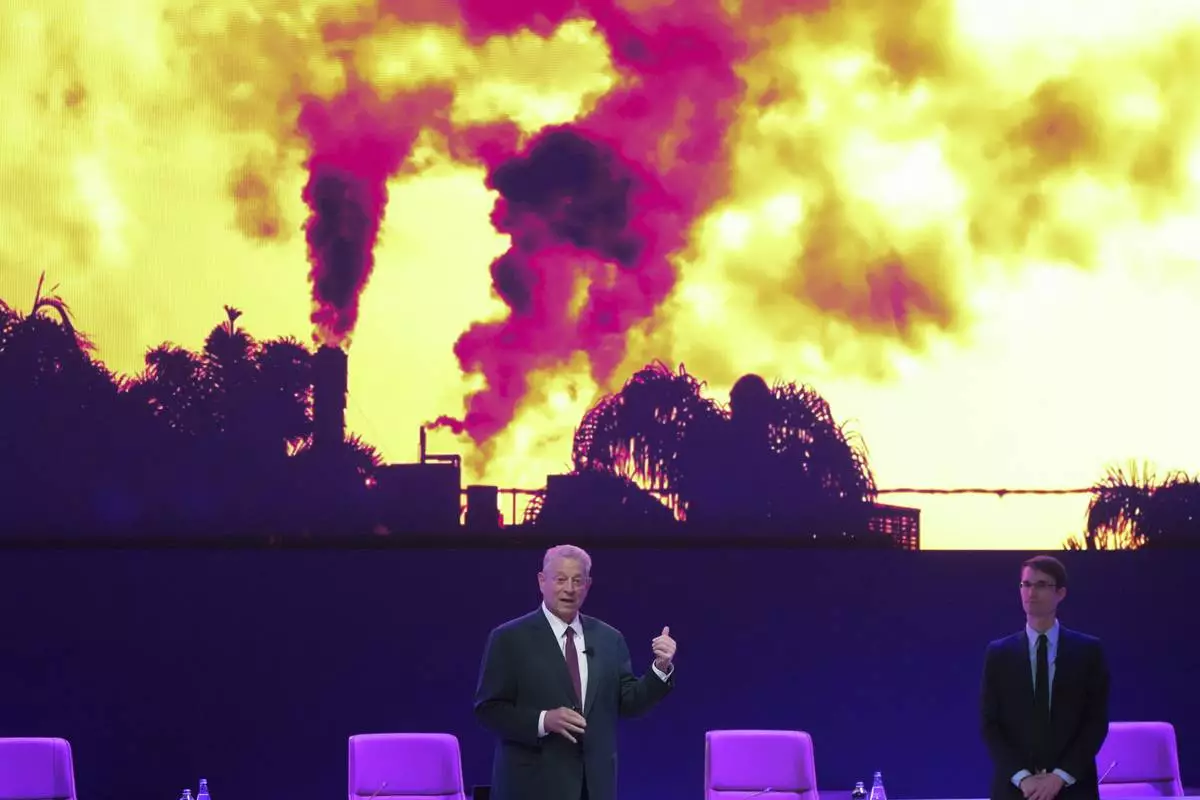

Seven states or provinces spew more than 1 billion metric tons of greenhouse gases, all of them in China, except Texas, which ranks sixth, according to new data from an organization co-founded by former U.S. Vice President Al Gore and released Friday at COP29.

Using satellite and ground observations, supplemented by artificial intelligence to fill in gaps, Climate Trace sought to quantify heat-trapping carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide, as well as other traditional air pollutants worldwide, including for the first time in more than 9,000 urban areas.

Earth's total carbon dioxide and methane pollution grew 0.7% to 61.2 billion metric tons with the short-lived but extra potent methane rising 0.2%. The figures are higher than other datasets “because we have such comprehensive coverage and we have observed more emissions in more sectors than are typically available,” said Gavin McCormick, Climate Trace's co-founder.

Shanghai's 256 million metric tons of greenhouse gases led all cities and exceeded those from the nations of Colombia or Norway. Tokyo's 250 million metric tons would rank in the top 40 of nations if it were a country, while New York City's 160 million metric tons and Houston's 150 million metric tons would be in the top 50 of countrywide emissions. Seoul, South Korea, ranks fifth among cities at 142 million metric tons.

“One of the sites in the Permian Basin in Texas is by far the No. 1 worst polluting site in the entire world,” Gore said. “And maybe I shouldn’t have been surprised by that, but I think of how dirty some of these sites are in Russia and China and so forth. But Permian Basin is putting them all in the shade.”

China, India, Iran, Indonesia and Russia had the biggest increases in emissions from 2022 to 2023, while Venezuela, Japan, Germany, the United Kingdom and the United States had the biggest decreases in pollution.

The dataset — maintained by scientists and analysts from various groups — also looked at traditional pollutants such as carbon monoxide, volatile organic compounds, ammonia, sulfur dioxide and other chemicals associated with dirty air. Burning fossil fuels releases both types of pollution, Gore said.

This “represents the single biggest health threat facing humanity,” Gore said.

Gore criticized the hosting of climate talks, called COPs, by Azerbaijan, an oil nation and site of the world's first oil wells, and by the United Arab Emirates last year.

“It’s unfortunate that the fossil fuel industry and the petrostates have seized control of the COP process to an unhealthy degree,” Gore said. “Next year in Brazil, we’ll see a change in that pattern. But, you know, it’s not good for the world community to give the No. 1 polluting industry in the world that much control over the whole process.”

Brazil President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has called for more to be done on climate change and has sought to slow deforestation since returning for a third term as president. But Brazil last year produced more oil than both Azerbaijan and the United Arab Emirates, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

On Friday, former U.N. secretary-general Ban Ki-moon, former U.N. climate chief Christina Figueres and leading climate scientists released a letter calling for “an urgent overhaul” on climate talks.

The letter said the “global climate process has been captured and is no longer fit for purpose” in response to Azerbaijan's president Ilham Aliyev saying that oil and gas are a “gift of the gods.”

U.N. Environment Programme Executive Director Inger Andresen said she understands much of the frustration in the letter calling for massive reform of the negotiation process, but said their push to slash emissions fits nicely with U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres’ constant prodding.

One key benefit of the U.N. climate talks process is it is the only place where victim small island nations have an equal seat at the table, Andersen told The Associated Press. But the process has its limits because “the rules of the game are set by member states,” she said.

An analysis from the Kick Big Polluters Out coalition said Friday that the official attendance list of the talks featured at least 1,770 fossil fuel lobbyists.

At a press conference with small island nations chair Cedric Schuster said the negotiating bloc feels the need to remind everyone else why the talks matter.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Eric Njuguna, of Kenya, participates in a demonstration against fossil fuels at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Eric Njuguna, of Kenya, participates in a demonstration against fossil fuels called weed out the snakes at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Former Vice President Al Gore speaks during a session on Climate Trace, a database that monitors emissions, at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Former Vice President Al Gore speaks during a session on Climate Trace, a database that monitors emissions, at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)