BAKU, Azerbaijan (AP) — Extreme heat ruined the pineapples on Esther Penunia's small farm in the Philippines this year, more disappointment than catastrophe since Penunia doesn't depend on the farm for a living. But Penunia worries about the millions of small farmers in her part of the world who do depend on rice paddies, coconut groves and vegetable patches that are all threatened by climate change.

That’s why she’s hoping that countries at this year’s United Nations climate summit will dedicate some of the money for fighting climate change to agriculture — and the family farmers who feed most of the people in many parts of the world.

“You don’t help small farmers, where will you get your food?" wondered Penunia, secretary general of the Asian Farmers Association. "Who will farm for you? Who will catch the fish, who will get the honey, who will plant your vegetables?”

Many countries, especially in the Global South, need money to help pay for the months of recovery when typhoons wreck fields, to insure farmers against more extreme droughts and to prepare for a hotter world with better seeds, better fertilizers and better water infrastructure. But there's a massive gap between the $1 trillion in climate finance that poorer countries need, according to experts from the World Resources Institute, and what richer countries are prepared to pay.

Whatever deal is reached, it's certain that the money will have to be stretched. And there's debate about exactly how much money should go toward agriculture and how much toward cutting fossil fuel emissions.

Small farmers get less than 1% of climate finance, according to a report last year from the Climate Policy Initiative. At the same time, food systems — all the processes involved in making, shipping and disposing of food — account for about a third of planet-warming greenhouse gas emissions.

Farmers' efforts to adapt to a warming climate get harder the hotter it gets, Ismahane Elouafi, executive managing director of CGIAR, a global partnership for agricultural research, said in a statement. At a COP29 panel on climate-smart solutions for smallholder farmers, she added: “If we want to solve the issue, how could we not invest in a sector that is having a third of the problem?”

Praveena Sridhar, chief science and technical officer of Save Soil, a movement aimed at raising awareness about soil health, offered a simpler reason for why countries should help fund agriculture's adaptation to climate change. As hard as it is to agree on cutting fossil fuel use, it should be easier to support farming solutions proven to work.

“We have not figured out the puzzle yet,” she said. “Why not look at the puzzle pieces we have figured out and start moving?”

Yet others worry that doing so would distract from tackling the biggest problem — fossil fuels.

Zeke Hausfather, a research scientist with the nonprofit Berkeley Earth, said in an email that there is “real potential” in land management changes to reduce carbon dioxide emissions. But the most that could cut emissions globally is around a billion tons a year, he said — just a tiny fraction of the 40 billion tons of carbon dioxide the world emits every year.

Hausfather also noted that carbon stored in the ground by more climate-conscious agricultural practices isn't guaranteed to stay there permanently, he said, referencing a paper he published this month.

That hasn't stopped some countries, companies and private investors from putting big money toward agricultural technology, including the $9 billion announced last year at COP28 for a joint U.S. and U.A.E.-backed project aimed at innovating in farming and food systems to adapt to climate change and cut emissions.

With the incoming Trump administration likely to reverse many U.S. climate initiatives, Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack said he hopes business, academic and farming interests keep climate-related agriculture projects going. “It’s always important to remember that we have three levels of government in the U.S. And there’s going to be a lot of activity in cities and states that’s going to complement what was being done in these initiatives that I think will continue,” Vilsack said.

The stakes are high for advocates like Penunia, who was disappointed that farmers weren't mentioned in language at the last U.N. climate talks.

“We hope that really we can be heard," she said.

Follow Melina Walling on X, formerly known as Twitter, @MelinaWalling.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

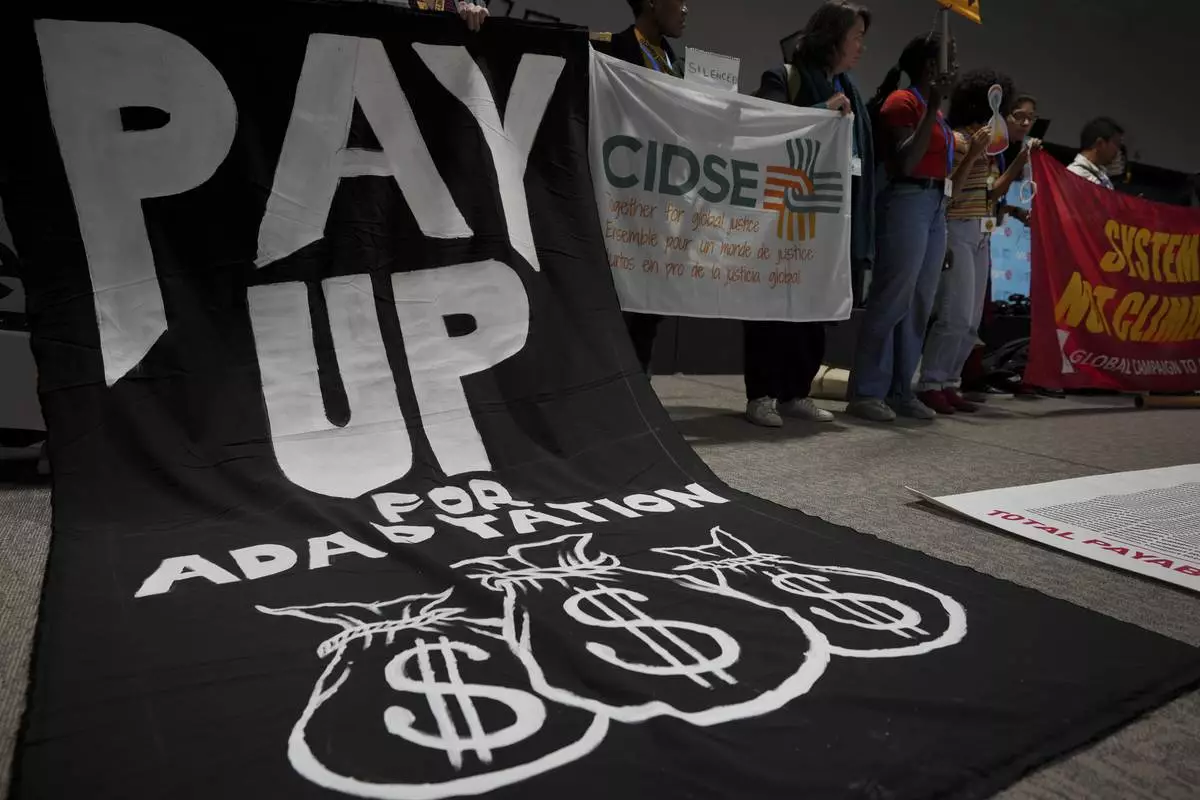

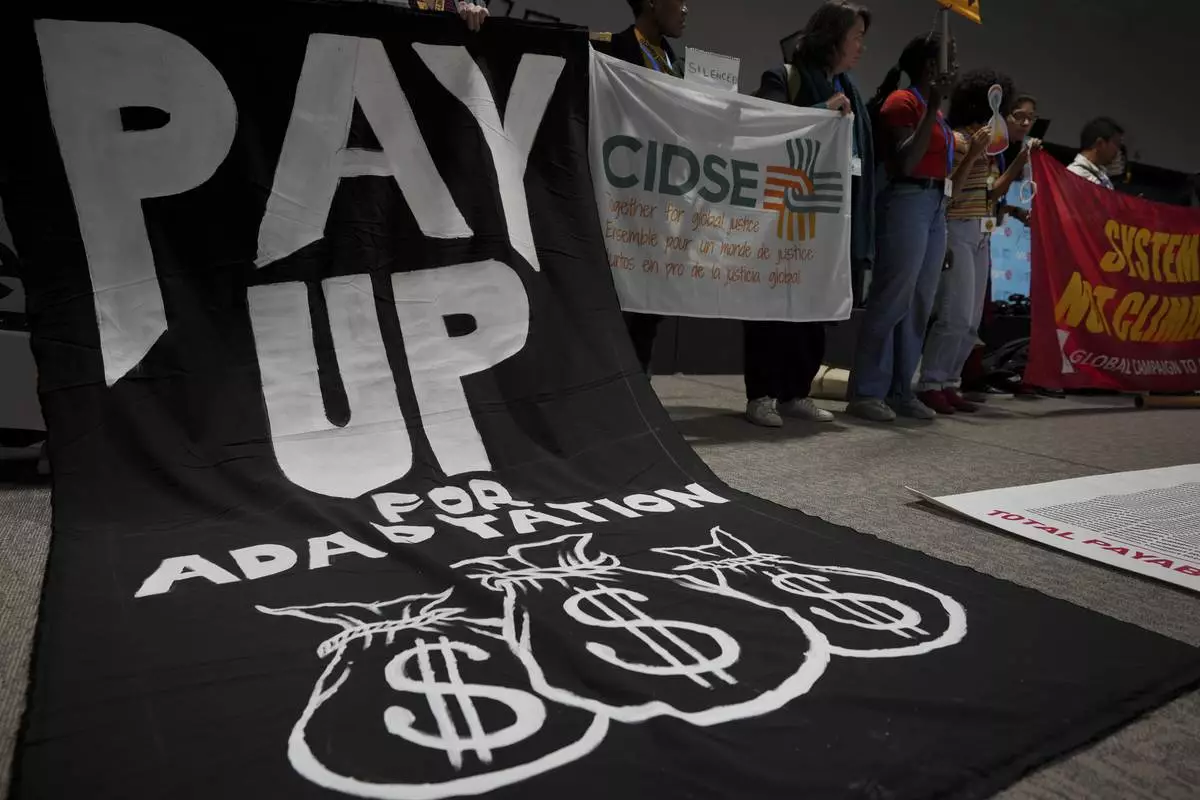

Activists participate in a demonstration for climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, center, speaks during a session at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

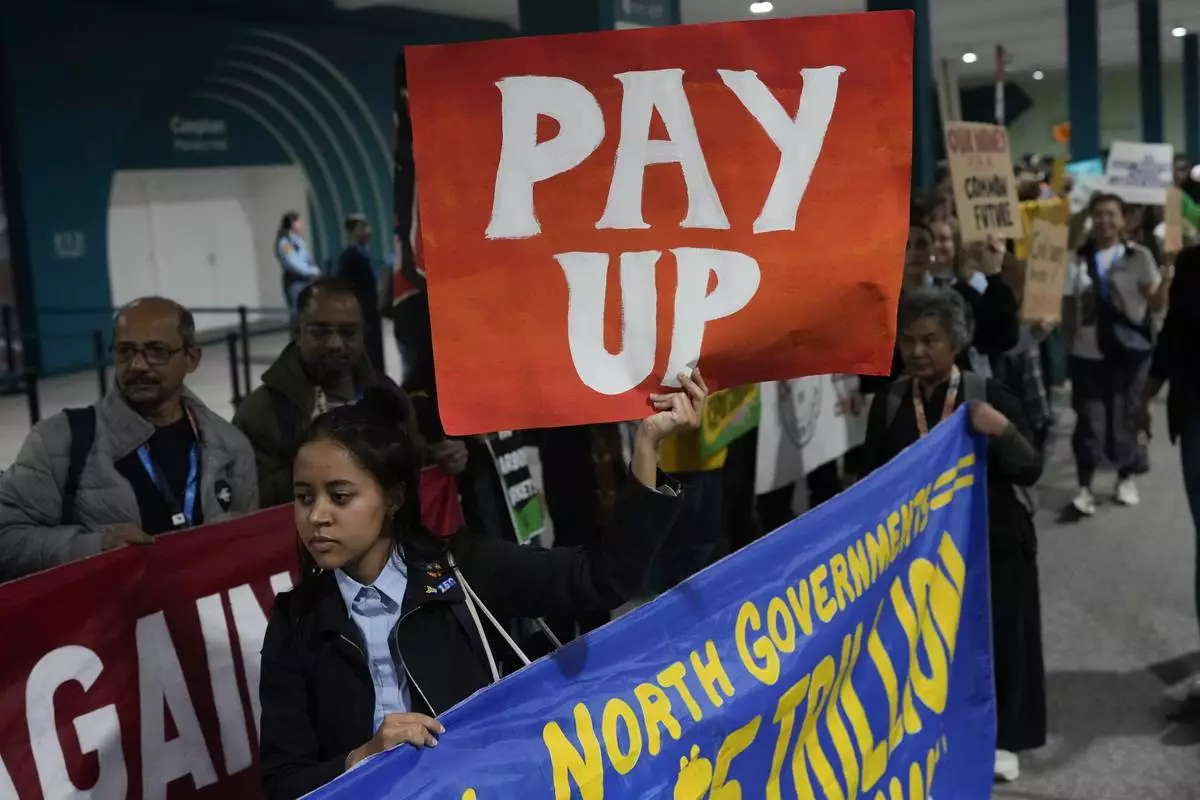

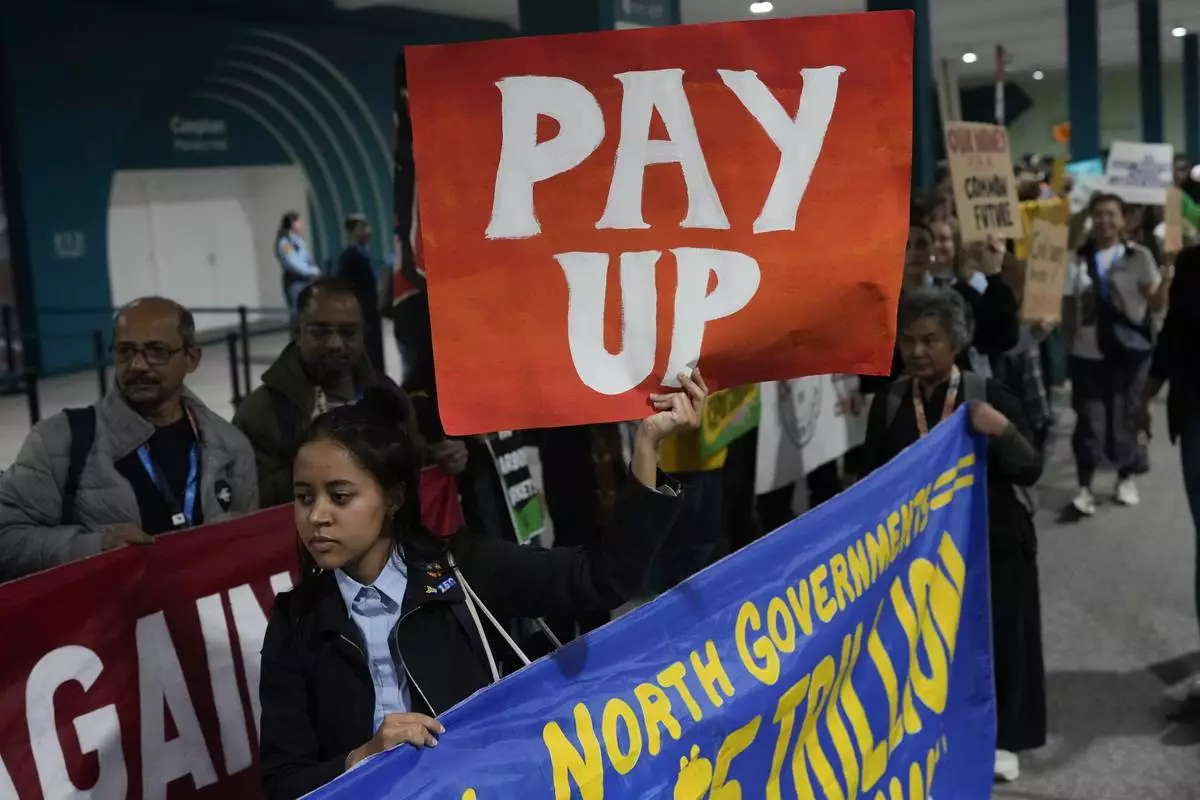

Activists participate in a demonstration for climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool)

WELLINGTON, New Zealand (AP) — As tens of thousands of marchers crowded the streets in New Zealand’s capital Wellington on Tuesday, the throng of people, flags aloft, had the air of a festival or a parade rather than a protest. They arrived to oppose a law that would reshape the county’s founding treaty between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown. But for many, it was about something more: a celebration of a resurging Indigenous language and identity that colonization had once almost destroyed.

“Just fighting for the rights that our tūpuna, our ancestors, fought for,” Shanell Bob said as she waited for the march to begin. “We’re fighting for our tamariki, for our mokopuna, so they can have what we haven’t been able to have,” she added, using the Māori words for children and grandchildren.

What was likely the country’s largest-ever protest in support of Māori rights — a subject that has preoccupied modern New Zealand for much of its young history — followed a long tradition of peaceful marches the length of the country that have marked turning points in the nation's story.

“We’re going for a walk!” One organizer proclaimed from the stage as crowds gathered at the opposite end of the city from the nation’s Parliament. Some had traveled the length of the country over the past nine days.

For many, the turnout reflected growing solidarity on Indigenous rights from non-Māori. At bus stops during the usual morning commute, people of all ages and races waited with Māori sovereignty flags. Some local schools said they would not register students as absent. The city’s mayor joined the protest.

The bill that marchers were opposing is unpopular and unlikely to become law. But opposition to it has exploded, which marchers said indicated rising knowledge of the Treaty of Waitangi’s promises to Māori among New Zealanders — and a small but vocal backlash from those who are angered by the attempts of courts and lawmakers to keep them.

Māori marching for their rights as outlined in the treaty is not new. But the crowds were larger than at treaty marches before and mood was changed, Indigenous people said.

“It’s different to when I was a child,” Bob said. “We’re stronger now, our tamariki are stronger now, they know who they are, they’re proud of who they are.”

As the marchers moved through the streets of Wellington with ringing Māori haka — rhythmic chants — and waiata, or songs, thousands more holding signs lined the pavement in support.

Some placards bore jokes or insults about the lawmakers responsible for the bill, which would change the meaning of the principles of the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi and prevent them from applying only to Māori — whose chiefs signed the document when New Zealand was colonized.

But others read “proud to be Māori” or acknowledged the bearer’s heritage as a non-Māori person endorsing the protest. Some denounced the widespread expropriation of Māori land during colonization, one of the main grievances arising from the treaty.

“The treaty is a document that lets us be here in Aotearoa so holding it up and respecting it is really important,” said Ben Ogilvie, who is of Pākehā or New Zealand European descent, using the Māori name for the country. “I hate what this government is doing to tear it down.”

Police said 42,000 people tried to crowd into Parliament’s grounds, with some spilling into the surrounding streets. People crammed themselves onto the children's slide on the lawn for a vantage point; others perched in trees. The tone was almost joyful; as people waited to leave the cramped area, some struck up Māori songs that most New Zealanders learn at school.

A sea of Māori sovereignty flags in red, black and white stretched down the lawn and into the streets. But marchers bore Samoan, Tongan, Indigenous Australian, U.S., Palestinian and Israeli flags, too. At Parliament, speeches from political leaders drew attention to the reason for the protest — a proposed law that would change the meaning of words in the country’s founding treaty, cement them in law and extend them to everyone.

Its author, libertarian lawmaker David Seymour — who is Māori — says the process of redress for decades of Crown breaches of its treaty with Māori has created special treatment for Indigenous people, which he opposes.

The bill’s detractors say it would spell constitutional upheaval, dilute Indigenous rights, and has provoked divisive rhetoric about Māori — who are still disadvantaged on almost every social and economic metric, despite attempts by the courts and lawmakers in recent decades to rectify inequities caused in large part by breaches of the treaty.

It is not expected to ever become law, but Seymour made a political deal that saw it shepherded through a first vote last Thursday. In a statement Tuesday, he said the public could now make submissions on the bill — which he hopes will reverse in popularity and experience a swell of support.

Seymour briefly walked out onto Parliament’s forecourt to observe the protest, although he was not among the lawmakers invited to speak. Some in the crowd booed him.

The protest was “a long time coming,” said Papa Heta, one of the marchers, who said Māori sought acknowledgement and respect.

“We hope that we can unite with our Pākehā friends, Europeans," he added. "Unfortunately there are those that make decisions that put us in a difficult place.”

Thousands of people gather outside New Zealand's parliament to protest a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlotte McLay-Graham)

Thousands of people gather outside New Zealand's parliament to protest a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

Thousands of people gather outside New Zealand's parliament to protest a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

ACT Party leader David Seymour, center, looks on as thousands of people gather outside New Zealand's parliament to protest a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

Protesters march carrying placards to New Zealand's parliament to demonstrate against a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington, New Zealand, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

Indigenous Māori people walk through the streets of Wellington, New Zealand to protest against a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

Indigenous Māori reacts outside New Zealand's parliament to protest against a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington, New Zealand, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

A protester reacts outside New Zealand's parliament during a demonstration against a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

Members of Te Āti Awa, join thousands of people gathered outside New Zealand's parliament to protest a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

A petition is delivered to Member of Parliament Rawiri Waititi, left, outside New Zealand's parliament during a protest against a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

Thousands of people gather outside New Zealand's parliament to protest a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

Indigenous Māori gather outside Parliament in Wellington, New Zealand, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

A man carries a child on his shoulders outside New Zealand's parliament during a protest against a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

Te Haukūnui Hokianga plays a conch shell ahead of a protest at New Zealand's parliament against a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington, New Zealand, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

Hana-Rāwhiti Maipi-Clarke speaks to the thousands of people gathered outside New Zealand's parliament to protest a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

New Zealand's opposition leader Chris Hipkins, left, does a hongi with Hare Arapere as people gathered outside New Zealand's parliament to protest a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

Thousands of people gather outside New Zealand's parliament to protest a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

Indigenous Māori people protest outside Parliament against a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington, New Zealand, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Mark Tantrum)

Thousands of people gather outside New Zealand's parliament to protest a proposed law that would redefine the country's founding agreement between Indigenous Māori and the British Crown, in Wellington Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Charlotte McLay-Graham)