BAKU, Azerbaijan (AP) — Just as a simple lever can move heavy objects, rich nations are hoping another kind of leverage — the financial sort — can help them come up with the money that poorer nations need to cope with climate change.

It involves a complex package of grants, loans and private investment, and it's becoming the major currency at annual United Nations climate talks known as COP29.

But poor nations worry they’ll get the short end of the lever: not much money and plenty of debt.

Half a world away in Brazil, leaders of the 20 most powerful economies issued a statement that among other things gave support to strong financial aid dealing with climate for poor nations and the use of leverage financial mechanisms. That was cheered by climate analysts and advocates. But at the same time, the G20 leaders noticeably avoided repeating the call for the world to transition away from fossil fuels, a key win at last year's climate talks.

Money is the key issue in Baku, where negotiators are working on a new amount for aid to help developing nations transition to clean energy, adapt to climate change and deal with weather disasters. It’ll replace the current goal of $100 billion annually — a goal set in 2009.

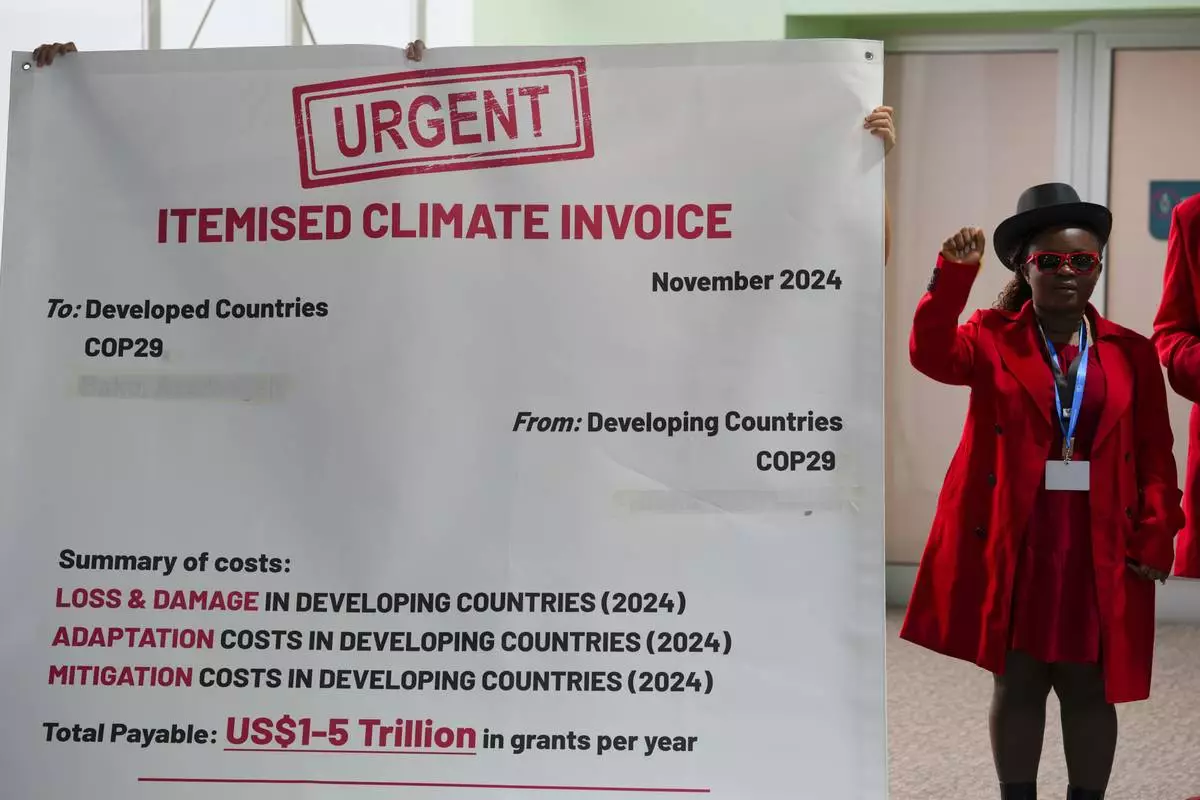

Experts put the need closer to $1 trillion, while developing nations have said they'll need $1.3 trillion in climate finance. But negotiators are talking about different types of money as well as amounts.

So far rich nations have not quite offered a number for the core of money they could provide. But the European Union is expected to finally do that and it will likely be in the $200 to $300 billion a year range, Linda Kalcher, executive director of the think tank Strategic Perspectives, said Tuesday. It might be even as much as four times the original $100 billion, said Luca Bergamaschi, co-founding director of the Italian ECCO think tank.

But there's a big difference between $200 billion and $1.3 trillion. That can be bridged with “the power of leverage," said Avinash Persaud, climate adviser for the Inter-American Development Bank.

When a country gives a multilateral development bank like his $1, it could be used with loans and private investment to get as much as $16 in spending for transitioning away from dirty energy, Persaud said. When it comes to spending to adapt to climate change, the bang for the buck, is a bit less, about $6 for every dollar, he said.

The World Bank president said all the multinational development banks could spend $125 billion on climate loans. Then those loans could be used as leverage for even more spending, several climate economics experts said.

“That's a big lever,” said Melanie Robinson, global climate economics and finance director at World Resources Institute.

But when it comes to compensating poor nations already damaged by climate change — such as Caribbean nations devastated by repeated hurricanes — leverage doesn't work because there's no investment and loans. That's where straight-out grants could help, Persaud said.

If climate finance comes mostly in the form of loans, except for the damage compensation, it means more debt for nations that are already drowning in it, said Michai Robertson, climate finance negotiator for the Alliance of Small Island States. And sometimes the leveraged or mobilized money doesn’t quite appear as promised, he said.

“All of these things are just nice ways of saying more debt,” Robertson said. “Are we here to address the climate crisis, which especially small developing states, least developed countries, have basically done nothing to contribute to it? The new goal cannot be a prescription of unsustainable debt.”

His organization argues that most of the $1.3 trillion it seeks should be in grants and very low-interest and long-term loans that are easier to pay back. Only about $400 billion should be in leveraged loans, Robertson said.

Another method for funding climate finance could be an international tax. That could be on shipping, aviation or billionaires, experts, such as Robertson, suggested.

That would be politically difficult, but “the reality is that the world cannot tax up to $1 trillion of the taxpayers to make this happen, which is why we have to think about development finance and climate finance,” said United Nations Environment Programme Director Inger Andersen suggested.

Leverage from loans “will be a critical part of the solution,” Andersen said. But so must grants and so must debt relief, she added.

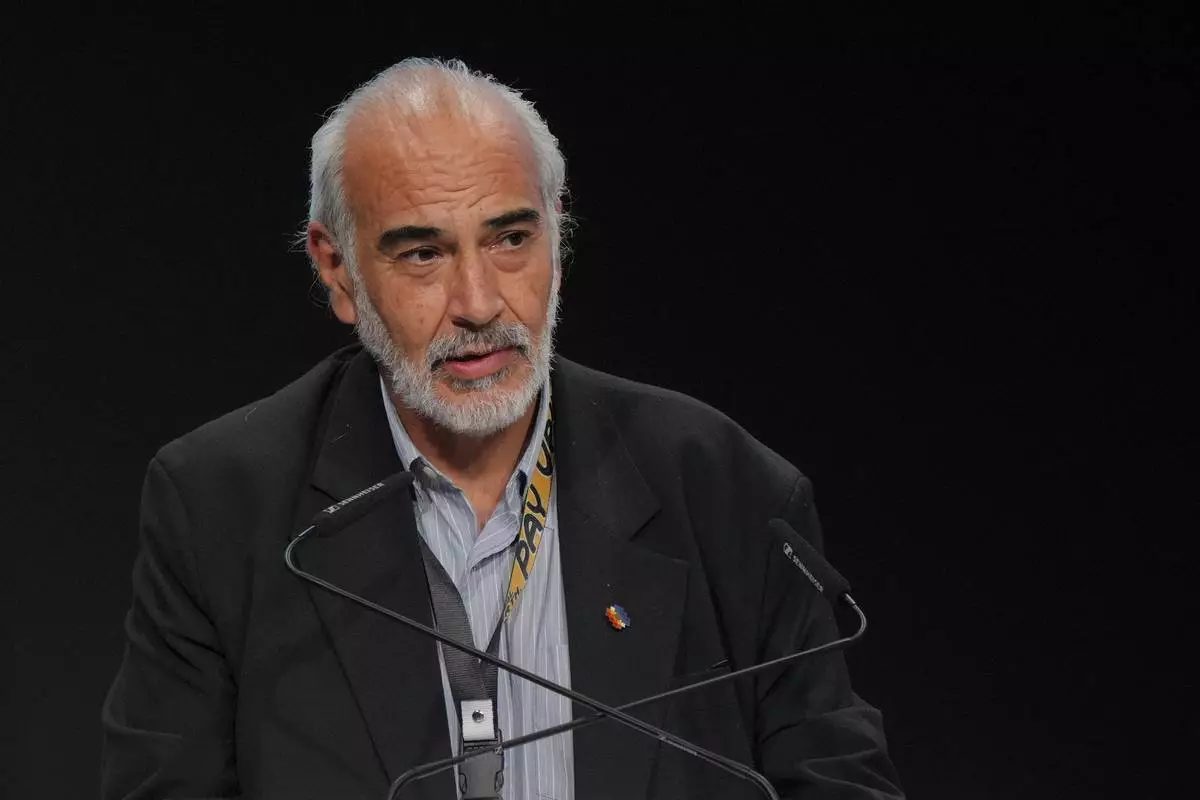

Bolivia's foreign policy director and chair of the Like-Minded Group negotiating bloc Diego Balanza called out developed countries in speech Tuesday, saying they have “squarely failed to provide committed support to developing countries.”

“A significant share of loans has adverse implications for the macroeconomic stability of developing countries,” Balanza said.

The G20's mention of the need for strong climate finance and especially the replenishment of the International Development Association gives a boost to negotiators in Baku, ECCO's Bergamaschi said.

“G20 Leaders have sent a clear message to their negotiators at COP29: do not leave Baku without a successful new finance goal,” United Nations climate secretary Simon Stiell said. “This is an essential signal, in a world plagued by debt crises and spiraling climate impacts, wrecking lives, slamming supply chains and fanning inflation in every economy.”

But analysts and activists said they were worried because the G20 statement did not repeat the call for a transition away from fossil fuels, a hard-fought concession at last year's climate talks.

Veteran climate talks analyst Alden Meyer of the European think tank E3G said the watering down of the G20 statement on fossil fuel transition is because of pressure by Russia and Saudi Arabia. He said it is "just the latest reflection of the Saudi wrecking ball strategy" at climate meetings.

There's also debate in Baku about whether to reiterate last year's statement calling for transition away from fossil fuels.

Associated Press reporter Sibi Arasu contributed.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

People arrive for the day at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

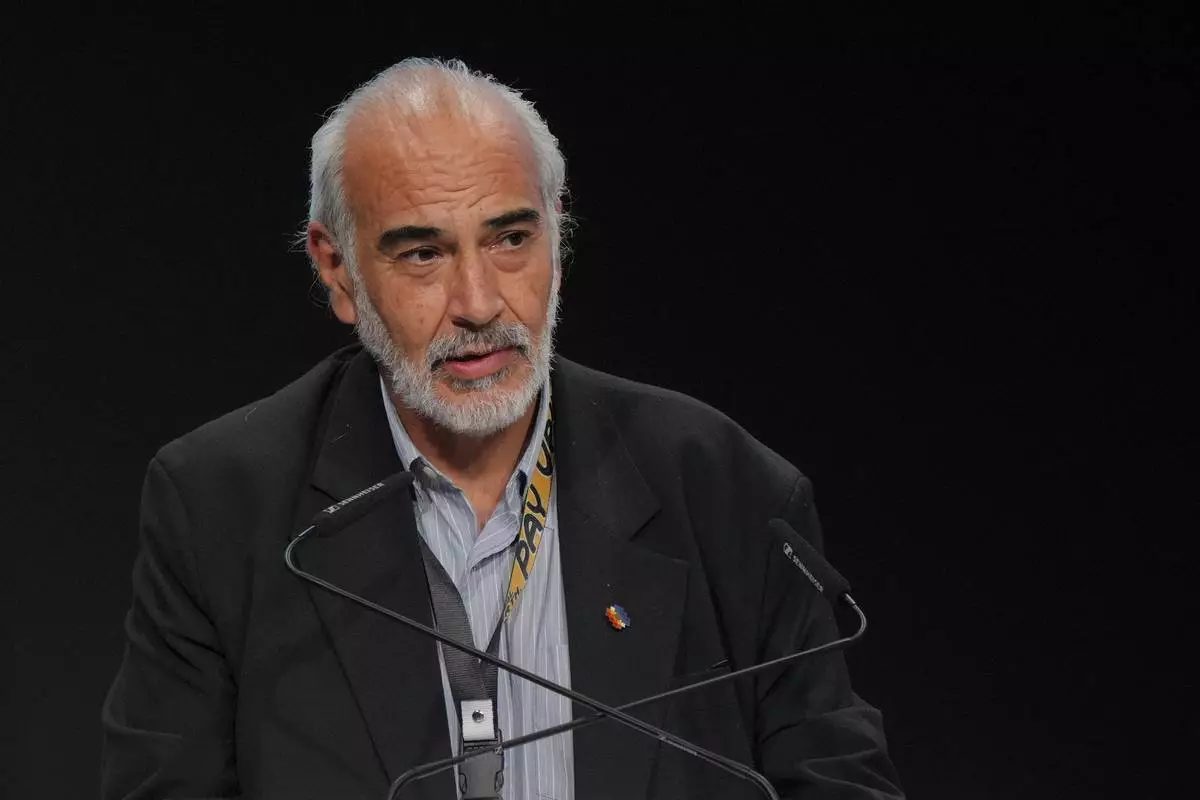

Bolivia foreign policy director and Like-Minded Group chair Diego Balanza speaks during a plenary session at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

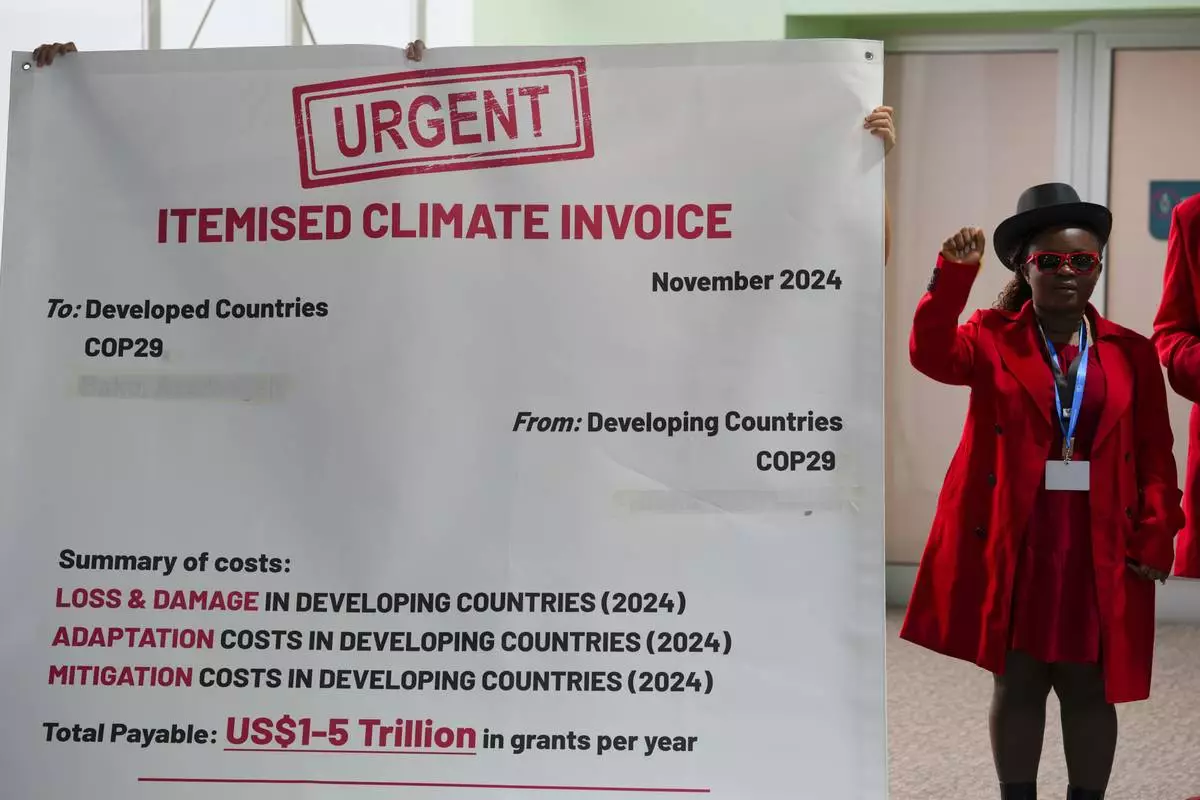

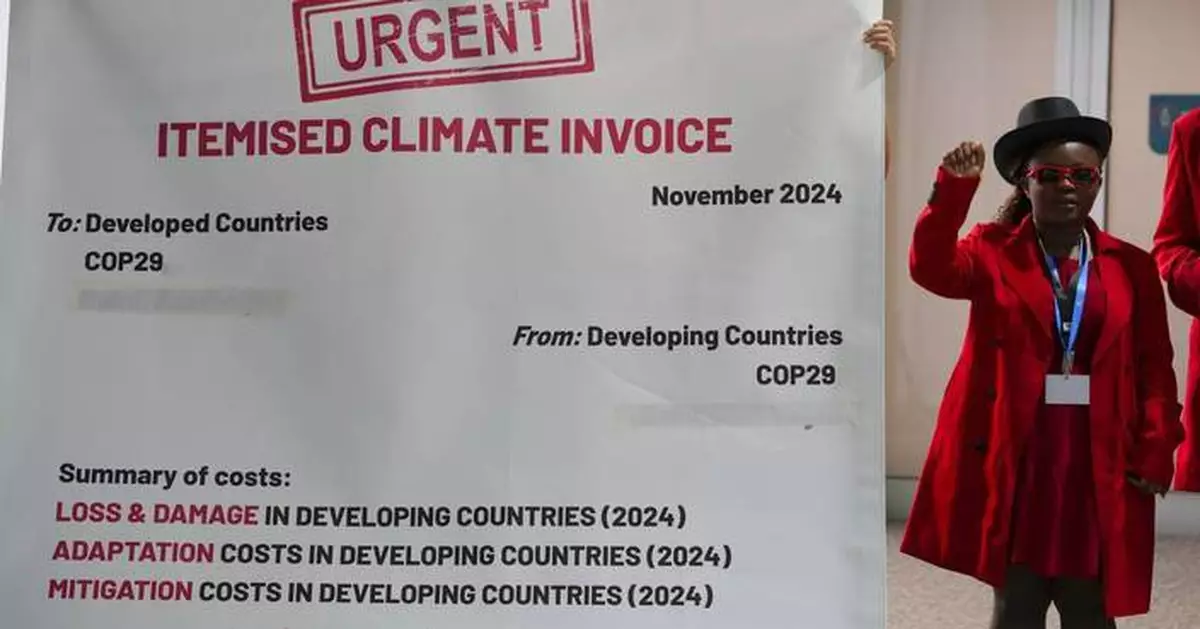

Activists participate in a demonstration for climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

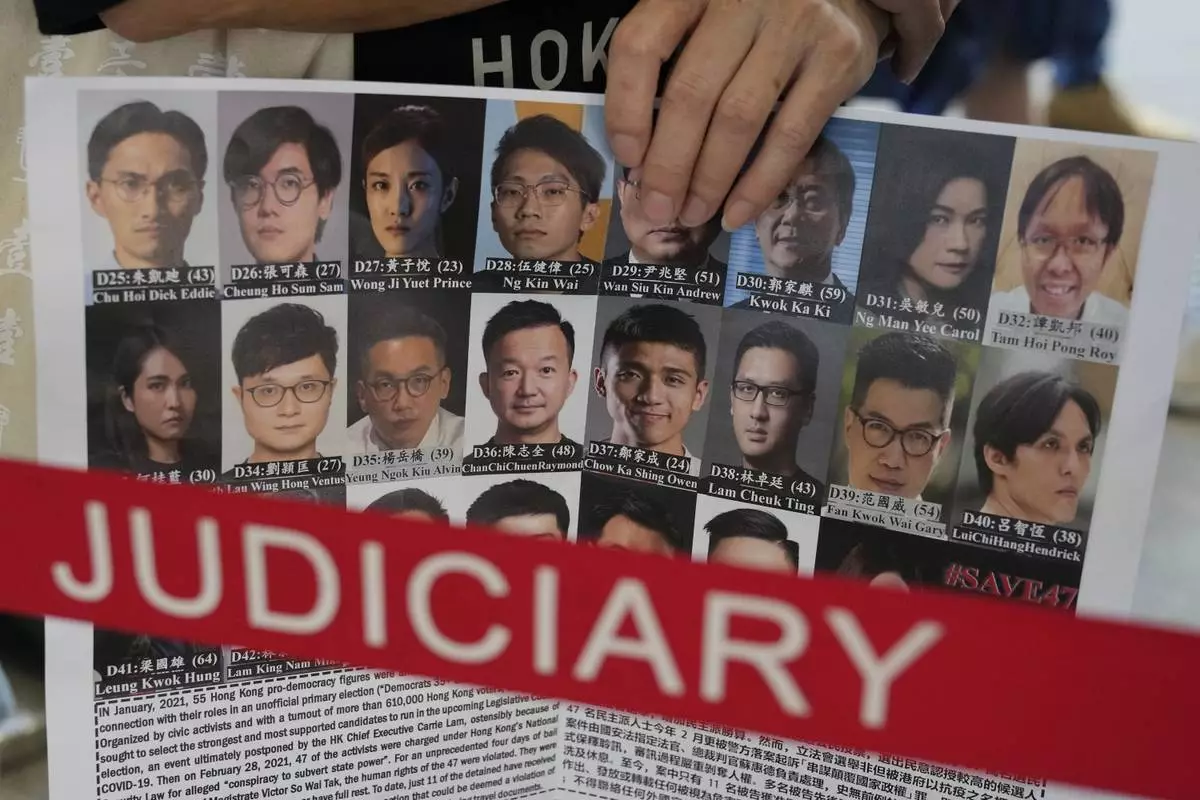

HONG KONG (AP) — Forty-five ex-lawmakers and activists were sentenced to four to 10 years in prison Tuesday in Hong Kong’s biggest national security case under a Beijing-imposed law that crushed a once-thriving pro-democracy movement.

They were prosecuted under the 2020 national security law for their roles in an unofficial primary election. Prosecutors said their aim was to paralyze Hong Kong’s government and force the city’s leader to resign by aiming to win a legislative majority and using it to block government budgets indiscriminately.

The unofficial primary held in July 2020 drew 610,000 voters, and its winners had been expected to advance to the official election. Authorities canceled the official legislative election, however, citing public health risks during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Legal scholar Benny Tai, whom the judges called the mastermind, received the longest sentence of 10 years. The judges said the sentences had been reduced for defendants who said they were unaware the plan was unlawful.

However, the court said the penalties were not reduced for Tai and former lawmaker Alvin Yeung because they are lawyers who were “absolutely adamant in pushing for the implementation of the Scheme.”

In the judgment posted online, the judges wrote that Tai essentially “advocated for a revolution” by publishing a series of articles over a period of months that traced his thinking, even though in a letter seeking a shorter sentence Tai said the steps were “never intended to be used as blueprint for any political action.”

Two of the 47 original defendants were acquitted earlier this year. The rest either pleaded guilty or were found guilty of conspiracy to commit subversion. The judges said in their verdict that the activists’ plans to effect change through the unofficial primary would have undermined the government’s authority and created a constitutional crisis.

The judges rejected the reasoning from some defendants that the scheme would never have materialized, stating that “all the participants had put in every endeavor to make it a success."

The judges highlighted that a great deal of time, resources and money were devoted to the organization of the primary election.

“When the Primary Election took place on the 10 and 11 July, no one had remotely mentioned the fact that Primary Election was no more than an academic exercise and that the Scheme was absolutely unattainable,” the judgment read. “In order to succeed, the organizers and participants might have hurdles to overcome, that however was expected in every subversion case where efforts were made to overthrow or paralyze a government.”

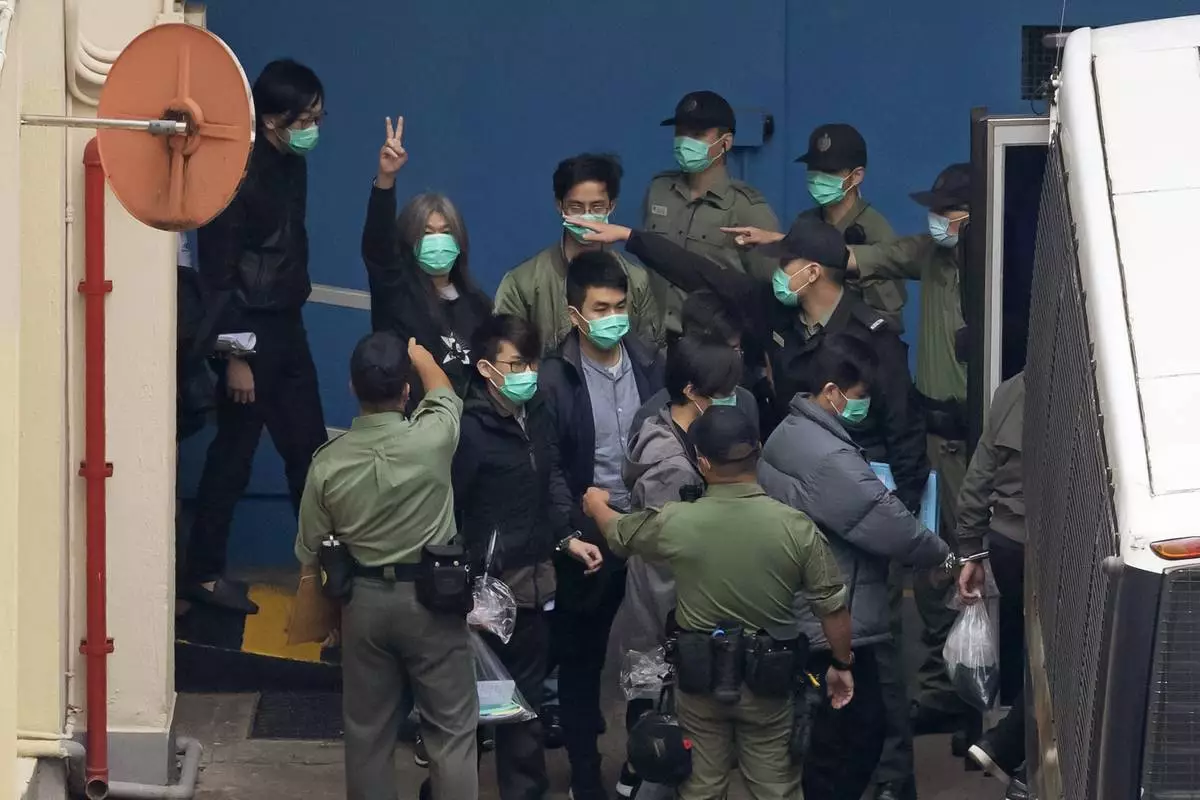

Some of the defendants waved at their relatives in the courtroom after they were sentenced.

Gwyneth Ho, a journalist-turned-activist who was jailed for seven years, said “our true crime for Beijing is that we were not content with playing along in manipulated elections” on her Facebook page.

“We dared to confront the regime with the question: Will democracy ever be possible within such a structure? The answer was a complete crackdown on all fronts of society," she wrote.

Chan Po-ying, wife of defendant Leung Kwok-hung, told reporters she wasn’t shocked when she learned her husband received a jail term of six years and nine months. She said they were trying to use some of the rights granted by the city’s mini-constitution to pressure those who are in power to address the will of the people.

“This is an unjust imprisonment. They shouldn’t be kept in jail for one day,” said Chan, also the chair of the League of Social Democrats, one of the city’s remaining pro-democracy parties.

Emilia Wong, the girlfriend of Ventus Lau, said his jail term was within her expectations. She said the sentencing was a “middle phase” of history and she could not see the end point at this moment, but she pledged to support Lau as best as she could.

Philip Bowring, the husband of Claudia Mo, was relieved that the sentences were finally handed down.

Observers said the trial illustrated how authorities suppressed dissent following huge anti-government protests in 2019, alongside media crackdowns and reduced public choice in elections. The drastic changes reflect how Beijing’s promise to retain the former British colony’s civil liberties for 50 years when it returned to China in 1997 is increasingly threadbare, they said.

Beijing and Hong Kong governments insisted the national security law was necessary for the city's stability.

The sentencing drew criticism from foreign governments and human rights organizations.

The U.S. Consulate in Hong Kong said the U.S. strongly condemned the sentences for the 45 pro-democracy advocates and former lawmakers.

“The defendants were aggressively prosecuted and jailed for peacefully participating in normal political activity protected under Hong Kong’s Basic Law,” the statement said, referring to the city's mini-constitution.

Hong Kong Secretary for Security Chris Tang said in a news briefing that the sentences showed those committing national security crimes must be severely punished.

The subversion case involved pro-democracy activists across the spectrum. They include Tai, former student leader Joshua Wong and former lawmakers. Wong was sentenced to four years and eight months in jail. Young activist Owen Chow was given the second-longest jail term, seven years and nine months.

Most of them have already been detained for more than three and a half years before the sentencing. The separations pained them and their families.

More than 200 people stood in line in rain and winds Tuesday morning for a seat in the court, including one of the acquitted defendants, Lee Yue-shun. Lee said he hoped members of the public would show they care about the court case.

“The public's interpretation and understanding has a far-reaching impact on our society's future development,” he said.

Wei Siu-lik, a friend of convicted activist Clarisse Yeung, said she arrived at 4 a.m. even though her leg was injured. “I wanted to let them know there are still many coming here for them,” she said.

Thirty-one of the activists entered guilty pleas and had better chances of getting reduced sentences. The law authorizes a range of sentences depending on the seriousness of the offense and the defendant’s role in it, from under three years for the least serious to 10 years to life for people convicted of “grave” offenses.

People leave the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, following the sentencing in national security case. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Lee Yue-shun, former pro-democracy district councilor who was cleared of the charge of the national security case, leaves the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, following the sentencing in national security case. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Chan Po-ying, wife of Leung Kwok-hung, one of the defendants in the national security case, leaves the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, after the sentencing. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Representatives from various consulates wait in line outside the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, ahead of the sentencing in national security case. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Representatives from various consulates wait in line outside the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, ahead of the sentencing in national security case. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

People wait outside the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, ahead of the sentencing in national security case. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

People wait outside the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, ahead of the sentencing in national security case. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

People wait outside the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, ahead of the sentencing in national security case. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Police officers stand guard outside the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

People wait outside the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, ahead of the sentencing in national security case. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Armed police officers stand guard outside the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

Police officers stand guard outside the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

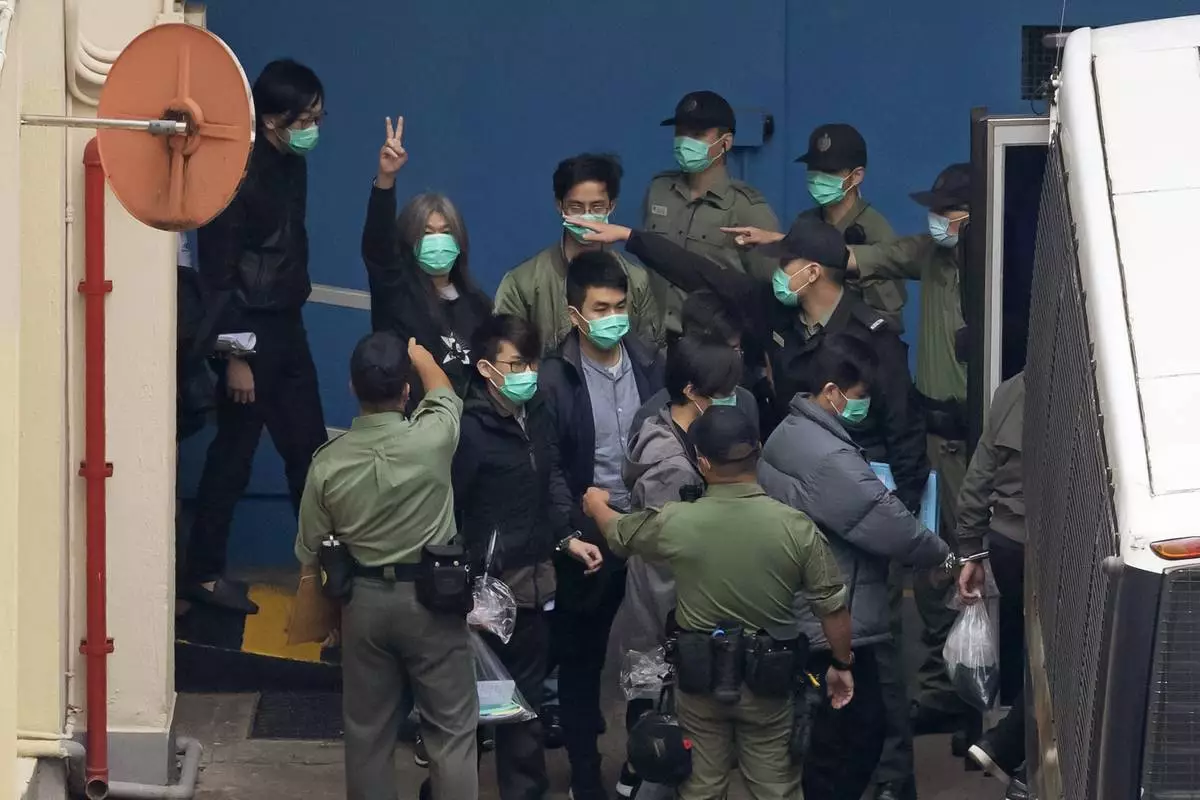

FILE - Former lawmaker Leung Kwok-hung, known as "Long Hair," second left, shows a victory sign as some of the 47 pro-democracy activists are escorted by Correctional Services officers to a prison van in Hong Kong, March 4, 2021. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung, File)

FILE- Hong Kong activists and supporters march with a banner which reads " Unite now in solidarity with the Hong Kong 47 and other political prisoners" during a protest commemorating the 10th anniversary of the 2014 umbrella movement and the fifth anniversary of the anti-extradition law amendment bill movement in Taipei, Taiwan, June 9, 2024. (AP Photo/Chiang Ying-ying, File)

FILE- A pro-democracy activist known as "Grandma Wong" protests outside the West Kowloon courts in a cordoned off area set up by police as closing arguments open in Hong Kong's largest national security trial of 47 pro-democracy figures in Hong Kong, Nov. 29, 2023. (AP Photo/Louise Delmotte, File)

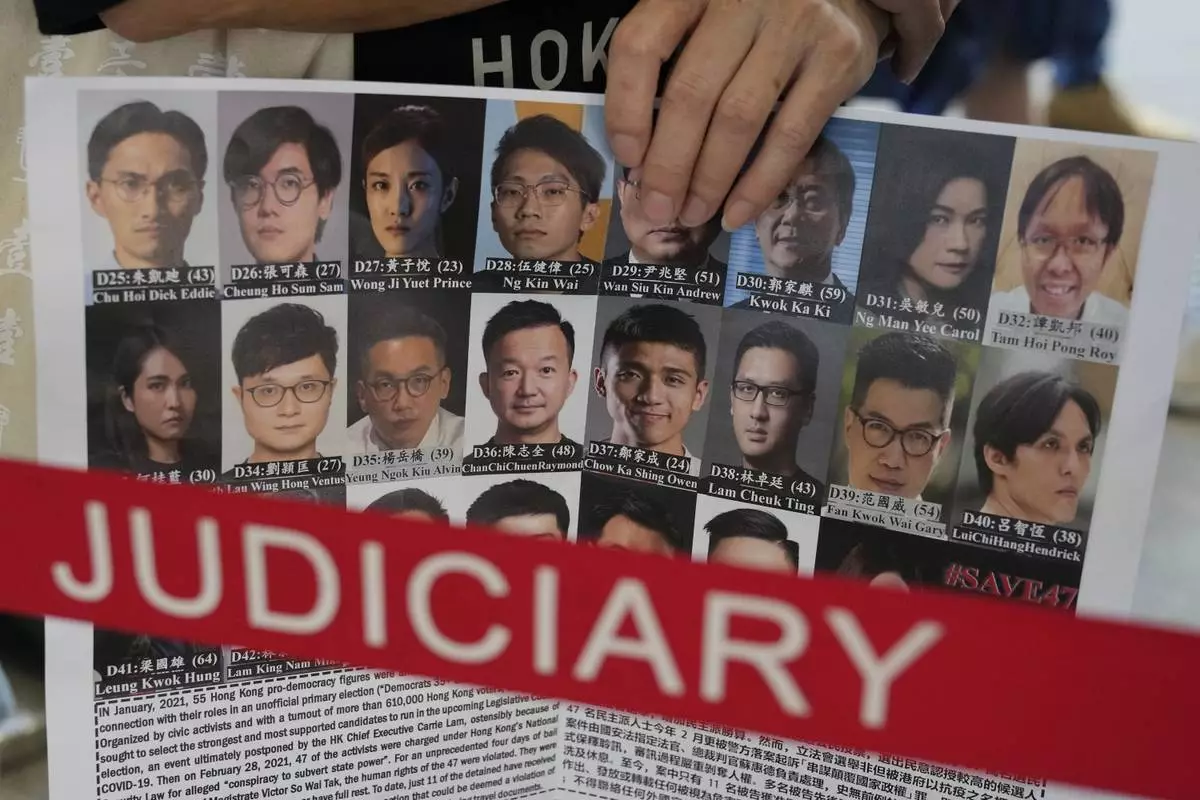

FILE - A supporter holds a placard with the photos of some of the 47 pro-democracy defendants outside a court in Hong Kong, on July 8, 2021. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung, File)

A Correctional Services Department vehicle arrives at the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, ahead of the sentencing in national security case. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

A Correctional Services Department vehicle arrives at the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, ahead of the sentencing in national security case. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

People wait outside the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, ahead of the sentencing in national security case. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)

People wait outside the West Kowloon Magistrates' Courts in Hong Kong Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, ahead of the sentencing in national security case. (AP Photo/Chan Long Hei)