Tied for the lead with three holes left in an exhausting season for Rory McIlroy, he launched a pitching wedge toward the 16th green in Dubai and barked out desperate instructions.

“Go! Go! Go!" he urged the golf ball as it descended over the water.

Click to Gallery

Rory McIlroy of Northern Ireland hits off the first tee in the final round of World Tour Golf Championship in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Sunday, Nov. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

Rory McIlroy of Northern Ireland plays his second shot on the 9th hole in the final round of World Tour Golf Championship in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Sunday, Nov. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

Rory McIlroy of Northern Ireland reacts after winning the World Tour Golf Championship in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Sunday, Nov. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

Rory McIlroy of Northern Ireland celebrates after winning the World Tour Golf Championship, in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Sunday, Nov. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

Rory McIlroy of Northern Ireland poses with the DP World Tour Championship trophy and the Race to Dubai trophy after winning the World Tour Golf Championship in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Sunday, Nov. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

Rory McIlroy of Northern Ireland poses with his wife, Erica Stoll and Daughter, Poppy McIlroy alongside the trophies after winning the World Tour Golf Championship in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Sunday, Nov. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

It dropped in front of the flag, a foot from the hole, a shot that carried him to another victory in the season-ending DP World Tour Championship, his fourth win of the year, and a sixth title as No. 1 on the European tour.

By all accounts, it was a great year.

But it's different when those trophies — and a big one that was missing — belong to McIlroy.

“I'm going to look back on 2024 and I'm going to have four wins,” he said.

Two were in Dubai, at the start and finish of the year. One was at Quail Hollow for the fourth time. The other was the most fun — the Zurich Classic with close friend Shane Lowry, followed by McIlroy belting out Journey's “Don't Stop Believin'” at a post-tournament party.

“But I know that my 2024 is going to be defined — at least by others — by the tournaments that I didn't win as much as the tournaments I did,” he said.

Such are the expectations for McIlroy. He has to come to accept them, or he wouldn't have brought that up without any prompting. This is what happens with greatness. And this is a level of play that remarkably doesn't get enough credit.

Yes, he was tops in Europe for the third consecutive time, and sixth overall. That leaves him only two away from matching the record of Colin Montgomerie, who had the advantage of never leaving Europe to play two tours.

But go back to Oct. 4, 2009. McIlroy tied for second in the Dunhill Links Championship and moved to No. 19 in the world at age 20. He has not been outside the top 20 ever since, an astonishing streak of 15 years and counting.

Phil Mickelson at 16 years and 30 weeks is the only player to have a longer run in the top 20.

Even so, the only streak that matters when the conversation turns to McIlroy is his 10 straight years without a major. That's what gives him pause when he rates his year. He was three holes away from a U.S. Open title at Pinehurst No. 2 until he missed short par putts on the 16th and 18th holes, and Bryson DeChambeau saved par with an exquisite bunker shot to beat him.

McIlroy has been desperate to win the Masters for the career Grand Slam. At this point, any major would do. Who could have imagined his last major would have come at age 25?

There also was disappointment on losing a late lead to a fast-charging Rasmus Hojgaard in the Irish Open at Royal County Down, right when all of Northern Ireland was ready to celebrate McIlroy winning on home soil.

Billy Horschel beat him in a playoff at Wentworth. McIlroy's dynamic charge in Paris drowned with a wedge into the water at the Olympics. Play long enough at that level and those outcomes are bound to happen.

A great year? For anyone else, sure.

“Unfortunately for Rory, I think everybody looks at the glass half-empty,” Lowry said. "I look at it glass half-full. He's had an amazingly consistent year. I've had a consistent year, but he's had consistent top-3 finishes — mine are top 15s.

“He probably should have won the U.S. Open — let's be honest, and he'd say that himself — but he didn't,” Lowry said. “I think he is more determined than ever to come out firing next year, and obviously the Masters will be on the forefront.”

It was more than DeChambeau pipping him at Pinehurst that gave McIlroy pause. He won four times and actually dropped one spot in the world ranking to No. 3, behind Scottie Scheffler and Xander Schauffele.

Scheffler has no equal at the moment with eight wins, including the Masters, The Players Championship and Olympic gold. Schauffele won two majors at the PGA Championship and British Open.

“They certainly separated themselves from the pack this year,” McIlroy said. “I'm obviously aware of that, and it only makes me more motivated to try to emulate what they did this year.”

McIlroy said he got choked up at the end of his season at the mention of tying the late Seve Ballesteros with a sixth Order of Merit. Ballesteros is the soul of European golf, and that's not likely to change no matter how many more titles McIlroy wins.

But there was more to the emotion. The end of any season tends to bring that out, and this was a season like no other.

Off the course, McIlroy has been involved in negotiations between the PGA Tour and the Saudi backers of LIV Golf, and his desire to reunite with LIV defectors occasionally has put him at odds with other players.

Far more personal was the shock announcement in May he had filed for divorce, and then disclosing a month later they had scrapped the divorce filing in a bid to save their marriage. His wife, Erica, and 4-year-old daughter Poppy celebrated with him in Dubai. Call it five wins for the year.

He played 27 times, a lot early in search of the right formula to be ready for the Masters, and a lot late because the European tour means a lot to him. He says he will scale back. He is not getting any younger. He is no less entertaining.

In light of it all, golf is a game. But that wedge was big. Winning was important. For such a tumultuous year, it was the ideal way for it to end.

“Yeah, it's been quite the year,” McIlroy said. “But you know, I'm super happy with where I am in my career and in my life. And I feel like everything’s worked out the way it was supposed to.”

AP golf: https://apnews.com/hub/golf

Rory McIlroy of Northern Ireland hits off the first tee in the final round of World Tour Golf Championship in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Sunday, Nov. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

Rory McIlroy of Northern Ireland plays his second shot on the 9th hole in the final round of World Tour Golf Championship in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Sunday, Nov. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

Rory McIlroy of Northern Ireland reacts after winning the World Tour Golf Championship in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Sunday, Nov. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

Rory McIlroy of Northern Ireland celebrates after winning the World Tour Golf Championship, in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Sunday, Nov. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

Rory McIlroy of Northern Ireland poses with the DP World Tour Championship trophy and the Race to Dubai trophy after winning the World Tour Golf Championship in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Sunday, Nov. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

Rory McIlroy of Northern Ireland poses with his wife, Erica Stoll and Daughter, Poppy McIlroy alongside the trophies after winning the World Tour Golf Championship in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, Sunday, Nov. 17, 2024. (AP Photo/Altaf Qadri)

BAKU, Azerbaijan (AP) — Just as a simple lever can move heavy objects, rich nations are hoping another kind of leverage — the financial sort — can help them come up with the money that poorer nations need to cope with climate change.

It involves a complex package of grants, loans and private investment, and it's becoming the major currency at annual United Nations climate talks known as COP29.

But poorer nations worry they’ll get the short end of the lever: not much money and plenty of debt.

Meanwhile, half a world away in Brazil, leaders of the 20 most powerful economies issued a statement that among other things gave support to strong financial aid for climate for poor nations and the use of leverage financial mechanisms. That was cheered by climate analysts and advocates.

Money is the key issue in Baku, where negotiators are working on a new amount of cash for developing nations to transition to clean energy, adapt to climate change and deal with weather disasters. It’ll replace the current goal of $100 billion annually — a goal set in 2009.

Negotiators are fighting over three big parts of the issue: How big the numbers are, how much is grants or loans, and who pays. The how big question is the toughest to negotiate and will likely be resolved only after the first two are solved, COP29 lead negotiator Yalchin Rafiyev told The Associated Press in an interview Tuesday.

“There are interlinkages of the elements. That’s why having one of them agreed could unlock the other one,” Rafiyev said.

It's like the first domino falling leading to another, he said.

In these negotiations, rich potential donor nations have been reluctant to offer a starting figure to negotiate from. So Rafiyev said the conference presidency is putting the pressure on them, telling “the developed countries that the figure should be fair and ambitious, corresponding to the needs and priorities of the world.”

India’s junior environment minister Kirti Vardhan Singh, who is at the Baku talks, said that “the global south are bearing a huge financial burden.”

“This is severely limiting our capacity to meet our developmental needs,” he said.

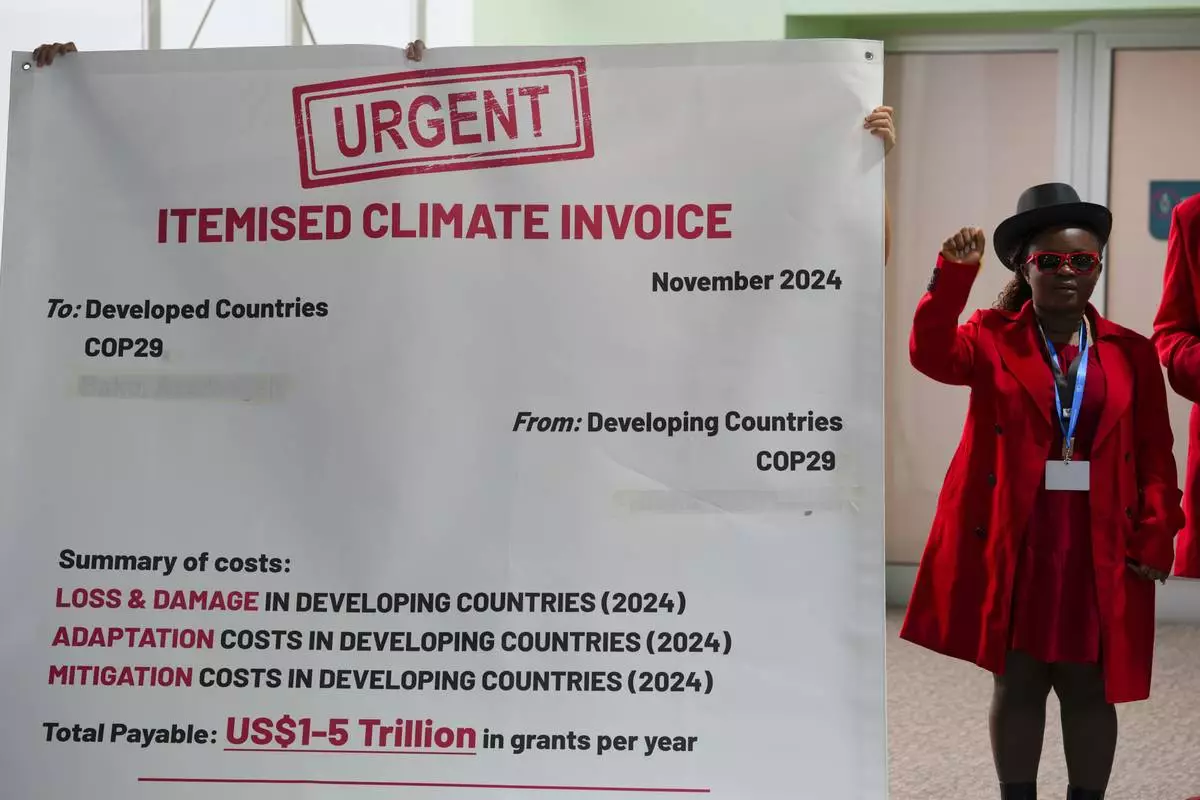

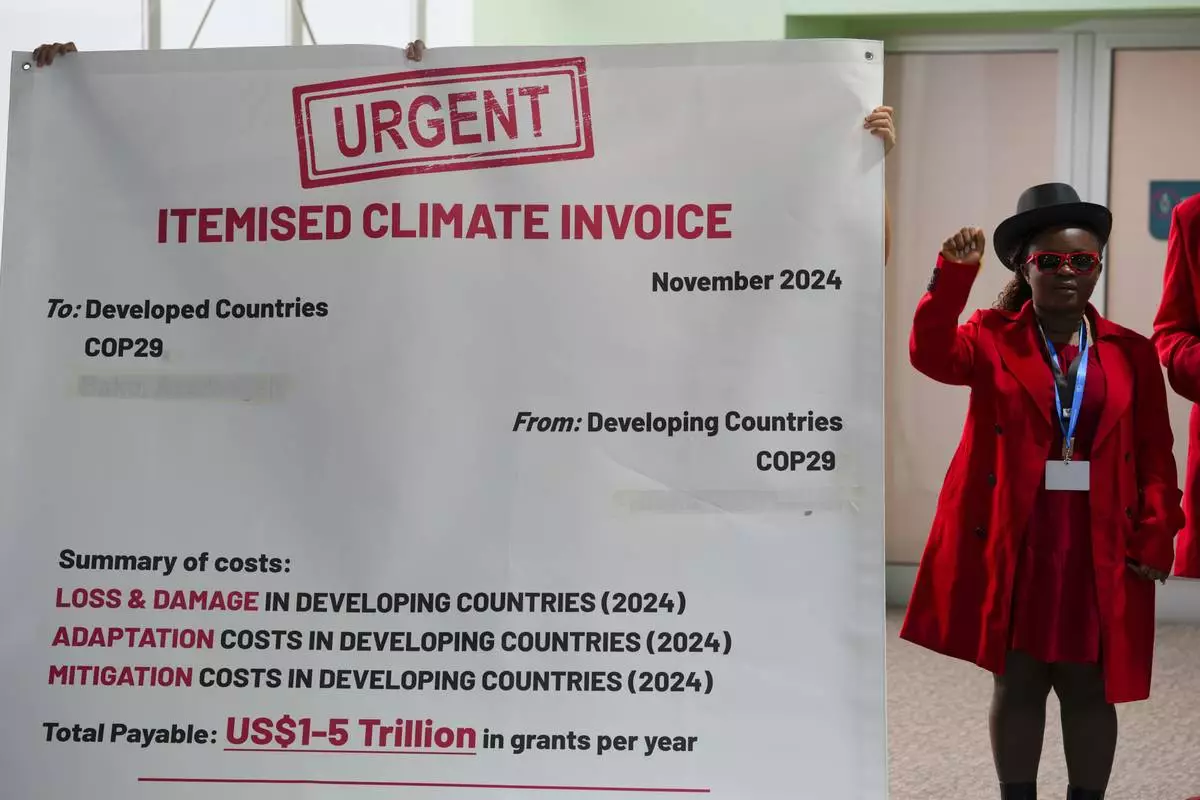

Experts put the number needed for climate finance at $1 trillion, while developing nations have said they'll need $1.3 trillion. But negotiators are talking about different types of money as well as amounts.

So far rich nations have not quite offered a number for the core of money they could provide. But the European Union is expected to finally do that and it will likely be in the $200 to $300 billion a year range, Linda Kalcher, executive director of the think tank Strategic Perspectives, said Tuesday. It might be even as much as four times the original $100 billion, said Luca Bergamaschi, co-founding director of the Italian ECCO think tank.

But there's a big difference between $200 billion and $1.3 trillion. That can be bridged with “the power of leverage," said Avinash Persaud, climate adviser for the Inter-American Development Bank.

When a country gives a multilateral development bank like his $1, it could be used with loans and private investment to get as much as $16 in spending for transitioning away from dirty energy, Persaud said. When it comes to spending to adapt to climate change, the bang for the buck, is a bit less, about $6 for every dollar, he said.

But when it comes to compensating poor nations already damaged by climate change — such as Caribbean nations devastated by repeated hurricanes — leverage doesn't work because there's no investment and loans. That's where straight-out grants could help, Persaud said.

Whatever the form of the finance, Ireland’s environment minister Eamon Ryan said it would be “unforgivable” for developed countries to walk away from negotiations in without making a firm commitment toward developing ones.

“We have to make an agreement here,” he said. "We do have to provide the finance, particularly for the developing countries, and to give confidence that they will not be excluded, that they will be center stage.”

If climate finance comes mostly in the form of loans, it means more debt for nations that are already drowning in it, said Michai Robertson, climate finance negotiator for the Alliance of Small Island States.

“All of these things are just nice ways of saying more debt,” Robertson said.

His organization argues that most of the $1.3 trillion it seeks should be in grants and very low-interest and long-term loans that are easier to pay back. Only about $400 billion should be in leveraged loans, Robertson said.

Leverage from loans “will be a critical part of the solution,” said United Nations Environment Programme Director Inger Andersen. But so must grants and so must debt relief, she added.

Rohey John, Gambia's environment minister, said the absence of a financial commitment from rich nations suggests “they are not interested in the development of the rest of the mankind.”

“Each and every day we wake up to a crisis that will wipe out a whole community or even a whole country, to a crime that we never committed," she said.

Ministers giving their national statements also came out with fighting words.

“Our children, our elderly, our women, our girls, our Indigenous people, our youth deserve better,” said St. Kitts and Nevis Climate Minister Joyelle Clarke. “Let us be seized by a desire for better."

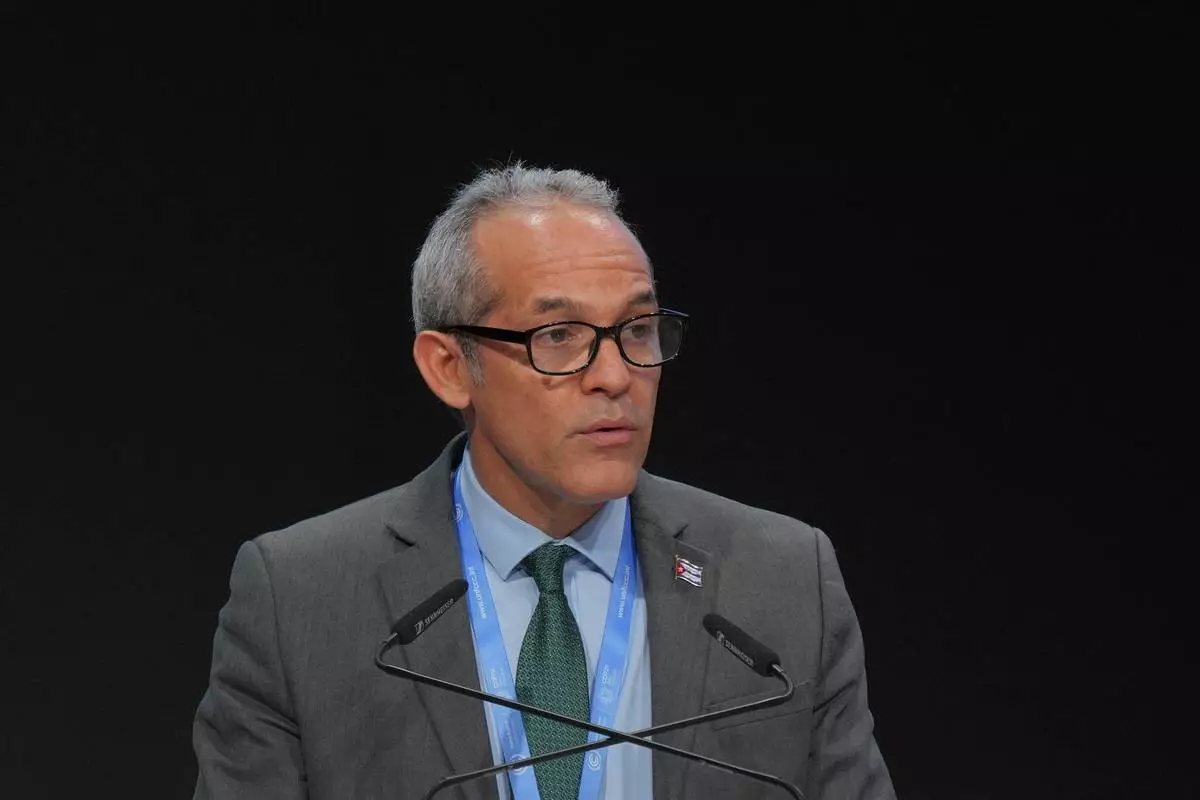

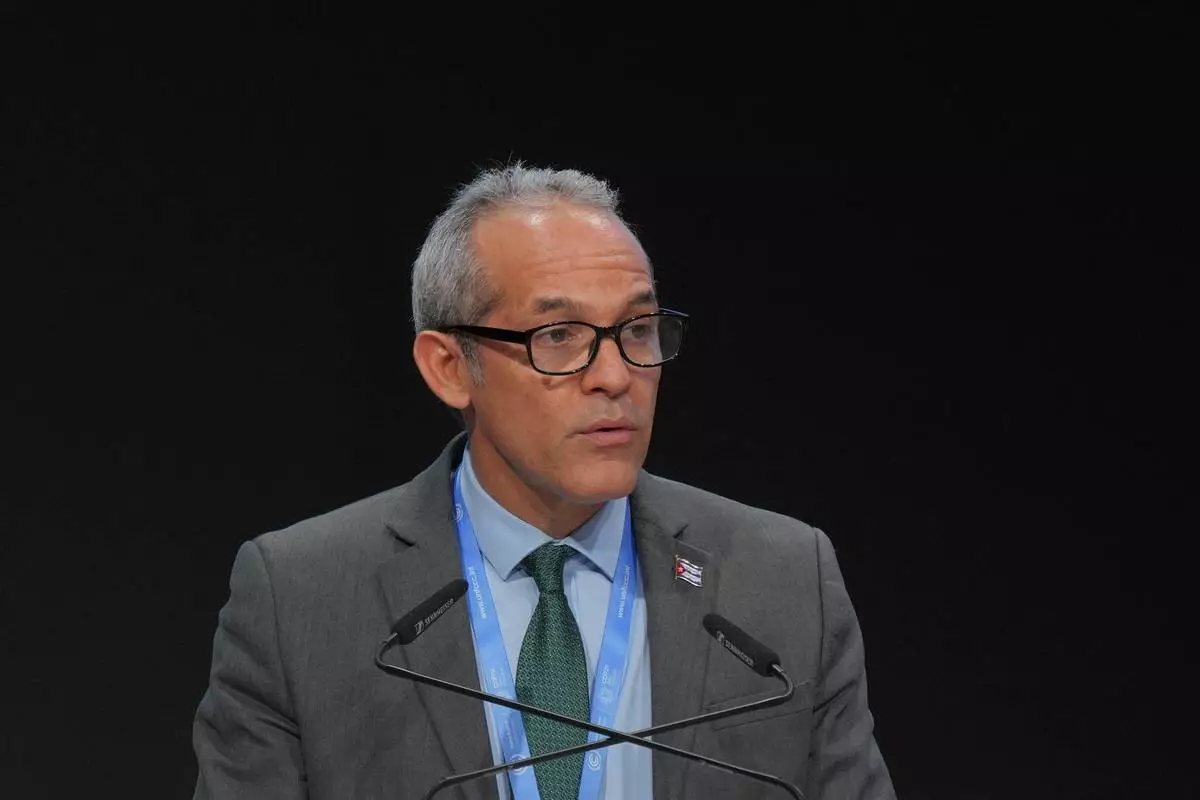

Cuban environment minister Armando Rodriguez Batista urged countries not to “favor death over life.”

The G20's mention of the need for strong climate finance and especially the replenishment of the International Development Association gives a boost to negotiators in Baku, ECCO's Bergamaschi said.

“G20 Leaders have sent a clear message to their negotiators at COP29: do not leave Baku without a successful new finance goal,” United Nations climate secretary Simon Stiell said. “This is an essential signal, in a world plagued by debt crises and spiraling climate impacts, wrecking lives, slamming supply chains and fanning inflation in every economy.”

Analysts and activists said they were also worried because the G20 statement did not repeat the call for a transition away from fossil fuels, a hard-fought concession at last year's climate talks.

Veteran climate talks analyst Alden Meyer of the European think tank E3G said the watering down of the G20 statement on fossil fuel transition is because of pressure by Russia and Saudi Arabia. He said it is "just the latest reflection of the Saudi wrecking ball strategy" at climate meetings.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

People listen to speeches during a plenary session at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Cuba Environment Minister Armando Rodriguez Batista speaks during a plenary session at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

St. Kitts and Nevis Climate Minister Joyelle Clarke speaks during a plenary session at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Yalchin Rafiyev, Azerbaijan's COP29 lead negotiator, speaks during an interview with The Associated Press at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

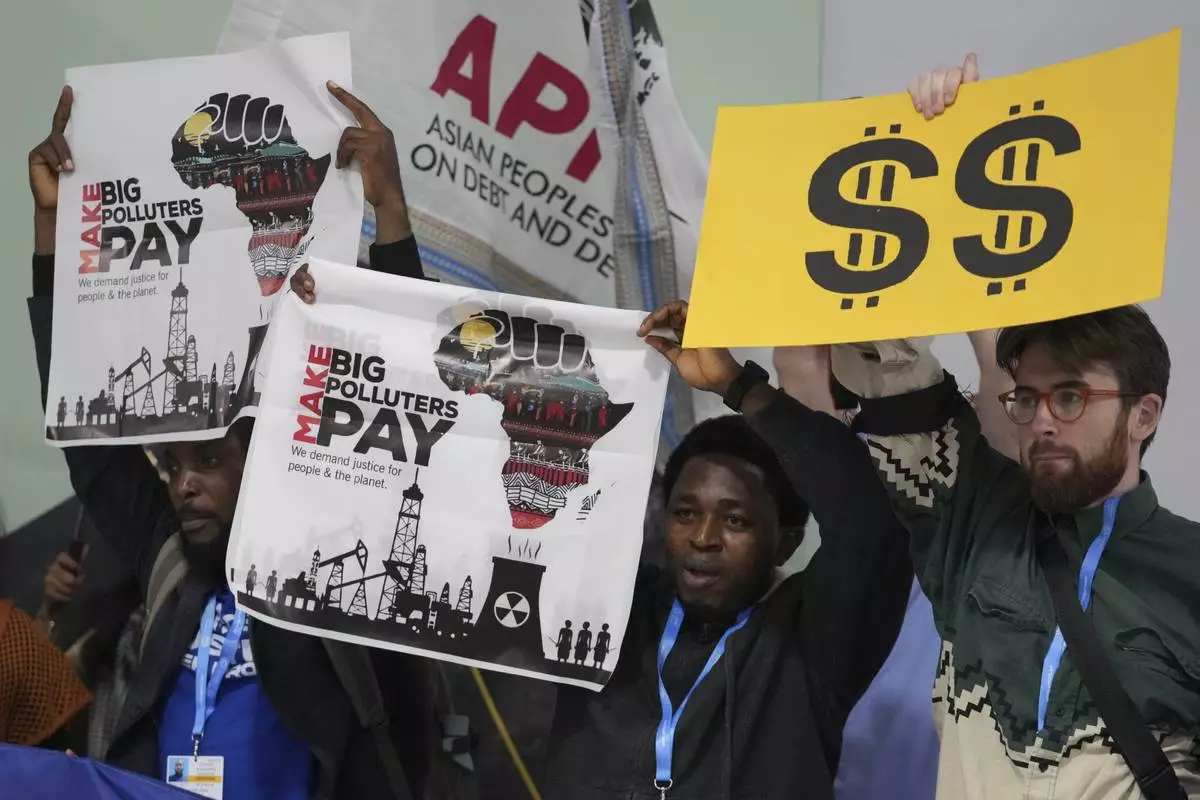

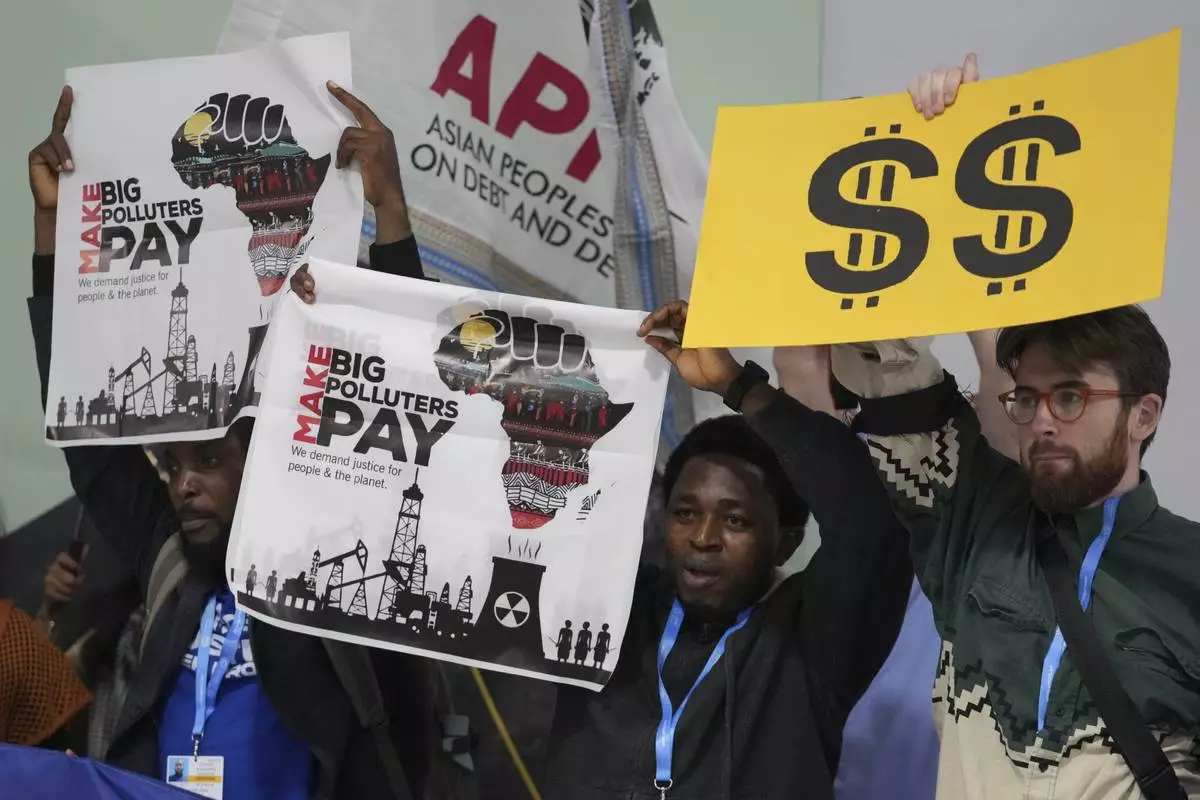

Activists participate in a demonstration for climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool)

People arrive for the day at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

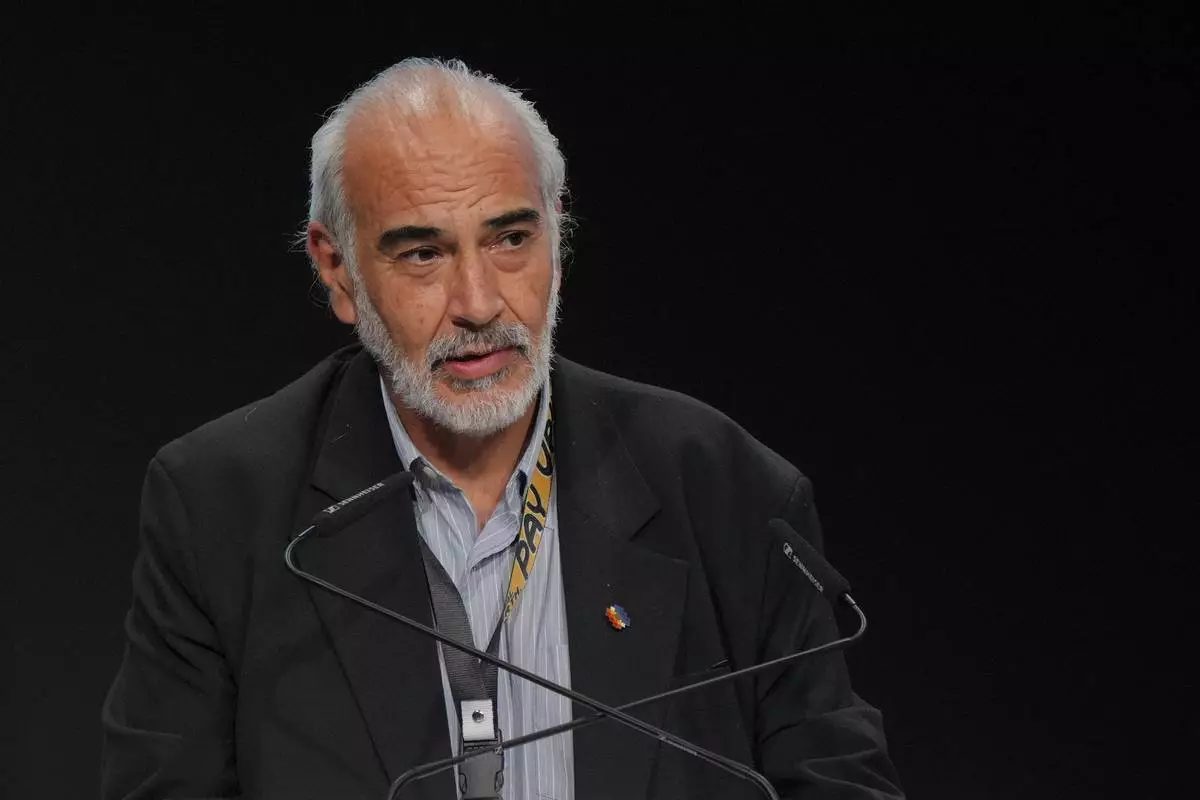

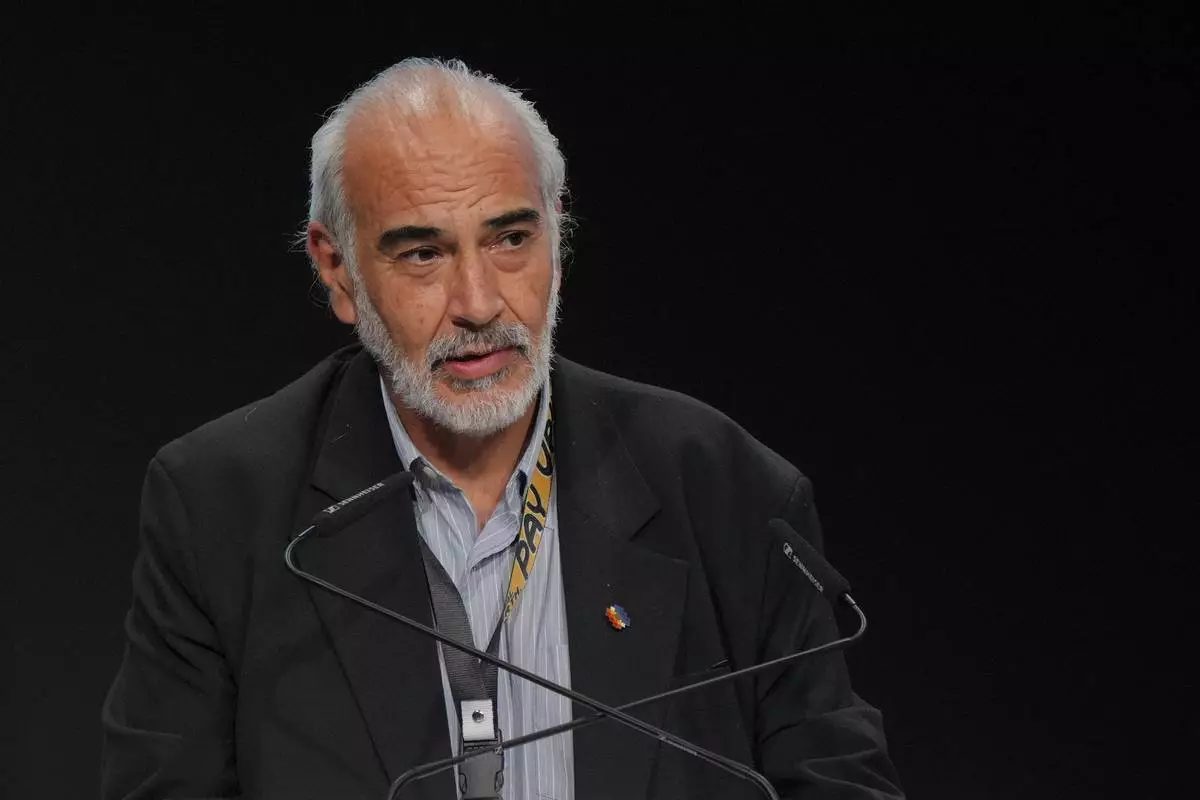

Bolivia foreign policy director and Like-Minded Group chair Diego Balanza speaks during a plenary session at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Activists participate in a demonstration for climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Tuesday, Nov. 19, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)