LONDON (AP) — Indigenous leaders from the Wampis Nation in Peru are urging lawmakers at the House of Commons in London to ban international banks' support for Amazon oil activities they say harm their ancestral rainforests.

HSBC bank, based in the United Kingdom, JPMorgan Chase in the United States and Santander in Spain helped finance the state-owned oil company Petroperu as it sought to upgrade a coastal refinery. The plant processes crude oil from a 680-mile (1,094-kilometer) pipeline that runs through rainforest.

In the last decade there have been dozens of leaks along the pipeline.

After the meetings, Baroness Ritchie of Downpatrick raised the issue in the House of Lords and in an interview Friday said the banks’ actions were “deplorable.”

“We’ve been conserving our forest for over 7,000 years,” Pamuk Teófilo Kukush Pati, a Wampis leader, told The Associated Press.

Now their fishing waters have been badly polluted, he said, and “there is no guarantee of life ... we are in a very grave situation.”

“Most alarming is the fact we find out that various banks fund Petroperu,” said Tsanim Evaristo Wajai Asamat, another Wampis leader. "And these things are happening all across the Amazon.”

The banks acted as “bookrunners” on a $1 billion bond offering for the refinery work in 2021, first reported by the U.K. nonprofit Bureau of Investigative Journalism. When banks act as bookrunners, they advertise the bonds to their customers and use their reputation to give investors confidence. Financial data provider Dealogic estimates each bank made $583,000 in fees.

A spokeswoman for Santander bank said via email that the company followed all relevant environmental regulations and does a careful analysis before backing companies that operate in the Amazon. A JPMorgan spokeswoman said Indigenous rights are a fundamental consideration across their business. A spokeswoman for HSBC said in a statement that it places restrictions on backing projects in the Amazon.

In the last decade, there were 89 leaks from the pipeline, Petroperu said in an email. It said only two were caused by equipment failure — criminals or natural forces caused the rest. Petroperu has spent more than $180 million cleaning up the last decade’s oil spills, it said.

More than 15,000 Wampis live on some 5,000 square miles (13,000 square kilometers) of forest and wetland in northern Peru. Their territory is home to hundreds of species of fish and rare birds.

The people made headlines in 2015 when they declared an autonomous government, in part to protect their environment. The government of Peru does not recognize it.

According to Petroperu's bond prospectus for the refinery project, which provides transparency to investors, bond buyers faced financial risks “relating to the effects of oil leaks on local and indigenous communities.” There could be protests, fines, compensation and negative publicity, it warned, and Indigenous communities had “taken hostile measures against our facilities and installations on various occasions.”

The prospectus also said there were criminal investigations being conducted by Peruvian prosecutors over oil spills that included former Petroperu executives. Petroperu has since denied that people at its executive level are being investigated, saying that two lower-level employees were among those of interest to prosecutors. The company said via email that it's cooperating with the investigation.

The year after the bond deal, in 2022, Peruvian regulators penalized Petroperu with 66 fines, including for new oil spills along the pipeline. The three banks did business with Petroperu again last year, providing advice as the oil company sought to change the terms of its debt.

The Wampis are unhappy about illegal logging and mining on their territory as well. They were joined in London by several delegations pressing for a proposed law that would make it a crime for British businesses to harm the environment and threaten human rights.

Delegations from Colombia, Liberia and Mexico met with Baroness Ritchie, then with senior officials at both the U.K. Foreign Office and Environment Department.

“You need the corporate law,” she said, “to ensure that this is stopped. It's to do with respect. You should be respecting people if you are mining or doing oil exploration in their countries.”

Jesús Javier Thomas González, from northern Mexico, spoke of a ten-year battle with a mining company listed on the London Stock Exchange that he said illegally occupied and devastated their land.

The company has “economic and political influence in Mexico that is huge,” he said. It's a good corporate citizen in the UK, he said, “but in Mexico they behave in a different way.”

A U.K. government spokesman said British firms should always act to avoid environmental harms, and its approach to tackling those that don't is under constant review.

__

Grattan reported from Bogota, Colombia.

__

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Indigenous leaders from the Wampis Nation in Peru, from left, Pamuk Teofilo Kukush Pati, Tsanim Evaristo Wajai Asamat and Jesus Javier Thomas Gonzalez, from Mexico, pose in St. Stephen's Hall in London, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

Indigenous leaders from the Wampis Nation in Peru, Pamuk Teofilo Kukush Pati, left, and Tsanim Evaristo Wajai Asamat, back right, arrive the House of Parliament in London, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

Indigenous leaders from the Wampis Nation in Peru, Tsanim Evaristo Wajai Asamat, left, and Pamuk Teofilo Kukush Pati, pose inside the Westminster Hall in London, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Kin Cheung)

BAKU, Azerbaijan (AP) — A new draft of a deal on cash to curb and adapt to climate change released Friday afternoon at the United Nations climate summit pledged $250 billion by 2035 from wealthy countries to poorer ones. The amount pleases the countries who will be paying, but not those on the receiving end.

The amount is more than double the previous goal of $100 billion a year set 15 years ago, but it's less than a quarter of the number requested by developing nations struck hardest by extreme weather. But rich nations say the number is about the limit of what they can do, say it's realistic and a stretch for democracies back home to stomach.

It struck a sour note for developing countries, which see conferences like this one as their biggest hope to pressure rich nations because they can't attend meetings of the world's biggest economies.

"Our expectations were low, but this is a slap in the face,” said Mohamed Adow, from Power Shift Africa. “No developing country will fall for this. They have angered and offended the developing world.”

The proposal came down from the top, the presidency of U.N. climate talks — called COP29 — in Baku, Azerbaijan. Delegations from numerous countries, analysts and advocates were kept in the dark about the draft until it dropped more than a half a day later than promised, prompting grumblings about how this conference was being run.

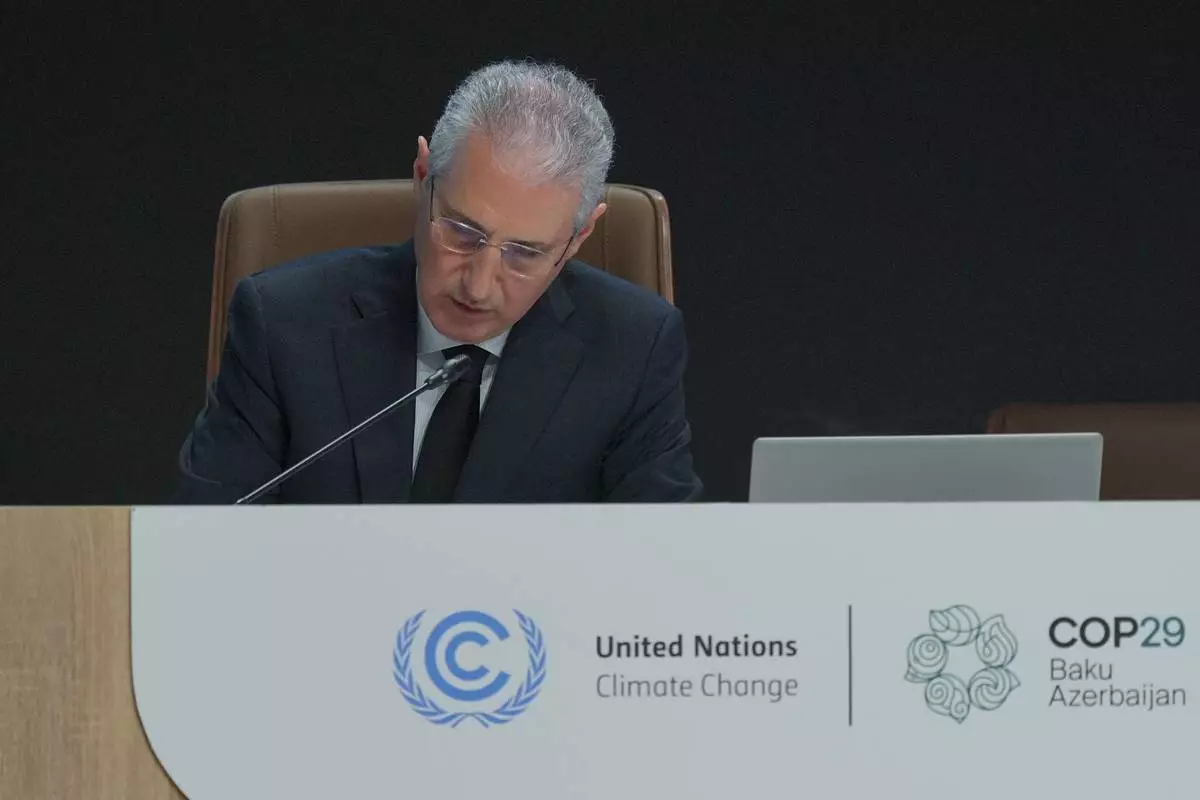

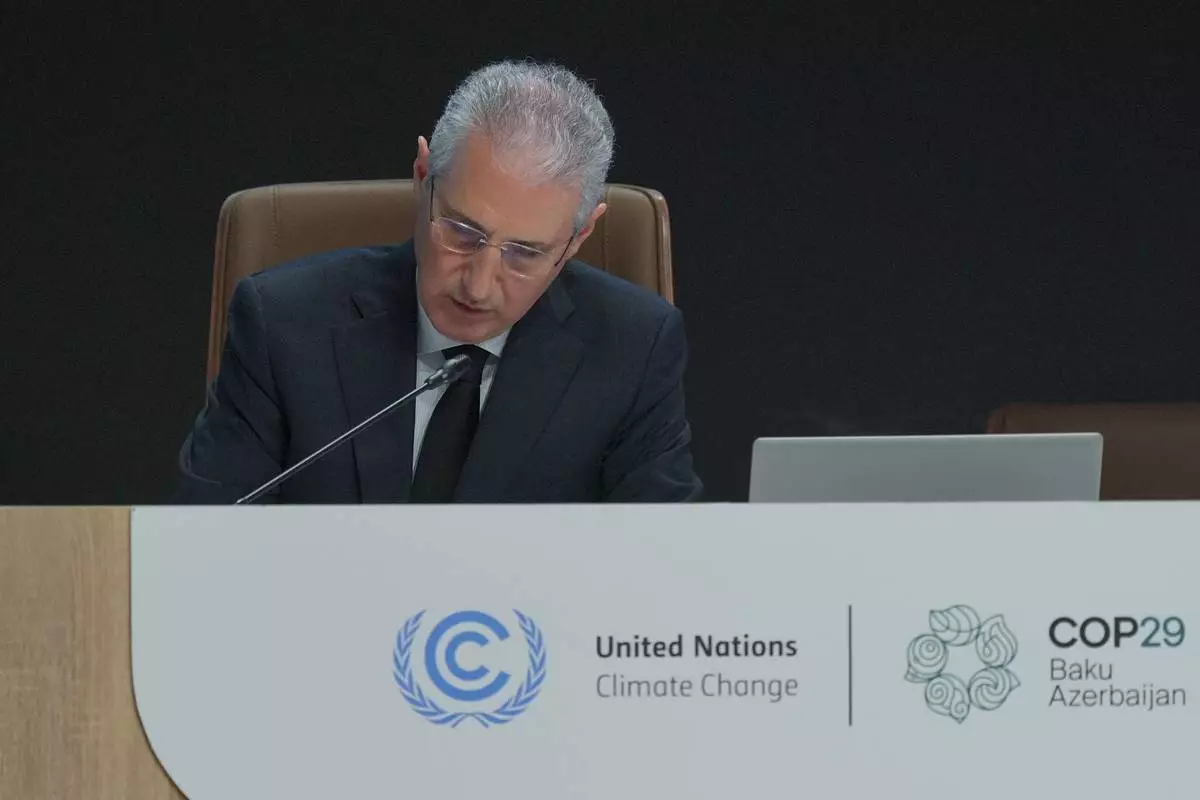

COP29 lead negotiator Yalchin Rafiyev, Azerbaijan's deputy foreign minister, said the presidency hopes to push countries to go higher than $250 billion, saying “it doesn't correspond to the our fair and ambitious goal. But we will continue to engage with the parties.”

This proposal, which is friendly to the viewpoint of Saudi Arabia, is not a take-it-or-leave-it option, but likely only the first of two or even three proposals, said Climate Analytics CEO Bill Hare, a veteran negotiator.

“We’re in for a long night and maybe two nights before we actually reach agreement on this,” Hare said.

Just like last year's initial proposal, which was soundly rejected, this plan is “empty” on what climate analysts call “mitigation” or efforts to reduce emissions from or completely get off coal, oil and natural gas, Hare said.

The frustration and disappointment at the proposed $250 billion figure was palpable on Friday afternoon.

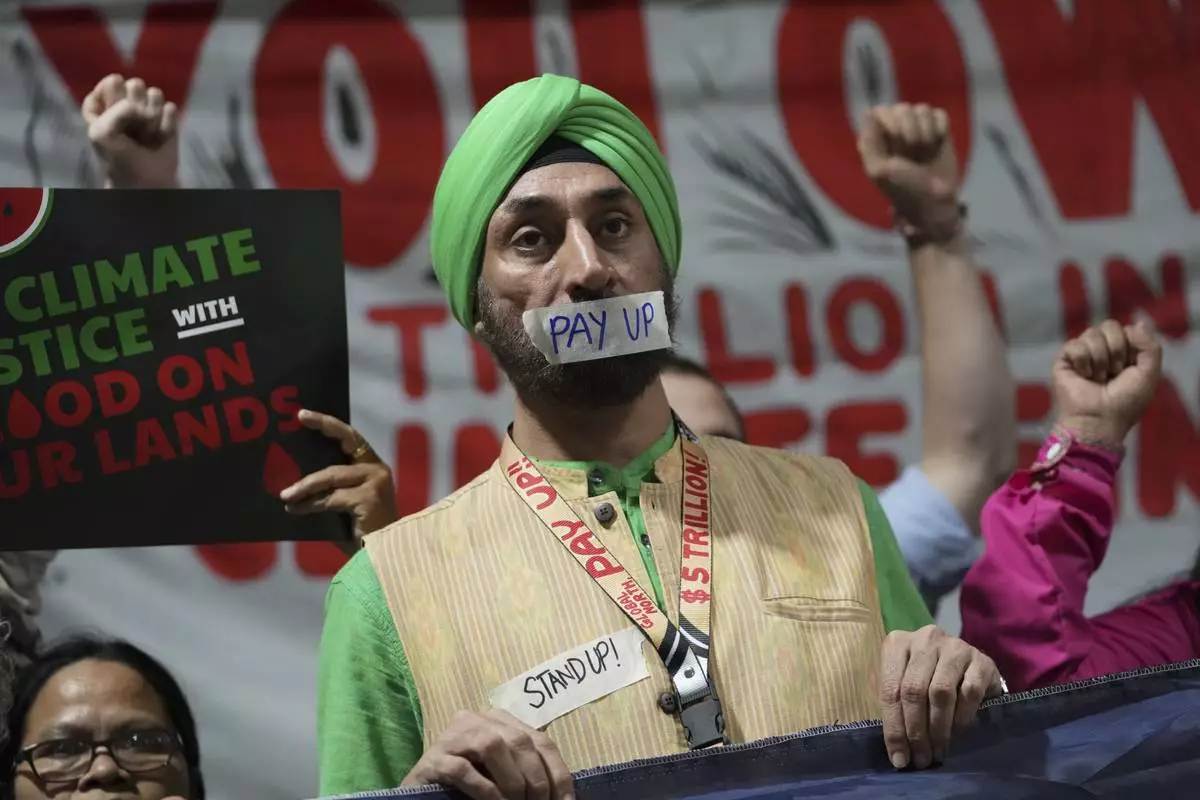

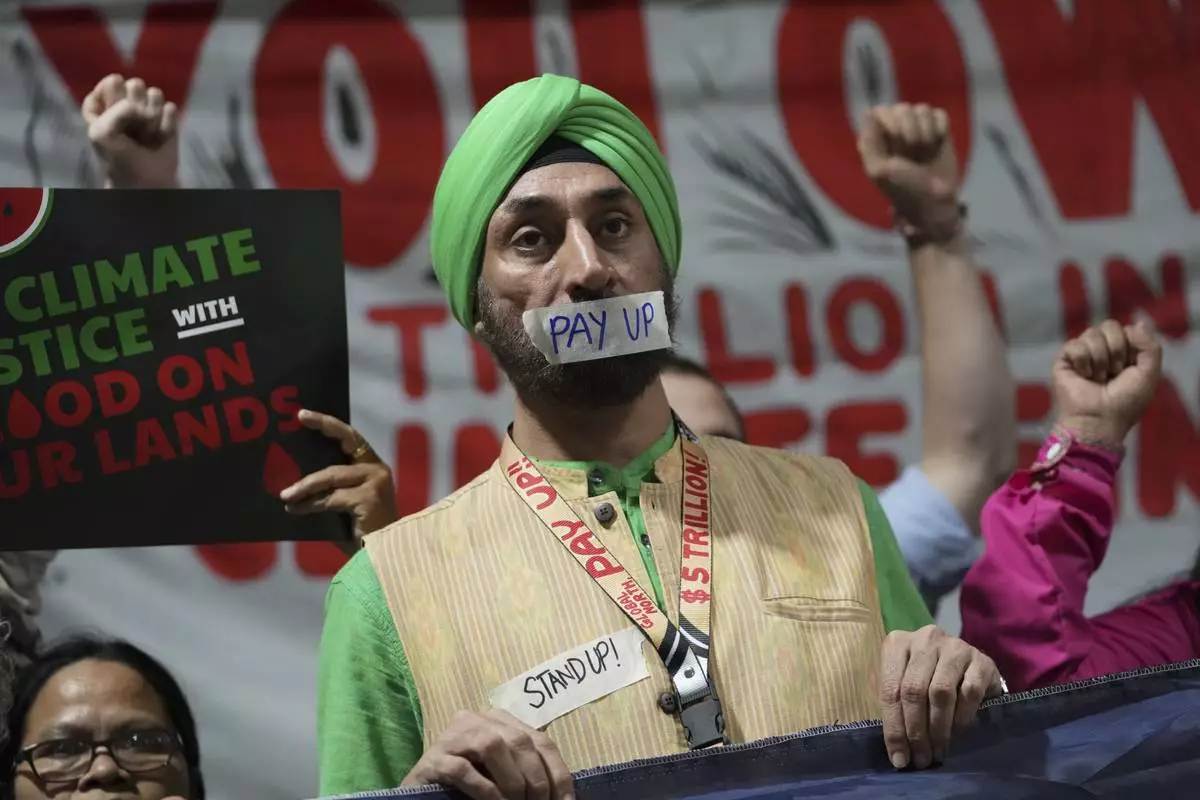

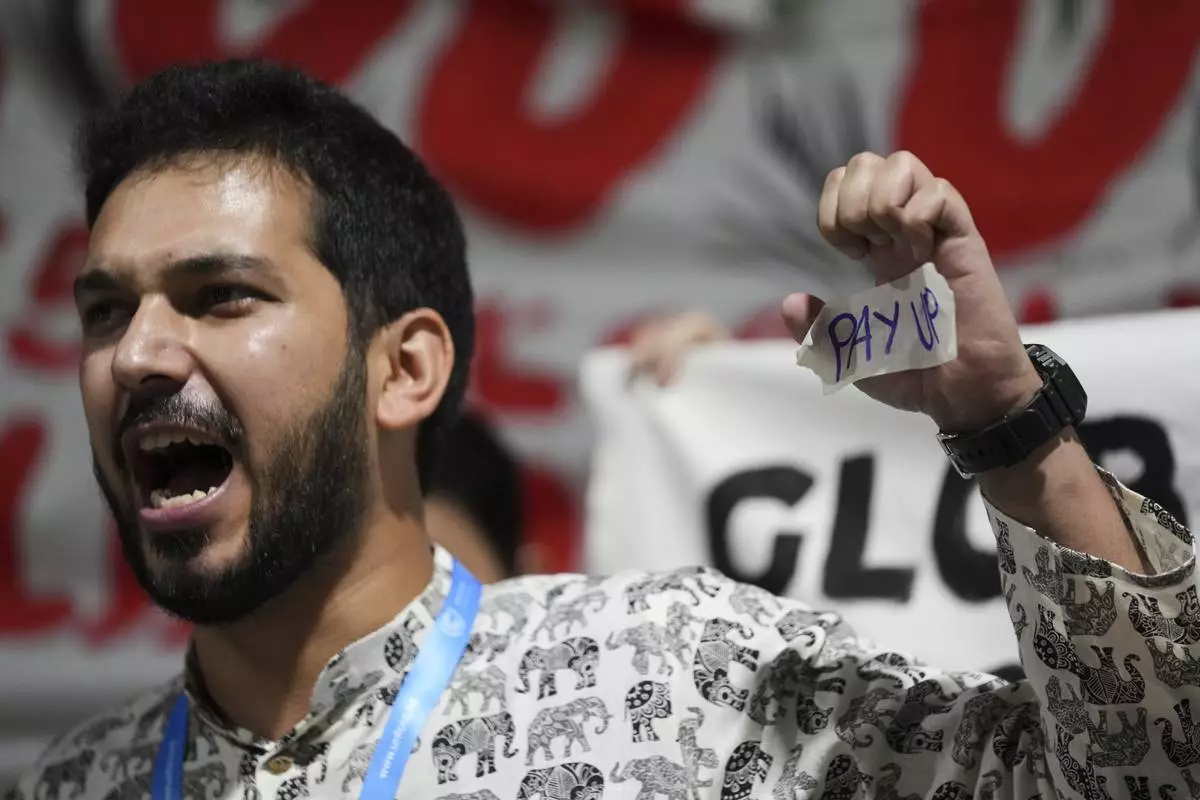

“It is a disgrace that despite full awareness of the devastating climate crises afflicting developing nations and the staggering costs of climate action — amounting to trillions — developed nations have only proposed a meagre $250 billion per year," said Harjeet Singh of the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty.

That amount, which goes through the year 2035, is basically the old $100 billion year goal with 6% annual inflation, said Vaibhav Chaturvedi a climate policy analyst with New Delhi-based Council on Energy, Environment and Water.

Experts put the need at $1.3 trillion for developing countries to cover damages resulting from extreme weather, help those nations adapt to a warming planet and wean themselves from fossil fuels, with more generated by each country internally.

The amount in any deal reached at COP negotiations — often considered a “core” — will then be mobilized or leveraged for greater climate spending. But much of that means loans for countries drowning in debt.

Singh said the proposed sum — which includes loans and lacks a commitment to grant-based finance — adds “insult to injury.”

Iskander Erzini Vernoit, director of Moroccan climate think-tank Imal Initiative for Climate and Development, said “the EU and the U.S. and other developed countries cannot claim to be committed to the Paris Agreement while putting forward such amounts” of money.

Countries reached the Paris Agreement in 2015, pledging to keep warming below 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit) since pre-industrial times. The world is now at 1.3 degrees Celsius (2.3 degrees Fahrenheit), according to the U.N.

Switzerland environment minister Albert Rösti said it was important that the climate finance number is realistic.

“I think a deal with a high number that will never be realistic, that will never be paid… will be much worse than no deal,” he said.

The United States' delegation offered a similar warning.

“It has been a significant lift over the past decade to meet the prior, smaller goal" of $100 billion, said a senior U.S. official. “$250 billion will require even more ambition and extraordinary reach" and will need to be supported by private finance, multilateral development banks — which are large international banks funded by taxpayer dollars — and other sources of finance, the official said.

A lack of a bigger number from European nations and the U.S. means that the “deal is clearly moving toward the direction of China playing a more prominent role in helping other global south countries,” said Li Shou of the Asia Society Policy Institute.

German delegation sources said it will be important to be in touch with China and other industrialized nations as negotiations press on into the evening.

Analysts said the proposed deal is the start of what could likely be more money.

“This can be a good down payment that will allow for further climate action in developing countries,” said Melanie Robinson, global climate program director at the World Resources Institute. “But there is scope for this to go above $250 billion.”

Rob Moore, associate director at E3G, said that whatever figure is agreed “will need to be the start and not the end" of climate cash promises.

"If developed countries can go further they need to say so fast to make sure we get a deal at COP29,” he said.

Associated Press journalists Ahmed Hatem and Aleksandar Furtula contributed to this report.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Demi Afasene, of Tuvalu, right, looks through a draft of a proposed deal for curbing climate change at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

An activist works on a display that reads in Portuguese persistir, that translates to persist, during the COP29 U.N. Climate SuRafiq Maqbool Nov. 22, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Rafiq Maqbool)

A person reads a draft of a proposed deal for curbing climate change during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Toeolesulusulu Cedric Schuster, Samoa environment minister, waits outside a room at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

A draft of a proposed deal for curbing climate change sits on a table at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

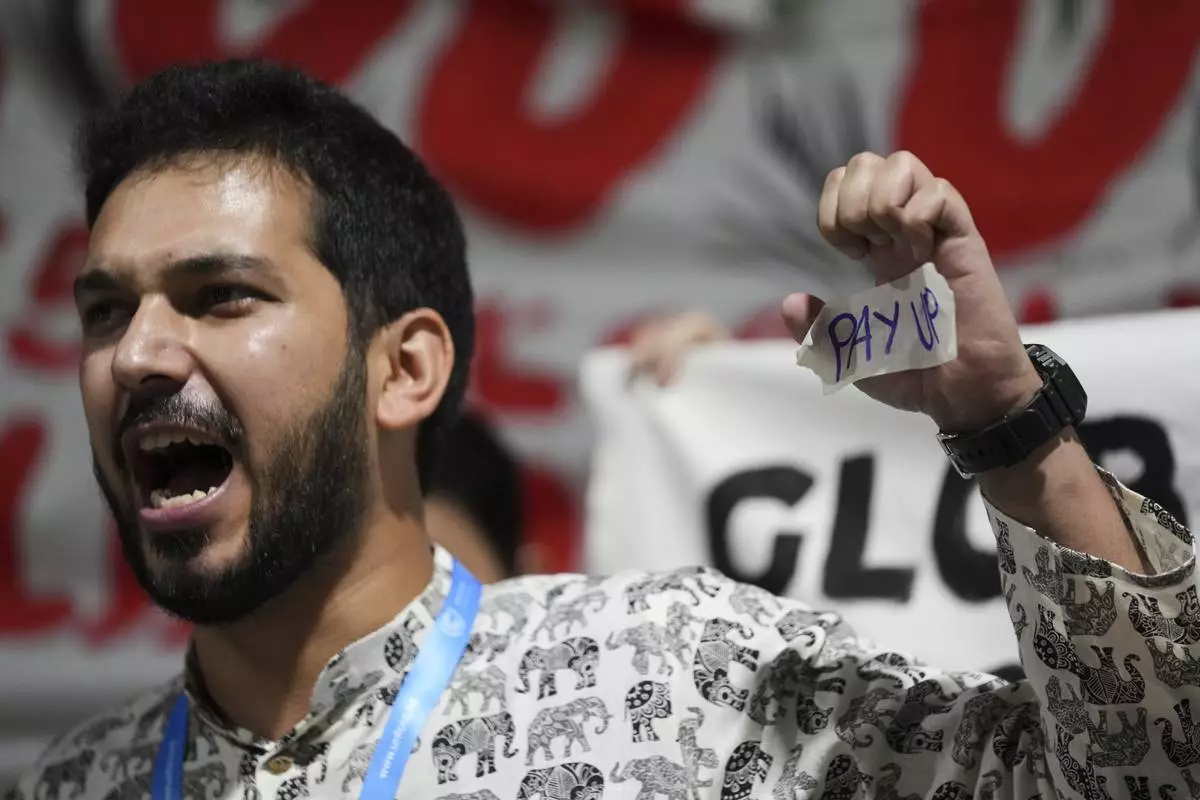

Activists participate in a demonstration for climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Albert Rosti, of Switzerland, speaks to members of the media at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Mukhtar Babayev, COP29 President, rehearses in the plenary at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

An activist displays "pay up" on his hand during a demonstration for climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Activists dressed as clowns participate in a demonstration for climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Activists participate in a demonstration for climate finance at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Activists participate in a demonstration for climate justice at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

The sun rises visible behind a transmission tower during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)

Dion George, South Africa environment minister, left, walks past a person in a dugong costume during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 22, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Peter Dejong)