BALI, Indonesia (AP) — Ketut Nita Wahyuni lifts her folded hands prayerfully to her forehead as a priest leads the temple gathering. The 11-year-old is preparing to perform the Rejang Dewa, a sacred Balinese dance.

The rituals are part of the two-week-long Ngusaba Goreng, a thanksgiving festival for a rich harvest. “Ngusaba” means gathering of the gods and goddesses.

Click to Gallery

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, looks at her phone with her father Nyoman Subrata sitting beside her, as mother Kadek Krisni, right, and sister Intan Wahyuni, in blue, dresses up her cousin Rina Lestianti before the Rejang Pucuk Hindu rituals at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, centre, performs the Rehang Dewa, a sacred Balinese dance, at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Kadek Krisni, left, walks with her daughter Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, to participate in a Hindu ceremony at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Nyoman Subrata, traditional chief of Geriana Kauh village, thanks villagers for participating in Ngusaba Goreng at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

A Hindu priest in trance points keris, traditional dagger, on his chest during a Hindu ceremony at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, left, participates in Rejang Pucuk at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, second left, stands with her friends as they participate in Rejang Pucuk in at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni is dressed up to participate in Rejang Pucuk Hindu ritual ceremony at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni is dressed up to participate in Rejang Pucuk Hindu ritual ceremony at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, looks at her phone with her father Nyoman Subrata sitting beside her, as mother Kadek Krisni, right, and sister Intan Wahyuni, in blue, dresses up her cousin Rina Lestianti before the Rejang Pucuk Hindu rituals at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Intan Wahyuni applies makeup for her younger sister Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, before participating in Rejang Pucuk Hindu rituals at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Sari gives an offering during Ngusaba Goreng, a thanksgiving festival for a rich harvest, at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Nyoman Subrata, traditional chief of Geriana Kauh village, carries a rooster used in rituals for Ngusaba Goreng festival at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Kadek Krisni, left, tries on a headgear for size on her daughter Kadek Nita Wahyuni in preparation for a Hindu ritual at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, second right, sits in her classroom in Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, prepares for school at her home in Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Kadek Krisni prepares a headgear for her daughter to participate in Rejang Pucuk at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Kadek Krisni picks flower to prepare a headgear for her daughter for a Hindu ceremony at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, performs the Rehang Dewa, a sacred Balinese dance, at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, centre, performs the Rehang Dewa, a sacred Balinese dance, at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Kadek Krisni fixes an incense stick on the headgear of her daughter Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, before a Hindu ritual at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Kadek Krisni, left, walks with her daughter Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, to participate in a Hindu ceremony at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, prays as she perform a Hindu ritual at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

There are various forms of rejang performed during different occasions and rituals in Bali. Wahyuni and her friends have an important role during the festival. Rejang Dewa and Rejang Pucuk, performed on two separate days, are reserved only for girls who have not yet attained puberty.

“Being a rejang started when she lost her tooth until pre-puberty. We believe they are still pure to present dance to God during this time,” her father Nyoman Subrata says.

As traditional chief of Geriana Kauh village, Subrata says he is proud to see his daughter participating in this ritual. Subrata is committed to the responsibilities of maintaining religious traditions that have passed down through generations.

Balinese Hinduism brings together Hindu philosophy and local animist traditions with some Buddhist influence. It is a way of life, building a connection between the people, their heritage, and the divine.

A day later, Wahyuni’s mother Kadek Krisni has picked fresh flowers from their garden and prepared an elaborate headdress while her daughter was in school. Today is Rejang Pucuk day, one of the most sacred forms of Rejang. It was routine as usual in the morning. The latter half of the day will be spent in the temple. This is life in Bali.

Krisni says she participated in the same rituals as a child and is “happy there there is someone in the family continuing the ritual.”

There is apparent pride even in someone as young as Wahyuni in offering her service to the temple. Her friends are also part of the group and there is excitement as they share their experiences.

“I also learn how to apply makeup,” she says with a smile.

But despite the strong roots, there is also a fear for these traditions' place in the future. Subrata expresses concern that the younger generation is opting to leave the village for the city or overseas in search of work. He stresses the importance of being pragmatic and finding ways to maintain the Balinese traditional heritage without it being an impediment to the economic growth of the people.

“It is natural when they grow up and make their own choices, but I hope they don’t forget the place where they were born and their cultural traditions," he says.

Nyoman Subrata, traditional chief of Geriana Kauh village, thanks villagers for participating in Ngusaba Goreng at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

A Hindu priest in trance points keris, traditional dagger, on his chest during a Hindu ceremony at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, left, participates in Rejang Pucuk at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, second left, stands with her friends as they participate in Rejang Pucuk in at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni is dressed up to participate in Rejang Pucuk Hindu ritual ceremony at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni is dressed up to participate in Rejang Pucuk Hindu ritual ceremony at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, looks at her phone with her father Nyoman Subrata sitting beside her, as mother Kadek Krisni, right, and sister Intan Wahyuni, in blue, dresses up her cousin Rina Lestianti before the Rejang Pucuk Hindu rituals at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Intan Wahyuni applies makeup for her younger sister Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, before participating in Rejang Pucuk Hindu rituals at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Sari gives an offering during Ngusaba Goreng, a thanksgiving festival for a rich harvest, at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Nyoman Subrata, traditional chief of Geriana Kauh village, carries a rooster used in rituals for Ngusaba Goreng festival at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Kadek Krisni, left, tries on a headgear for size on her daughter Kadek Nita Wahyuni in preparation for a Hindu ritual at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, second right, sits in her classroom in Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, prepares for school at her home in Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Kadek Krisni prepares a headgear for her daughter to participate in Rejang Pucuk at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Kadek Krisni picks flower to prepare a headgear for her daughter for a Hindu ceremony at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, performs the Rehang Dewa, a sacred Balinese dance, at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, centre, performs the Rehang Dewa, a sacred Balinese dance, at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Kadek Krisni fixes an incense stick on the headgear of her daughter Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, before a Hindu ritual at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia on Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Kadek Krisni, left, walks with her daughter Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, to participate in a Hindu ceremony at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

Ketut Nita Wahyuni, 11, prays as she perform a Hindu ritual at Geriana Kauh village, Karangasem, Bali, Indonesia, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Firdia Lisnawati)

OUAGADOUGOU, Burkina Faso (AP) — Their loved ones were slaughtered by Islamic extremists or government-affiliated fighters. Their villages were attacked, their homes destroyed. Exhausted and traumatized, they fled in search of safety, food and shelter.

This is the reality for over 2.1 million displaced people across the West African nation of Burkina Faso, torn apart by years of extreme violence.

But unlike others displaced in the region, they are seen as a challenge to Burkina Faso's military junta that took power two years ago on the pledge of bringing stability. Their existence contradicts its official narrative: that security is improving and people are safely returning home.

Those who fled to Ouagadougou, the capital, which has been shielded from violence, find fear instead of respite. They are made into shadows, with many resorting to begging. Most of them are not entitled to support from authorities, and international aid organizations are not authorized to work with them.

The Associated Press reached out to several international aid groups, Western diplomats and the United Nations. None would speak on the record about the issue.

With no official displacement sites in Ouagadougou, no one knows how many people shelter in the capital or sleep on the streets. A rare acknowledgement of their existence by authorities noted 30,000 last year.

But aid groups say real numbers are much higher. And as violence increases, and people crowd displacement sites in the country's remote north and east, exposed to hunger and disease, more are expected to arrive in the capital.

One aid worker, speaking like others on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation, described the situation as “a ticking bomb.”

The AP interviewed four displaced people in Ouagadougou. All spoke at great risk. Three are with the Fulani ethnic group, which authorities accuse of being affiliated with Islamic insurgents. All three said they have faced discrimination in the capital, with trouble finding jobs and sending children to school.

For decades, the Fulani were neglected by the central government, and some did join miitants. As a result, Fulani civilians are often targeted both by the extremists — affiliated with al-Qaida or the Islamic State group — and by rival pro-government forces.

A 27-year-old Fulani cattle trader from Djibo, a city besieged by armed groups since 2022, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of repercussions from authorities, said government-affiliated forces indiscriminately treated all Fulani in the area as extremists.

“They started arresting people, bringing them to the city, beating them, undressing them. It was humiliating," he said. His uncle spent seven months in prison because he received aid from a charity run by extremists in part to spread their ideology.

He said he was arrested once in Djibo and beaten by the military, with injuries so extensive that he went to the hospital. He said soldiers told him only that they were “conducting a security operation.”

According to analysts, the junta's strategy of military escalation, including mass recruitment of civilians for poorly trained militia units, has exacerbated tensions between ethnic groups. Data gathered by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project show that militia attacks on civilians significantly increased since Capt. Ibrahim Traore took power.

The violence has radicalized some Fulanis, the cattle trader said.

“Every day, you prayed to live through the next 24 hours," he said. “This is not a life.”

He did not want to flee and leave his parents behind. But one day, his father woke him and said: “You have to leave, because if you stay, someone will just come and kill you.”

His father was later killed.

He left in a military convoy over a year ago. Life in Ouagadougou is “very difficult,” he said. He lives with extended family and relies on odd jobs to get by.

“There are mornings when I wake up and ask myself how will I get something to eat,” he said. “I used to live with dignity.”

His mother has joined him in the capital. They have not received support from the government.

A 28-year-old mother from the northwest, who also spoke on condition of anonymity, said at first the extremists came to her village and stole cattle. But last summer, they came to the market and killed several men, including her husband. Then they ordered women and children to leave.

She grabbed her children, and cooking pots, and fled. She walked for hours through the night until she reached her husband’s family home.

Ten days later, armed men were approaching. She strapped her 2-year-old daughter to her back, grabbed her 4-year-old son and left for the capital.

She said she has not received government support in Ouagadougou. She was promised a job as a cleaner but lost the offer once the employer found out she was Fulani.

She secured a place at a rare shelter for displaced women, run with Western-supplied funds by a local activist who tries to keep a low profile. She is learning how to sew and has enrolled her son in school.

“I miss my village,” she said. “But for the moment I have to wait until the violence is over.”

Her stay is precarious. The shelter is full, hosting 50 women and children. Usually, they are allowed to stay for one year. Time is running out.

The demand is enormous, the activist said, and there is less and less aid. Local authorities are wary of anyone working with displaced people.

“I don’t know for how much longer I can keep on going,” she said.

As much as 80% of Burkina Faso's territory is controlled by extremist groups and more civilians died from violence last year than in the years before, but in Ouagadougou, it is easy to forget that the government is battling an insurgency.

Busy open-air restaurants serve beer and the national dish of slowly roasted chicken. In recent months, the capital hosted a theater festival and an international arts and crafts fair. The authorities reinstated a cross-country cycling race, Tour de Faso, previously cancelled due to insecurity.

The military leadership has installed a system of de facto censorship, rights groups said, and those daring to speak up can be openly abducted, imprisoned or forcefully drafted into the army.

Burkina Faso used to be known for its vibrant intellectual life. Now, even friends are afraid to discuss politics.

“I feel like I am in prison,” said a local women’s rights activist. “Everyone distrusts each other. We fought for the freedom of speech, and now we lost everything.”

Burkina Faso's authorities did not respond to questions.

This story corrects the number of the displaced.

The Associated Press receives financial support for global health and development coverage in Africa from the Gates Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

FILE - People ride their scooters in the Gounghin district of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, Jan. 26, 2022. (AP Photo/Sophie Garcia, File)

FILE - A mural reading "Stay vigilant and mobilized" is seen in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, March 1, 2023. (AP Photo, File)

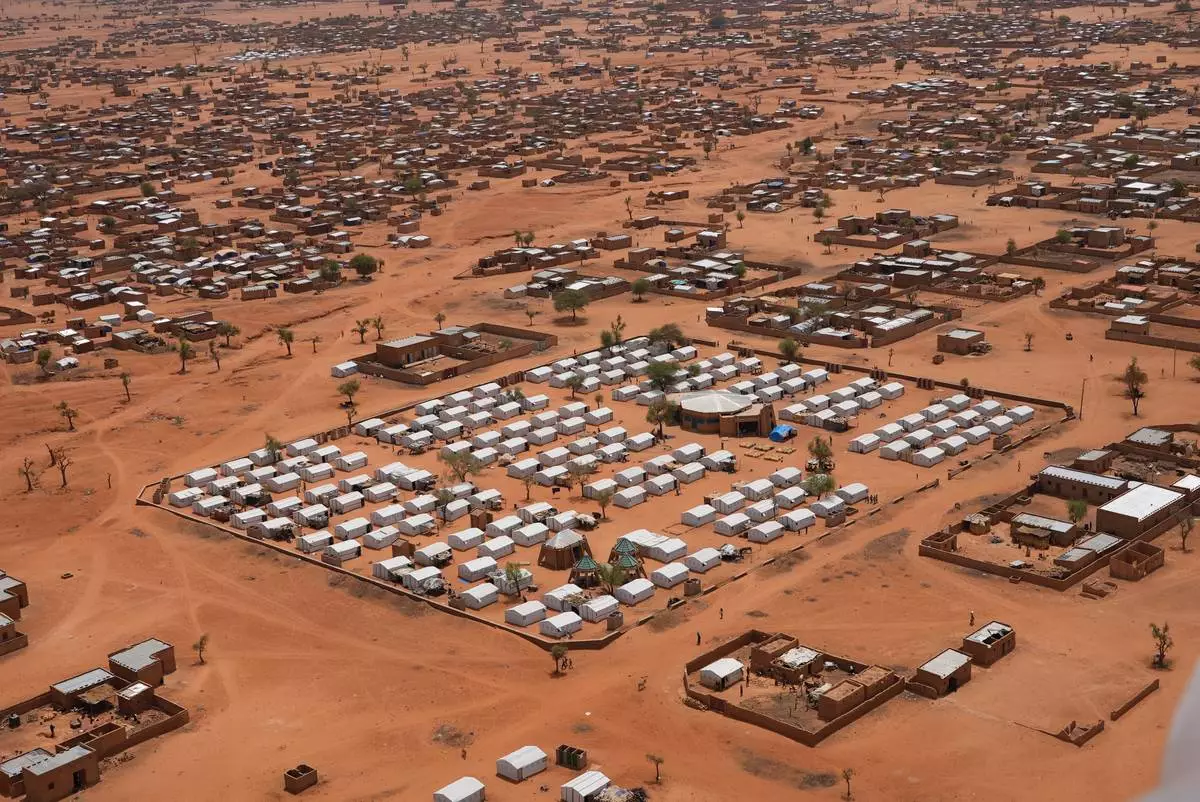

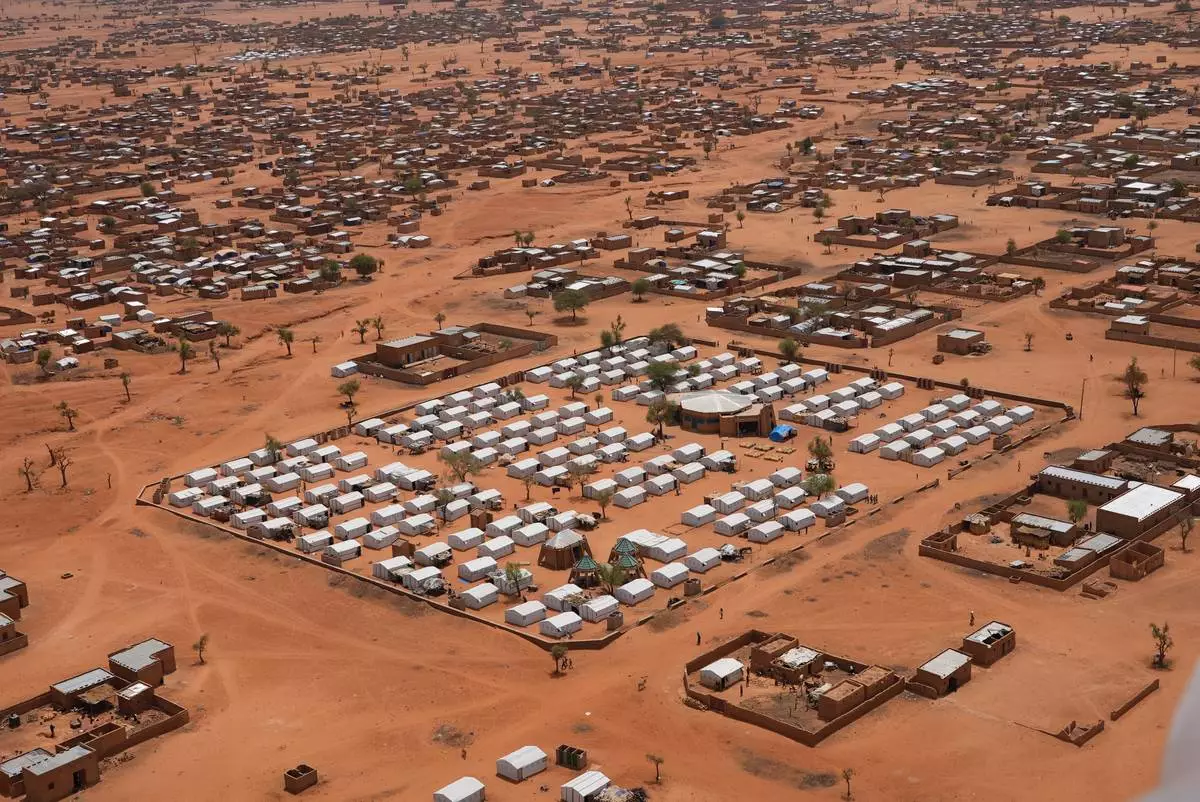

FILE - An aerial view shows a camp of internally displaced people in Djibo, Burkina Faso, May 26, 2022. (AP Photo/Sam Mednick, File)

FILE - Burkina Faso junta leader Ibrahim Traore participates in a ceremony in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, Oct. 15, 2022. (AP Photo/Kilaye Bationo, File)

FILE - Internally displaced people wait for aid in Djibo, Burkina Faso, May 26, 2022, when violence linked to al-Qaida and the Islamic State group began surging and spreading across the West African nation. (AP Photo/Sam Mednick, File)