SAN JUAN, Puerto Rico (AP) — Gangs in Haiti are recruiting children at unprecedented levels, with the number of minors targeted soaring by 70% in the past year, according to a report released Monday by UNICEF.

Currently, between 30% to 50% of all gang members in the violence-wracked country are children, according to the U.N.

“This is a very concerning trend,” said Geeta Narayan, UNICEF’s representative in Haiti.

The increase comes as poverty deepens and violence increases amid political instability, with gangs that control 85% of Port-au-Prince attacking once peaceful communities in a push to assume total control of the capital.

Young boys are often used as informers “because they’re invisible and not seen as a threat,” Narayan said in a phone interview from Haiti. Some are given weapons and forced to participate in attacks.

Girls, meanwhile, are forced to cook, clean and even used as so-called “wives” for gang members.

“They’re not doing this voluntarily,” Narayan said. “Even when they are armed with weapons, the child here is the victim.”

In a country where more than 60% of the population lives on less than $4 a day and hundreds of thousands of Haitians are starving or nearing starvation, recruiting children is often easy.

One minor who was in a gang said he was paid $33 every Saturday, while another said he was paid thousands of dollars in his first month in a gang operation, according to a U.N. Security Council report.

“Children and families are becoming increasingly desperate in some cases because of the extreme poverty,” Narayan said.

If children refuse to join a gang, gunmen often threaten them or their families or simply abduct them.

Gangs also prey on children who are separated from their families after they are deported from the Dominican Republic, which shares a border with Haiti on the island of Hispaniola.

“Those children are increasingly the ones targeted,” Narayan said.

Gangs aren’t the only threat as a vigilante movement that began last year to target suspected gang members gains momentum.

UNICEF said children “are often viewed with suspicion, and risk being branded as spies or even killed by vigilante movements. When they defect or refuse to join the violence, their lives and safety are immediately at risk.”

A video posted on social media last week after gangs attacked an area around an upscale community showed the body of a child lying next to an adult who also was slain. Police said that at least 28 suspected gang members were killed that day as residents armed with guns and machetes fought side-by-side with officers.

The gangs that recruit the most children are 5 Segond, Brooklyn, Kraze Barye, Grand Ravine and Terre Noire, according to the U.N. Security Council report.

Usually, new recruits are ordered to buy food and are given money to “buy friends” as gangs observe them. Then, they participate in confrontations and are promoted if they kill someone, for example. After two or three years in the gang, the recruit becomes part of the entourage if they prove they weren’t a spy, according to the report.

Recruitment is surging as many schools remain closed and children become increasingly vulnerable, with gang violence leaving more than 700,000 people homeless in recent years, including an estimated 365,000 minors. Many of them live in makeshift shelters where they’re preyed upon by gangs and face physical and sexual violence.

“Criminal groups in Haiti are subjecting girls and women to horrific sexual abuse,” stated a report published Monday by Human Rights Watch.

The report quoted a 14-year-old girl from the capital who said she was abducted and raped multiple times by different men for five days in a house with six other girls who also were raped and beaten.

Human Rights Watch noted that while fighting between armed groups has decreased this year, attacks on Haitians, police and critical infrastructure has increased.

“Criminal groups have often used sexual violence to instill fear in rival territories,” it said.

Gangs are targeting children as young as eight years old, and the longer they spend with an armed group, the harder it is to rescue them and reintegrate them into society, according to experts.

Violence is rewarded and encouraged, which Narayan said is extremely harmful to a child’s psychosocial development.

Children quit gangs in several ways: some leave willingly, others escape and sometimes nonprofits will find them and take them to centers where they receive medical care if needed as well as psychological help and other aid.

“There is a transition period,” Narayan said. ”It’s not all rosy. It does take time on all sides.”

An asthmatic girl rests as she takes refuge in a private school serving as a shelter for residents fleeing gang violence in the Nazon neighborhood, in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Odelyn Joseph)

Residents flee their homes to escape gang violence in the Nazon neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Odelyn Joseph)

Residents flee their homes to escape gang violence in the Nazon neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024. (AP Photo/Odelyn Joseph)

EAST LANSING, Mich. (AP) — The sight was a common one for Andrew Kolpacki. For many a Sunday, he would watch NFL games on TV and see quarterbacks putting their hands on their helmets, desperately trying to hear the play call from the sideline or booth as tens of thousands of fans screamed at the tops of their lungs.

When the NCAA’s playing rules oversight committee this past spring approved the use of coach-to-player helmet communications in games for the 2024 season, Kolpacki, Michigan State’s head football equipment manager, knew the Spartans’ QBs and linebackers were going to have a problem.

“There had to be some sort of solution,” he said.

As it turns out, there was. And it was right across the street.

Kolpacki reached out to Tamara Reid Bush, a mechanical engineering professor who not only heads the school’s Biomechanical Design Research Laboratory but also is a football season ticket-holder.

Kolpacki “showed me some photos and said that other teams had just put duct tape inside the (earhole), and he asked me, ‘Do you think we can do anything better than duct tape,?” Bush said. “And I said, ‘Oh, absolutely.’”

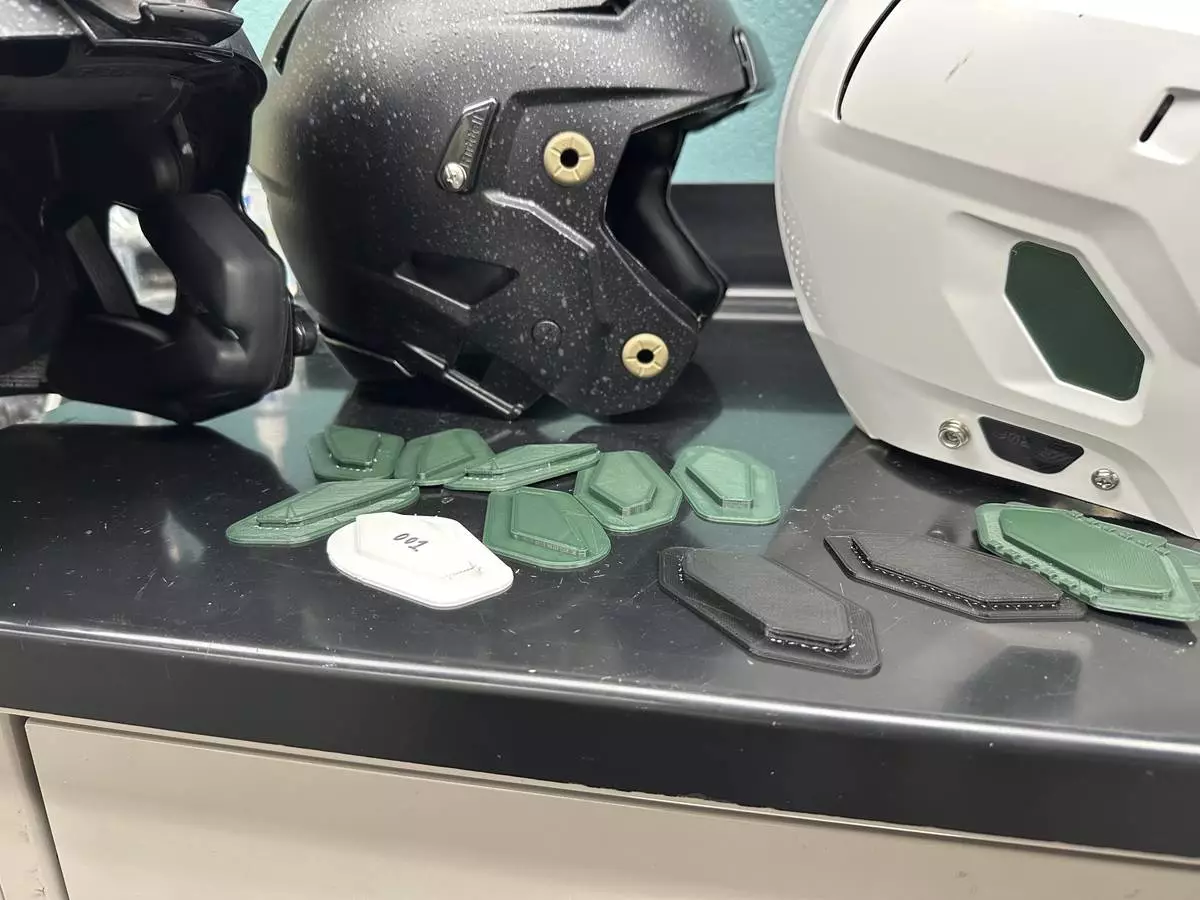

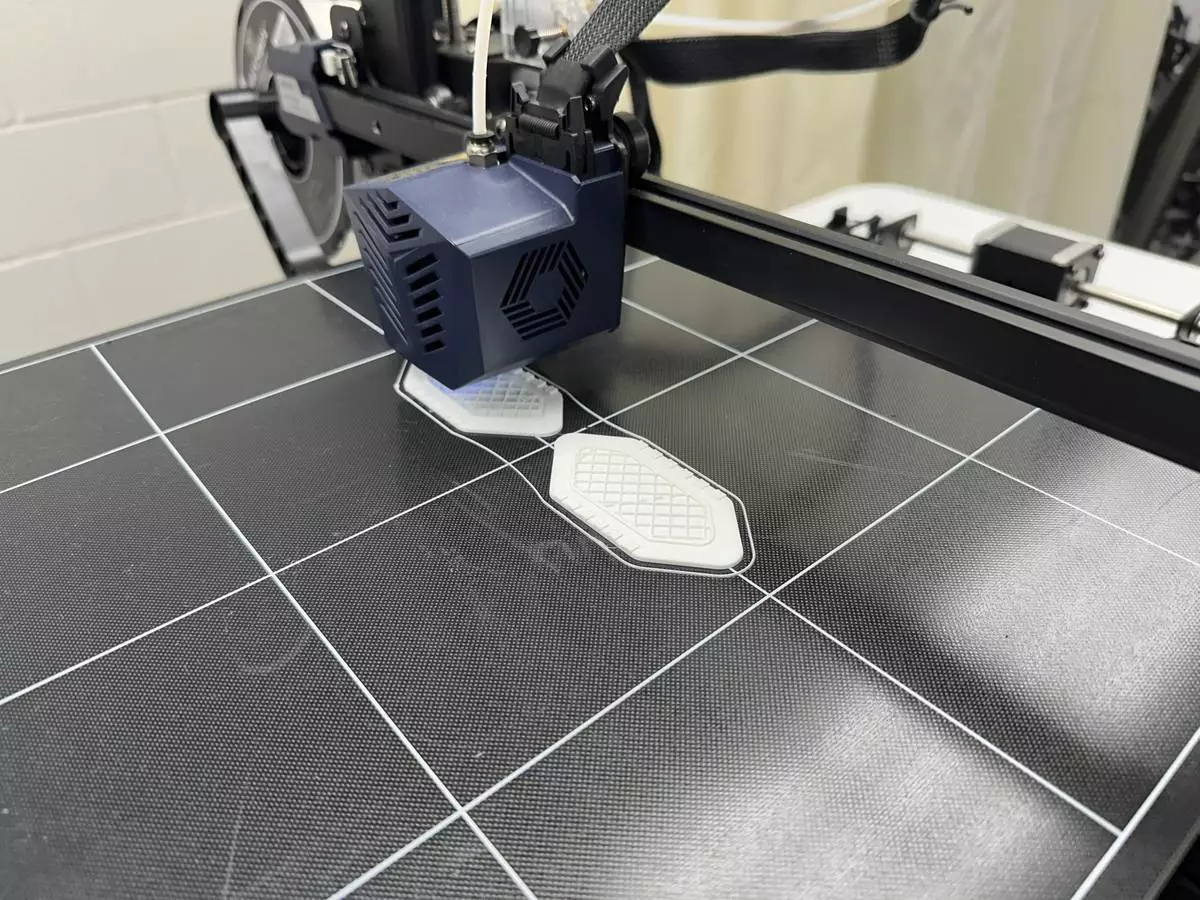

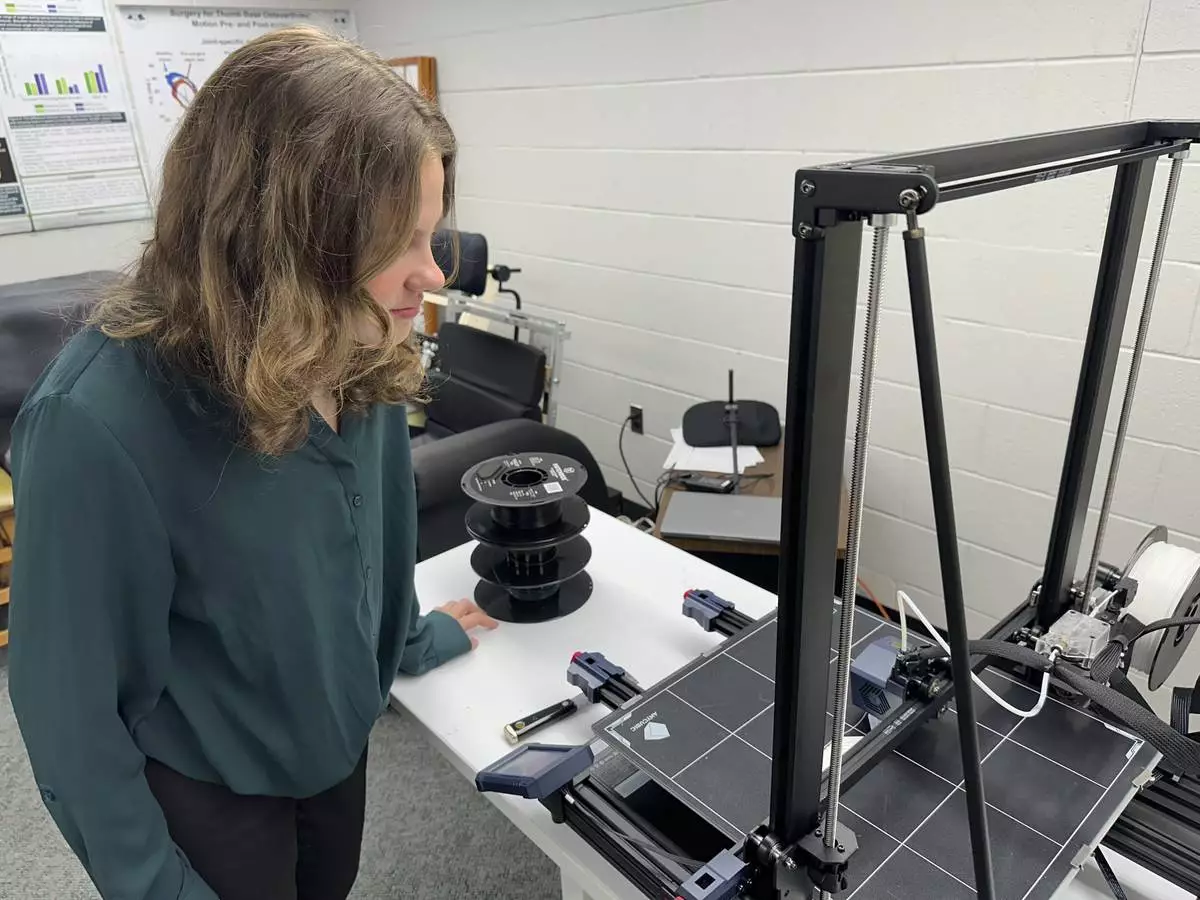

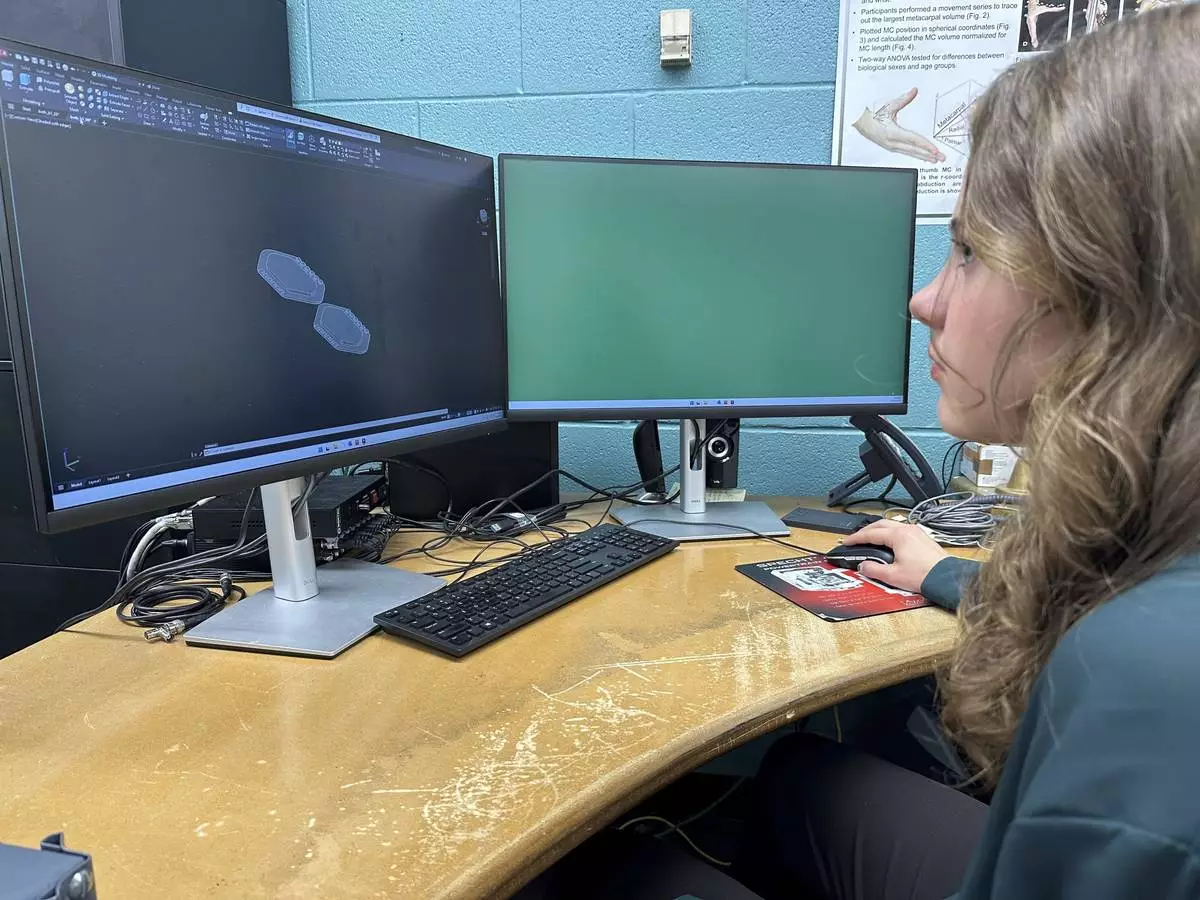

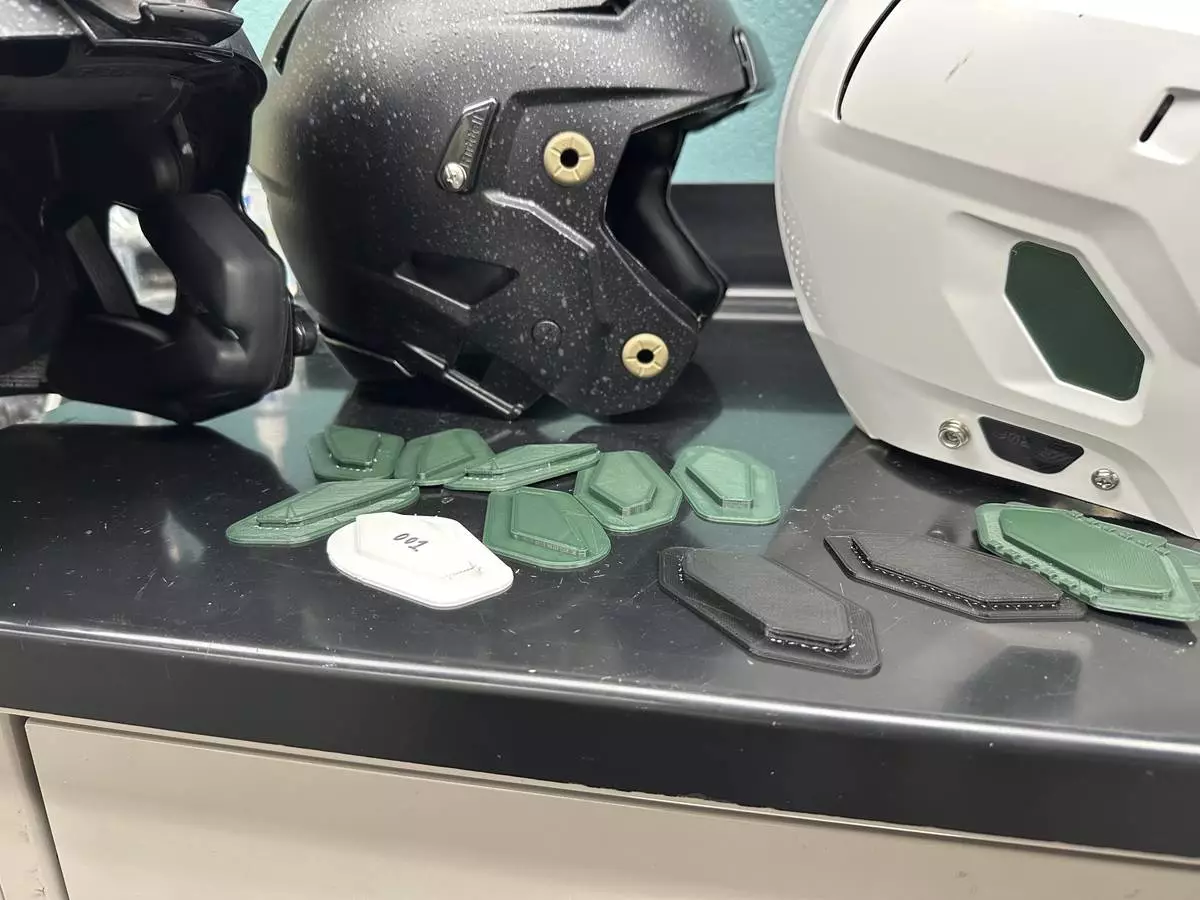

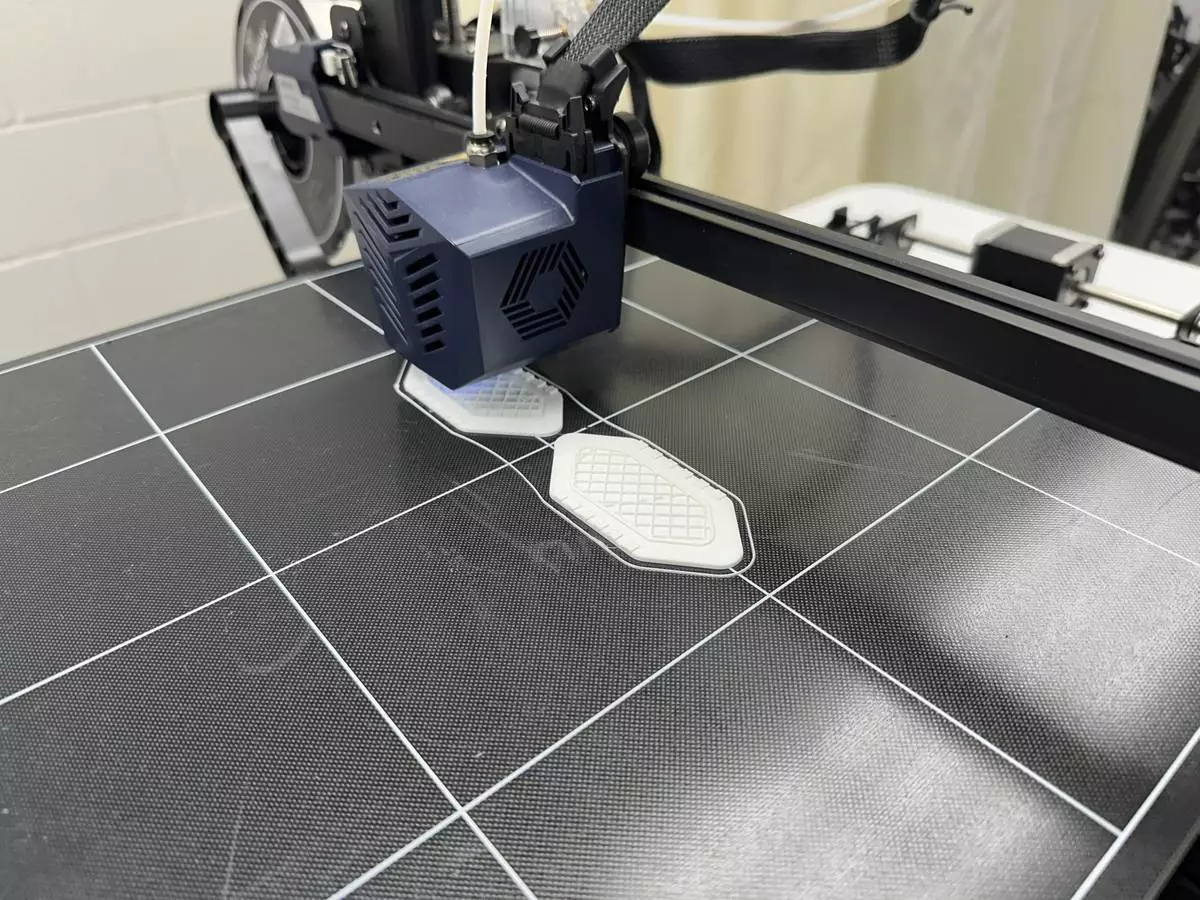

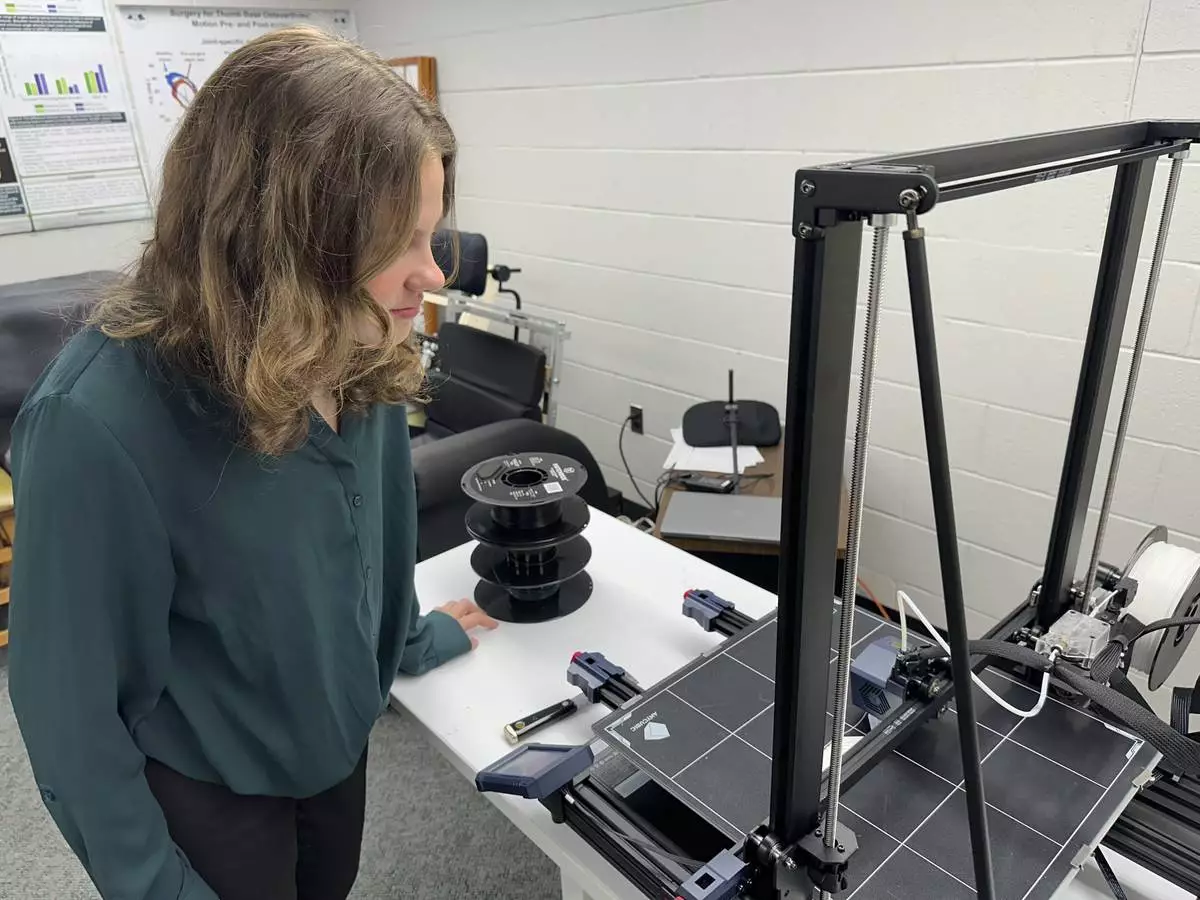

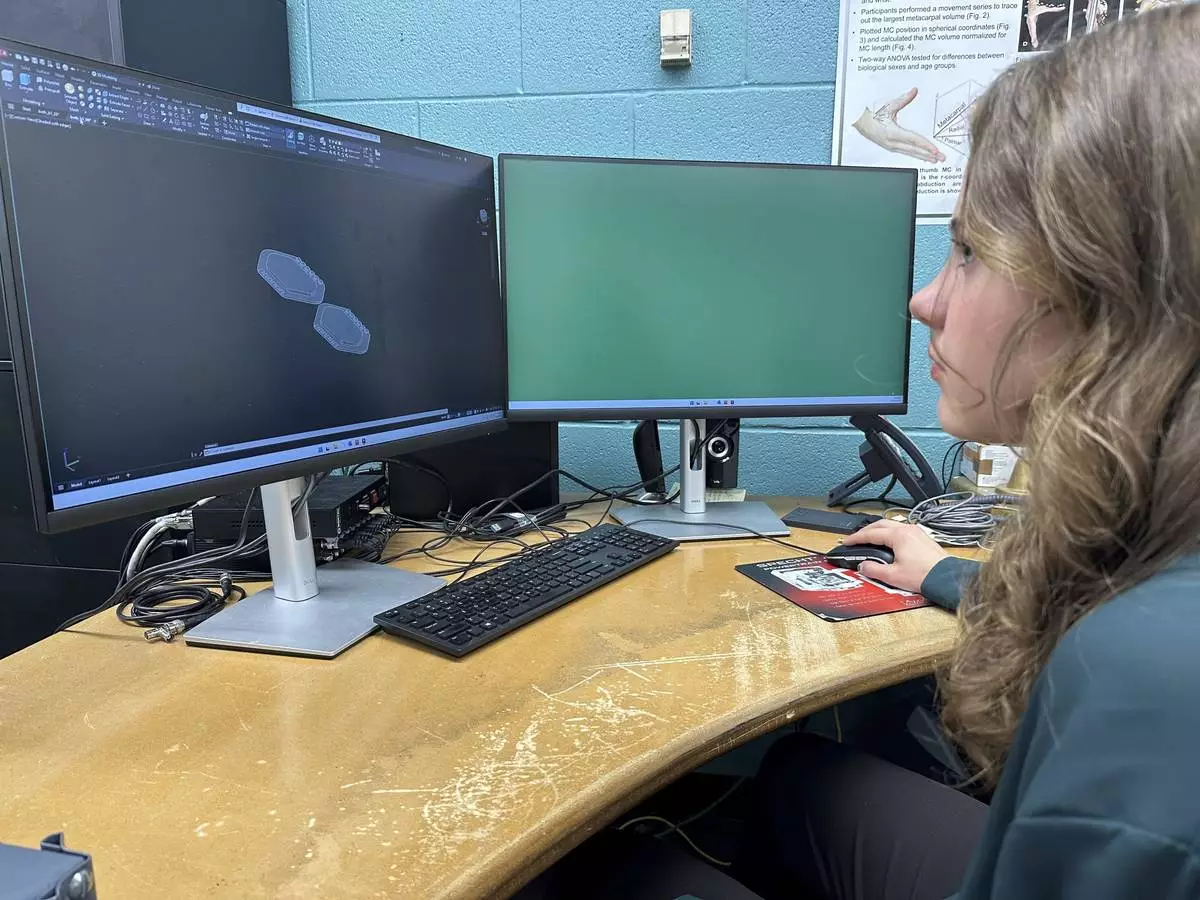

Bush and Rylie DuBois, a sophomore biosystems engineering major and undergraduate research assistant at the lab, set out to produce earhole inserts made from polylactic acid, a bio-based plastic, using a 3D printer. Part of the challenge was accounting for the earhole sizes and shapes that vary depending on helmet style.

Once the season got underway with a Friday night home game against Florida Atlantic on Aug. 30, the helmets of starting quarterback Aidan Chiles and linebacker Jordan Turner were outfitted with the inserts, which helped mitigate crowd noise.

DuBois attended the game, sitting in the student section.

“I felt such a strong sense of accomplishment and pride,” DuBois said. “And I told all my friends around me about how I designed what they were wearing on the field.”

All told, Bush and DuBois have produced around 180 sets of the inserts, a number that grew in part due to the variety of helmet designs and colors that are available to be worn by Spartan players any given Saturday. Plus, the engineering folks have been fine-tuning their design throughout the season.

Dozens of Bowl Subdivision programs are doing something similar. In many cases, they’re getting 3D-printed earhole covers from XO Armor Technologies, which provides on-site, on-demand 3D printing of athletic wearables.

The Auburn, Alabama-based company has donated its version of the earhole covers to the equipment managers of programs ranging from Georgia and Clemson to Boise State and Arizona State in the hope the schools would consider doing business with XO Armor in the future, said Jeff Klosterman, vice president of business development.

XO Armor first was approached by the Houston Texans at the end of last season about creating something to assist quarterback C.J. Stroud in better hearing play calls delivered to his helmet during road games. XO Armor worked on a solution and had completed one when it received another inquiry: Ohio State, which had heard Michigan State was moving forward with helmet inserts, wondered if XO Armor had anything in the works.

“We kind of just did this as a one-off favor to the Texans and honestly didn’t forecast it becoming our viral moment in college football,” Klosterman said. “We’ve now got about 60 teams across college football and the NFL wearing our sound-deadening earhole covers every weekend.”

The rules state that only one player for each team is permitted to be in communication with coaches while on the field. For the Spartans, it’s typically Chiles on offense and Turner on defense. Turner prefers to have an insert in both earholes, but Chiles has asked that the insert be used in only one on his helmet.

Chiles “likes to be able to feel like he has some sort of outward exposure,” Kolpacki said.

Exposure is something the sophomore signal-caller from Long Beach, California, had in away games against Michigan and Oregon this season. Michigan Stadium welcomed 110,000-plus fans for the Oct. 26 matchup between the in-state rivals. And while just under 60,000 packed Autzen Stadium in Eugene, Oregon, for the Ducks' 31-10 win over Michigan State three weeks earlier, it was plenty loud. “The Big Ten has some pretty impressive venues,” Kolpacki said.

“It can be just deafening,” he said. “That's what those fans are there for is to create havoc and make it difficult for coaches to get a play call off.”

Something that is a bit easier to handle thanks to Bush and her team. She called the inserts a “win-win-win" for everyone.

“It’s exciting for me to work with athletics and the football team," she said. "I think it’s really exciting for our students as well to take what they’ve learned and develop and design something and see it being used and executed.”

Get alerts on the latest AP Top 25 poll throughout the season. Sign up here. AP college football: https://apnews.com/hub/college-football and https://apnews.com/hub/ap-top-25-college-football-poll

A 3D printer creates helmet inserts at Michigan State University's Biomechanical Design Research Laboratory, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in East Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Mike Householder)

A 3D printer creates helmet inserts at Michigan State University's Biomechanical Design Research Laboratory, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in East Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Mike Householder)

Rylie DuBois, a sophomore biosystems engineering major at Michigan State University, watches as a 3D printer creates helmet inserts at the school's Biomechanical Design Research Laboratory, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in East Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Mike Householder)

Rylie DuBois, a sophomore biosystems engineering major at Michigan State University, uses a computer-aided design program at the school's Biomechanical Design Research Laboratory, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in East Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Mike Householder)

Rylie DuBois, a sophomore biosystems engineering major at Michigan State University, uses a computer-aided design program at the school's Biomechanical Design Research Laboratory, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in East Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Mike Householder)

Andrew Kolpacki, Michigan State University's head football equipment manager, holds three helmet inserts created by a professor at the school's College of Engineering, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in East Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Mike Householder)

Andrew Kolpacki, Michigan State University's head football equipment manager, examines part of a coach-to-player communication system inside the school's football complex, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in East Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Mike Householder)

Andrew Kolpacki, Michigan State University's head football equipment manager, surveys players' helmets located on a table inside the school's football complex, Monday, Nov. 18, 2024, in East Lansing, Mich. (AP Photo/Mike Householder)