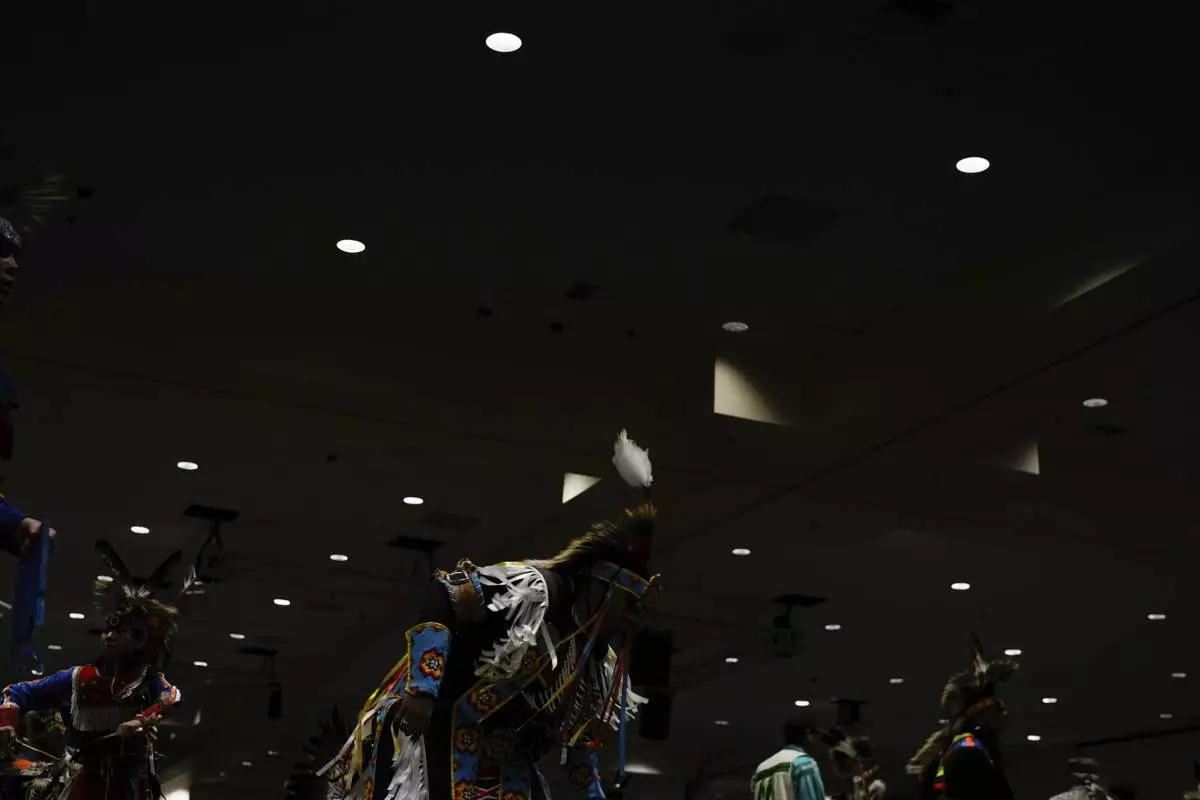

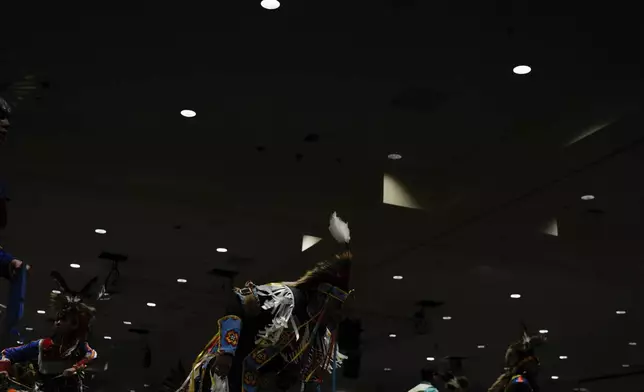

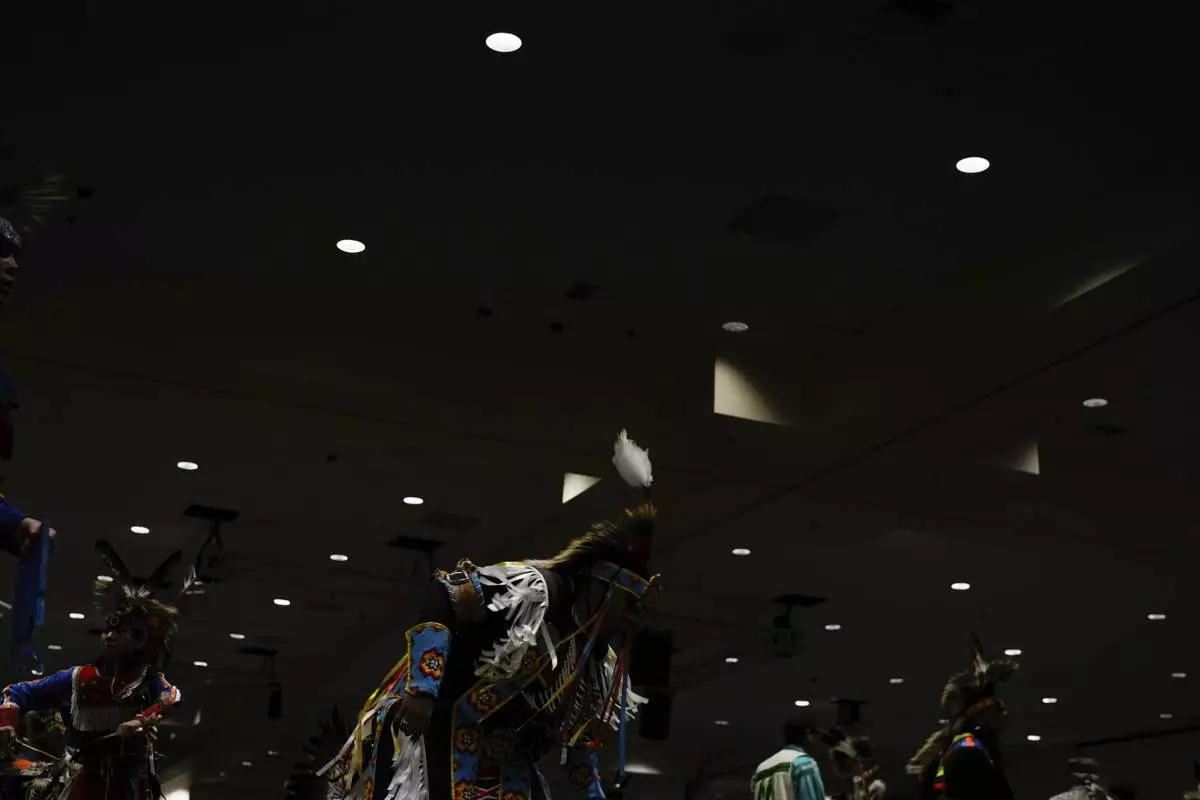

LINCOLN CITY, Ore. (AP) — Drumming made the floor vibrate and singing filled the conference room of the Chinook Winds Casino Resort in Lincoln City, on the Oregon coast, as hundreds in tribal regalia danced in a circle.

For the last 47 years, the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians have held an annual powwow to celebrate regaining federal recognition. This month’s event, however, was especially significant: It came just two weeks after a federal court lifted restrictions on the tribe's rights to hunt, fish and gather — restrictions tribal leaders had opposed for decades.

Click to Gallery

Members of the Warrior Society drum group, clockwise from bottom left, Taylor Hawk, Jimmy Williams, J.J. Jackson, Lawney Havranek, George Clements, Henry Rondeau, Plummie Wright, and Ron Butler, perform during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians member Ramona Hudson, of Aumsville, Ore., right, looks up as her cousin Aurora Chulik-Ruff, 12, holds her five-month-old brother Bear Chulik-Moore, as they walk during a dance dedicated to missing and murdered indigenous women during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Members of the Warrior Society drum group, clockwise from bottom left, Taylor Hawk, Jimmy Williams, J.J. Jackson, Lawney Havranek, George Clements, Henry Rondeau, Plummie Wright, and Ron Butler, perform during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Feathers are displayed on regalia during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Stuart Whitehead dances during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

People gather around Chet Clark, in the white hat at center, as he plays an honor song for the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. Chet, of the drum group Johonaaii, wrote the song in 2007 and sang it for the first time during the tribe's 30th restoration powwow. It has been sung during every restoration powwow since then. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

People hold hands during a dance at a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

People dance in a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

People clap as an image of land recently purchased by the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians is displayed on a screen during a lunch for tribal members and guests before a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

People dance during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

The Chinook Winds Casino Resort is seen on Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Tribal Chairman of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians Delores Pigsley speaks during an interview with The Associated Press at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Sun-taa-chu Butler, right, hugs a friend as they get ready for a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

A dream catcher is seen on an eagle staff during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

An image of land recently purchased by the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians is displayed on a screen during a lunch for tribal members and guests before a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians member Ramona Hudson, of Aumsville, Ore., right, looks up as her cousin Aurora Chulik-Ruff, 12, holds her five-month-old brother Bear Chulik-Moore, as they walk during a dance dedicated to missing and murdered indigenous women during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Taylor Hawk, a member of the Warrior Society drum group, touches the drum after playing during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Tiffany Stuart, at right in white, holds hands with her daughter Kwestaani Chuski Stuart, bottom right, as they participate in a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Kimberly Jurado holds her daughter, Delia Rubi Jurado, as they walk during a dance at a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

People dance during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

“We're back to the way we were before,” Siletz Chairman Delores Pigsley said. “It feels really good.”

The Siletz is a confederation of over two dozen bands and tribes whose traditional homelands spanned western Oregon, as well as parts of northern California and southwestern Washington state. The federal government in the 1850s forced them onto a reservation on the Oregon coast, where they were confederated together as a single, federally recognized tribe despite their different backgrounds and languages.

In the 1950s and ‘60s, Congress revoked recognition of over 100 tribes, including the Siletz, under a policy known as “termination.” Affected tribes lost millions of acres of land as well as federal funding and services.

“The goal was to try and assimilate Native people, get them moved into cities,” said Matthew Campbell, deputy director of the Native American Rights Fund. “But also I think there was certainly a financial aspect to it. I think the United States was trying to see how it could limit its costs in terms of providing for tribal nations.”

Losing their lands and self-governance was painful, and the tribes fought for decades to regain federal recognition. In 1977, the Siletz became the second tribe to succeed, following the restoration of the Menominee Tribe in Wisconsin in 1973.

But to get a fraction of its land back — roughly 3,600 acres (1,457 hectares) of the 1.1-million-acre (445,000-hectare) reservation established for the tribe in 1855 — the Siletz tribe had to agree to a federal court order that restricted their hunting, fishing and gathering rights. It was only one of two tribes in the country, along with Oregon’s Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde, compelled to do so to regain tribal land.

The settlement limited where tribal members could fish, hunt and gather for ceremonial and subsistence purposes, and it imposed caps on how many salmon, elk and deer could be harvested in a year. It was devastating, tribal chair Pigsley recalled: The tribe was forced to buy salmon for ceremonies because it couldn’t provide for itself, and people were arrested for hunting and fishing violations.

“Giving up those rights was a terrible thing,” Pigsley, who has led the tribe for 36 years, told The Associated Press earlier this year. “It was unfair at the time, and we’ve lived with it all these years.”

Decades later, Oregon and the U.S. came to recognize that the agreement subjecting the tribe to state hunting and fishing rules was biased, and they agreed to join the tribe in recommending to the court that the restrictions be lifted.

“The Governor of Oregon and Oregon’s congressional representatives have since acknowledged that the 1980 Agreement and Consent Decree were a product of their times and represented a biased and distorted position on tribal sovereignty, tribal traditions, and the Siletz Tribe’s ability and authority to manage and sustain wildlife populations it traditionally used for tribal ceremonial and subsistence purposes,” attorneys for the U.S., state and tribe wrote in a joint court filing.

Late last month, the tribe finally succeeded in having the court order vacated by a federal judge. And a separate agreement with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife has given the tribe a greater role in regulating tribal hunting and fishing.

As Pigsley reflected on those who passed away before seeing the tribe regain its rights, she expressed hope about the next generation carrying on essential traditions.

“There’s a lot of youth out there that are learning tribal ways and culture,” she said. “It’s important today because we are trying to raise healthy families, meaning we need to get back to our natural foods.”

Among those celebrating and praying at the powwow was Tiffany Stuart, donning a basket cap her ancestors were known for weaving, and her 3-year-old daughter Kwestaani Chuski, whose name means “six butterflies” in the regional Athabaskan language from southwestern Oregon and northwestern California.

Given the restoration of rights, Stuart said, it was “very powerful for my kids to dance.”

“You dance for the people that can’t dance anymore,” she said.

Members of the Warrior Society drum group, clockwise from bottom left, Taylor Hawk, Jimmy Williams, J.J. Jackson, Lawney Havranek, George Clements, Henry Rondeau, Plummie Wright, and Ron Butler, perform during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Feathers are displayed on regalia during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Stuart Whitehead dances during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

People gather around Chet Clark, in the white hat at center, as he plays an honor song for the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. Chet, of the drum group Johonaaii, wrote the song in 2007 and sang it for the first time during the tribe's 30th restoration powwow. It has been sung during every restoration powwow since then. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

People hold hands during a dance at a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

People dance in a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

People clap as an image of land recently purchased by the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians is displayed on a screen during a lunch for tribal members and guests before a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

People dance during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

The Chinook Winds Casino Resort is seen on Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Tribal Chairman of the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians Delores Pigsley speaks during an interview with The Associated Press at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Sun-taa-chu Butler, right, hugs a friend as they get ready for a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

A dream catcher is seen on an eagle staff during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

An image of land recently purchased by the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians is displayed on a screen during a lunch for tribal members and guests before a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians member Ramona Hudson, of Aumsville, Ore., right, looks up as her cousin Aurora Chulik-Ruff, 12, holds her five-month-old brother Bear Chulik-Moore, as they walk during a dance dedicated to missing and murdered indigenous women during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Taylor Hawk, a member of the Warrior Society drum group, touches the drum after playing during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Tiffany Stuart, at right in white, holds hands with her daughter Kwestaani Chuski Stuart, bottom right, as they participate in a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

Kimberly Jurado holds her daughter, Delia Rubi Jurado, as they walk during a dance at a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

People dance during a powwow at Chinook Winds Casino Resort, Saturday, Nov. 16, 2024, in Lincoln City, Ore. (AP Photo/Jenny Kane)

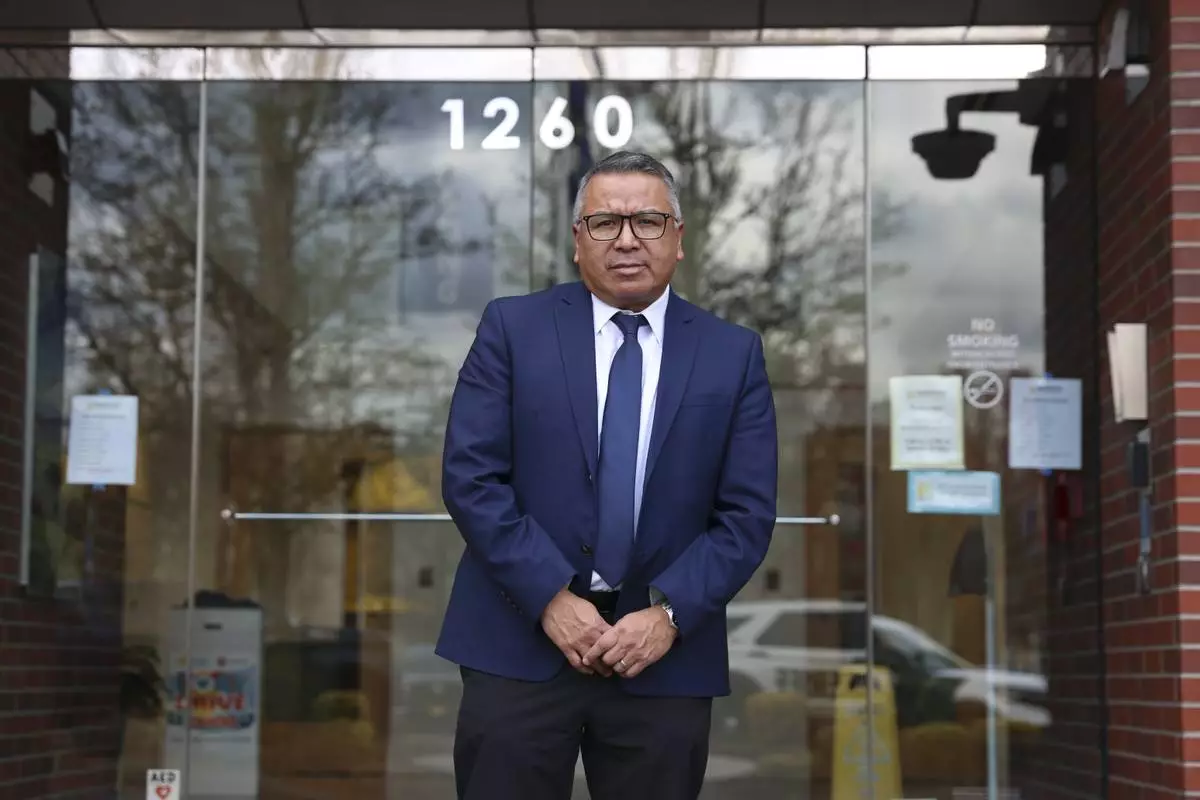

Last time Donald Trump was president, rumors of immigration raids terrorized the Oregon community where Gustavo Balderas was the school superintendent.

Word spread that immigration agents were going to try to enter schools. There was no truth to it, but school staff members had to find students who were avoiding school and coax them back to class.

“People just started ducking and hiding,” Balderas said.

Educators around the country are bracing for upheaval, whether or not the president-elect follows through on his pledge to deport millions of immigrants who are in the country illegally. Even if he only talks about it, children of immigrants will suffer, educators and legal observers said.

If “you constantly threaten people with the possibility of mass deportation, it really inhibits peoples’ ability to function in society and for their kids to get an education,” said Hiroshi Motomura, a professor at UCLA School of Law.

That fear already has started for many.

“The kids are still coming to school, but they’re scared,” said Almudena Abeyta, superintendent of Chelsea Public Schools, a Boston suburb that’s long been a first stop for Central American immigrants coming to Massachusetts. Now Haitians are making the city home and sending their kids to school there.

“They’re asking: ‘Are we going to be deported?’” said Abeyta.

Many parents in her district grew up in countries where the federal government ran schools and may think it’s the same here. The day after the election, Abeyta sent a letter home assuring parents their children are welcome and safe, no matter who is president.

Immigration officials have avoided arresting parents or students at schools. Since 2011, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement has operated under a policy that immigration agents should not arrest or conduct other enforcement actions near “sensitive locations,” including schools, hospitals and places of worship. Doing so might curb access to essential services, U.S. Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas wrote in a 2021 policy update.

The Heritage Foundation's policy roadmap for Trump’s second term, Project 2025, calls for rescinding the guidance on “sensitive places.” Trump tried to distance himself from the proposals during the campaign, but he has nominated many who worked on the plan for his new administration, including Tom Homan for “border czar.”

If immigration agents were to arrest a parent dropping off children at school, it could set off mass panic, said Angelica Salas, executive director of the Coalition for Humane Immigrant Rights in Los Angeles.

“If something happens at one school, it spreads like wildfire and kids stop coming to school,” she said.

Balderas, now the superintendent in Beaverton, a different Portland suburb, told the school committee there this month it was time to prepare for a more determined Trump administration. In case schools are targeted, Beaverton will train staff not to allow immigration agents inside.

“All bets are off with Trump,” said Balderas, who is also president of ASSA, The School Superintendents Association. “If something happens, I feel like it will happen a lot quicker than last time.”

Many school officials are reluctant to talk about their plans or concerns, some out of fear of drawing attention to their immigrant students. One school administrator serving many children of Mexican and Central American immigrants in the Midwest said their school has invited immigration attorneys to help parents formalize any plans for their children’s care in case they are deported. The administrator spoke on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak to the media.

Speaking up on behalf of immigrant families also can put superintendents at odds with school board members.

“This is a very delicate issue,” said Viridiana Carrizales, chief executive officer of ImmSchools, a nonprofit that trains schools on supporting immigrant students.

She’s received 30 requests for help since the election, including two from Texas superintendents who don’t think their conservative school boards would approve of publicly affirming immigrant students’ right to attend school or district plans to turn away immigration agents.

More than two dozen superintendents and district communications representatives contacted by The Associated Press either ignored or declined requests for comment.

“This is so speculative that we would prefer not to comment on the topic,” wrote Scott Pribble, a spokesperson for Denver Public Schools.

The city of Denver has helped more than 40,000 migrants in the last two years with shelter or a bus ticket elsewhere. It’s also next door to Aurora, one of two cities where Trump has said he would start his mass deportations.

When pressed further, Pribble responded, “Denver Public Schools is monitoring the situation while we continue to serve, support, and protect all of our students as we always have.”

Like a number of big-city districts, Denver’s school board during the first Trump administration passed a resolution promising to protect its students from immigration authorities pursuing them or their information. According to the 2017 resolution, Denver will not “grant access to our students” unless federal agents can provide a valid search warrant.

The rationale has been that students cannot learn if they fear immigration agents will take them or their parents away while they’re on campus. School districts also say these policies reaffirm their students’ constitutional right to a free, public education, regardless of immigration status.

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

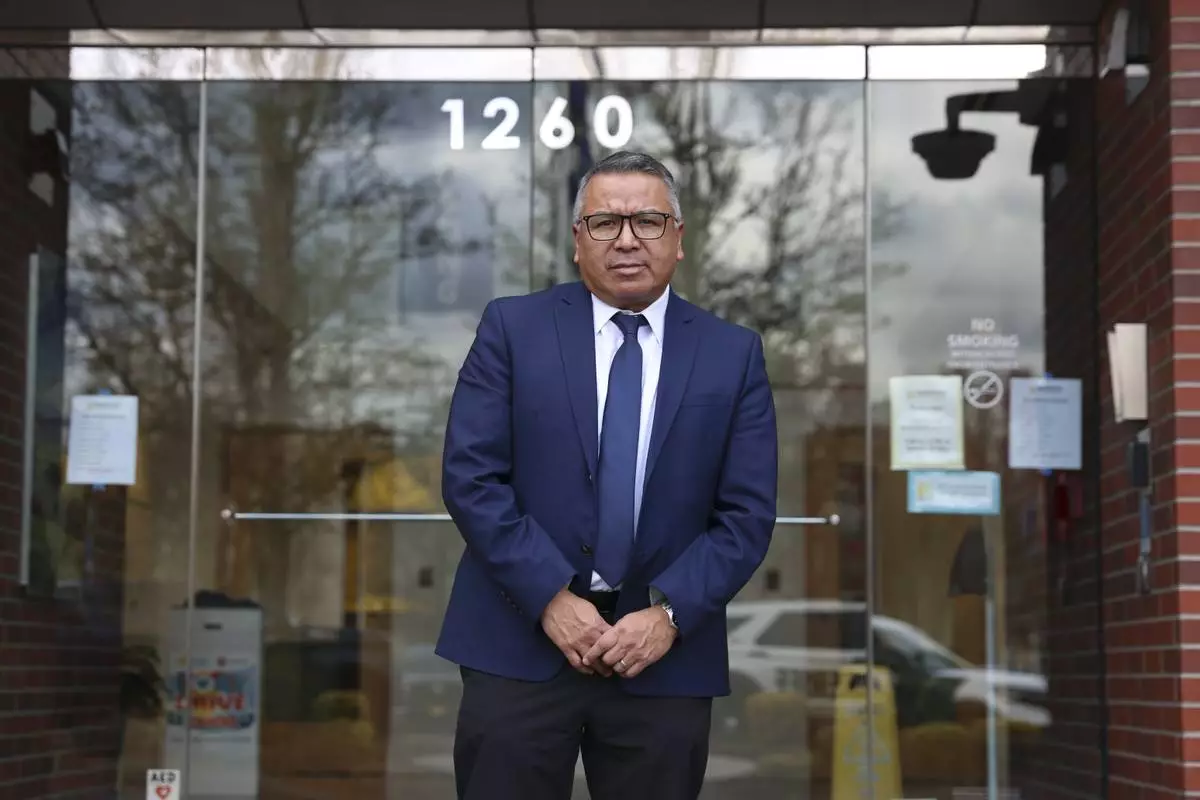

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, stands for a photo in the lobby of the district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, works in his office at the district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, works in his office at the district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, stands for a photo outside of the Beaverton school district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, stands for a photo outside of the Beaverton school district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

Gustavo Balderas, superintendent of Beaverton School District, stands for a photo outside of the Beaverton school district administrative office in Beaverton, Ore., Monday, Nov. 25, 2024. (AP Photo/Amanda Loman)

FILE - Jefferson County Public Schools buses make their way through the Detrick Bus Compound on the first day of school, Aug. 9, 2023, in Louisville, Ky. (Jeff Faughender/Courier Journal via AP, File)

FILE - An American flag hangs in a classroom as students work on laptops in Newlon Elementary School, Aug. 25, 2020, in Denver. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski, File)