DANIA BEACH, Florida (AP) — As immigration remains a hotly contested priority for the Trump administration after playing a decisive role in the deeply polarized election, the Border Patrol agents tasked with enforcing many of its laws are wrestling with growing challenges on and off the job.

More are training to become chaplains to help their peers as they tackle security threats, including the powerful cartels that control much of the border dynamic, and witness growing suffering among migrants — all while policies in Washington keep shifting and public outrage targets them from all sides.

“The hardest thing is, people … don’t know what we do, and we’ve been called terrible names,” said Brandon Fredrick, a Buffalo, New York-based agent some of whose family members have resorted to name-calling.

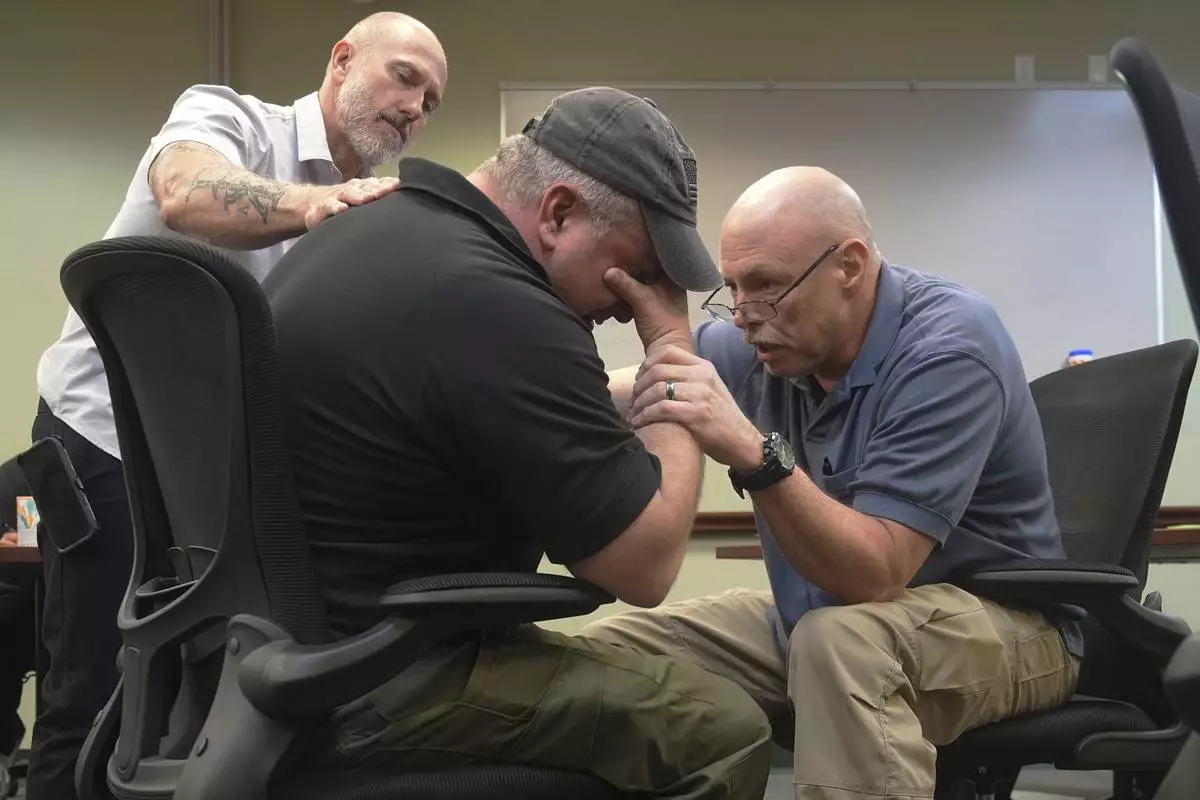

Earlier this month, he served as a training academy instructor for Border Patrol chaplains, whose numbers have almost doubled in the last four years. It's an effort to help agents motivated by the desire to keep the U.S. borders safe cope with mounting distress before it leads to family dysfunction, addiction, even suicide.

During the latest academy, held at a Border Patrol station near Miami, Fredrick evaluated pairs of chaplains-in-training as they role-played checking on a fellow agent who hadn’t reported for work.

They discovered he’d been drowning in alcohol his angst at being deployed away from his family for the holidays at one of the border’s hotspots. The training scenario was achingly real for the South Florida-based agent role-playing the distressed one — he had struggled when relocated for 18 months to Del Rio, Texas, away from his two children — and also for Fredrick, who overcame alcoholism before becoming a chaplain.

Interacting with chaplains can reduce the agents' reluctance to express their emotional trials, Fredrick said.

“My mission every day is that there’s not a young agent Fredrick suffering alone,” he added. Fredrick, a Catholic, has been an agent for more than 15 years and worked tragic cases like a smuggling attempt where an Indian family froze to death at the Canada-U.S. border.

Unlike the police or military, which recruits faith leaders for help with everything from suicide prevention to dealing with the unrest after George Floyd’s murder, the Border Patrol trains mostly lay agents endorsed by their faith denominations to become chaplains.

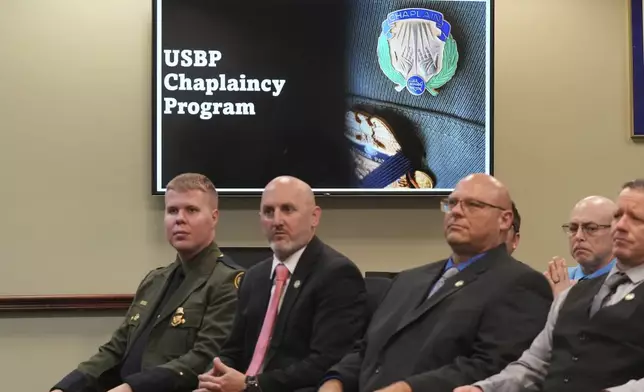

After graduating, they join about 240 other chaplains and resume their regular jobs — but they’re constantly on call to provide largely confidential care for their 20,000 fellow agents’ well-being.

While most chaplains are Christian, Muslim and Jewish agents also have been trained recently. The chaplains don’t offer faith-specific worship and only bring up religion if the person they’re helping does first.

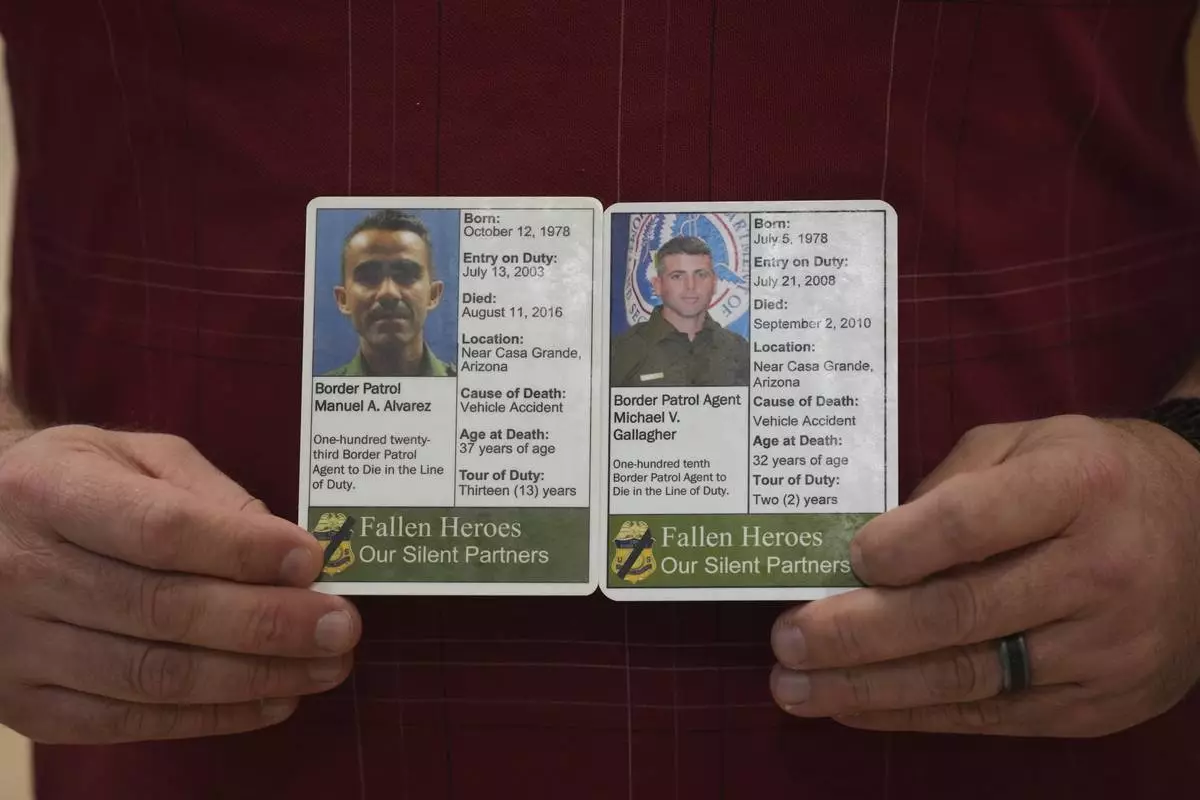

“I’m not there to convert or proselytize,” said academy instructor Jason Wilhite, an agent in Casa Grande, Arizona, and a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. A chaplain since 2015, he was previously involved in the agency's nonreligious, mental health-focused peer support program after a fellow agent died in a car accident.

Agent Jesus Vasavilbaso decided to join the Border Patrol's peer support program after witnessing the trauma of repeatedly responding to calls from lost and dying migrants in the unforgiving desert southwest of Tucson, Arizona.

“Sometimes you go home and keep thinking you didn’t find them,” he said. “That’s why it’s so important we check on each other all the time.”

At the most recent chaplain academy, which lasted 2.5 weeks, the 15 chaplains-in-training — mostly from the Border Patrol, plus a few Fish and Wildlife Service and Bureau of Land Management officers — practiced real-life scenarios, including responding to a deadly wreck involving agents and notifying a spouse their loved one died on the job.

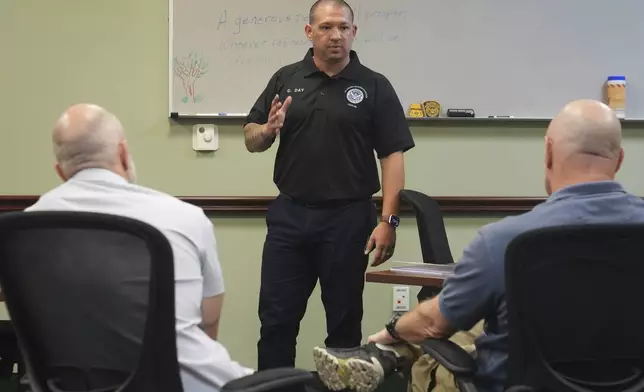

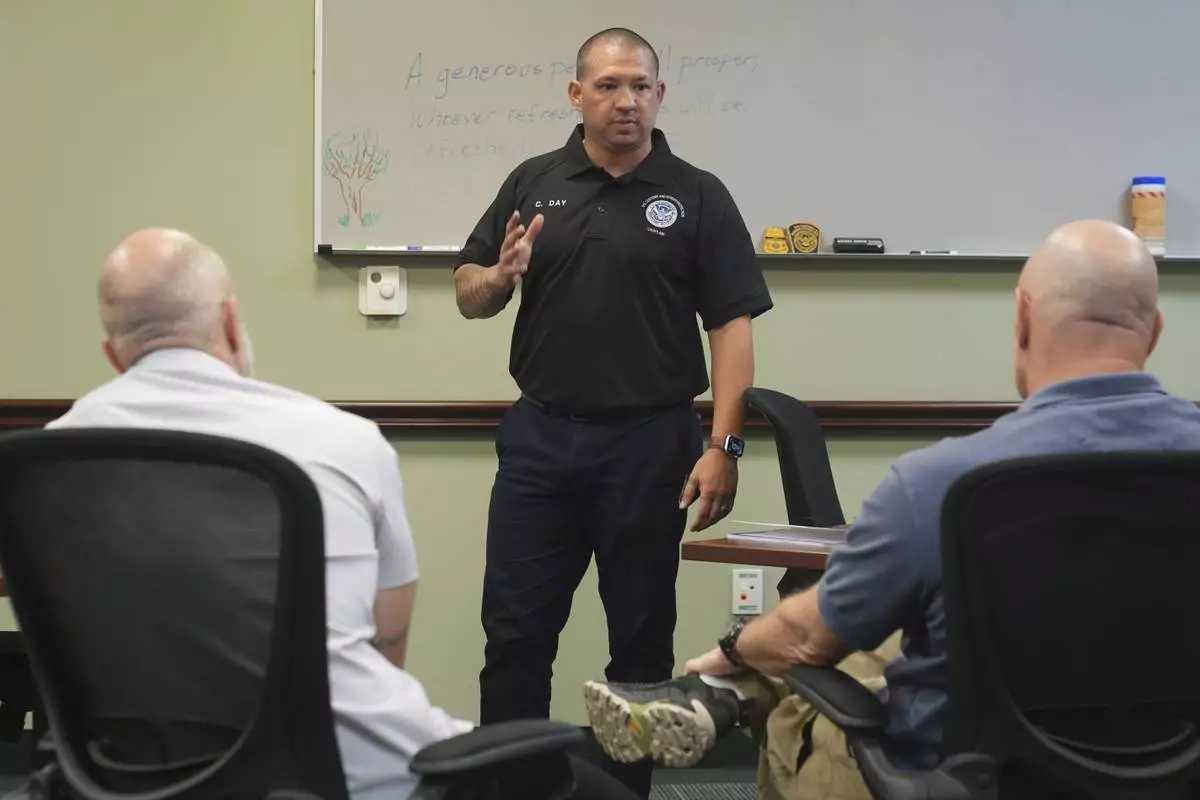

Chris Day, a chaplain since 2017, evaluated trainees trying to comfort an agent who kept screaming that it was all his fault his partner was killed. In the training scenario, their car crashed as they chased someone crossing the border illegally.

Day praised the trainees' efforts to get the agent to talk, but advised them not to say, “'I understand.' Because you don’t.”

Later, Day told the class he had helped an agent who watched the smugglers he was chasing smash their car into a family, gravely injuring a toddler. He said the agent had “ugly cried" at the scene and kept repeating that his child was the same age, so Day took him aside briefly and followed up after.

“We hugged it out,” said Day, a Baptist with a Psalm verse tattooed on his right arm.

He also has helped the wife of an agent who killed himself, and prayed for migrants who request it. More than 100 migrants have died so far this year in New Mexico's desert, where Day is stationed.

“The smells and visuals stay with you forever,” Day said. “We have empathy for people coming across.”

Trying to comfort migrant children in their custody, including the thousands who cross the border alone, is also a wrenching task for agents.

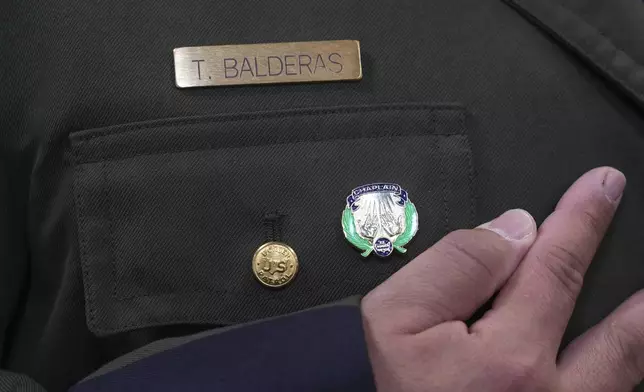

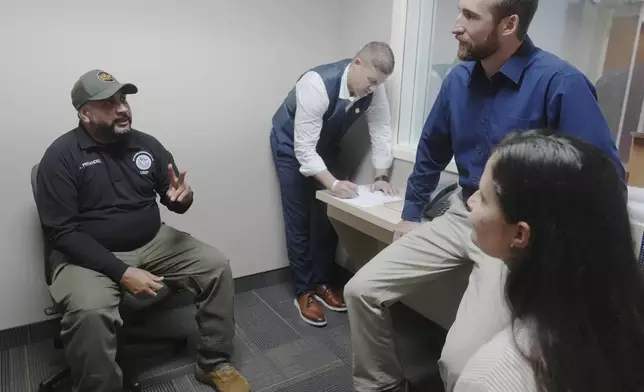

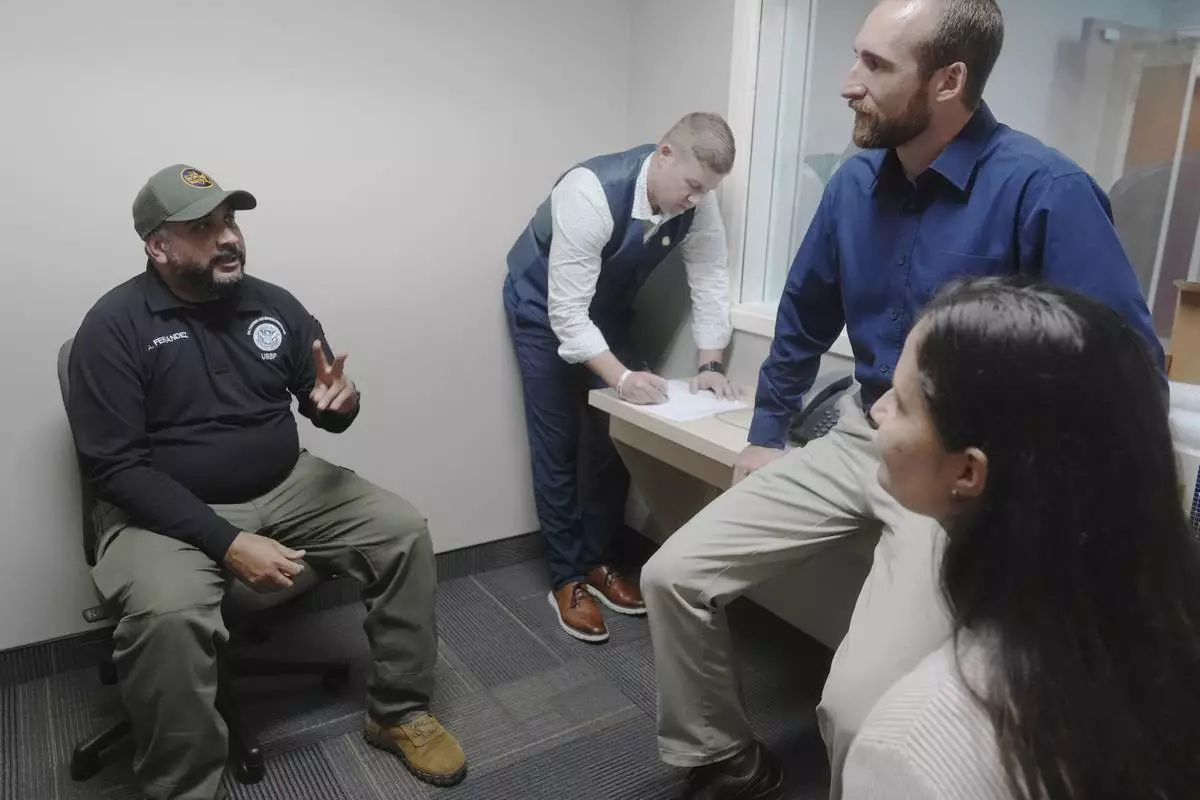

At the academy, Trinidad Balderas, a father and medic in McAllen, Texas, and Yaira Santiago, a former schoolteacher who runs a Border Patrol migrant processing center at the other end of the southern border in San Diego, California, said they both seek to provide some calm in the chaos of the children's situation.

“One tries to give them support within the limits of what your work allows. I always have the biggest smile,” Santiago said.

Border Patrol assistant chief and chaplaincy program manager Spencer Hatch highlighted the need to maintain both the “hypervigilance” of law enforcement and the humanitarian instinct to empathize with migrants and fellow agents.

He also taught strategies to protect the agents’ families from “spillover trauma.” Divorces increase when agents are redeployed during migrant surges — some up to 9 times over 18 months during the record border crossings early in the Biden Administration.

Many agents’ children are scared to reveal their parent’s job — especially in border communities. They might be going to school with children of cartel members, or of undocumented migrants, or those who see the Border Patrol as “keeping people from living the American dream,” in Hatch’s words.

“That’s a really hard thing to deal with, as things tend to flip from one side to the other, and we’re still in the crossfire,” he added.

Hatch uses as a case study of moral injury, a 2021 incident in Del Rio where agents on horseback appeared in some viral photos to be whipping immigrants with their reins — which a federal investigation later determined hadn’t happened.

“For one picture to be taken out of context and to have the highest levels of government shaming those people, that was very disheartening. That hurt all of us,” Hatch said.

Dealing with that “dissonance” of enforcing immigration laws, including rescuing migrants, and hearing their jobs demonized by the public, is a major challenge, said Tucson-area chaplain Jimmy Stout. He was one of first four chaplains when the program was started through a grassroots effort at the southern border in the late 1990s.

“We go over this on day one,” Stout said. “Is what they’re doing meeting their personal standards?”

For the agents who got their chaplain pins last week, those standards now involve a higher calling, too.

Class speaker Matt Kiniery, a father of three who joined the Army after 9/11 and the Border Patrol in El Paso, Texas, in 2009, decided to become a chaplain after an on-duty car wreck so bad the doctor called his survival miraculous.

“‘The guy upstairs has got something for you.’ I took that to heart,” Kiniery said. Chaplains helped his wife Jeanna then, and the couple is now eager to support his new role.

“Even in moments of uncertainty, your presence is often enough,” the 6-foot-5 agent told the graduating class, before his voice broke. Several instructors in the audience wiped away tears.

Associated Press religion coverage receives support through the AP’s collaboration with The Conversation US, with funding from Lilly Endowment Inc. The AP is solely responsible for this content.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife law enforcement agent is surrounded by his family following the Border Patrol Chaplain Academy graduation, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024, in Dania Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)

Border Patrol Agent Matthew A. Kiniery smiles as Chaplaincy program manager Spencer Hatch pins the chaplain pin on his uniform, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024, in Dania Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)

Border Patrol Chaplain pins are ready to be pinned during a Border Patrol Chaplain Academy graduation ceremony, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Dania Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)

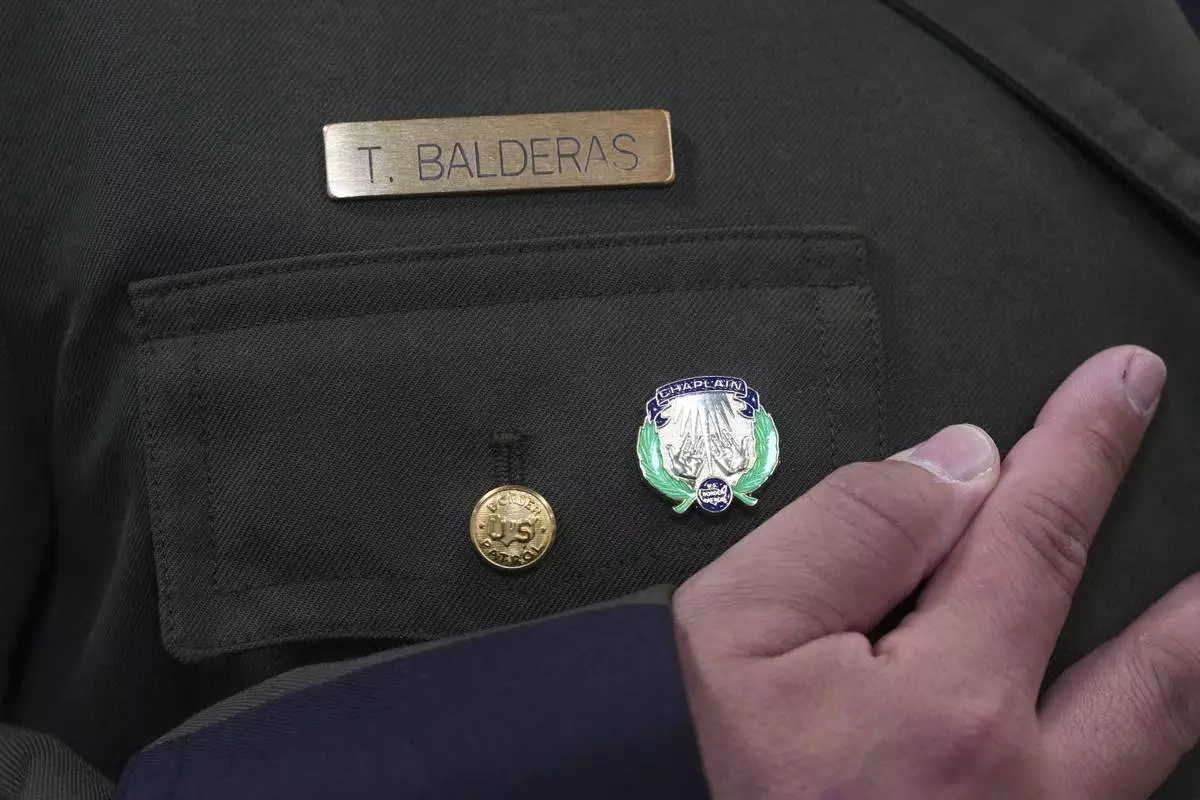

Border Patrol Agent Trinidad Balderas looks at his new chaplain pin after graduating from the program, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024, in Dania Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)

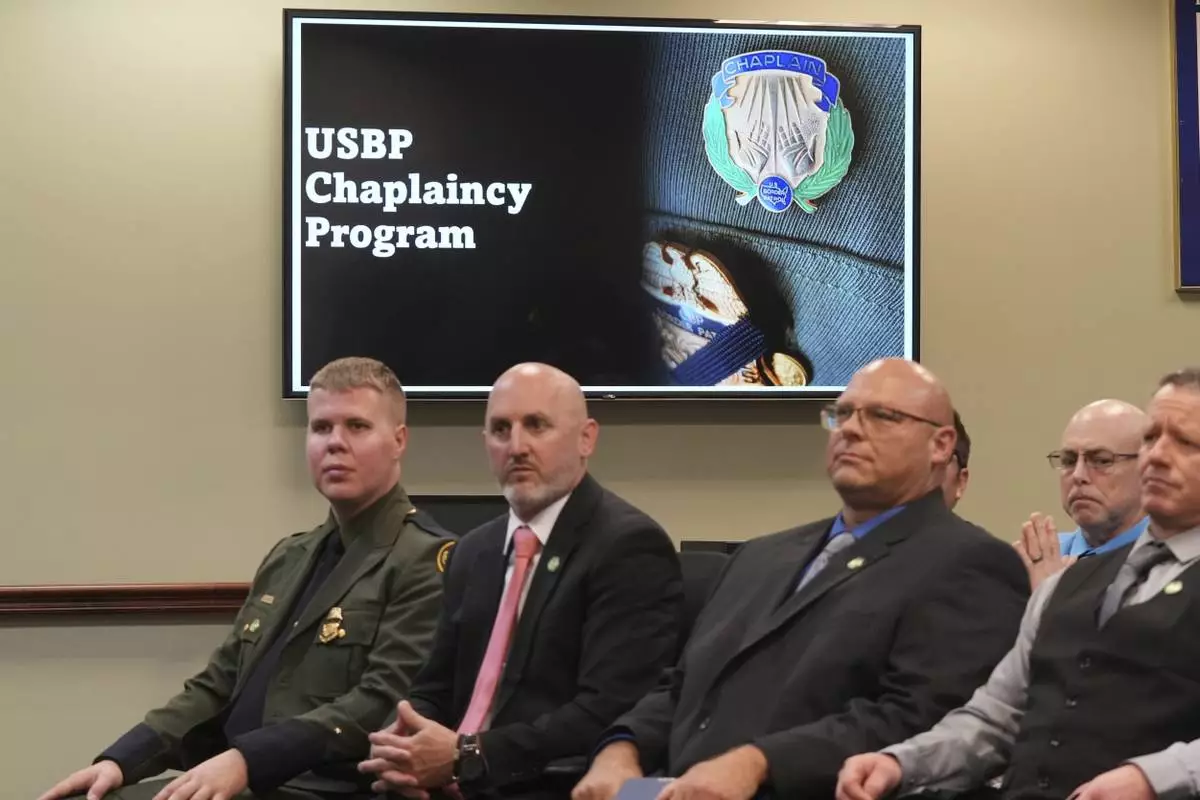

The USBP chaplaincy program class listen to remarks during their graduation, Thursday, Nov. 21, 2024, in Dania Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)

Border Patrol chaplain and instructor Jason Wilhite holds two Silent Partner cards he carries with him at all times showing two of his colleagues that died in the line of duty, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Dania Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)

U.S. Border Patrol agent Jesus Vasavilbaso, aided by a Black Hawk helicopter, searches for a group of migrants evading capture in the desert brush at the base of the Baboquivari Mountains, Thursday, Sept. 8, 2022, near Sasabe, Ariz. (AP Photo/Matt York, File)

Border Patrol instructor and Chaplain Christopher Day directs a session at the Border Patrol Chaplain Academy, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Dania Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)

Border Patrol specialist Mitchell Holmes, left, listens to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Regional Law Enforcement agent Kevin Shinn, during a Chaplain Academy training session, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Dania Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)

Border Patrol Chaplaincy program manager Spencer Hatch teaches during the Border Patrol Chaplain Academy class, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Dania Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)

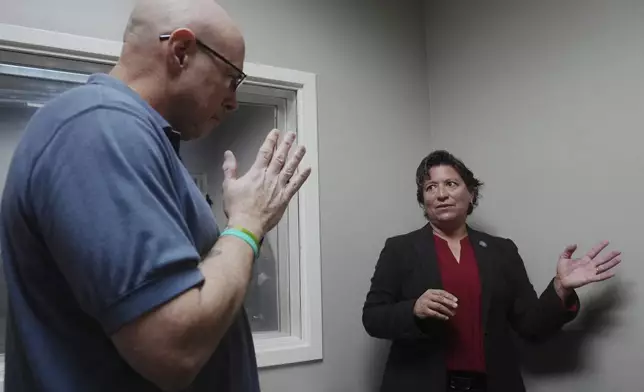

Federal Wildlife Officer Cody Smith and Border Patrol processing coordinator Yaira Santiago listen to Border Patrol agent Andry Fernandez during a training scenario where they practice their new chaplain skills, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Dania Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)

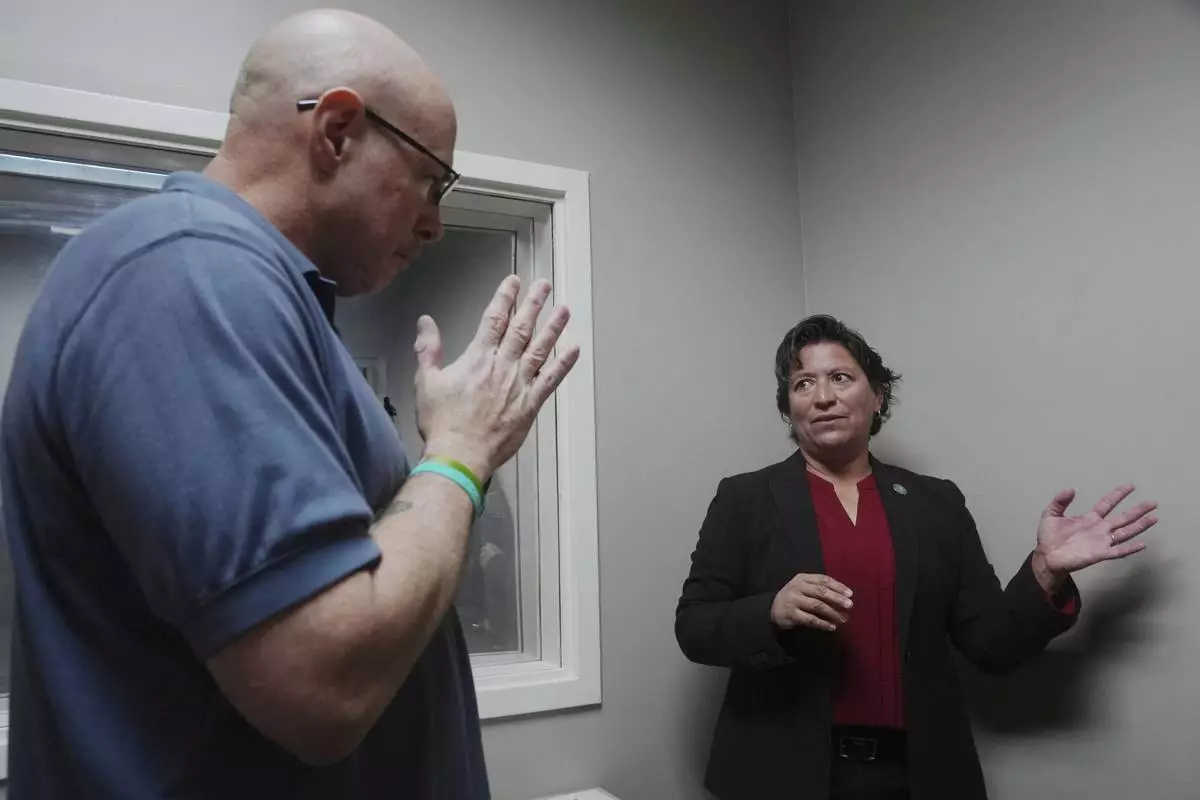

Border Patrol specialist Mitchell Holmes listens to instructor and chaplain Myrna Gonzalez during a training session, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Dania Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)

Border Patrol processing coordinator Yaira Santiago listens to Federal Wildlife officer Cody Smith during a scenario training session, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Dania Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)

Border Patrol specialist Mitchell Holmes, right, and Fish and Wildlife Regional Law Enforcement agent Kevin Shinn, use skills they learned in the Border Patrol Chaplaincy academy during a training session, Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2024, in Dania Beach, Fla. (AP Photo/Marta Lavandier)