NEW YORK (AP) — An Alabama woman is recovering well after a pig kidney transplant last month that freed her from eight years of dialysis, the latest effort to save human lives with animal organs.

Towana Looney is the fifth American given a gene-edited pig organ — and notably, she isn’t as sick as prior recipients who died within two months of receiving a pig kidney or heart.

“It’s like a new beginning,” Looney, 53, told The Associated Press. Right away, “the energy I had was amazing. To have a working kidney — and to feel it — is unbelievable.”

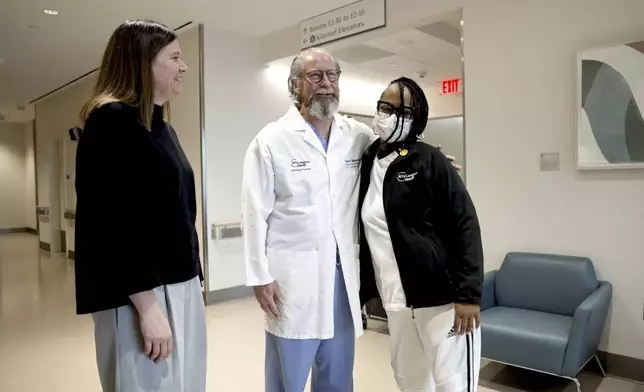

Looney’s surgery marks an important step as scientists get ready for formal studies of xenotransplantation expected to begin next year, said Dr. Robert Montgomery of NYU Langone Health, who led the highly experimental procedure on Nov. 25.

On Tuesday, NYU announced that Looney is recuperating well. She was discharged from the hospital just 11 days after surgery although she was temporarily readmitted this week to adjust her medications. Doctors expect her to return home to Gadsden, Alabama, in three months. If the pig kidney were to fail, she could begin dialysis again.

“To see hope restored to her and her family is extraordinary,” said Dr. Jayme Locke, Looney's original surgeon who secured Food and Drug Administration permission for the transplant.

More than 100,000 people are on the U.S. transplant list, most who need a kidney. Thousands die waiting and many more who need a transplant never qualify. Now, searching for an alternate supply, scientists are genetically altering pigs so their organs are more humanlike.

Looney donated a kidney to her mother in 1999. Later pregnancy complications caused high blood pressure that damaged her remaining kidney, which eventually failed. It’s incredibly rare for living donors to develop kidney failure although those who do are given extra priority on the transplant list.

But Looney couldn't get a match — she had developed antibodies abnormally primed to attack another human kidney. Tests showed she’d reject every kidney donors have offered.

Then Looney heard about pig kidney research at t he University of Alabama at Birmingham and told Locke, at the time a UAB transplant surgeon, she'd like to try one. In April 2023, Locke filed an FDA application seeking an emergency experiment, under rules for people like Looney who are out of options.

The FDA didn't agree right away. Instead, the world's first gene-edited pig kidney transplants went to two sicker patients last spring, at Massachusetts General Hospital and NYU. Both also had serious heart disease. The Boston patient recovered enough to spend about a month at home before dying of sudden cardiac arrest deemed unrelated to the pig kidney. NYU’s patient had heart complications that damaged her pig kidney, forcing its removal, and she later died.

Those disappointing outcomes didn’t dissuade Looney, who was starting to feel worse on dialysis but, Locke said, hadn't developed heart disease or other complications. The FDA eventually allowed her transplant at NYU, where Locke collaborated with Montgomery.

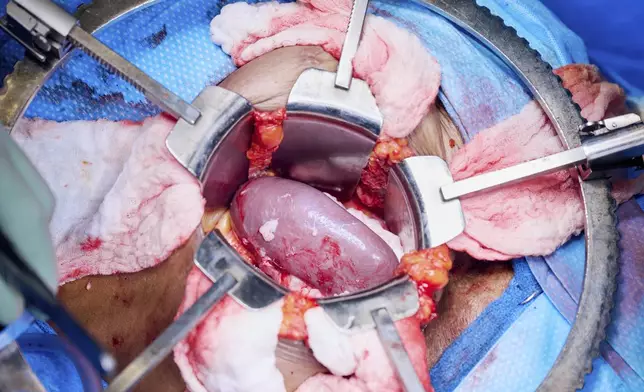

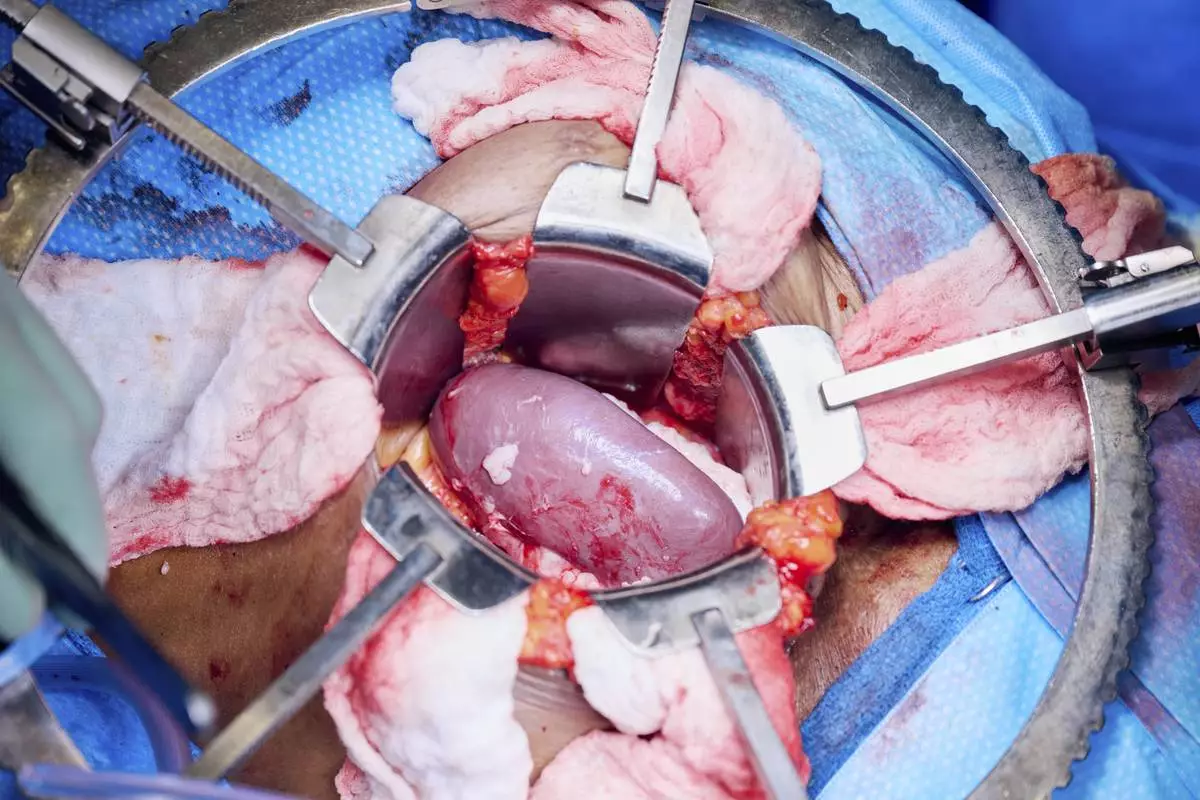

Moments after Montgomery sewed the pig kidney into place, it turned a healthy pink and began producing urine.

Even if her new organ fails, doctors can learn from it, Looney told the AP: “You don't know if it's going to work or not until you try.”

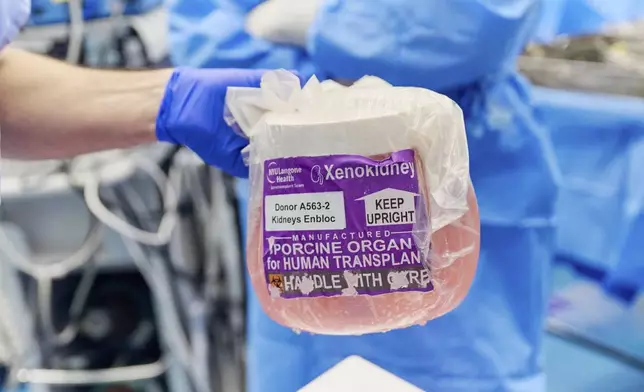

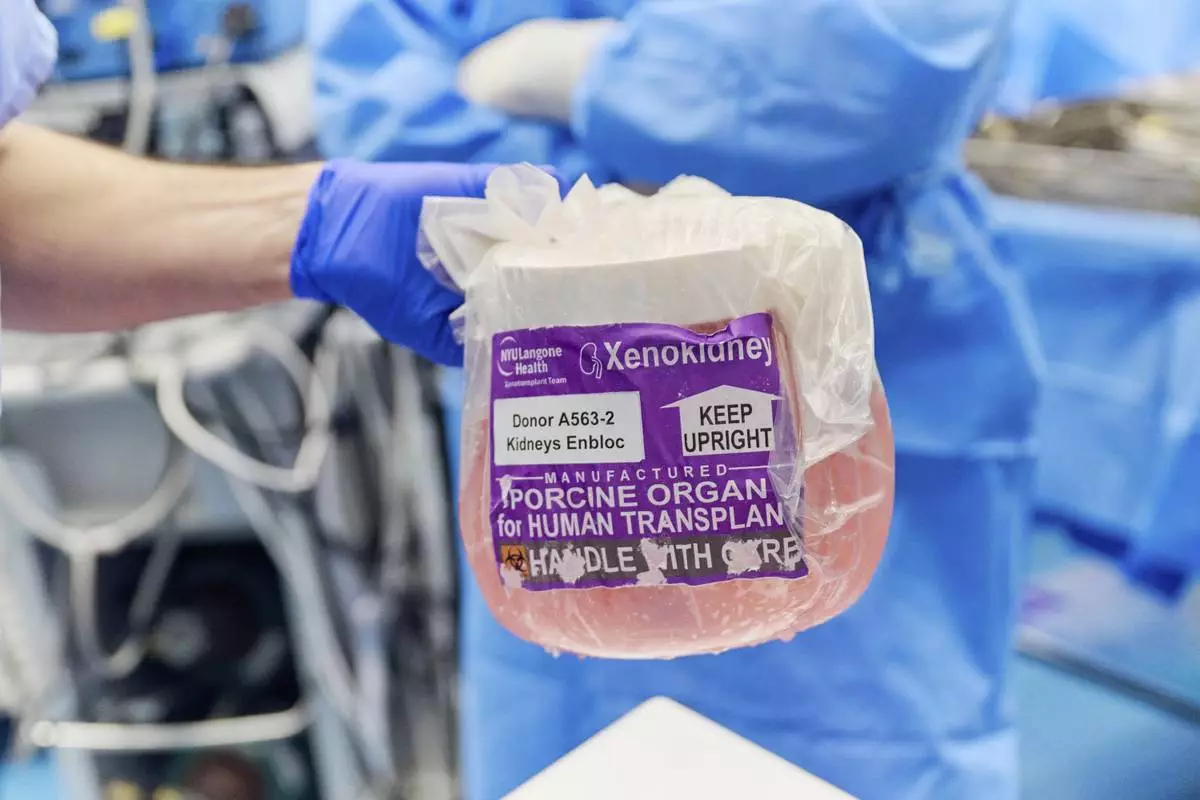

Blacksburg, Virginia-based Revivicor provided Looney’s new kidney from a pig with 10 gene alterations. Its parent company, United Therapeutics said Tuesday it plans to file an application with the FDA “very soon” to begin clinical trials with that type of kidney.

Looney was initially discharged on Dec. 6, wearing monitors to track her blood pressure, heart rate and other bodily functions and returning to the hospital for daily checkups before her medication readmission. Doctors scrutinize her bloodwork and other tests, comparing them to prior research in animals and a few humans in hopes of spotting an early warning if problems crop up.

“A lot of what we’re seeing, we’re seeing for the first time,” Montgomery said.

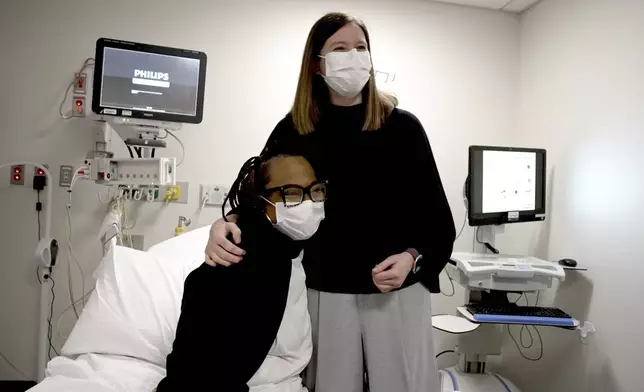

Locke, who recently joined the federal Health Resources and Services Administration, visited last week to check her longtime patient's progress. Looney hugged her, saying, “Thank you for not giving up on me.”

“Never,” Locke responded.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

The gene-edited pig kidney moments after blood vessels are reattached and the organ is reperfused with Towana Looney’s blood at NYU Langone Health in New York City on Nov. 25, 2024. (Joe Carrotta/NYU Langone Health via AP)

The gene-edited pig kidney is removed from its package in the operating room at NYU Langone Health in New York City on Nov. 25, 2024. (Joe Carrotta for NYU Langone Health via AP)

Kryscilla J. Yang, MD, clinical instructor for the NYU Langone Transplant Institute (from left) and Robert Montgomery, MD, DPhil, the H. Leon Pachter, MD, Professor of Surgery, chair of the NYU Grossman School of Medicine Department of Surgery, and director of the NYU Langone transplant Institute,bprepare patient Towana Looney to receive a gene-edited pig kidney at NYU Langone Health in New York City on Nov. 25, 2024. (Joe Carrotta/NYU Langone Health via AP)

Robert Montgomery, MD, DPhil, the H. Leon Pachter, MD, Professor of Surgery, chair of the NYU Grossman School of Medicine Department of Surgery, and director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute, reviews a monitor during the gene-edited pig kidney transplant surgery at NYU Langone Health in New York City on Nov. 25, 2024. (Joe Carrotta/NYU Langone Health via AP)

Pig kidney recipient Towana Looney sits with transplant surgeons Dr. Jayme Locke on Dec. 10, 2024, at NYU Langone Health, in New York City. (AP Photo/Shelby Lum)

Pig kidney recipient Towana Looney is visited by Dr. Robert Montgomery of NYU Langone Health, center, on Dec. 10, 2024, at NYU Langone Health, in New York City. (AP Photo/Shelby Lum)

Pig kidney recipient Towana Looney stands with transplant surgeons Dr. Jayme Locke, left, now of the U.S. Health Resources & Services Administration and Dr. Robert Montgomery of NYU Langone Health, center, on Dec. 10, 2024, at NYU Langone Health, in New York City. (AP Photo/Shelby Lum)