TAPACHULA, Mexico (AP) — A new caravan of migrants began walking from southern Mexico on Thursday toward the U.S. border, starting out from the city of Tapachula near the border with Guatemala.

The majority of the migrants are from Venezuela, but they also include people from Guatemala, El Salvador, Peru and Ecuador. They've said they are tired of being blocked from crossing Mexico by the government.

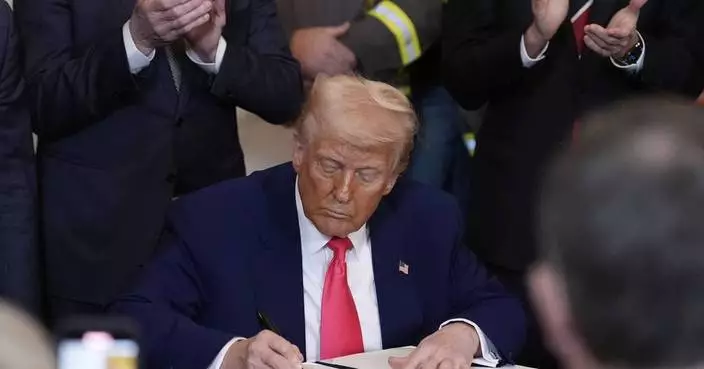

Though previous caravans have said they intend to reach the border — something that was almost never achieved — the migrants in the new caravan appear to be less clear about where they were headed. President-elect Donald Trump has pledged to prevent migrants from entering the United States and stage mass deportations of those already in the country.

Many of the migrants said they were simply tired of being bottled up in Tapachula — a city tired of hosting thousands of migrants and one where they cannot find much work.

Giscarlis Colmenares, a 29-year-old from Venezuela, has been waiting for almost three months for an asylum appointment through the U.S. CBP One app.

Colmenares said her immediate goal was to reach Mexico City to find “work, so that we see whether we can get, ahead, or stay here and earn enough money to return to Venezuela.”

An improvised migrant camp in downtown Mexico City was already full to overflowing with migrants.

Some recognized the difficulties involved in reaching the U.S.

Douglas Ernesto, from El Salvador, trudged along with the caravan on Thursday, with his wife and 10-year-old son.

“Our goal is the United States, but if not, we'll stay in Mexico,” Ernesto said, acknowledging “that getting beyond Tapachula is very difficult.”

The caravan has little or no chance of making it more than a few dozen miles. In November, Mexican officials broke up two similar migrant caravans not far from Tapchula.

Apart from the much larger first caravans in 2018 and 2019 — which were provided buses to ride part of the way north — no caravan has ever reached the U.S. border walking or hitchhiking in any cohesive way, though some individuals have made it.

For years, migrant caravans have often been blocked, harassed or prevented from hitching rides by Mexican police and immigration agents. They have also frequently been rounded up or returned to areas near the Guatemalan border.

Migrants walk through Tapachula, Chiapas state, Mexico, Thursday, Jan. 2, 2025, as part of a caravan trying to reach the U.S. border. (AP Photo/Edgar H. Clemente)

A migrant sleeps on a park bench in Huehuetan, Chiapas state, Mexico, Thursday Jan. 2, 2025, as his caravan makes a rest stop on its way by foot to the U.S. border. (AP Photo/Edgar H. Clemente)

Migrants walk through Tapachula, Chiapas state, Mexico, Thursday, Jan. 2, 2025, in an attempt to reach the U.S. border. (AP Photo/Edgar H. Clemente)

A migrant carries a child through Tapachula, Chiapas state, Mexico, Thursday, Jan. 2, 2025, as part of a caravan of migrants trying to reach the U.S. border. (AP Photo/Edgar H. Clemente)

WASHINGTON (AP) — The Supreme Court on Thursday said the Trump administration must facilitate the return of a Maryland man who was mistakenly deported to prison in El Salvador, rejecting the administration’s emergency appeal.

The court acted in the case of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, a Salvadoran citizen who had an immigration court order preventing his deportation to his native country over fears he would face persecution from local gangs.

U.S. District Judge Paula Xinis had ordered Abrego Garcia, now being held in a notorious Salvadoran prison, returned to the United States by midnight Monday.

“The order properly requires the Government to ‘facilitate’ Abrego Garcia’s release from custody in El Salvador and to ensure that his case is handled as it would have been had he not been improperly sent to El Salvador,” the court said in an unsigned order with no noted dissents.

Chief Justice John Roberts had already pushed back Xinis' deadline, and the justices said that her order must now be clarified to make sure it doesn’t intrude into executive branch power over foreign affairs, since Abrego Garcia is being held abroad. The court said the Trump administration should also be prepared to share what steps it has taken to try and get him back — and what more it could potentially do.

The administration claims Abrego Garcia is a member of the MS-13 gang, though he has never been charged with or convicted of a crime. His attorneys said there is no evidence he was in MS-13.

The administration has conceded that it made a mistake in sending him to El Salvador, but argued that it no longer could do anything about it.

The court’s liberal justices said the administration should have hastened to correct “its egregious error” and was “plainly wrong” to suggest it could not bring him home.

“The Government’s argument, moreover, implies that it could deport and incarcerate any person, including U. S. citizens, without legal consequence, so long as it does so before a court can intervene,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote, joined by her two colleagues.

In the district court, Xinis wrote that the decision to arrest Abrego Garcia and send him to El Salvador appears to be “wholly lawless.” There is little to no evidence to support a “vague, uncorroborated” allegation that Kilmar Abrego Garcia was once in the MS-13 street gang, Xinis wrote.

Abrego Garcia, 29, was detained by immigration agents and deported last month.

He had a permit from the Homeland Security Department to legally work in the U.S. and was a sheet metal apprentice pursuing a journeyman license, his attorney said. His wife is a U.S. citizen.

In 2019, an immigration judge barred the U.S. from deporting Abrego Garcia to El Salvador, finding that he faced likely persecution by local gangs.

A Justice Department lawyer conceded in a court hearing that Abrego Garcia should not have been deported. Attorney General Pam Bondi later removed the lawyer, Erez Reuveni, from the case and placed him on leave.

Associated Press writer Lindsay Whitehurst contributed to this report.

Jennifer Vasquez Sura, the wife of Kilmar Abrego Garcia of Maryland, who was mistakenly deported to El Salvador, speaks during a news conference at CASA's Multicultural Center in Hyattsville, Md., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/Jose Luis Magana)