LOS ANGELES (AP) — A woman who worked as a hairstylist for Fox Sports alleges in a lawsuit that former host Skip Bayless made repeated, unwanted advances toward her — including an offer of $1.5 million to have sex with him.

Attorneys for Noushin Faraji, who was a hair stylist at Fox for more than a decade, are seeking unspecified damages from Bayless, Fox Sports and its parent company, Fox Corporation, according to a copy of the lawsuit filed Friday in California Superior Court in Los Angeles.

The complaint claims Fox executives fostered a hostile work environment that allowed senior managers and on-air personalities including Bayless to abuse workers without fear of punishment.

The Associated Press does not generally identify, in text or images, those who say they have been sexually assaulted or subjected to abuse unless they have publicly identified themselves as Faraji has in filing the lawsuit.

An attorney for Bayless, Jared Levine, did not immediately respond to AP's telephone and text messages seeking comment. Email and phone messages left at Bayless's talent company were not immediately returned.

Bayless could not be reached directly for comment.

Fox Sports said in a statement that it takes the allegations seriously but had no further comment given the pending lawsuit.

Faraji claimed that the advances by Bayless, which began in 2017 and continued until last year — included lingering hugs, kisses on the cheek and comments from Bayless that he could change Faraji's life if she had sex with him.

In 2021, she claims in the suit, Bayless offered Faraji $1.5 million for sex and, after she refused, later threatened her job.

“Ms. Faraji knew that he was trying to pressure her into having sex with him, but she kept repeating that she was a professional that had to be kind to all talent,” the lawsuit says.

Bayless worked for Fox Sports until 2024 when his show was canceled after its ratings plummeted with the departure of his co-host, Shannon Sharpe.

Faraji said she was fired in 2024 based on “fabricated" reasons. The lawsuit said she initially remained quiet about her treatment at Fox, believing she could be in danger if she went public.

The suit also claims Fox employees were not paid their full wages or overtime. It seeks class-action status on behalf of other workers who allegedly were impacted.

In 2017 Fox Sports fired its head of programming amid a probe of sexual harassment allegations.

FILE - A FOX Sports banner is viewed behind the end zone before an NFL football game between the Jacksonville Jaguars and the Houston Texans, Dec. 1, 2024, in Jacksonville, Fla. (AP Photo/Phelan M. Ebenhack, File)

OUAGADOUGOU, Burkina Faso (AP) — Their loved ones were slaughtered by Islamic extremists or government-affiliated fighters. Their villages were attacked, their homes destroyed. Exhausted and traumatized, they fled in search of safety, food and shelter.

This is the reality for over 2.1 million displaced people across the West African nation of Burkina Faso, torn apart by years of extreme violence.

But unlike others displaced in the region, they are seen as a challenge to Burkina Faso's military junta that took power two years ago on the pledge of bringing stability. Their existence contradicts its official narrative: that security is improving and people are safely returning home.

Those who fled to Ouagadougou, the capital, which has been shielded from violence, find fear instead of respite. They are made into shadows, with many resorting to begging. Most of them are not entitled to support from authorities, and international aid organizations are not authorized to work with them.

The Associated Press reached out to several international aid groups, Western diplomats and the United Nations. None would speak on the record about the issue.

With no official displacement sites in Ouagadougou, no one knows how many people shelter in the capital or sleep on the streets. A rare acknowledgement of their existence by authorities noted 30,000 last year.

But aid groups say real numbers are much higher. And as violence increases, and people crowd displacement sites in the country's remote north and east, exposed to hunger and disease, more are expected to arrive in the capital.

One aid worker, speaking like others on condition of anonymity for fear of retaliation, described the situation as “a ticking bomb.”

The AP interviewed four displaced people in Ouagadougou. All spoke at great risk. Three are with the Fulani ethnic group, which authorities accuse of being affiliated with Islamic insurgents. All three said they have faced discrimination in the capital, with trouble finding jobs and sending children to school.

For decades, the Fulani were neglected by the central government, and some did join miitants. As a result, Fulani civilians are often targeted both by the extremists — affiliated with al-Qaida or the Islamic State group — and by rival pro-government forces.

A 27-year-old Fulani cattle trader from Djibo, a city besieged by armed groups since 2022, who spoke on condition of anonymity for fear of repercussions from authorities, said government-affiliated forces indiscriminately treated all Fulani in the area as extremists.

“They started arresting people, bringing them to the city, beating them, undressing them. It was humiliating," he said. His uncle spent seven months in prison because he received aid from a charity run by extremists in part to spread their ideology.

He said he was arrested once in Djibo and beaten by the military, with injuries so extensive that he went to the hospital. He said soldiers told him only that they were “conducting a security operation.”

According to analysts, the junta's strategy of military escalation, including mass recruitment of civilians for poorly trained militia units, has exacerbated tensions between ethnic groups. Data gathered by the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project show that militia attacks on civilians significantly increased since Capt. Ibrahim Traore took power.

The violence has radicalized some Fulanis, the cattle trader said.

“Every day, you prayed to live through the next 24 hours," he said. “This is not a life.”

He did not want to flee and leave his parents behind. But one day, his father woke him and said: “You have to leave, because if you stay, someone will just come and kill you.”

His father was later killed.

He left in a military convoy over a year ago. Life in Ouagadougou is “very difficult,” he said. He lives with extended family and relies on odd jobs to get by.

“There are mornings when I wake up and ask myself how will I get something to eat,” he said. “I used to live with dignity.”

His mother has joined him in the capital. They have not received support from the government.

A 28-year-old mother from the northwest, who also spoke on condition of anonymity, said at first the extremists came to her village and stole cattle. But last summer, they came to the market and killed several men, including her husband. Then they ordered women and children to leave.

She grabbed her children, and cooking pots, and fled. She walked for hours through the night until she reached her husband’s family home.

Ten days later, armed men were approaching. She strapped her 2-year-old daughter to her back, grabbed her 4-year-old son and left for the capital.

She said she has not received government support in Ouagadougou. She was promised a job as a cleaner but lost the offer once the employer found out she was Fulani.

She secured a place at a rare shelter for displaced women, run with Western-supplied funds by a local activist who tries to keep a low profile. She is learning how to sew and has enrolled her son in school.

“I miss my village,” she said. “But for the moment I have to wait until the violence is over.”

Her stay is precarious. The shelter is full, hosting 50 women and children. Usually, they are allowed to stay for one year. Time is running out.

The demand is enormous, the activist said, and there is less and less aid. Local authorities are wary of anyone working with displaced people.

“I don’t know for how much longer I can keep on going,” she said.

As much as 80% of Burkina Faso's territory is controlled by extremist groups and more civilians died from violence last year than in the years before, but in Ouagadougou, it is easy to forget that the government is battling an insurgency.

Busy open-air restaurants serve beer and the national dish of slowly roasted chicken. In recent months, the capital hosted a theater festival and an international arts and crafts fair. The authorities reinstated a cross-country cycling race, Tour de Faso, previously cancelled due to insecurity.

The military leadership has installed a system of de facto censorship, rights groups said, and those daring to speak up can be openly abducted, imprisoned or forcefully drafted into the army.

Burkina Faso used to be known for its vibrant intellectual life. Now, even friends are afraid to discuss politics.

“I feel like I am in prison,” said a local women’s rights activist. “Everyone distrusts each other. We fought for the freedom of speech, and now we lost everything.”

Burkina Faso's authorities did not respond to questions.

This story corrects the number of the displaced.

The Associated Press receives financial support for global health and development coverage in Africa from the Gates Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

FILE - People ride their scooters in the Gounghin district of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, Jan. 26, 2022. (AP Photo/Sophie Garcia, File)

FILE - A mural reading "Stay vigilant and mobilized" is seen in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, March 1, 2023. (AP Photo, File)

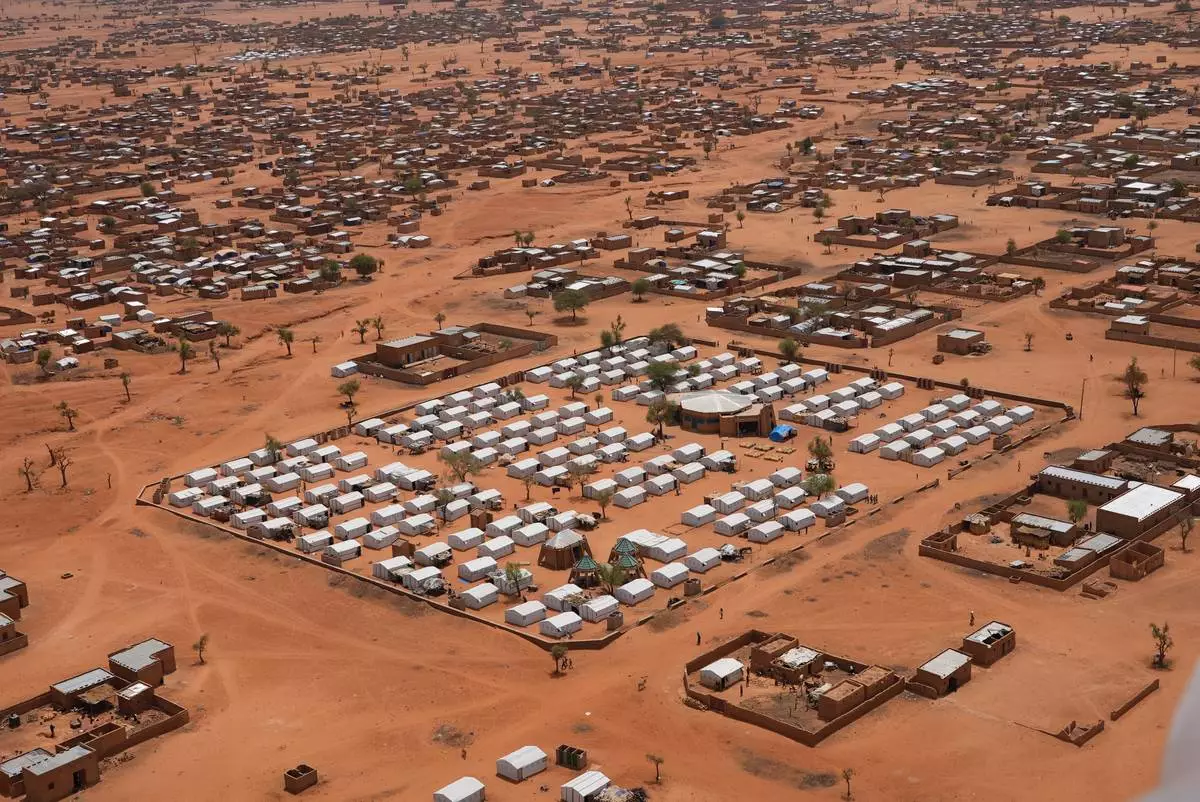

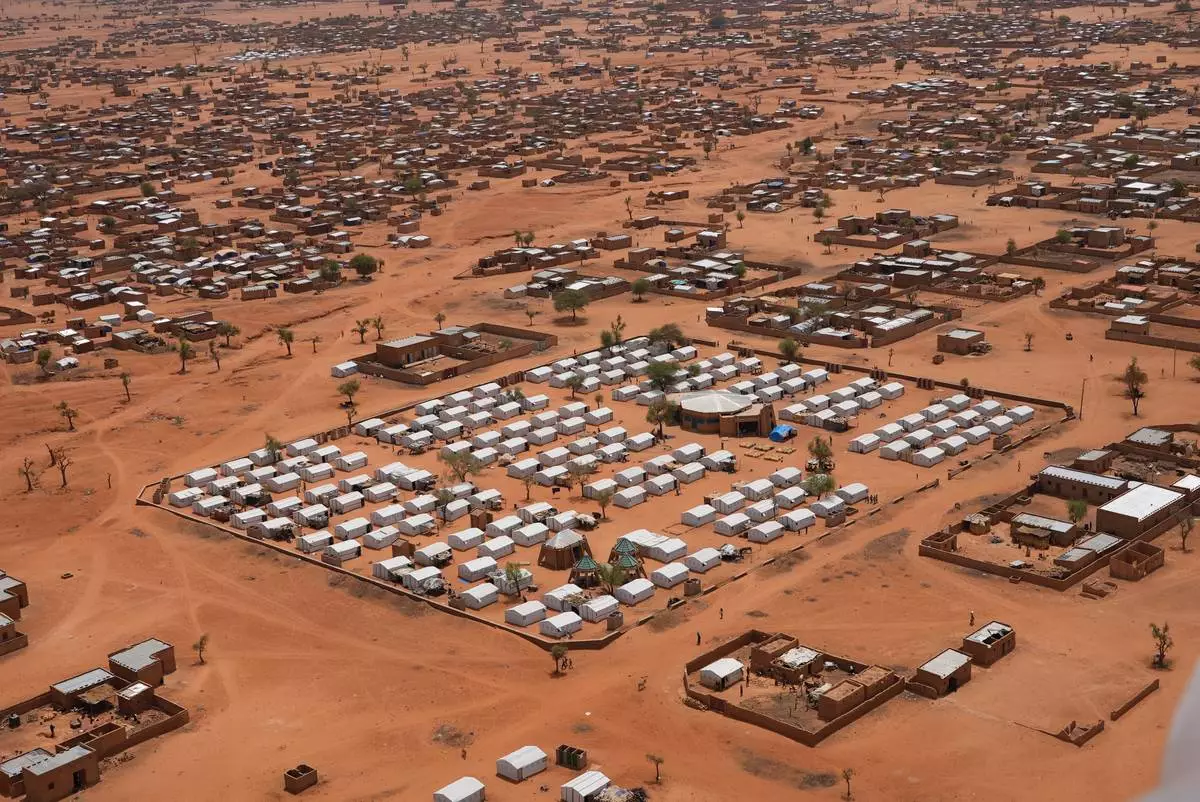

FILE - An aerial view shows a camp of internally displaced people in Djibo, Burkina Faso, May 26, 2022. (AP Photo/Sam Mednick, File)

FILE - Burkina Faso junta leader Ibrahim Traore participates in a ceremony in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, Oct. 15, 2022. (AP Photo/Kilaye Bationo, File)

FILE - Internally displaced people wait for aid in Djibo, Burkina Faso, May 26, 2022, when violence linked to al-Qaida and the Islamic State group began surging and spreading across the West African nation. (AP Photo/Sam Mednick, File)