PLAINS, Ga. (AP) — The world knew Jimmy Carter as a president and humanitarian, but he also was a woodworker, painter and poet, creating a body of artistic work that reflects deeply personal views of the global community — and himself.

His portfolio illuminates his closest relationships, his spartan sensibilities and his place in the evolution of American race relations. And it continues to improve the finances of The Carter Center, his enduring legacy.

Creating art provided “the rare opportunity for privacy” in his otherwise public life, Carter said. “These times of solitude are like being in another very pleasant world.”

Mourners at Carter’s hometown funeral will see the altar cross he carved in maple and collection plates he turned on his lathe. Great-grandchildren in the front pews at Maranatha Baptist Church slept as infants in cradles he fashioned.

The former president measured himself a “fairly proficient” craftsman. Chris Bagby, an Atlanta woodworker whose shop Carter frequented, elevated that assessment to “rather accomplished.”

Carter gleaned the basics on his father’s farm, where the Great Depression meant being a jack-of-all-trades. He learned more in shop class and with Future Farmers of America. “I made a miniature of the White House,” he recalled, insisting it was not about his ambitions.

During his Navy years, Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter chose unfurnished military housing to stretch his $300 monthly wage, and he built their furniture himself in a shop on base.

As president, Carter nurtured woodworking rather than his golf game, spending hours in a wood shop at Camp David to make small presents for family and friends. And when he left the White House, West Wing aides and Cabinet members pooled money for a shopping spree at Sears, Roebuck & Co. so he could finally assemble a full-scale home woodshop.

“One of the best gifts of my life,” Carter said.

Working in their converted garage, he previewed decades of Habitat for Humanity work by refurbishing their one-story house in Plains. He also improved his fine woodworking skills, joining wood without nails or screws. He also bought Japanese carving tools, and fashioned a chess set later owned by a Saudi prince.

Carter frequented Atlanta’s Highland Woodworking, a shop replete with a library of how-to books and hard-to-find tools, and recruited the world’s preeminent handmade furniture maker, Tage Frid, as an instructor, Bagby said.

Still hanging near the store entrance is a picture of Frid, who died in 2004, teaching students including a smiling former president at the front of the class.

“He was like a regular customer,” Bagby said, other than the “Secret Service agents who came with him.”

Carter built four ladder-back chairs out of hickory in 1983, and Sotheby’s auctioned them for $21,000 each at the time, the first of many sales of Carter paintings and furniture that raised millions to benefit The Carter Center.

It was rarely about the money, though. Jill Stuckey, a longtime friend who would have the Carters over to her home in Plains, recalled seeing the former president carrying out one of her chairs.

“I said, ‘What are you doing?’” she recalled. “He said, ‘It’s broken. I’m going to take it home and fix it.’”

He was at her back door at 7:30 the next morning, holding her repaired chair.

Carter compared woodworking to the results of his labor as a Navy engineer, or as a boy on the farm: “I like to see what I have done, what I have made.”

Carter employed a folk-art style as a late-in-life amateur painter and claimed “no special talent,” but a 2020 Carter Center auction drew $340,000 for his painting titled “Cardinals,” and his oil-on-canvas of an eagle sold for $225,000 in 2023, months after he entered hospice care.

Carter’s work hangs throughout the center’s campus. A room where he met with dignitaries is encircled with birds he painted after he and Rosalynn took on bird watching as a hobby.

Near the executive offices are a self-portrait and a painting of Rosalynn in their early post-presidential years, hanging across from a trio of Andy Warhol prints showing Carter in office.

Carter’s earliest years predominate, with boyhood farm scenes and portraits of influential figures like his father James Earl Carter Sr., whose death in 1953 led him to abandon a Navy career and eventually enter politics in Georgia.

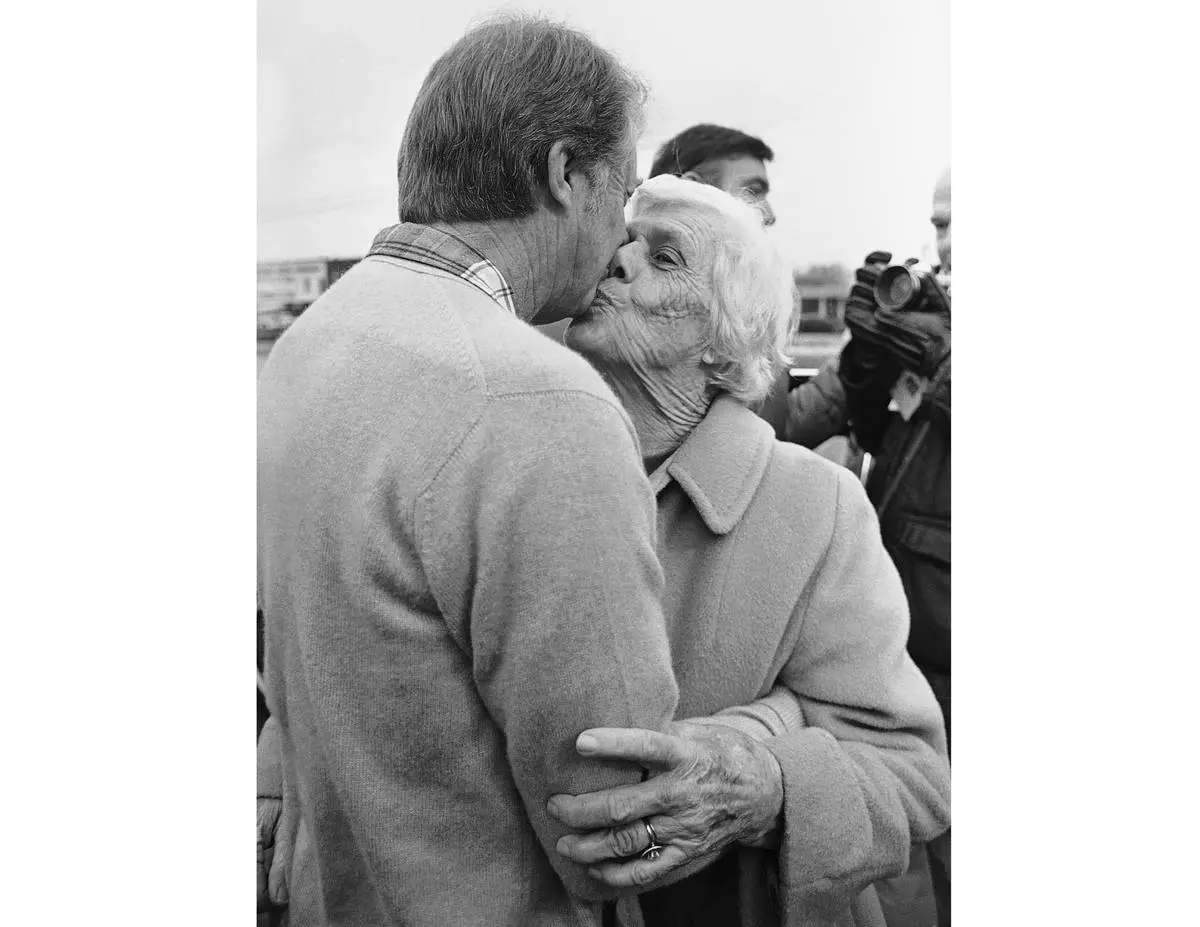

Some of his subjects, including both of his parents, are looking away. Carter's likeness of his mother shows “Miss Lillian” as a 70-year-old Peace Corps volunteer in India. Jason Carter said the piece was particularly meaningful to his grandfather, who lost reelection at a relatively youthful 56.

“When he got out of the White House, she was standing there saying, ’Well, I turned 70 in the Peace Corps. What are you going to do?” Jason Carter said.

One Carter subject who meets his gaze is a young Rosalynn — they married when she was 18 and he was 21. He described her as “remarkably beautiful, almost painfully shy, obviously intelligent, and yet unrestrained in our discussions.”

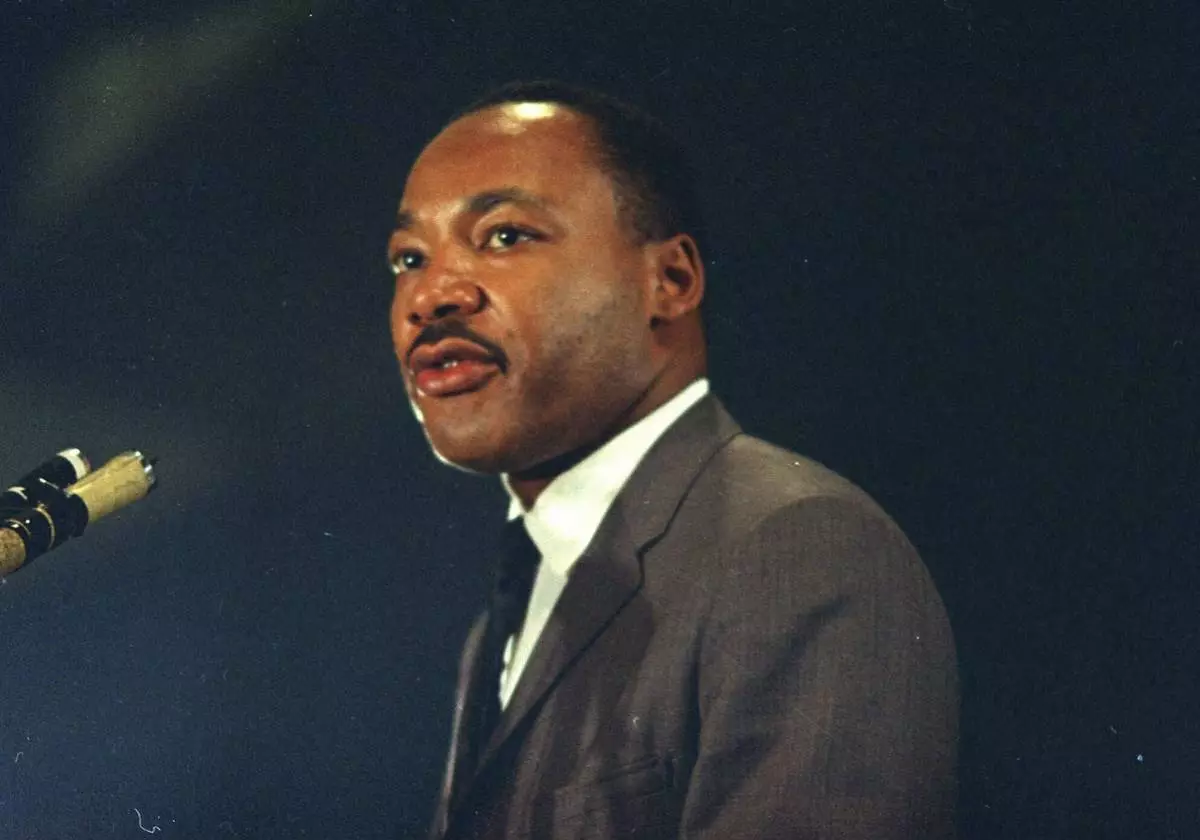

Another who doesn’t look away is Rachel Clark, a Black sharecropper who had hosted the future president after they worked in the fields. “Except for my parents, Rachel Clark was the person closest to me,” Carter wrote of his childhood.

Carter wrote more than 30 books — even a novel — but was most introspective in poetry.

On his first real recognition of Jim Crow segregation: “A silent line was drawn between friend and friend, race and race.”

On his Cold War submarine’s delicate dance with enemies: “We wanted them to understand ... to share our love of solitude ... the peace we yearned to keep.”

Rosalynn’s smile, he gushed, silenced the birds, “or may be I failed to hear their song.”

Perhaps Carter’s most revealing poem, “I Wanted to Share My Father’s World,” concerns the man who never got to see his namesake son’s achievements. He wrote that he despised Earl’s discipline, and swallowed hunger for “just a word of praise.”

Only when he brought his own sons to visit his dying father did he “put aside the past resentments of the boy” and see “the father who will never cease to be alive in me.”

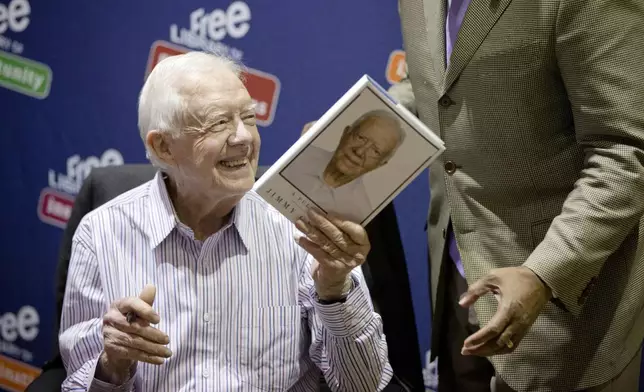

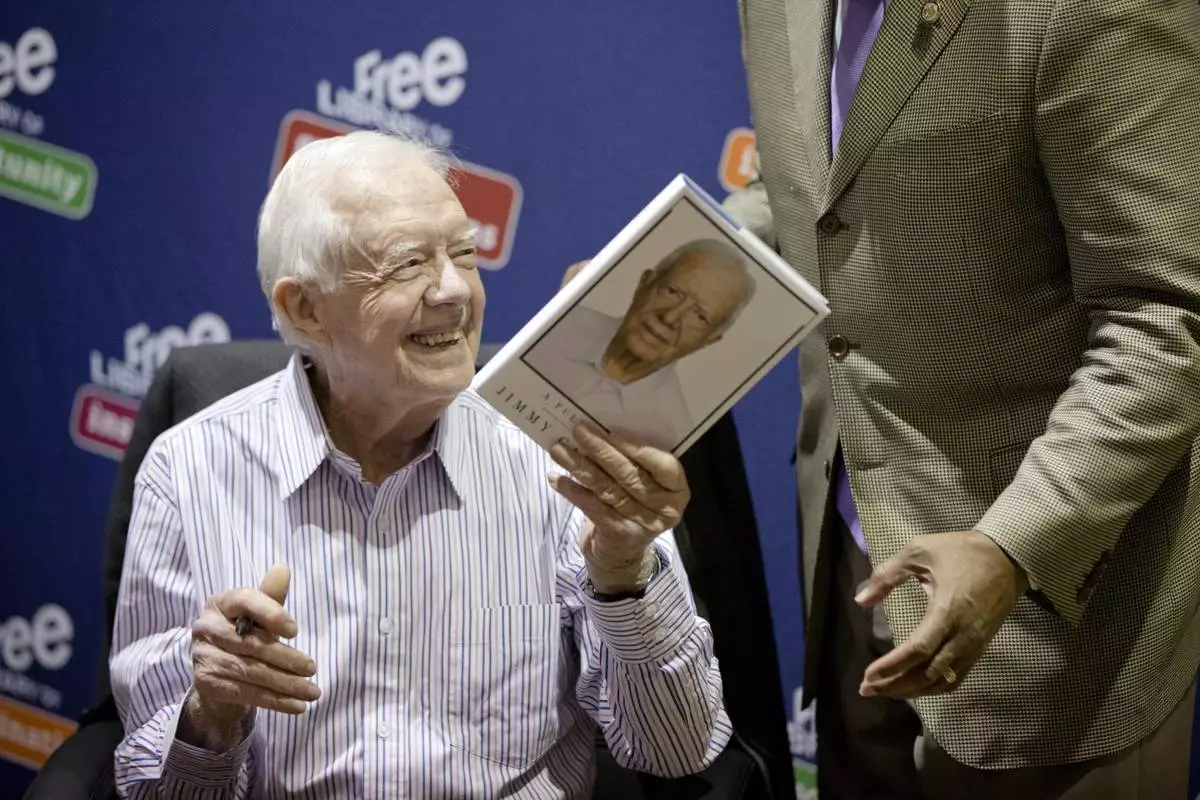

FILE - Former President Jimmy Carter hands a copy of his new book, "A Full Life: Reflections at Ninety," to Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter, on July 10, 2015, at the Free Library in Philadelphia. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke, File)

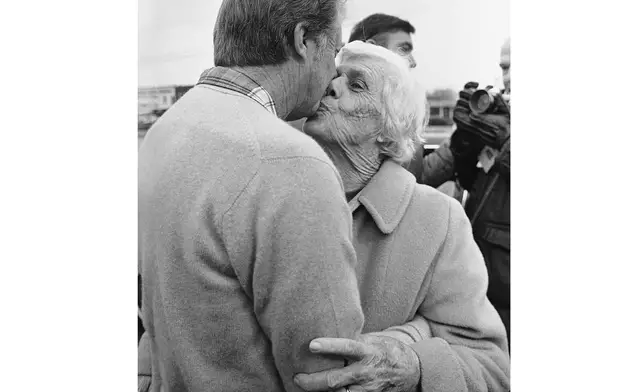

FILE - Georgia State Sen. Jimmy Carter hugs his wife, Rosalynn, at his Atlanta campaign headquarters on Sept. 15, 1966. (AP Photo, File)

FILE - President-elect Jimmy Carter gets a kiss from his mother, Lillian Carter, on Dec. 6, 1976, in Plains, Ga. (AP Photo/File)

Former Pres. Jimmy Carter marks a board to be cut as he works with the Habitat for Humanity project in Charlotte, N.C., on Monday, July 27, 1987. The group of workers plans to build 14 homes in five days. (AP Photo/Mark Humphrey)

Bouquets of flowers and peanuts are placed at the base of a bust of former President Jimmy Carter at the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum Sunday, Dec. 29, 2024, in Atlanta. (AP Photo/Brynn Anderson)

FILE - Former President Jimmy Carter answers questions during a news conference at a Habitat for Humanity building site, in Memphis, Tenn., on Nov. 2, 2015. (AP Photo/Mark Humphrey, File)