BATON ROUGE, La. (AP) — An arrest warrant has been issued for a New York doctor indicted on Friday by a Louisiana grand jury for allegedly prescribing abortion pills online to a pregnant minor in the Deep South state, which has one of the strictest near-total abortion bans in the country.

Grand jurors at the District Court for the Parish of West Baton Rouge unanimously issued an indictment against Dr. Margaret Carpenter; her company, Nightingale Medical, PC; and the minor's mother. All three were charged with criminal abortion by means of abortion-inducing drugs, a felony.

In addition to Carpenter, an arrest warrant was issued for the mother, who has not been publicly identified to protect the identity of the minor. District Attorney Tony Clayton told The Associated Press that the mother turned herself in to police on Friday.

The case appears to be the first instance of criminal charges against a doctor accused of sending abortion pills to another state, at least since the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in 2022 and opened the door for states to have strict anti-abortion laws.

“We expect Dr. Carpenter to come to Louisiana and answer to these charges, and if 12 people (a jury) think she's innocent then, let it go," Clayton said.

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul said in a video posted on social media, “I will never, under any circumstances, turn this doctor over to the state of Louisiana under any extradition requests,” signaling a potential legal battle between the states.

Last year, the Port Allen, Louisiana, woman requested abortion medication online from Carpenter for her daughter, whose age has not been specified. Clayton said the request was made through a questionnaire only and no consultation with the girl.

A “cocktail of pills” was mailed to the woman who directed her daughter to take the pill, Clayton said.

After taking the drug, the girl experienced a medical emergency while alone, called 911 and was transported to the hospital where she was treated. While responding to the emergency, a police officer learned about the pills and under further investigation found that a doctor in New York state had supplied the drugs and turned their findings over to Clayton's office.

It is unclear how far along the girl was in her pregnancy.

“The (adult) mother has since been arrested, but the other person we believe is just as culpable here is the person who sat in an office, wrapped a box of pills, put a stamp on the box and mailed it to the state of Louisiana for a child to take,” Clayton said.

Carpenter was sued in December by the Texas attorney general under similar allegations of sending pills to that state. That case did not involve criminal charges.

Carpenter did not immediately return a message from the AP.

The indictment comes just months after Louisiana became the first state with a law reclassifying both mifepristone and misoprostol as “controlled dangerous substances.” The drugs are still allowed, but medical personnel must take extra steps to access them.

Under the legislation, if someone knowingly possesses either medication without a valid prescription, they could be fined up to $5,000 and sent to jail for one to five years. The law carves out protections for pregnant women who obtain the drug without a prescription to take on their own.

“I have said it before and I will say it again: We will hold individuals accountable for breaking the law,” Louisiana Attorney General Liz Murrill, a Republican, said in a statement on Friday.

Abortion opponents and reproductive rights groups alike flooded social media scrutinizing the indictment.

“We cannot continue to allow forced birth extremists to interfere with our ability to access necessary healthcare, Chasity Wilson, executive director of the Louisiana Abortion Fund, said in a statement. “Extremists hope this case will cause a chilling effect, further tying the hands of doctors who took an oath to care for their patients.”

Since the fall of Roe v. Wade, Louisiana has had a near-total abortion ban, without any exceptions for rape or incest. Under the law, physicians convicted of performing an illegal abortion, including one with pills, face up to 15 years in prison, $200,000 in fines and the loss of their medical license.

“Make no mistake, since Roe v Wade was overturned, we’ve witnessed a disturbing pattern of interference with women’s rights,” the Abortion Coalition of Telemedicine, where Carpenter is one of the founders, said in a statement. “It’s no secret the United States has a history of violence and harassment against abortion providers, and this state-sponsored effort to prosecute a doctor providing safe and effective care should alarm everyone.”

Friday’s indictment could be the first direct test of New York’s shield laws, which are intended to protect prescribers who use telehealth to provide abortion pills to patients in states where abortion is banned. New York Attorney General Letitia James said “we will not allow bad actors to undermine our providers’ ability to deliver critical care.”

“This cowardly attempt out of Louisiana to weaponize the law against out-of-state providers is unjust and un-American,” James added.

Pills have become the most common means of abortion in the U.S., accounting for nearly two-thirds of them by 2023. They’re also at the center of political and legal action over abortion. In January, a judge let three states continue to challenge federal government approvals for how one of the drugs usually involved can be prescribed.

This story has been corrected to show that the surname in the third paragraph should be Carpenter, not Carter.

Mulvihill reported from Cherry Hill, New Jersey. Associated Press reporter Michael Hill in Albany, New York, also contributed.

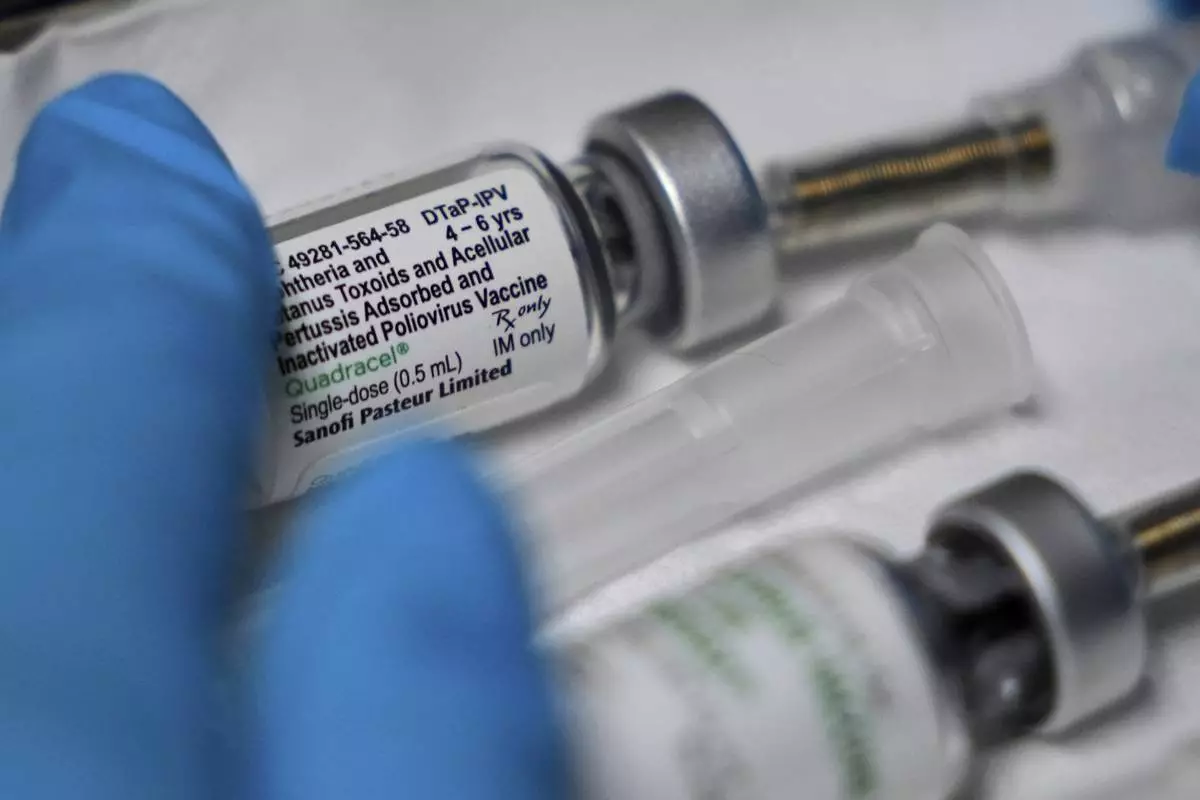

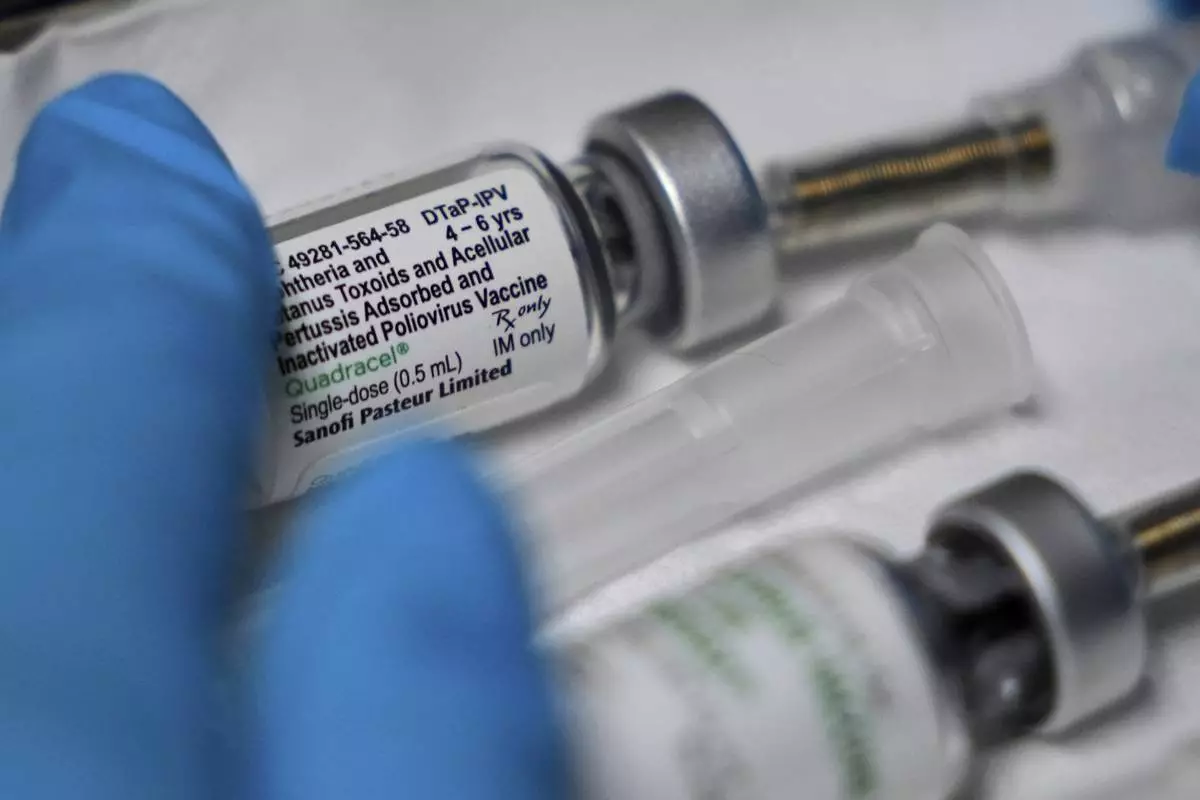

FILE - Mifepristone tablets are seen in a Planned Parenthood clinic Thursday, July 18, 2024, in Ames, Iowa. (AP Photo/Charlie Neibergall, File)

The measles outbreak in West Texas didn’t happen just by chance.

The easily preventable disease, declared eliminated in the U.S. in 2000, ripped through Texas communities in part because health departments were starved of the funding needed to run vaccine programs, officials say.

Nationwide, immunization programs have been left brittle by years of stagnant funding by federal, state and local governments. Health departments got an influx of cash to deal with COVID-19, but it wasn’t enough to make up for years of neglect.

In Texas and elsewhere, this helped set the stage for the measles outbreak and fueled its spread. And now, new federal funding cuts threaten efforts to curb it .

Already, the more than 700 measles cases reported this year in the U.S. have surpassed last year’s total. The vast majority — more than 540 — are in Texas, but cases have popped up in 23 other states. Two Texas children have died.

Here are some takeaways from The Associated Press examination of funding for vaccination programs, how it exacerbates growing vaccine hesitancy and how that fuels outbreaks of infectious disease.

Children in the U.S. are generally required to be vaccinated to go to school, which in the past ensured vaccination rates stayed high enough to prevent infectious diseases like measles from spreading. But a growing number of parents have been skipping the shots for their kids. The share of children exempted from vaccine requirements has reached an all-time high, and just 92.7% of kindergartners got their required shots in 2023. That’s well below the 95% coverage level that keeps diseases at bay.

Though the outbreak in Texas started in Mennonite communities that have been resistant to vaccines and distrustful of government intervention, it quickly jumped to other places with low vaccination rates. There are similar under-vaccinated pockets across the country that could provide the tinder that sparks another outbreak.

Keeping vaccination rates high requires vigilance, commitment and money.

U.S. immunization programs are funded by a variable mix of federal, state and local money. Without enough money, health departments struggle.

Lubbock, about a 90-minute drive from the outbreak’s epicenter, receives a $254,000 immunization grant from the state annually that can be used for staff, outreach, advertising, education and other elements of a vaccine program. That hasn’t increased in at least 15 years.

It used to be enough for three nurses, an administrative assistant, advertising and even goodies to give out at health fairs, said Katherine Wells, the health director. “Now it covers a nurse, a quarter of a nurse, a little bit of an admin assistant, and basically nothing else.”

Other local health departments have seen the same trend. Some, such as Andrews County, have shored up programs with local money. But others haven’t.

Overall, Texas has among the lowest per capita state funding for public health in the nation, just $17 per person in 2023, according to the State Health Access Data Assistance Center.

The health departments millions of Americans depend on for their shots largely rely on two federal programs: Vaccines for Children and Section 317 of the Public Health Services Act. Vaccines for Children mostly provides the actual vaccines. Section 317 provides grants for vaccines but also to run programs and get shots into arms.

Health departments generally use the programs in tandem, and since the pandemic they’ve often been allowed to supplement it with COVID-19 funds.

The 317 funds have been flat for years, even as costs of everything from salaries to vaccines went up. A 2023 CDC report to Congress estimated $1.6 billion was needed to fully fund a comprehensive 317 vaccine program. Last year, Congress approved less than half that: $682 million.

This, along with insufficient state and local funding, forces hard choices, officials and advocates said. Rural clinics may have to be closed, evening and weekend hours eliminated and efforts to fight vaccine mistrust curtailed.

In March, the Trump administration pulled billions of dollars in COVID-19 related funding for state and local health departments — $2 billion of it slated for immunization programs for various diseases. They said it was cut because the pandemic was over, but the federal government had allowed it to be used to shore up public health infrastructure generally, including immunization programs.

After 23 states sued, a judge put a hold on the cuts for now in those states but not in Texas or other states that didn’t join the lawsuit.

Meanwhile, local health departments are not taking chances and are moving to cut services. Details are starting to trickle out.

For example, Dallas County, 350 miles from where the outbreak began, had to cancel more than 50 immunization clinics, said Dr. Philip Huang, the county’s health director. New Mexico, where the outbreak has spread, lost grants that funded vaccine education. Other states have also been hit.

As the cuts further cripple already struggling health departments, alongside increasingly prominent and powerful anti-vaccine voices, doctors worry that vaccine hesitancy will keep spreading. And measles and other viruses will too.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

FILE - Covenant Children's Hospital is pictured from outside the emergency entrance on Wednesday, Feb. 26, 2025, in Lubbock, Texas, after the first U.S. death from measles since 2015. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon, File)

FILE - Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., right, arrives at Reinlander Mennonite Church in Seminole, Texas, on Sunday, April 6, 2025, after a second measles-related death in the state. (AP Photo/Annie Rice, File)

Cesar Acevedo, left, holds his infant son, Adriel Acevedo, as as nurse Tracey McElroy, right, prepares to give him a vaccination that included a polio dose at the Dallas County Health and Human Services immunization clinic in Dallas, Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/LM Otero)

Health department staff members enter the Andrews County Health Department measles clinic carrying doses of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine, Tuesday, April 8, 2025, in Andrews, Texas. (AP Photo/Annie Rice)

A vaccination that includes a polio dose is prepared for a child at the Dallas County Health and Human Services immunization clinic in Dallas, Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/LM Otero)