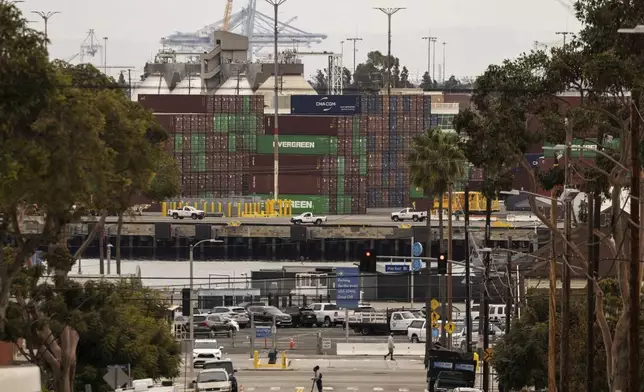

LOS ANGELES (AP) — On a gray March afternoon at the Port of Los Angeles, the largest in the U.S., powerful electric top-handlers whir, beep and grind as they motor back and forth, grabbing trailers from truck beds and stacking them as they move on or off the mighty container ships that ferry goods across the Pacific. Some of the ships, rather than burning diesel to sustain operations as they sit in harbor, plug into electricity instead.

The shift to electricity is part of efforts to clean up the air around America's ports, which have long struggled with pollution that chokes nearby neighborhoods and jeopardizes the health of people living there. The landmark climate law championed by former President Joe Biden earmarked $3 billion to boost those efforts.

Some of the people who live near U.S. hubs now worry that President Donald Trump's administration could seek to cancel or claw back some of that money.

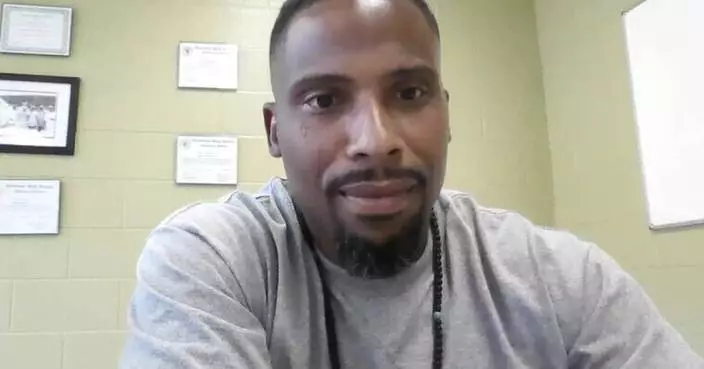

“Our area is disproportionately affected by pollution directly related to the ports activity,” said Theral Golden, who’s lived in the West Long Beach area for more than 50 years. He pointed to the rivers of trucks moving back and forth on nearby highways and overpasses. “It’s all part of the same goods movement effort, and it has to be cleaned up.”

The Biden money aims to slash 3 million metric tons of carbon pollution across 55 ports in more than two dozen states, through cleaner equipment and vehicles, plus infrastructure and community engagement resources.

Some ports say they have already spent hundreds of millions to replace older, dirtier equipment. Members of the American Association of Port Authorities, representing more than 130 public port authorities in the U.S. and beyond, are planning at least $50 billion more of decarbonization projects. Many are easy: for example, drayage trucks — which drive short distances between ports and nearby warehouses — are good candidates for electrification since they don't have to go far between charges.

The Biden money wasn’t enough to completely solve the problem — project requests alone topped $8 billion, per the Environmental Protection Agency — but it was a substantial investment that many experts, including Sue Gander, a director at the research nonprofit World Resources Institute, said would “have a real impact.” They also said it was the biggest outlay of federal funding they'd seen toward the problem.

But Trump, from his first day back in the White House, has attacked much of his predecessor’s climate policies in the name of “energy dominance”. He's sought to roll back clean energy, air, water and environmental justice policies and frozen federal funding, disrupting community organizations and groups planning on the funds for everything from new solar projects to electric school buses to other programs.

EPA spokesperson Shayla Powell said the agency has worked to enable payment accounts for infrastructure law and Inflation Reduction Act grant recipients, “so funding is now accessible.”

While one port said the program was set to be active, others were waiting for the federal grant funding review process to be completed or were monitoring the situation.

The nation’s 300 public and private shipping ports have been centers of pollution for decades. There, the goods Americans want — from cars to building materials to orange juice — are moved by mostly diesel-fueled cranes, trucks and locomotives that emit planet-warming carbon dioxide and cancerous toxins that contribute to heart disease, asthma and shorter life spans. In addition to thousands of longshoremen, truckers and other workers, port operations affect some 31 million Americans living nearby, according to the EPA, often in largely Black, Latino and low-income communities.

Some ports have managed to get a little cleaner through state regulation, diesel pollution reduction efforts, international maritime requirements to cut emissions, and private investment. In voluntary emissions reporting, hubs including the Ports of Los Angeles, Long Beach and New York and New Jersey say some aspects of their operations have significantly improved over the past two decades.

But by many of the ports’ own accounts, they are still releasing tons of sulfur oxides, particulate matters, nitrogen oxides and more. Certain emissions have grown.

Independent groups confirm this. The South Coast Air Quality Management District — a regulatory agency for parts of the Los Angeles region — said that while San Pedro emissions have dropped with more reduction efforts, that pace has slowed. The ports still contribute significantly to local emissions.

“Communities nearby are still going to be vulnerable," said Houston resident Erandi Treviño, cofounder of outreach group the Raíces Collab Project. Local advocates and frontline groups like hers think Trump's attack on pollution regulation will harm further efforts.

Treviño takes several medications and uses an inhaler to manage fatigue, stomachaches, headaches and body pain that she blames on pollution from the Port of Houston. The port itself said pollutants dropped from 2013 to 2019, but some emissions from more vessel activity increased. Houston itself has been flagged by the American Lung Association as one of America's dirtiest cities based on ozone and year-round particle pollution, though the ALA didn't detail the sources of pollution.

Ed Avol, a University of Southern California professor emeritus in clinical medicine, said the motivation to clean up air pollution to protect human and environmental health is clear. But the “whipsaw back-and-forth of the current administration's decision-making process” makes it hard to move forward, he said.

“In the previous administration, billions of dollars were provided to work towards zero air emissions," he said. "In the current Trump administration, the clear intent seems to be to move away from electrification. And that will mean for the millions of people that live around the ports and downwind of the ports, poor air quality, more health effects.”

Despite being major contributors to U.S. economic activity, ports say they are financially stretched by pressure to automate operations and by contentious labor issues.

And moving to electric equipment or vehicles “might not be the best option,” said ports association government relations director Ian Gansler. Electric equipment is more expensive than diesel-fueled, ports might need more of it due to charging time requirements and it might take up more room in a port.

Meanwhile, upgrading electrical service at a port could cost more than $20 million per berth, and some ports have dozens of berths. Ports, too, have to work with utilities to make sure they have enough power.

All this comes as imports have grown. Freight activity could rise 50% by 2050. according to the U.S. Department of Transportation.

Meanwhile, multiple agencies govern, operate in and regulate ports, said Fern Uennatornwaranggoon, climate campaign director for ports at environmental organization Pacific Environment, making it difficult to track “how many pieces of equipment are still diesel, how many pieces have been transitioned, how many more we need to go.”

Alexa St. John is an Associated Press climate reporter. Follow her on X: @alexa_stjohn. Reach her at ast.john@ap.org.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

A commercial ship is visible off the shore in front of Long Beach, Calif., Monday, March 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Etienne Laurent)

A woman reads a book sitting on a column in Hilltop Park overlooking the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles, Monday, March 10, 2025, in Signal Hill, Calif. (AP Photo/Etienne Laurent)

Pollution rises from a ship cruising by the Port of Long Beach where tankers and container ships enter and exit, Monday, March 10, 2025, in San Pedro, Calif. (AP Photo/Etienne Laurent)

An electric top-handler is charging at a station at the Yusen Terminal in the Port of Los Angeles, Tuesday, March 11, 2025, in San Pedro, Calif. (AP Photo/Etienne Laurent)

A ship is loaded with containers in the Port of Los Angeles, Monday, March 10, 2025, in San Pedro, Calif. (AP Photo/Etienne Laurent)

A top-handler drives in the Yusen Terminal at the Port of Los Angeles, Tuesday, March 11, 2025, in San Pedro, Calif. (AP Photo/Etienne Laurent)

A cargo ship is plugged in to an electric grid rather than burning diesel while docked at the Yusen Terminal at the Port of Los Angeles, Tuesday, March 11, 2025, in San Pedro, Calif. (AP Photo/Etienne Laurent)

A cargo ship is plugged in to an electric grid rather than burning diesel at the Yusen Terminal in the Port of Los Angeles, Tuesday, March 11, 2025, in San Pedro, Calif. (AP Photo/Etienne Laurent)

A container is lifted at the Yusen Terminal in the Port of Los Angeles, Tuesday, March 11, 2025, in San Pedro, Calif. (AP Photo/Etienne Laurent)

A container ship is docked in the Port of Los Angeles, Monday, March 10, 2025, in San Pedro, Calif. (AP Photo/Etienne Laurent)

A layer of smog lingers over the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles on Monday, March 10, 2025, as seen from Signal Hill, Calif. (AP Photo/Etienne Laurent)

A picture shot from a bridge overlooking the 710 highway shows the traffic going in and out of the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach, Monday, March 10, 2025, in Long Beach, Calif. (AP Photo/Etienne Laurent)

Theral Golden, who's lived in the West Long Beach area for more than 50 years, poses at Hilltop Park overlooking the Ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles, Monday, March 10, 2025, in Signal Hill, Calif. (AP Photo/Etienne Laurent)

A person on a scooter crosses a street in a residential area located right next to the Port of Los Angeles, Tuesday, March 11, 2025, in San Pedro, Calif. (AP Photo/Etienne Laurent)