NEW YORK (AP) — U.S. births rose slightly last year, but experts don't see it as evidence of reversing a long-term decline.

A little over 3.6 million births were reported for 2024, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention preliminary data. That's 22,250 more than the final tally of 2023 U.S. births, which was released Tuesday.

The 2024 total is likely to grow at least a little when the numbers are finalized, but another set of preliminary data shows overall birth rates rose only for one group of people: Hispanic women.

The rise — less than 1% — may just be a small fluctuation in the middle of a broader trend, said Hans-Peter Kohler, a University of Pennsylvania sociologist who studies family demographics.

“I’d be hesitant to read much into the 2023-24 increase, and certainly not as an indication of a reversal of the trend towards lower or declining U.S. fertility,” Kohler said, adding that more analysis is needed to understand any changes that happened in birth patterns last year.

U.S. births and birth rates have been falling for years. They dropped most years after the 2008-09 recession, aside from a 2014 uptick. They also dropped in 2020, the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, then rose for two straight years after that, an increase experts partly attributed to pregnancies put off amid the pandemic.

A 2% drop in 2023 put U.S. births at fewer than 3.6 million, the lowest one-year tally since 1979. Vermont had the lowest birth rate that year, and Utah had the highest, according to Tuesday's 86-page report on 2023 birth data.

The report, based on a review of all the birth certificates filed that year, shows the average age of mothers at first birth has continued to rise, hitting 27 1/2 years. It was 21 1/2 in the early 1970s, before beginning a steady climb.

Birth rates have long been falling for teenagers and younger women, but were rising for women in their 30s and 40s — a reflection of women pursuing education and careers before trying to start families, experts say. But in 2023, birth rates fell for women in almost all age groups, include women in their early 40s.

Preliminary birth rate data for 2024 shows a continued decrease among teenagers and women in their early 20s. But it also showed increases for women in their late 20s, due entirely to a rise in births to Hispanic women. Increases also were seen for women in their 30s, due to rises among Hispanic and white women, and those in their 40s, due to rises among white women.

Immigrant moms likely drove the increase in Hispanic births, and a solid economy in 2024 also may have helped buoy the numbers, said Dr. John Santelli, a Columbia University expert on family health.

“But I think the changes are small. ... I don’t think it's going to change the long-term trajectories," Santelli said.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

FILE - A pregnant woman stands for a portrait in Dallas, Thursday, May 18, 2023. (AP Photo/LM Otero, File)

BREMEN, Maine (AP) — Commercial fishermen and seafood processors and distributors looking to switch to new, lower-carbon emission systems say the federal funding they relied on for this work is either frozen or unavailable due to significant budget cuts promoted by President Donald Trump’s Department of Government Efficiency.

The changes are designed to replace old diesel-burning engines and outdated at-sea cooling systems and are touted by environmentalists as a way to reduce seafood's carbon footprint. Salmon harvesters in Washington state, scallop distributors in Maine and halibut fishermen in Alaska are among those who told The Associated Press their federal commitments for projects like new boat engines and refrigeration systems have been rescinded or are under review.

“The uncertainty. This is not a business-friendly environment,” said Togue Brawn, a Maine seafood distributor who said she is out tens of thousands of dollars. “If they want to make America great again, then honor your word and tell people what's going on."

Decarbonization of the fishing fleet has been a target of environmental activists in recent years. One study published in the Marine Policy journal states that more than 200 million tons of carbon dioxide were released via fishing in 2016.

That is far less than agriculture, but still a significant piece of the worldwide emissions puzzle. With Earth experiencing worsening storms and its hottest year on record in 2024, reducing the burning of fossil fuels across different industry sectors is critical to fighting climate change, scientists have said.

But climate-friendly projects often cost tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars, leading fishermen to seek U.S. Department of Agriculture or Environmental Protection Agency funds to cover some costs. DOGE, a commission assembled to cut federal spending, has targeted both agencies for cutbacks.

That has left fishermen like Robert Buchmayr of Seattle on the hook for huge bills. Buchmayr said he is nearing completion of a refrigeration project for a salmon boat and was counting on a $45,000 USDA grant to pay for a chunk of it. The agency told him last month the funding is on hold until further notice, he said.

“I'm scrambling, where does the money come from. I was counting on the grant,” Buchmayr said. “I was under the impression that if you got a grant from the United States, it was a commitment. Nothing in the letter was saying, 'Yes, we'll guarantee you the funds depending on who is elected.'”

The full extent of the cuts is unclear, and fishermen affected by them described the situation as chaotic and confusing.

Representatives for the USDA and EPA did not respond to requests for comment from AP about the value of the cuts and whether they were permanent. Dan Smith, USDA Rural Development's state energy director for Alaska, said updates about some grants could arrive in April.

Numerous fishermen, commercial fishing groups and advocates for working waterfronts told AP they learned about the changed status of their grant money in February and March. Some were told the money would not be coming and others were told the funds were frozen while they were subject to a review.

Many prospective grant recipients said they have had difficulty getting updates from the agencies. The lack of certainty has fishermen worried and seeking answers, said Sarah Schumann, a Rhode Island fisherman and director of the Fishery Friendly Climate Action Campaign, a fishermen-led network that works on climate issues.

“They've started contacting me in the last couple of weeks because they've had the plug pulled on money that was already committed,” Schumann said. “If they miss a season they could go out of business.”

In Homer, Alaska, Lacey Velsko of Kaia Fisheries was excited for her decarbonization project, which she said hinged on hundreds of thousands of dollars via a USDA grant to improve a refrigeration system on one of her boats. The recently completed project burns less fuel and yields a higher quality project for the company, which fishes for halibut, Pacific cod and other fish, she said.

But, now the company is told the money is unavailable, leaving a huge cost to bear, Velsko said.

“Of course we think it was unfair that we signed a contract and were told we would be funded and now we’re not funded. If six months down the road we’re still not funded I don’t know what avenue to take,” she said.

The funding cuts have also hurt seafood processors and distributors, such as Brawn in Bremen, Maine. Brawn said she received a little more than half a USDA grant of about $350,000 before learning the rest might not arrive.

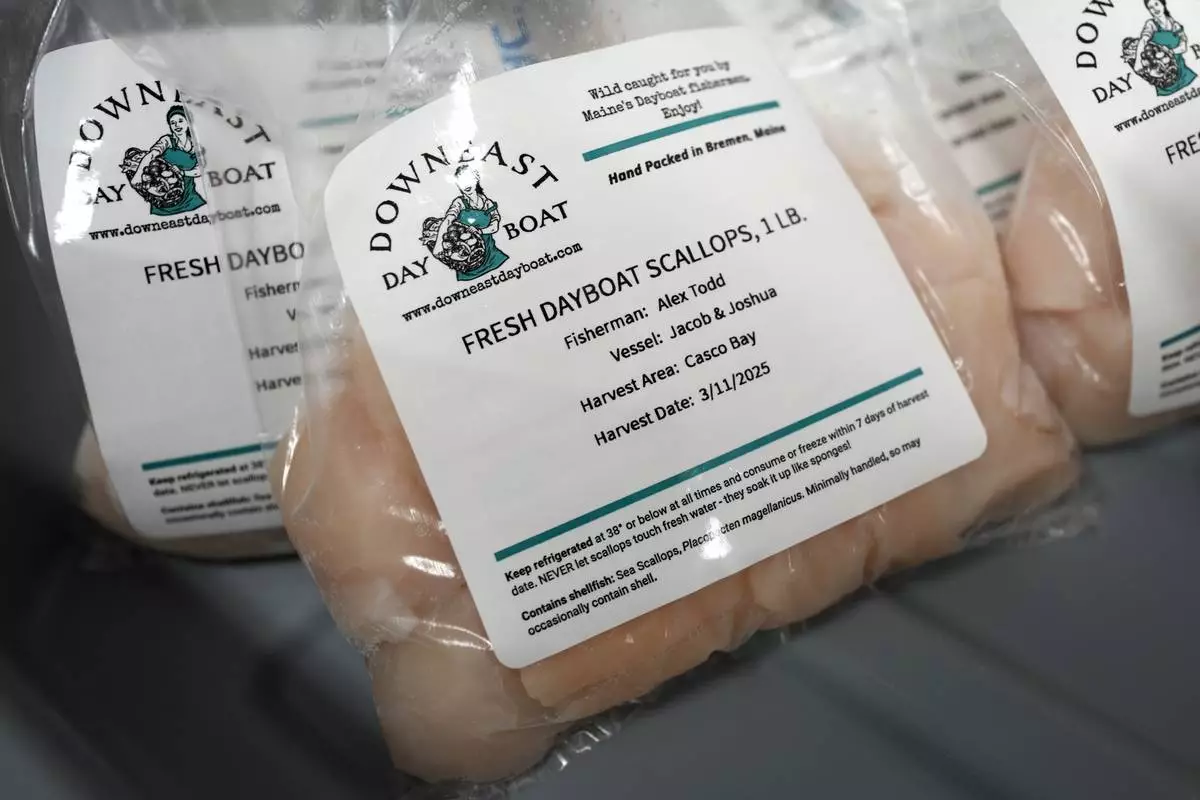

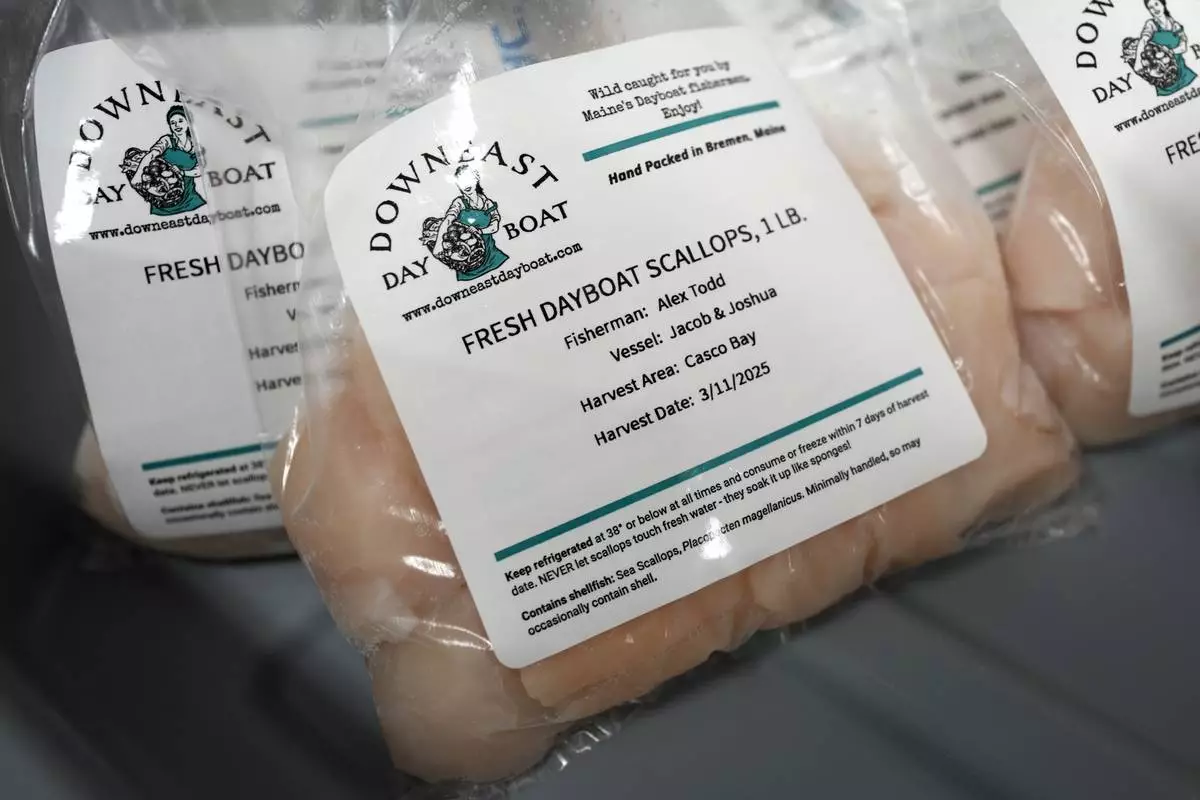

Brawn received the grant for Dayboat Blue, a project that uses a membership-based model to get Maine seafood to nationwide customers while reducing the carbon footprint of transportation and packaging.

“This model can really help fishermen, it can help consumers, it can help communities,” Brawn said. “What it's going to do is it's going to stop the program.”

The confusion on the waterfront is another example of the bumpy rollout of government cutbacks under Trump. The Trump administration halted its firings of hundreds of federal employees who worked on nuclear weapons programs last month. It also moved to rehire medical device, food safety and other workers lost to mass firings at the Food and Drug Administration. New tariffs on key trading partners have also been chaotic.

In Bellingham, Washington, EPA funding was paused for five engine replacement projects split between three companies, said Dan Tucker, executive director of the Working Waterfront Coalition of Whatcom County. He said the uncertainty about funding has made it difficult for fishermen to move ahead with projects that will ultimately benefit their businesses and the community at large.

“A lot of the small guys are like, 'Well, I really want to help out with climate change but I can't afford it,'” Tucker said.

This story was supported by funding from the Walton Family Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Scallops are processed at a processing facility, Tuesday, March 11, 2025, in Bremen, Maine. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

A bucket of scallops is seen on a dock, Tuesday, March 11, 2025, in Yarmouth, Maine. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

Scallops are vacuum-sealed and ready for freezing at a processing facility, Tuesday, March 11, 2025, in Bremen, Maine. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

Fishing boats are moored for the evening, Tuesday, March 11, 2025, in Bremen, Maine. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

Seafood dealer Rogue Brawn speaks to a reporter at a processing facility, Tuesday, March 11, 2025, in Bremen, Maine. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

Jody Nickels sort scallops at a processing facility, Tuesday, March 11, 2025, in Bremen, Maine. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)

A scallop fishing boat leaves the dock, Tuesday, March 11, 2025, in Yarmouth, Maine. (AP Photo/Robert F. Bukaty)