DAKAR, Senegal (AP) — The presidents of Congo and neighboring Rwanda met Tuesday in Qatar for their first direct talks since Rwanda-backed M23 rebels seized two major cities in mineral-rich eastern Congo earlier this year.

The meeting between Congo’s President Felix Tshisekedi and Rwanda’s President Paul Kagame to discuss the insurgency was mediated by Qatar, the three governments said in a statement. The state-run Qatar News Agency published an image of the two African leaders meeting with Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, the energy-rich nation's ruling emir.

Congo and Rwanda reaffirmed their commitment to an immediate and unconditional ceasefire, but the joint statement offered no specifics on how that ceasefire would be implemented or monitored.

The summit came as a previous attempt to bring Congo’s government and M23 leaders together for ceasefire negotiations failed. The rebels pulled out Monday after the European Union announced sanctions on rebel leaders.

Qatar has hosted peace talks between Afghanistan's Taliban and the United States, Chad and rebel forces and over the ongoing Israel-Hamas war in the Gaza Strip.

A diplomat briefed on the meeting said both Tshisekedi and Kagame had formally requested Qatar’s mediation for the talks, which the diplomat said were informal and aimed at building trust rather than resolving all outstanding issues. The diplomat spoke to The Associated Press on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak publicly about the matter.

Peace talks between Congo and Rwanda were unexpectedly canceled in December after Rwanda made the signing of a peace agreement conditional on a direct dialogue between Congo and the M23 rebels, which Congo refused at the time.

The conflict in eastern Congo escalated in January when the Rwanda-backed rebels advanced and seized the strategic city of Goma, followed by Bukavu in February.

M23 is one of about 100 armed groups that have been vying for a foothold in mineral-rich eastern Congo near the border with Rwanda, in a conflict that has created one of the world’s most significant humanitarian crises. More than 7 million people have been displaced.

The rebels are supported by about 4,000 troops from neighboring Rwanda, according to U.N. experts, and at times have vowed to march as far as Congo’s capital, Kinshasa, about 1,600 kilometers (1,000 miles) to the east.

The U.N. Human Rights Council last month launched a commission to investigate atrocities, including allegations of rape and killing akin to “summary executions” by both sides.

FILE - Former members of the Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of Congo (FARDC) and police officers who allegedly surrendered to M23 rebels arrive in Goma, Congo, Sunday, Feb. 23, 2025. (AP Photo/Moses Sawasawa, file)

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Donald Trump signed an executive order Thursday calling for the dismantling of the U.S. Education Department, advancing a campaign promise to take apart an agency that’s been a longtime target of conservatives.

Trump has derided the Education Department as wasteful and polluted by liberal ideology. However, completing its dismantling is most likely impossible without an act of Congress, which created the department in 1979. Republicans said they will introduce legislation to achieve that, while Democrats have quickly lined up to oppose the idea.

The order says the education secretary will, “to the maximum extent appropriate and permitted by law, take all necessary steps to facilitate the closure of the Department of Education and return authority over education to the States and local communities."

It offers no detail on how that work will be carried out or where it will be targeted, though the White House said the agency will retain certain critical functions.

Trump said his administration will close the department beyond its "core necessities," preserving its responsibilities for Title I funding for low-income schools, Pell grants and money for children with disabilities.

The White House said earlier Thursday that the department will continue to manage federal student loans, but the order appears to say the opposite. It says the Education Department doesn't have the staff to oversee its $1.6 trillion loan portfolio and “must return bank functions to an entity equipped to serve America's students.”

At a signing ceremony, Trump blamed the department for America’s lagging academic performance and said states will do a better job.

“It’s doing us no good," he said.

Already, Trump's Republican administration has been gutting the agency. Its workforce is being slashed in half, and there have been deep cuts to the Office for Civil Rights and the Institute of Education Sciences, which gathers data on the nation’s academic progress.

Education Secretary Linda McMahon said she will remove red tape and empower states to decide what’s best for their schools. But she promised to continue essential services and work with states and Congress "to ensure a lawful and orderly transition.”

The measure was celebrated by groups that have long called for an end to the department.

"For decades, it has funneled billions of taxpayer dollars into a failing system—one that prioritizes leftist indoctrination over academic excellence, all while student achievement stagnates and America falls further behind," said Kevin Roberts, president of the Heritage Foundation.

Advocates for public schools said eliminating the department would leave children behind in an American education system that is fundamentally unequal.

“This is a dark day for the millions of American children who depend on federal funding for a quality education, including those in poor and rural communities with parents who voted for Trump,” NAACP President Derrick Johnson said.

Opponents are already gearing up for legal challenges, including Democracy Forward, a public interest litigation group. Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y., called the order a “tyrannical power grab” and “one of the most destructive and devastating steps Donald Trump has ever taken.”

Margaret Spelling, who served as education secretary under Republican President George W. Bush, questioned whether whether the department will be able to accomplish its remaining missions, and whether it will ultimately improve schools.

“Will it distract us from the ability to focus urgently on student achievement, or will people be figuring out how to run the train?" she asked.

Spelling said schools have always been run by local and state officials, and rejected the idea that the Education Department and the federal government have been holding them back.

Currently, much of the agency’s work revolves around managing money — both its extensive student loan portfolio and a range of aid programs for colleges and school districts, like school meals and support for homeless students. The agency also is key in overseeing civil rights enforcement.

The Trump administration has not formally spelled out which department functions could be handed off to other departments or eliminated altogether. It hasn't addressed the fate of other department operations, like its support for for technical education and adult learning, grants for rural schools and after-school programs, and a federal work-study program that provides employment to students with financial need.

States and districts already control local schools, including curriculum, but some conservatives have pushed to cut strings attached to federal money and provide it to states as “block grants” to be used at their discretion.

Block granting has raised questions about vital funding sources including Title I, the largest source of federal money to America’s K-12 schools. Families of children with disabilities have despaired over what could come of the federal department's work protecting their rights.

Federal funding makes up a relatively small portion of public school budgets — roughly 14%. The money often supports supplemental programs for vulnerable students, such as the McKinney-Vento program for homeless students or Title I for low-income schools.

Republicans have talked about closing the Education Department for decades, saying it wastes money and inserts the federal government into decisions that should fall to states and schools. The idea has gained popularity recently as conservative parents’ groups demand more authority over their children’s schooling.

In his platform, Trump promised to close the department “and send it back to the states, where it belongs.” Trump has cast the department as a hotbed of “radicals, zealots and Marxists” who overextend their reach through guidance and regulation.

Even as Trump moves to dismantle the department, he has leaned on it to promote elements of his agenda. He has used investigative powers of the Office for Civil Rights and the threat of withdrawing federal education money to target schools and colleges that run afoul of his orders on transgender athletes participating in women's sports, pro-Palestinian activism and diversity programs.

Sen. Patty Murray of Washington, a Democrat on the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, dismissed Trump's claim that he's returning education to the states. She said he is actually “trying to exert ever more control over local schools and dictate what they can and cannot teach.”

Even some of Trump’s allies have questioned his power to close the agency without action from Congress, and there are doubts about its political popularity. The House considered an amendment to close the agency in 2023, but 60 Republicans joined Democrats in opposing it.

This story has been corrected to reflect the name of the group supporting Trump's education initiatives. It is Moms for Liberty, not Moms for Justice.

The Associated Press’ education coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. The AP is solely responsible for all content. Find the AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

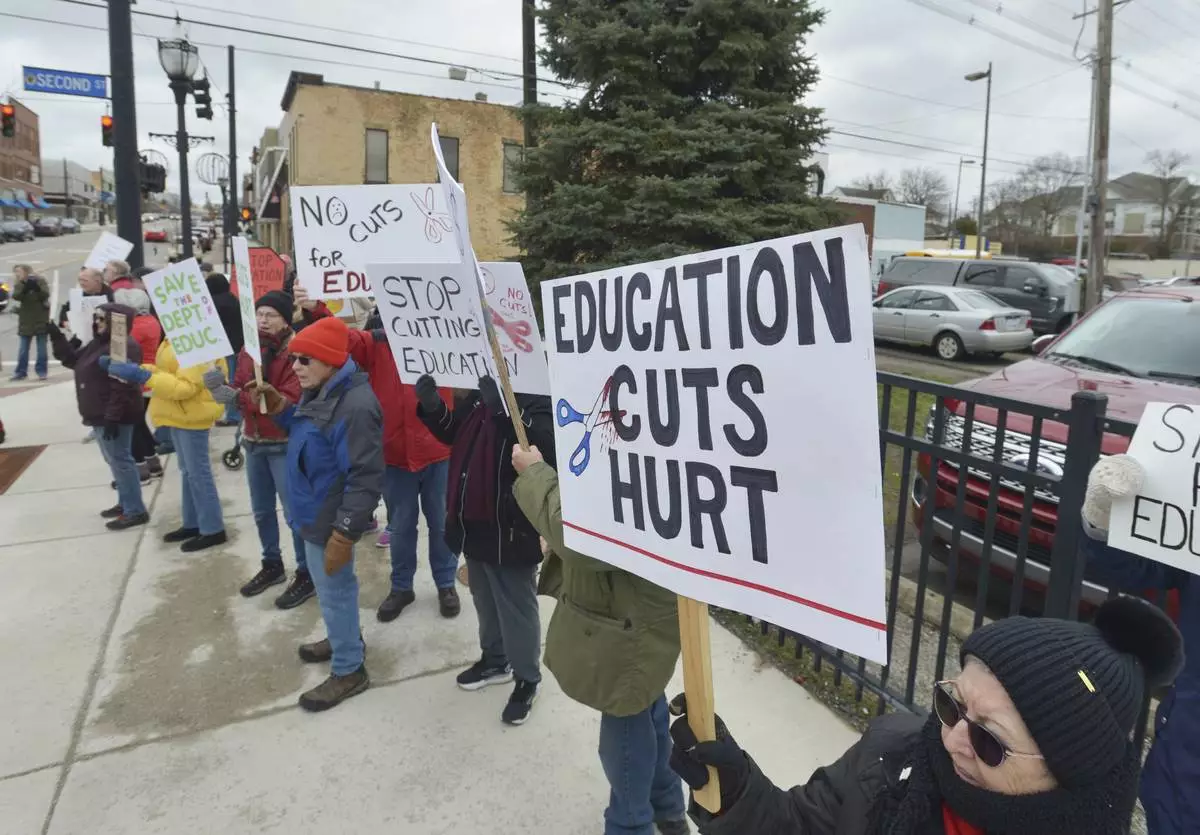

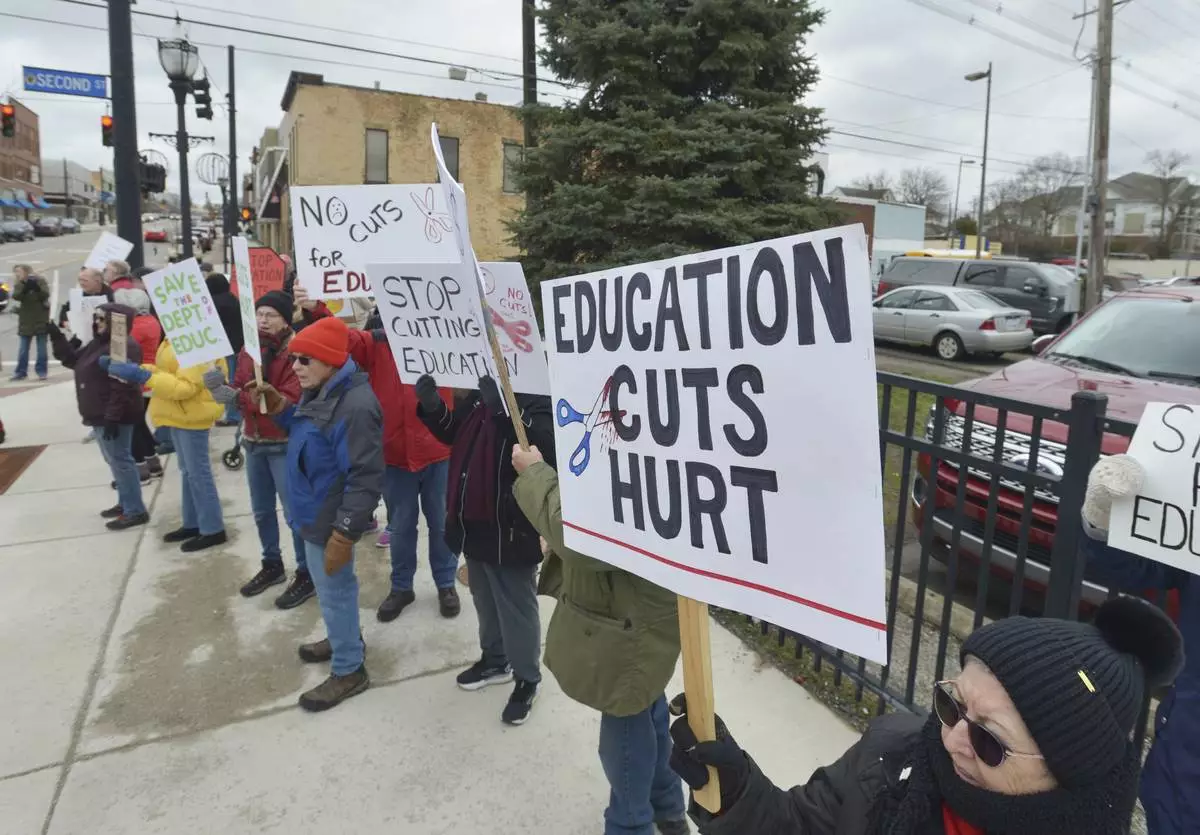

Dozens of people gather in downtown Niles, Mich., Thursday, March 20, 2025, to protest recent government cuts in the Department of Education. (Don Campbell/The Herald-Palladium via AP)

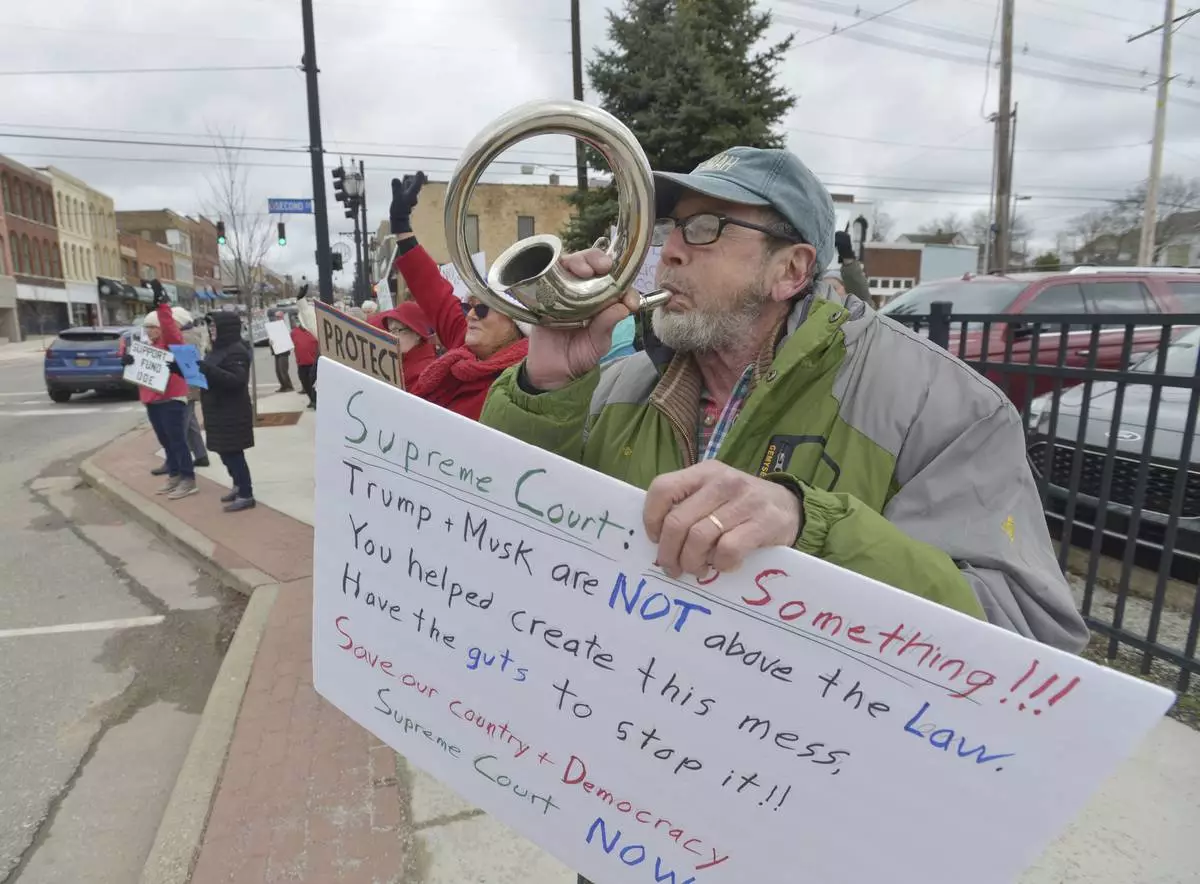

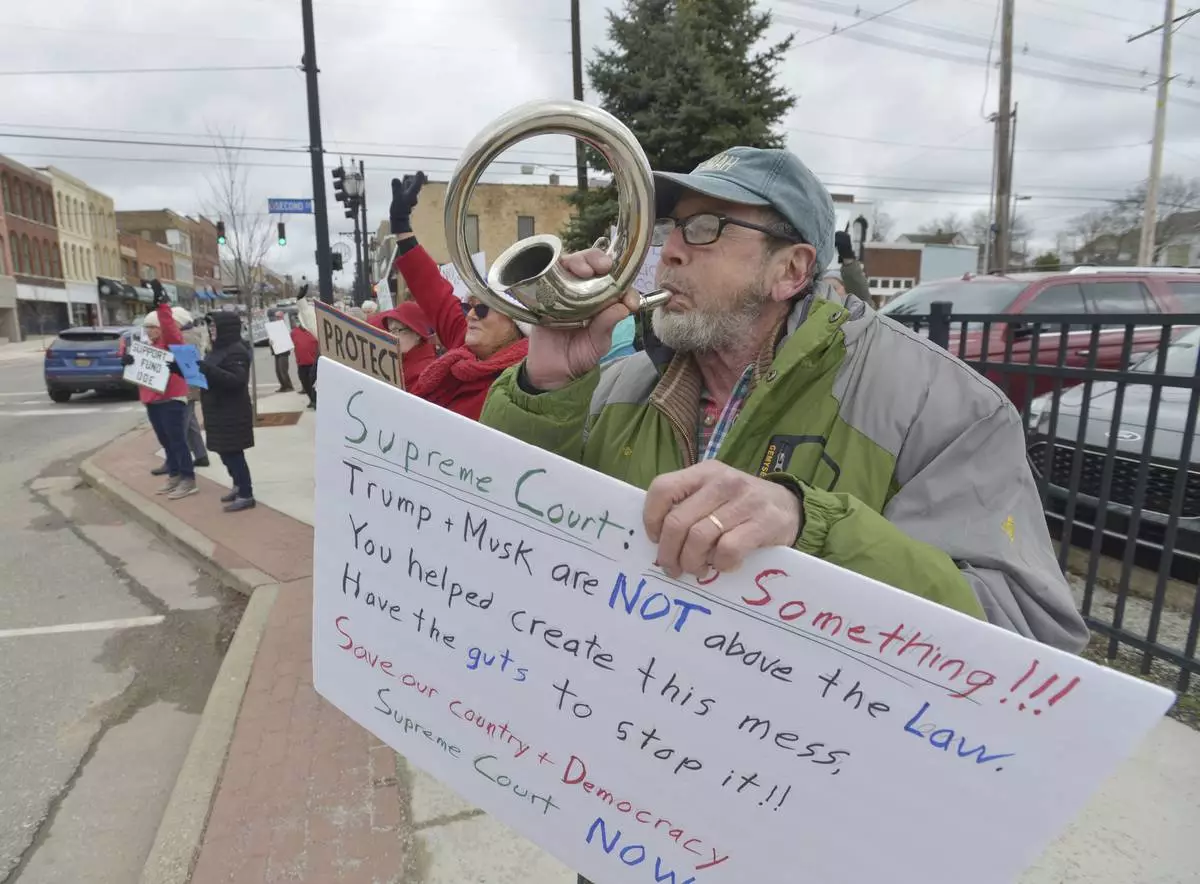

Kay May joins dozens of people gathered in downtown Niles, Mich., Thursday, March 20, 2025, to protest recent government cuts in the Department of Education. (Don Campbell/The Herald-Palladium via AP)

Dozens of people gather in downtown Niles, Mich., Thursday, March 20, 2025, to protest recent government cuts in the Department of Education. (Don Campbell/The Herald-Palladium via AP)

Cindy Mugent joins dozens of people gathered in downtown Niles, Mich., Thursday, March 20, 2025, to protest recent government cuts in the Department of Education. (Don Campbell/The Herald-Palladium via AP)

Bob Blazo blows a horn as he joins dozens of people gathered in downtown Niles, Mich., Thursday, March 20, 2025, to protest recent government cuts in the Department of Education. (Don Campbell/The Herald-Palladium via AP)

President Donald Trump signs an executive order in the East Room of the White House in Washington, Thursday, March 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Ben Curtis)

President Donald Trump arrives at the annual St. Patrick's Day luncheon at the Capitol in Washington, Wednesday, March 12, 2025. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)

President Donald Trump walks with Elon Musk's son X Æ A-Xii on the South Lawn of the White House, Friday, March 14, 2025, in Washington before they depart on Marine One. (AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

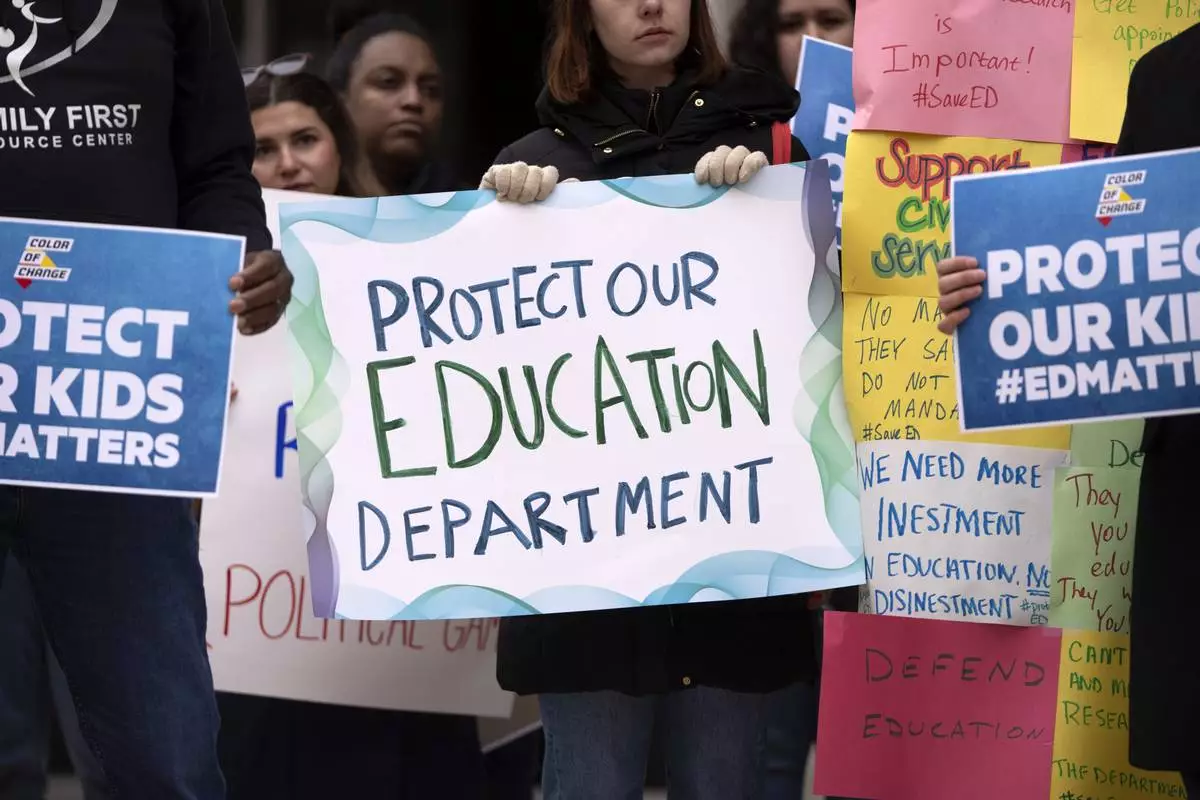

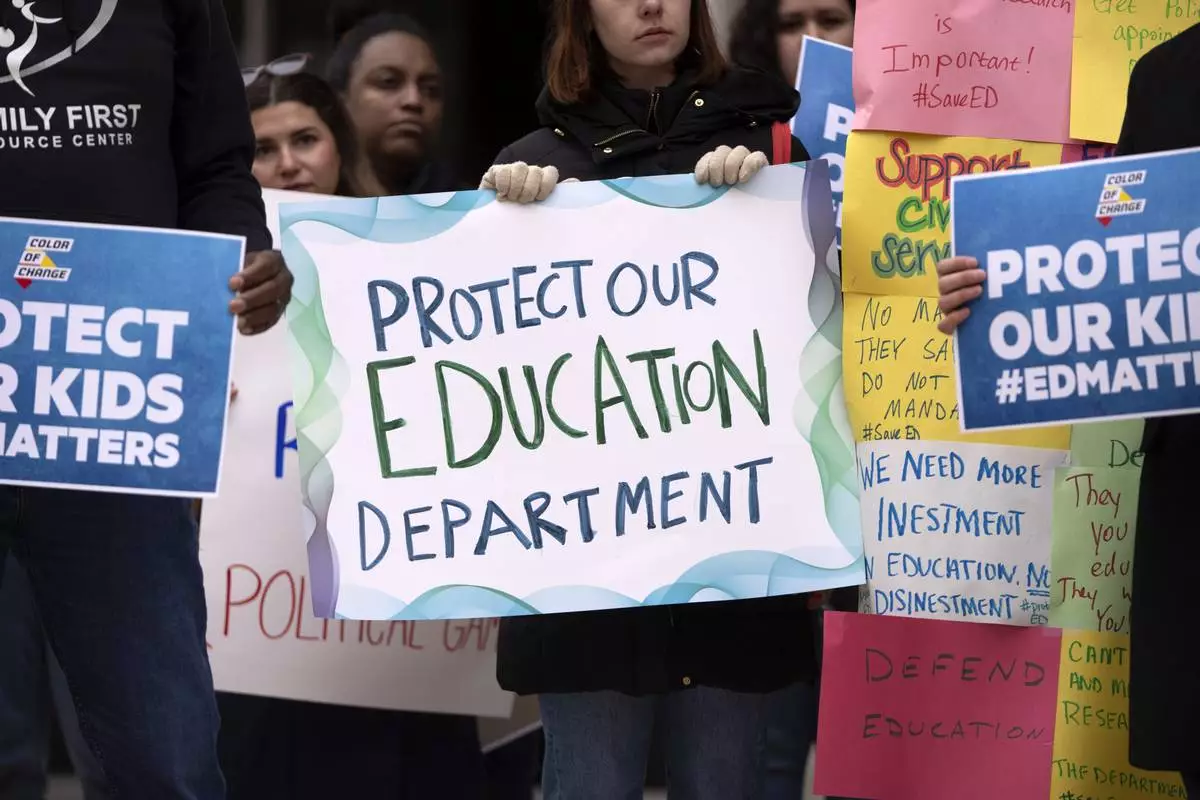

Protestors gather during a demonstration at the headquarters of the Department of Education, Friday, March 14, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

Protestors gather during a demonstration at the headquarters of the Department of Education, Friday, March 14, 2025, in Washington. (AP Photo/Mark Schiefelbein)

Sarah Cummings carries a protest sign to save the Department of Education while joining other protesters outside a Tesla showroom and service center in the North Hollywood section of Los Angeles on Saturday, March 15, 2025. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)