WINDHOEK, Namibia (AP) — Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah was sworn in as Namibia's first female president on Friday, reaching the highest office in her land nearly 60 years after she joined the liberation movement fighting for independence from apartheid South Africa.

The 72-year-old Nandi-Ndaitwah won an election in November to become one of just a handful of female leaders in Africa after the likes of Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of Liberia, Joyce Banda of Malawi and Samia Suluhu Hassan of Tanzania.

Sirleaf and Banda, now former leaders of their countries, and current Tanzania President Hassan all attended Nandi-Ndaitwah's inauguration.

Nandi-Ndaitwah's swearing-in coincided with the 35th anniversary of Namibia's independence, but the ceremony was switched from a soccer stadium where thousands were due to attend to the official presidential office because of heavy rain.

The new president made her pledge to defend, uphold and support the constitution in front of other visiting leaders from South Africa, Zambia, Congo, Botswana, Angola and Kenya.

Nandi-Ndaitwah succeeds Nangolo Mbumba, who had stood in as Namibia's president since February 2024 following the death in office of President Hage Geingob. Nandi-Ndaitwah was promoted to vice president following Geingob's death.

Nandi-Ndaitwah is just the fifth president of Namibia, a sparsely populated nation in southwestern Africa which was a German colony until the end of World War I and then won independence from South Africa in 1990 after decades of struggle and a guerilla war against South African forces that lasted more than 20 years.

“The task facing me as the fifth president of the Republic of Namibia is to preserve the gains of our independence on all fronts and to ensure that the unfinished agenda of economic and social advancement of our people is carried forward with vigor and determination to bring about shared, balanced prosperity for all,” Nandi-Ndaitwah said.

Nandi-Ndaitwah is a veteran of the South West Africa People's Organization, or SWAPO, which led Namibia's fight for independence and has been its ruling party ever since.

She was the ninth of 13 children, her father was an Anglican clergyman, and she attended a mission school that she also later taught in. She joined SWAPO as a teenager in the 1960s and spent time in exile in Zambia, Tanzania, the former Soviet Union and the United Kingdom in the 1970s and 1980s.

She had been a lawmaker in Namibia since 1990 and was the foreign minister before being appointed vice president.

She said she would insist on good governance and high ethical standards in public institutions and would promote closer regional cooperation. She pledged to continue calling for the rights of Palestinians and the people of Western Sahara to self-determination and demanded the lifting of sanctions against Cuba, Venezuela and Zimbabwe.

She also said Namibia would continue to contribute to efforts to fight climate change, a persistent threat for an arid country of just three million people that regularly experiences droughts.

Nandi-Ndaitwah's husband is a retired general who once commanded Namibia's armed forces and was formally given the title “first gentleman.” Nandi-Ndaitwah's inauguration came a day after Namibia's Parliament elected its first female speaker.

FILE - Namibian president elect Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah, of the ruling SWAPO Party, at a news conference in Windhoek, Namibia, Thursday, Dec. 5, 2024 after the election results were made official. (AP Photo/Dirk Heinrich, File)

The measles outbreak in West Texas didn’t happen just by chance.

The easily preventable disease, declared eliminated in the U.S. in 2000, ripped through Texas communities in part because health departments were starved of the funding needed to run vaccine programs, officials say.

Nationwide, immunization programs have been left brittle by years of stagnant funding by federal, state and local governments. Health departments got an influx of cash to deal with COVID-19, but it wasn’t enough to make up for years of neglect.

In Texas and elsewhere, this helped set the stage for the measles outbreak and fueled its spread. And now, new federal funding cuts threaten efforts to curb it .

Already, the more than 700 measles cases reported this year in the U.S. have surpassed last year’s total. The vast majority — more than 540 — are in Texas, but cases have popped up in 23 other states. Two Texas children have died.

Here are some takeaways from The Associated Press examination of funding for vaccination programs, how it exacerbates growing vaccine hesitancy and how that fuels outbreaks of infectious disease.

Children in the U.S. are generally required to be vaccinated to go to school, which in the past ensured vaccination rates stayed high enough to prevent infectious diseases like measles from spreading. But a growing number of parents have been skipping the shots for their kids. The share of children exempted from vaccine requirements has reached an all-time high, and just 92.7% of kindergartners got their required shots in 2023. That’s well below the 95% coverage level that keeps diseases at bay.

Though the outbreak in Texas started in Mennonite communities that have been resistant to vaccines and distrustful of government intervention, it quickly jumped to other places with low vaccination rates. There are similar under-vaccinated pockets across the country that could provide the tinder that sparks another outbreak.

Keeping vaccination rates high requires vigilance, commitment and money.

U.S. immunization programs are funded by a variable mix of federal, state and local money. Without enough money, health departments struggle.

Lubbock, about a 90-minute drive from the outbreak’s epicenter, receives a $254,000 immunization grant from the state annually that can be used for staff, outreach, advertising, education and other elements of a vaccine program. That hasn’t increased in at least 15 years.

It used to be enough for three nurses, an administrative assistant, advertising and even goodies to give out at health fairs, said Katherine Wells, the health director. “Now it covers a nurse, a quarter of a nurse, a little bit of an admin assistant, and basically nothing else.”

Other local health departments have seen the same trend. Some, such as Andrews County, have shored up programs with local money. But others haven’t.

Overall, Texas has among the lowest per capita state funding for public health in the nation, just $17 per person in 2023, according to the State Health Access Data Assistance Center.

The health departments millions of Americans depend on for their shots largely rely on two federal programs: Vaccines for Children and Section 317 of the Public Health Services Act. Vaccines for Children mostly provides the actual vaccines. Section 317 provides grants for vaccines but also to run programs and get shots into arms.

Health departments generally use the programs in tandem, and since the pandemic they’ve often been allowed to supplement it with COVID-19 funds.

The 317 funds have been flat for years, even as costs of everything from salaries to vaccines went up. A 2023 CDC report to Congress estimated $1.6 billion was needed to fully fund a comprehensive 317 vaccine program. Last year, Congress approved less than half that: $682 million.

This, along with insufficient state and local funding, forces hard choices, officials and advocates said. Rural clinics may have to be closed, evening and weekend hours eliminated and efforts to fight vaccine mistrust curtailed.

In March, the Trump administration pulled billions of dollars in COVID-19 related funding for state and local health departments — $2 billion of it slated for immunization programs for various diseases. They said it was cut because the pandemic was over, but the federal government had allowed it to be used to shore up public health infrastructure generally, including immunization programs.

After 23 states sued, a judge put a hold on the cuts for now in those states but not in Texas or other states that didn’t join the lawsuit.

Meanwhile, local health departments are not taking chances and are moving to cut services. Details are starting to trickle out.

For example, Dallas County, 350 miles from where the outbreak began, had to cancel more than 50 immunization clinics, said Dr. Philip Huang, the county’s health director. New Mexico, where the outbreak has spread, lost grants that funded vaccine education. Other states have also been hit.

As the cuts further cripple already struggling health departments, alongside increasingly prominent and powerful anti-vaccine voices, doctors worry that vaccine hesitancy will keep spreading. And measles and other viruses will too.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

FILE - Covenant Children's Hospital is pictured from outside the emergency entrance on Wednesday, Feb. 26, 2025, in Lubbock, Texas, after the first U.S. death from measles since 2015. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon, File)

FILE - Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., right, arrives at Reinlander Mennonite Church in Seminole, Texas, on Sunday, April 6, 2025, after a second measles-related death in the state. (AP Photo/Annie Rice, File)

Cesar Acevedo, left, holds his infant son, Adriel Acevedo, as as nurse Tracey McElroy, right, prepares to give him a vaccination that included a polio dose at the Dallas County Health and Human Services immunization clinic in Dallas, Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/LM Otero)

Health department staff members enter the Andrews County Health Department measles clinic carrying doses of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine, Tuesday, April 8, 2025, in Andrews, Texas. (AP Photo/Annie Rice)

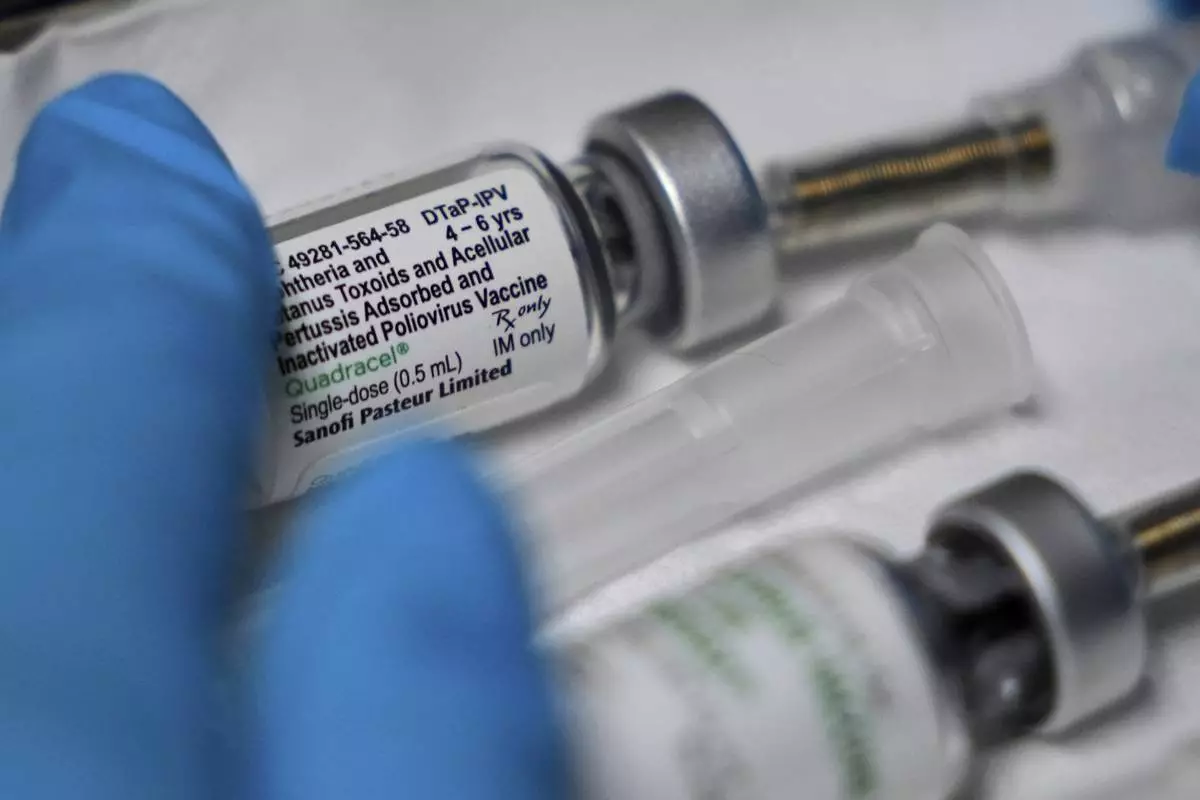

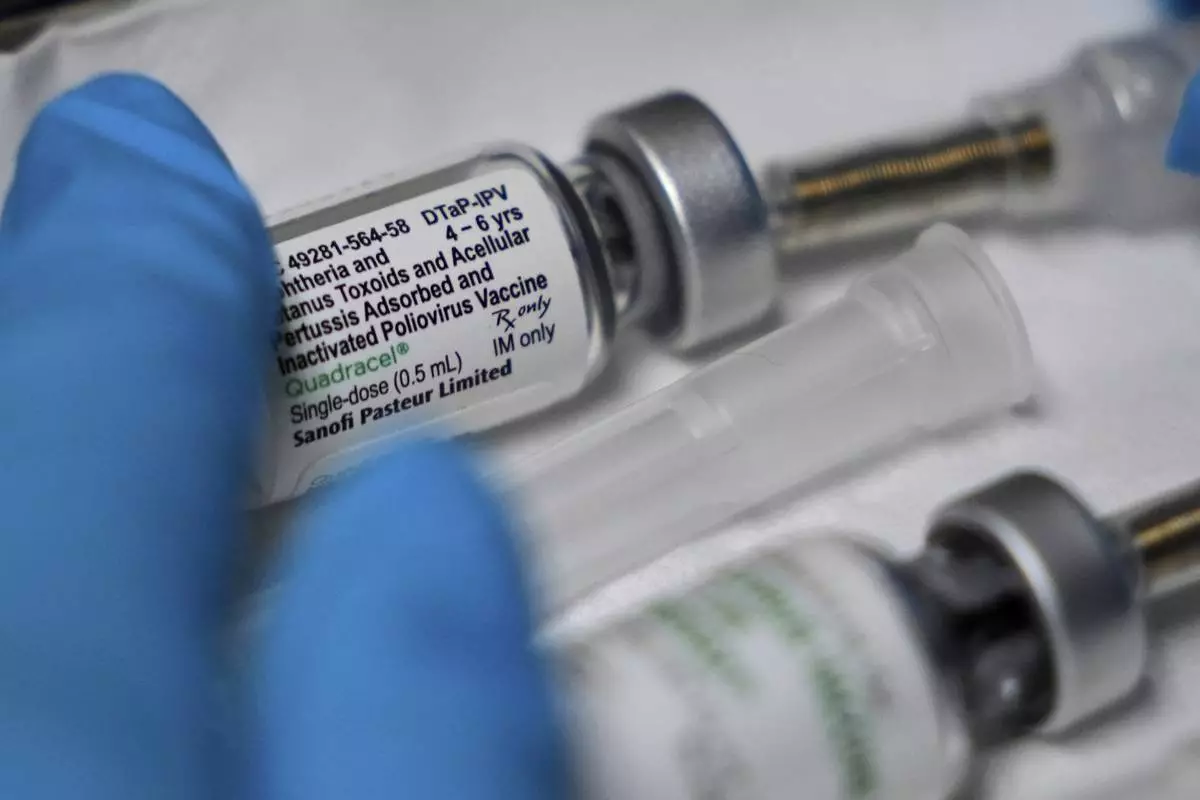

A vaccination that includes a polio dose is prepared for a child at the Dallas County Health and Human Services immunization clinic in Dallas, Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/LM Otero)