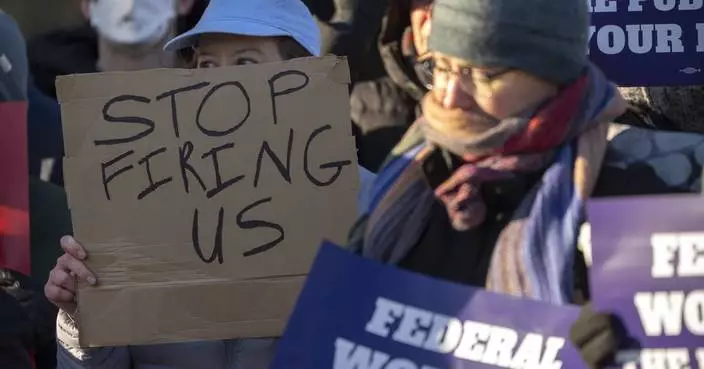

WASHINGTON (AP) — Every day over the past few weeks, the Pentagon has faced questions from angry lawmakers, local leaders and citizens over the removal of military heroes and historic mentions from Defense Department websites and social media pages after it purged online content that promoted women or minorities.

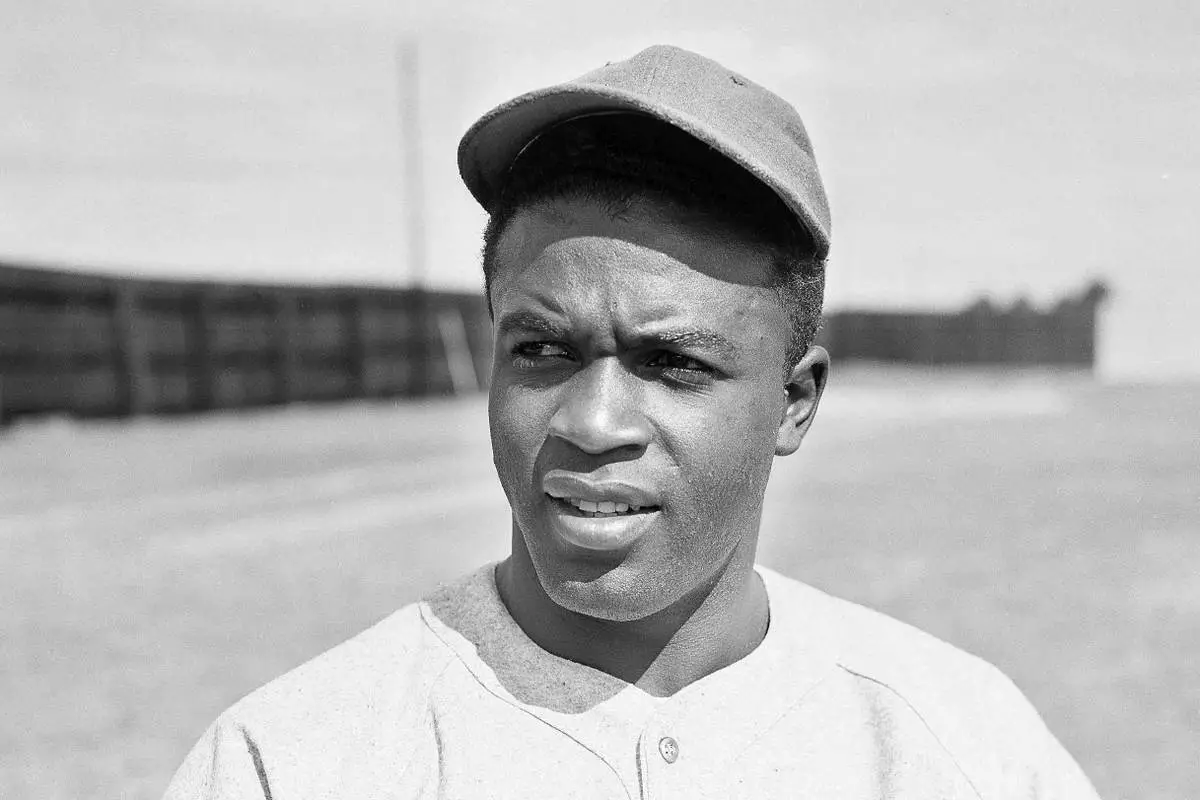

In response, the department has scrambled to restore a handful of those posts as their removals have come to light. While the pages of some well-known veterans, including baseball and civil rights icon Jackie Robinson, are now back up on Pentagon websites, officials warn that many posts tagged for removal in error may be gone forever.

The restoration process has been so hit or miss that even groups that the administration has said are protected, like the Tuskegee Airmen, the first Black military pilots who served in a segregated World War II unit, still have deleted pages that as of Saturday had not been restored.

This past week chief, Pentagon spokesman Sean Parnell said in a video that mistaken removals will be quickly rectified. “History is not DEI,” he said, referring to diversity, equity and inclusion.

But due to the enormous size of the military and the wide range of commands, units and bases, there has been an array of interpretations of what to remove and how as part of the Pentagon directive to delete online content that promotes DEI. Officials from across the military services said they have asked for additional guidance from the Pentagon on what should be restored, but have yet to receive any.

The officials, who spoke to The Associated Press on condition of anonymity to describe internal deliberations, said, for example, they were waiting for guidance on whether military “firsts” count as history that can be restored. The first female Army Reserve graduate of Ranger School, Maj. Lisa Jaster, or the first female fighter pilot, Air Force Maj. Gen. Jeannie Leavitt, both had their stories deleted.

Some officials said their understanding was it did not matter whether it was a historic first. If the first was based on what Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth found to be a disqualifying characteristic, such as gender or race, it had to go, they said.

One Army team has taken a very deliberate approach.

According to the officials, the team took down several major historical heritage sites that had many postings about women and various ethnic or racial groups. They are now going through them all and plan to rework and repost as much as possible on a new website focused on Army heroes. The process, the officials said, could take months.

Overall, tens of thousands of online posts that randomly mention dozens of key words, including “gay,” “bias” and “female” — have been deleted. Officials warn that the bulk of those images are gone for good. Even as complaints roll in, officials will be careful about restoring things unless senior leaders approve.

The officials described the behind-the-scenes process as challenging, frustrating and emotionally draining. Workers going through years of posts to take down mentions of historic accomplishments by women or minorities were at times reduced to tears or lashed out in anger at commanders directing the duty, the officials said.

Others were forced to pull down stories they were proud of and had worked on themselves. They were often confused about the parameters for removal once a key word was found, and they erred on the side of removal, according to the officials.

Not complying fully with the order was seen as dangerous because it could put senior military service leaders at risk of being fired or disciplined if an errant post celebrating diversity was left up and found. Officials said the department relied in large part on a blind approach — using artificial intelligence computer commands to search for dozens of those key words in online department, military and command websites.

If a story or photo depicted or included one of the terms, the computer program then added “DEI” into the web address of the content, which flagged it and led to its removal.

Purging posts from X, Facebook and other social media sites is more complicated and time intensive. An AI command would not work as well on those sites.

So military service members and civilians have evaluated social media posts by hand, working late into the night and on weekends to pore over their unit’s social media pages, cataloging and deleting references going back years. Because some civilians were not allowed to work on weekends, military troops had to be called in to replace them, as the officials described it.

The Defense Department is publicly insisting that mistakes will be corrected.

As an example, the Pentagon on Wednesday restored some pages highlighting the crucial wartime contributions of Navajo Code Talkers and other Native American veterans. That step came days after tribes condemned the removal. Department officials said the Navajo Code Talker material was erroneously erased,

The previous week, pages honoring a Black Medal of Honor winner and Japanese American service members were also restored.

The restorations represent a shift from early, adamant denials that any deletion of things such as the Enola Gay or prominent service members was happening at all. At least two images of the Enola Gay, the plane that dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, Japan, during World War II, are still missing.

“This is fake news and anyone with a pulse knows it!” the Defense Department's new “Rapid Response” social media account asserted March 7. “We are NOT removing images of the Enola Gay or any other pictures that honor the legacy of our warfighters.”

Over time, the Pentagon has shifted its public response as more examples of deleted pages came to light.

On Thursday, Parnell acknowledged in a video posted online that: “Because of the realities of AI tools and other software, some important content was incorrectly pulled off line to be reviewed. We want to be very, very clear: History is not DEI. When content is either mistakenly removed, or if it’s maliciously removed, we continue to work quickly to restore it.”

But others have seen the widespread erasure of history.

“Most female aviator stories and photographs are disappearing—including from the archives. From the WASPs to fighter pilots, @AFThunderbirds to @BlueAngels —they've erased us,” Carey Lohrenz, one of the Navy's first female F-14 Tomcat pilots, posted to X. “It’s an across the board devastating loss of history and information.” Among the webpages removed include one about the Women Air Service Pilots, or WASPs, the female World War II pilots who were vital in ferrying warplanes for the military, and the Air Force Thunderbirds.

Parnell, Hegseth and others have vigorously defended the sweeping purge despite the flaws.

“I think the president and the secretary have been very clear on this — that anybody that says in the Department of Defense that diversity is our strength is, is frankly, incorrect,” Parnell said during a Pentagon media briefing. “Our shared purpose and unity are our strength."

FILE - Baseball Player Jackie Robinson with the Montreal Royals club at Sanford, Fla., March 4, 1946. (AP Photo/Bill Chaplis, File)

FILE - Navajo Code Talker Thomas Begay salutes during the national anthem at the Arizona State Navajo Code Talkers Day celebration, Aug. 14, 2022, in Phoenix. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin, File)

FILE - Maj. Lisa Jaster, center, the first Army Reserve female to graduate the Army's Ranger School, stands in formation with other Rangers during an Army Ranger school graduation ceremony, Oct. 16, 2015, in Fort Benning, Ga. (AP Photo/Branden Camp, File)