JACKSON, N.H. (AP) — A skier since age 4, Thomas Brennick now enjoys regular trips to New Hampshire’s Black Mountain with his two grandchildren.

“It’s back to the old days,” he said from the Summit Double chairlift on a recent sunny Friday. “It's just good, old-time skiing at its best.”

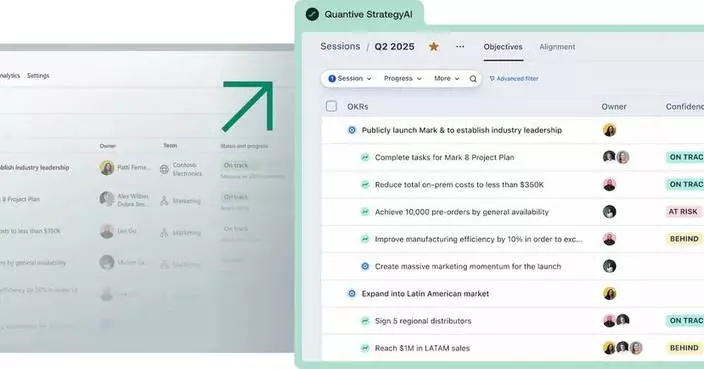

Behind the scenes, the experience is now propelled by a high-tech system designed to increase efficiency at the state’s oldest ski area. And while small, independent resorts can’t compete on infrastructure or buying power with conglomerates like Vail, which owns nearby Attitash Mountain Resort and seven others in the Northeast alone, at least one entrepreneur is betting technology will be “a really great equalizer.”

That businessman is Erik Mogensen, who bought Black Mountain last year and turned it into a lab for his ski mountain consultancy, Entabeni Systems. The company builds systems that put lift tickets sales, lesson reservations and equipment rentals online while collecting detailed data to inform decisions such as where to make more snow and how much.

“A lot of general managers will go out and look at how many rows of cars are parked, and that’s kind of how they tell how busy they are,” Mogensen said. “We really want to look at that transactional data down to the deepest level.”

That includes analyzing everything from the most popular time to sell hot dogs in the lodge to how many runs a season pass holder makes per visit.

“The large operators, they can do a lot of things at scale that we can’t. They can buy 20 snow cats at a time, 10 chairlifts, those types of things. We can’t do that, but we’re really nimble,” Mogensen said. “We can decide to change the way we groom very quickly, or change the way we open trails, or change our (food and beverage) menu in the middle of a day.”

Mogensen, who says his happiest moments are tied to skiing, started Entabeni Systems in 2015, driven by the desire to keep the sport accessible. In 2023, he bought the company Indy Pass, which allows buyers to ski for two days each at 230 independent ski areas, including Black Mountain. It's an alternative to the Epic and Ikon multi-resort passes offered by the Vail and Alterra conglomerates.

Black Mountain was an early participant in Indy Pass. When Mogensen learned it was in danger of closing, he was reminded of his hometown's long-gone ski area. He bought Black Mountain aiming to ultimately transform it into a cooperative.

Many Indy Pass resorts also are clients of Entabeni Systems, including Utah's Beaver Mountain, which bills itself as the longest continuously-run family owned mountain resort in the U.S.

Kristy Seeholzer, whose husband’s grandfather founded Beaver Mountain, said Entabeni streamlined its ticketing and season pass system. That led to new, lower-priced passes for those willing to forgo skiing during holiday weeks or weekends, she said.

“A lot of our season pass holders were self-limiting anyway. They only want to ski weekdays because they don’t want to deal with weekends,” she said. “We could never have kept track of that manually."

Though she is pleased overall, Seeholzer said the software can be challenging and slow.

“There are some really great programs out there, like on the retail side of things or the sales side of things. And one of the things that was a little frustrating was it felt like we were reinventing the wheel,” she said.

Sam Shirley, 25, grew up skiing in New Hampshire and worked as a ski instructor and ski school director in Maine while attending college. But he said increasing technology has drastically changed the way he skis, pushing him to switch mostly to cross-country.

“As a customer, it’s made things more complicated,” he said. "It just becomes an extra hassle.”

Shirley used to enjoy spur-of-the-moment trips around New England, but has been put off by ski areas reserving lower rates for those who buy tickets ahead. He doesn’t like having to provide detailed contact information, sometimes even a photograph, just to get a lift ticket.

It's not just independent ski areas that are focused on technology and data. Many others are using lift tickets and passes embedded with radio frequency identification chips that track skiers' movements.

Vail resorts pings cell phones to better understand how lift lines are forming, which informs staffing decisions, said John Plack, director of communications. Lift wait times have decreased each year for the past three years, with 97% under 10 minutes this year, he said.

“Our company is a wildly data-driven company. We know a lot about our guest set. We know their tastes. We know what they like to ski, we know when they like to ski. And we’re able to use that data to really improve the guest experience,” he said.

That improvement comes at a cost. A one-day lift ticket at Vail's Keystone Resort in Colorado sold for $292 last week. A season pass cost $418, a potentially good deal for diehard skiers, but also a reliable revenue stream guaranteeing Vail a certain amount of income even as ski areas face less snow and shorter winters.

The revenue from such passes, especially the multi-resort Epic Pass, allowed the company to invest $100 million in snowmaking, Plack said.

“By committing to the season ahead of time, that gives us certainty and allows us to reinvest in our resorts," he said.

Mogensen insists bigger isn’t always better, however. Lift tickets at Black Mountain cost $59 to $99 per day and a season's pass is about $450.

“You don’t just come skiing to turn left and right. You come skiing because of the way the hot chocolate tastes and the way the fire pit smells and what spring skiing is and what the beer tastes like and who you’re around,” he said. “Skiing doesn’t have to be a luxury good. It can be a community center.”

Brennick, the Black Mountain lift rider who was skiing with his grandchildren, said he has noticed a difference since the ski area was sold.

“I can see the change,” he said. “They're making a lot of snow and it shows.”

Ramer reported from Concord, New Hampshire.

Skiers and snowboarders ride a lift at Keystone Ski Resort in Keystone, Colo., Thursday, March 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Thomas Peipert)

Skiers and snowboarders ride a lift at Keystone Ski Resort in Keystone, Colo., Thursday, March 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Thomas Peipert)

Skiers and snowboarders ride a lift at Keystone Ski Resort in Keystone, Colo., Thursday, March 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Thomas Peipert)

Skiers and snowboarders make their way down a run at Keystone Ski Resort in Keystone, Colo., Thursday, March 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Thomas Peipert)

A skier makes their way down a mogul run at Keystone Ski Resort in Keystone, Colo., Thursday, March 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Thomas Peipert)

Skiers enjoy their lunch on picnic tables outside the Alpine Cabin, a mid-slope refreshment stop, at Black Mountain, Friday, March 14, 2025, in Jackson, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Skier Bill Eppich, of Hanover, Mass., uses a computer display to order lunch at the Alpine Cabin, a mid-slope refreshment stop, at Black Mountain, Friday, March 14, 2025, in Jackson, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Cars are parked near a lift at the base of the Black Mountain ski area, Friday, March 14, 2025, in Jackson, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Lift attendant Veronica Crespo Jimenez scans a skier's pass, which are embedded with an RFID chip, at Black Mountain, Friday, March 14, 2025, in Jackson, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Empty champagne bottles are displayed at the Alpine Cabin, a mid-slope refreshment stop, as skiers ride the lift to the summit at Black Mountain, Friday, March 14, 2025, in Jackson, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Skiers ride downhill at Black Mountain, Friday, March 14, 2025, in Jackson, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

A digital terminal displays the Black Mountain logo at the lift ticket point of sale location at the base of the mountain, Friday, March 14, 2025, in Jackson, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

A skier wearing shorts heads down a trail as a rider takes a chair lift to the summit at Black Mountain, Friday, March 14, 2025, in Jackson, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Erik Mogensen, right, founder of Entabeni Systems and the general manager of Black Mountain, talks with engineers in a temporary hardware and software technical center at the base of the mountain, Friday, March 14, 2025, in Jackson, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Erik Mogensen, founder of Entabeni Systems and the general manager of Black Mountain, is interviewed slope side at the mountain, Friday, March 14, 2025, in Jackson, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Lift attendant Veronica Crespo Jimenez uses a handheld device to scan a skier's pass, which is embedded with an RFID chip, at Black Mountain, Friday, March 14, 2025, in Jackson, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)

Skiers head down a trail at Black Mountain, Friday, March 14, 2025, in Jackson, N.H. (AP Photo/Charles Krupa)