Erin McGuire spent years cultivating fruits and vegetables like onions, peppers and tomatoes as a scientist and later director of a lab at the University of California-Davis. She collaborated with hundreds of people to breed drought-resistant varieties, develop new ways to cool fresh produce and find ways to make more money for small farmers at home and overseas.

Then the funding stopped. Her lab, and by extension many of its overseas partners, were backed financially by the United States Agency for International Development, which Trump's administration has been dismantling for the past several weeks. Just before it was time to collect data that had been two years in the making, her team received a stop work order. She had to lay off her whole team. Soon she was laid off, too.

“It’s really just been devastating,” she said. “I don’t know how you come back from this.”

The U.S. needs more publicly funded research and development on agriculture to offset the effects of climate change, according to a paper out in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences this month. But instead the U.S. has been investing less. United States Department of Agriculture data shows that as of 2019, the U.S. spent about a third less on agricultural research than its peak in 2002, a difference of about $2 billion. The recent pauses and freezes to funding for research on climate change and international development are only adding to the drop. It’s a serious issue for farmers who depend on new innovations to keep their businesses afloat, the next generation of scientists and eventually for consumers who buy food.

If scientists have reliable backing, they can keep improving crop varieties to better withstand perilous weather conditions like droughts or floods, find new uses for existing crop species, figure out how to protect workers, develop new technology to aid in planting and harvesting or create more effective ways of fighting pests. They can also investigate agriculture’s potential role in fighting climate change.

“This is terrible news for the U.S. agricultural sector,” said Cornell associate professor Ariel Ortiz-Bobea, the lead author of the paper.

As the Trump administration pauses and shutters research programs funded by the Environmental Protection Agency, USDA and other agencies, Ortiz-Bobea and other experts have seen field trials stopped, postdoctoral positions eliminated and a looming gap forming between the reality of climate change and the tools farmers have to deal with it.

The EPA declined to comment, and the USDA and USAID did not respond to Associated Press queries.

Ortiz-Bobea and his team quantified overall U.S. agricultural productivity, estimated how much it would be slowed by climate change in coming years and calculated how much money would need to be invested in research and development to counteract that slowdown.

Think of it like riding a bike into a headwind, Ortiz-Bobea said. To maintain the same speed, you have to pedal harder; in this case, R&D can be that extra push.

Some countries are heading that direction. China spends almost twice as much as the U.S. on agricultural research, and has increased its research investments by five times since 2000, wrote Omanjana Goswami, a scientist with the Food and Environment team at the Union of Concerned Scientists, in an email.

Spending cutbacks have also shuttered agricultural research across almost all of the Feed the Future Innovation Labs, of which McGuire's was one. Those 17 labs across 13 universities focused on food security, technical agriculture research, policy and various aspects of climate change. The stop-work orders at those labs not only disappointed researchers, but made useless much of their work.

“There are many, many millions of dollars of expenditure that will generate nothing now because the work couldn’t be finished,” said David Tschirley, a professor who had been directing another one of those programs, the Innovation Lab for Food Security Policy Research, Capacity and Influence at Michigan State University, since 2019.

Some researchers hope that other sources of funding can fill the gaps: “That’s where private sector could really step up,” said Swati Hegde, a scientist in the Food, Land, and Water Program at the World Resources Institute.

From an agricultural point of view, climate change is “really scary,” with larger and larger regions exposed to temperatures above healthy growing conditions for many crops, said Bill Anderson, CEO of Bayer, a multinational biotechnology and pharmaceutical company that invested nearly $3 billion in agricultural research and development last year. But private companies have their own constraints on R&D investment, and he said Bayer can't invest as much as it would like in that area.

“I don’t think that private industry can replicate" how federal funding typically supports early stage, speculative science, he said, “because the economics don't really work.” He added that industry tends to be better suited to back ideas that have already been validated.

Goswami, of the Union of Concerned Scientists, also expressed concerns that private research funding isn't as trackable and transparent as public funding. And others said even sizeable investments from companies don't give anywhere near enough money to match government funding.

The full impact may not be apparent for many years, and the damage won't easily be repaired. Experts think it will be a blow in other countries where climate change is already decimating yields, driving hunger and conflict.

“I really worry that if we don’t really look at the global food situation, we will have a disaster,” said David Zilberman, a professor at UC Berkeley who won a Wolf Prize in 2019 for his work on agriculture.

But even domestically, experts say one thing is almost certain: this will mean even higher prices at the grocery store now and in the future.

“More people on the Earth, you need more productivity to prevent food prices going crazy,” said Tom Hertel, a professor of agricultural economics at Purdue University. Even if nothing changes right away, he thinks “10 years from now, 20 years from now, our yield growth will surely be stunted” by cuts to research on agricultural productivity.

Many scientists said the wound isn’t just professional but personal.

“People are very demoralized,” especially younger researchers who don’t have tenure and want to work on international food research, said Zilberman.

Now those dreams are on hold for many. In carefully tended research plots, weeds begin to grow.

Follow Melina Walling on X @MelinaWalling and Bluesky @melinawalling.bsky.social.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

FILE - Bill Werner, Lead Greenhouse Manager of the College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences at the University of California, Davis, walks between plants and evaporative cooling pads in a greenhouse at the Core Greenhouse Complex on the campus in Davis, Calif., May 20, 2024. (AP Photo/Jeff Chiu, File)

FILE - A villager tends to his vegetable garden in a plot that is part of a climate-smart agriculture program funded by the United States Agency for International Development in Chipinge, Zimbabwe, Sept. 19, 2024. (AP Photo/Aaron Ufumeli, File)

FILE - Katrina Cornish, a professor at Ohio State University who studies rubber alternatives, harvests rubber dandelion seeds inside a greenhouse, Feb. 6, 2024, in Wooster, Ohio. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel, File)

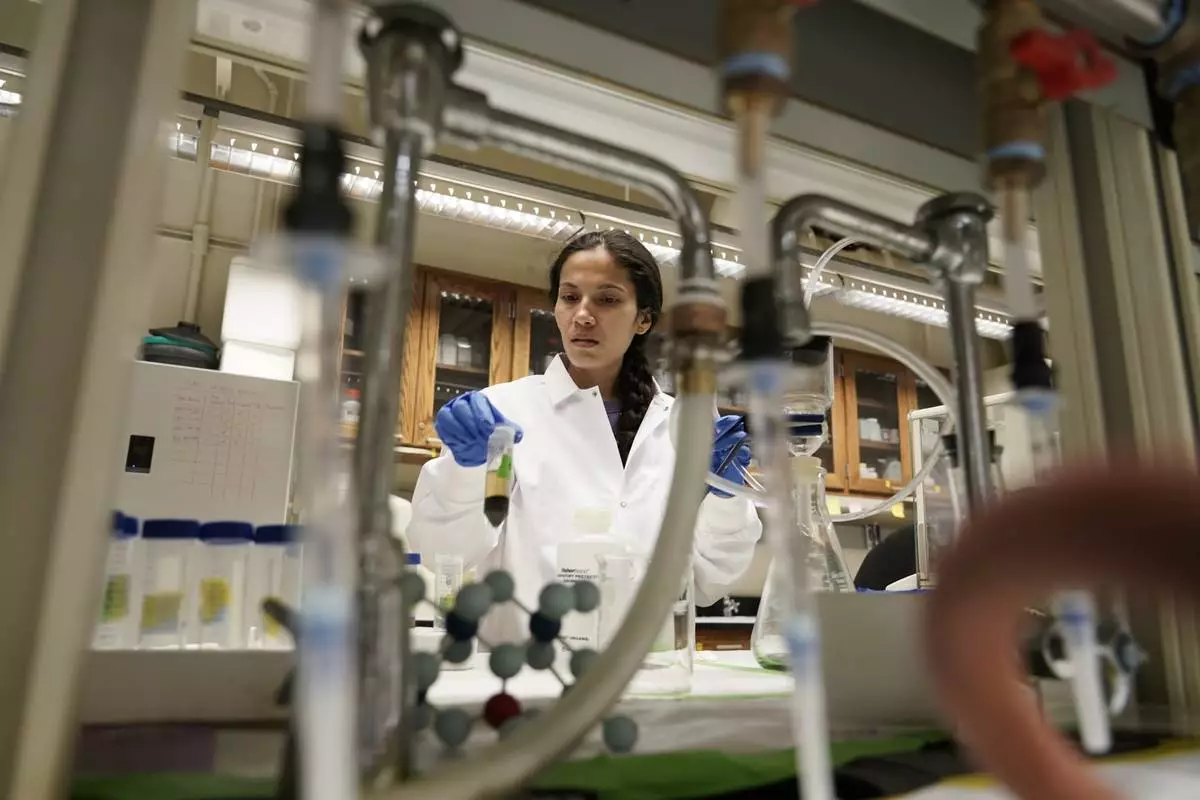

FILE - Soil researcher Asmita Gautam, a Ph.D. candidate at Purdue University, prepares a soil sample for carbon content analysis, July 13, 2023, in West Lafayette, Ind. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel, File)

FILE - Jude Addo-Chidie, a Ph.D. student in agronomy at Purdue University, places a probe in soil as he takes samples from a corn field July 12, 2023, at the Southeast-Purdue Agricultural Center in Butlerville, Ind. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel, File)