BUENOS AIRES, Argentina (AP) — Argentina's poverty rate dropped to 38.1% in libertarian President Javier Milei 's first year in office, the nation's official statistics agency reported on Monday, a closely watched measure reflecting the government's progress wrestling down what had been among the world's highest inflation rates.

The decline in poverty for the second half of 2024 — from July to December — marks an improvement from the 41.7% that Milei’s left-wing populist predecessors delivered for the second half of 2023. Milei swept to office late that year with a mandate to reverse the country’s economic decline brought about by years of reckless borrowing.

“These figures reflect the failure of past policies, which plunged millions of Argentines into precarious conditions,” Milei’s office said as the government statistics agency, known as INDEC, released its report. “The path of economic freedom and fiscal responsibility is the way to reduce poverty in the long term.”

But economists warn that the figure fails to capture the reality of ordinary people struggling to cope with the most radical austerity program in Argentina’s recent history. Milei’s blizzard of brutal cuts have hit everything from soup kitchens and bus fares to apartment rent and healthcare, eroding people’s purchasing power.

“There is a big gap between what the statistics say and what you feel on the streets,” said Tomás Raffo, an economist at Argentina's largest public sector workers union CTA. “We suffered a very strong blow where a lot more people went into poverty and now some of them have come out. ... But those who were poor before all this have gotten even poorer.”

In the first half of 2024 — the first six months of Milei’s presidency — INDEC reported that Argentina’s poverty rate had soared to 53%. On Monday, INDEC reported that the poverty rate for the preceding six months had slid by 14.8 percentage points to just over 38%, a knock-on effect of rapidly falling inflation.

Annual inflation plummeted to 66.9% last month compared to 276.2% a year earlier, according to INDEC.

“Politically, this is a very important achievement for the government, especially in this year of midterm elections,” said Camilo Tiscornia, director of C&T Asesores Económicos, a consultancy in Buenos Aires, noting this marked the lowest poverty rate since the first half of 2022. “It shows that what the government is doing is starting to work.”

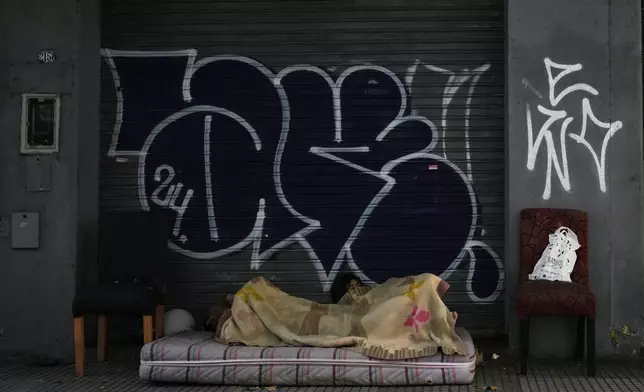

That bright picture can be difficult to make out on the streets of Buenos Aires, where a growing number of Argentines try to survive by mining dumpsters for sustenance and hawking their wares at traffic lights. This month the capital was shaken by violent clashes between police and protesters demanding higher pensions.

“I see a lot more people selling things and sleeping in the street,” said Lorena Jiménez, a 46-year-old selling stickers with two of her nine children on Monday. A former house cleaner who lost her job last year, she and her kids now sleep most nights on the street, using the $160 they receive each month — part of a recently increased government stipend to support impoverished children — to pay for occasional hotel stays.

Questions over the rosy statistics have mounted in a country where past administrations were caught doctoring official data for political means. After a major scandal, INDEC underwent a yearslong overhaul before regaining credibility in 2016.

“To me, this low inflation and poverty, it's a lie,” said Viviana Suarez, a 48-year-old insurance agent in Buenos Aires. “How does it make sense when you go to the supermarket and see the prices and realize you can't buy any food that's not on sale?"

A growing number of experts have voiced concern that, while perfectly orthodox, INDEC’s inflation measure has become misleading partly because its consumer price index is based on a basket of basic goods from 2004. The government applies the inflation numbers to calculate the poverty rate.

“It's very outdated and gives little weight to the things with prices that have recently risen the most," said Raffo, the economist with CTA.

For instance, CTA researchers say, food accounts today for a smaller share of an average household's budget than it did two decades ago. The index does not take into account digital subscriptions and other key expenses that have changed over time.

It also misses how critical private services like health care and education have become more expensive since Milei took office, and how residents are paying more for rent in a recently deregulated housing market, Raffo said.

He added: “INDEC is capturing very little of what is really happening in the economy.”

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

A person sleeps on the stairs of a church in Buenos Aires, Argentina, early Monday, March 31, 2025. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

A pedestrian flashes a victory sign as he passes posters that read in Spanish "No to IMF plundering" in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Monday, March 31, 2025. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

A worker pushes a dolly at a butcher in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Monday, March 31, 2025. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

A pedestrian passes a produce market in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Monday, March 31, 2025. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

People lie on a mattress outside a closed store in Buenos Aires, Argentina, early Monday, March 31, 2025. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)