PORT-AU-PRINCE, Haiti (AP) — Jean-Jacques Asperges once relished returning home after a long day working at a radio station in one of the world’s most dangerous places for journalists.

He had a roof and four walls for protection, but gang violence forced him and his family to flee their home twice.

Click to Gallery

Haitian journalists Johnny Ferdinand, left, Guerrier Dieuseul, center, and Ronald Desormes, right, work on the morning news broadcast from the studio of Radio TV Caraibe radio station in the Petion-ville neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Thursday, March 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Odelyn Joseph)

FILE - Journalists take cover from the exchange of gunfire between gangs and police in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Nov. 11, 2024. (AP Photo/Odelyn Joseph, File)

FILE - A wounded journalist talks on the phone after being shot by gangs at the General Hospital in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Dec. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Jean Feguens Regala, File)

FILE - The wife of a journalist who was shot during an armed gang attack on the General Hospital cries as an ambulance arrives with his body at a different hospital in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Dec. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Odelyn Joseph, File)

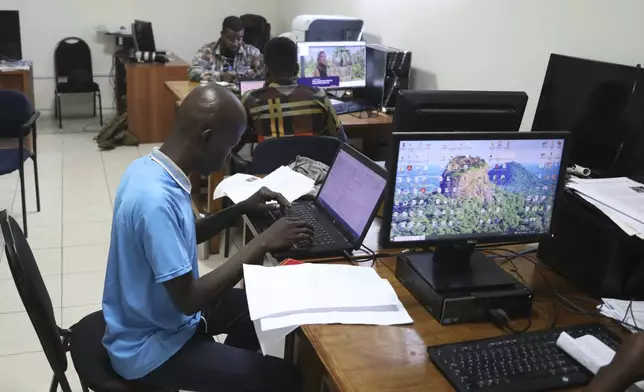

Text journalists work at Le Nouvelliste Newspaper in the Petion-Ville neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Thursday, March 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Odelyn Joseph)

FILE - People help a journalist overcome by tear gas, launched by police during a protest over the death of journalist Romelson Vilsaint, in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Oct. 30, 2022. Vilsaint died after being shot in the head when police opened fire on reporters demanding the release of one of their colleagues who was detained while covering a protest, witnesses told The Associated Press. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa, File)

Haitian journalists Johnny Ferdinand, left, Guerrier Dieuseul, center, and Ronald Desormes, right, work on the morning news broadcast from the studio of Radio TV Caraibe radio station in the Petion-ville neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Thursday, March 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Odelyn Joseph)

Journalists run for cover as protesters throw stones at a police car during a demonstration in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, March 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Odelyn Joseph, File)

Now, Asperges, 58, his wife and their two children are forced to sleep on the floor of a soiled and overcrowded makeshift shelter with thousands of other Haitians also left homeless by gang violence.

“Bullets fall here all the time,” he said.

Having lost all his work equipment, Asperges relies solely on his phone, but he remains undeterred like dozens of other journalists in Haiti who are under attack like never before. They are dodging bullets, defying censorship and setting personal struggles aside as they document the downfall of Haiti’s capital and the surge in violence blamed on powerful gangs that control 85% of Port-au-Prince.

Heavily armed gangs attacked at least three TV and radio stations in March. Two of the buildings were already abandoned because of previous violence, but gunmen stole equipment that had been left behind.

“It’s a message: You don’t operate without our permission, and you don’t operate at all in our turf,” said David C. Adams, an expert on press freedom issues in Haiti.

Gangs sent an even deadlier message on Christmas Eve, when they opened fire on journalists covering the failed reopening of Haiti’s largest public hospital, saying they had not authorized its reopening.

Two journalists were killed and at least seven others were injured, including Asperges, who was shot in the stomach. It was the worst attack on reporters in Haiti in recent history.

“Everyone is threatened. Everyone is under pressure,” said Max Chauvet, director of operations at Le Nouvelliste, Haiti’s oldest independent newspaper.

Donning a bulletproof vest emblazoned with “PRESS” on it is now a dangerous move in Haiti. What used to serve as a symbolic and physical shield has become a target.

At least 10 journalists covering a major March protest were attacked, including Jephte Bazil, a videographer who runs his own media company, Machann Zen Haïti.

He was threading his way through a protest in the Canapé-Vert neighborhood of Port-au-Prince when three men dressed in black and with their faces covered called him over.

“What the hell are you doing around here?” Bazil recalled them asking.

They searched his bag, took away his cellphone and demanded multiple forms of ID. Bazil handed over only his passport, keeping his ID card hidden because it stated he was from Martissant, a community that gangs seized several years ago. He was too scared to show it and possibly be accused of being a gang member or a sympathizer.

“I believe I could have been killed,” Bazil said.

After an interrogation that lasted at least half an hour, Bazil said the men released him. As he walked away, one followed him with a machete to see if he was headed where he said he was going.

Once he reached his destination, Bazil said the man told him: “If you had made any other turn, I would have…cut your head off.”

It was not the first time Bazil feared for his life. He was injured in December’s hospital attack and, in February, while covering a confrontation between police and gangs, his motorcycle was shot but he was spared.

“Journalists are targets now, whether police or gangs,” he said.

Haitians increasingly distrust the media, accusing local journalists of working for gangs. Meanwhile, gang members have taken to social media to threaten journalists. One gang leader said he would kidnap radio reporters and ensure they won’t ever talk into a microphone again, while another threatened a talk show host based outside of Haiti, saying that if he ever set foot in the country, it would be the last time he would do so.

As a result, Haiti’s Online Media Collective has advised that journalists not cover incidents involving armed groups.

“It’s not just journalists who are the victims, it’s press freedom itself,” said Obest Dimanche, the collective’s spokesperson.

But given the persistent attacks by heavily armed gangs in the capital and beyond, most journalists disregard that advice.

They travel in packs and zoom around on motorcycles through Port-au-Prince’s hilly neighborhoods, ducking in unison when shots are fired. At the end of the day, they check in on each other to ensure everyone returned safely home. Those who lost their homes to gang violence like Asperges go back to a shelter while others sleep on the floor of their media company.

“You feel in danger doing your job nowadays,” said Jean Daniel Sénat, a journalist at Le Nouvelliste and Magik9 radio station.

He lamented how journalists no longer have access to many neighborhoods in the capital because of gang violence: “If you can’t talk to the people…you won’t be able to report.”

The violence also has forced media companies to close, lay off reporters or stop printing, as was the case for Le Nouvelliste when gunmen attacked and occupied its offices last year. Since then, the newspaper has operated solely online.

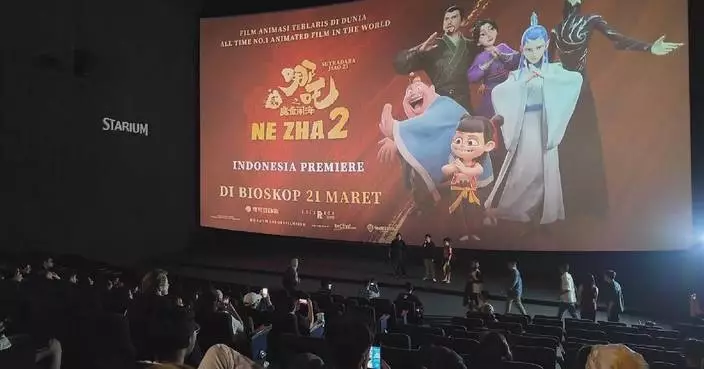

On March 13, Haiti’s prime minister condemned the attack on the building that once housed Radio et Télévision Caraïbes, the country’s oldest radio station, and pledged to protect media institutions.

Located on Rue Chavannes, the station’s former headquarters were considered a “heritage monument,” said journalist Richecarde Célestin, who works for the station.

Founded in 1949, the station has reported on Haiti’s tumultuous history: its coups, dictatorships and first democratic elections.

Considered one of Haiti’s most influential radio stations, it was a blow to many to see smoke and flames rising from the building.

“Every employee has a story with the space,” said journalist Dénel Sainton, who described the former headquarters as the “soul” of Radio et Télévision Caraïbes, which has been forced to move twice because of gang violence.

Also attacked that week was radio station Mélodie FM and TV station Télé Pluriel.

“What we’re seeing now, kind of the wholesale targeting of the media, is different,” said Adams, the expert on press freedom issues in Haiti. “In the old days, individual journalists were targeted.”

According to UNESCO, at least 21 journalists were reported killed from 2000 to 2022 in Haiti, with nine killed in 2022, the deadliest year for Haitian journalism in recent history.

The New York-based Committee to Protect Journalists reported one journalist killed in 2023 and two more in 2024.

Investigative journalist Gardy Saint-Louis recently told Télégramme360, an online news site, that he planned to go into hiding. Saint-Louis was quoted as saying that he began receiving anonymous calls in September 2024, and that death threats escalated into an attack in February, when armed men opened fire on his house.

Other journalists have fled Haiti, where attacks and killings are rarely solved.

Haiti ranks first globally as the country most likely to let journalists’ murders go unpunished, according to a 2024 CPJ report. Since 2019, seven killings remain unsolved, including that of Garry Tesse, a radio host whose mutilated body appeared six days after he vanished in 2022. Shortly before his death, Tesse accused a powerful prosecutor of plotting to kill him.

Coto reported from San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Follow AP’s coverage of Latin America and the Caribbean at https://apnews.com/hub/latin-america

FILE - Journalists take cover from the exchange of gunfire between gangs and police in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Nov. 11, 2024. (AP Photo/Odelyn Joseph, File)

FILE - A wounded journalist talks on the phone after being shot by gangs at the General Hospital in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Dec. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Jean Feguens Regala, File)

FILE - The wife of a journalist who was shot during an armed gang attack on the General Hospital cries as an ambulance arrives with his body at a different hospital in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Dec. 24, 2024. (AP Photo/Odelyn Joseph, File)

Text journalists work at Le Nouvelliste Newspaper in the Petion-Ville neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Thursday, March 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Odelyn Joseph)

FILE - People help a journalist overcome by tear gas, launched by police during a protest over the death of journalist Romelson Vilsaint, in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Oct. 30, 2022. Vilsaint died after being shot in the head when police opened fire on reporters demanding the release of one of their colleagues who was detained while covering a protest, witnesses told The Associated Press. (AP Photo/Ramon Espinosa, File)

Haitian journalists Johnny Ferdinand, left, Guerrier Dieuseul, center, and Ronald Desormes, right, work on the morning news broadcast from the studio of Radio TV Caraibe radio station in the Petion-ville neighborhood of Port-au-Prince, Haiti, Thursday, March 20, 2025. (AP Photo/Odelyn Joseph)

Journalists run for cover as protesters throw stones at a police car during a demonstration in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, March 19, 2025. (AP Photo/Odelyn Joseph, File)

ATLANTA (AP) — The U.S. House on Thursday approved legislation requiring documentary proof of U.S. citizenship for anyone registering to vote, something voting rights group have warned could disenfranchise millions of Americans.

The requirement has been a top election-related priority for President Donald Trump and House Republicans, who argue it's needed to eliminate instances of noncitizen voting, which is already rare and, as numerous state cases have shown, is typically a mistake rather than part of a coordinated attempt to subvert an election. It's already illegal under federal law for people who are not U.S. citizens to cast ballots and can lead to felony charges and deportation.

The bill, known as the Safeguard American Voter Eligibility Act, or the SAVE Act, now heads to the Senate, where its fate is uncertain because Republicans don't have a large enough majority to avoid a filibuster.

Here’s a look at key issues in the debate over a proof of citizenship requirement for voting:

If it eventually becomes the law, the SAVE Act would take effect immediately and apply to all voter registration applications.

“This has no impact on individuals that are currently registered to vote,” said Rep. Bryan Steil, a Wisconsin Republican who has been advocating for the bill.

Voting rights groups say there is more to the story. The law would affect voters who already are registered if they move, change their name or otherwise need to update their registration. That was acknowledged to some extent by the bill’s author, Republican Rep. Chip Roy of Texas, during a recent hearing on the legislation.

“The idea here is that for individuals to be able to continue to vote if they are registered,” Roy said. “If they have an intervening event or if the states want to clean the rolls, people would come forward to register to demonstrate their citizenship so we could convert our system over some reasonable time to a citizenship-based registration system.”

The SAVE Act compels states to reject any voter registration application in which the applicant has not presented “documentary proof of United States citizenship."

Among the acceptable documents for demonstrating proof of citizenship are:

— A REAL ID-compliant driver’s license that “indicates the applicant is a citizen.”

— A valid U.S. passport.

— A military ID card with a military record of service that lists the applicant’s birthplace as in the U.S.

— A valid government-issued photo ID that shows the applicant’s birthplace was in the U.S.

— A valid government-issued photo ID presented with a document such as a certified birth certificate that shows the birthplace was in the U.S.

In general, driver’s licenses do not list a birthplace or indicate that the card holder is a citizen – even many that are REAL ID-compliant.

REAL ID was passed by Congress in 2005 to set minimum standards for IDs such as driver’s licenses and requires applicants to provide a Social Security number and demonstrate lawful status either as a citizen or legal resident.

After years of delays, any driver’s license used for identification to pass through airport security will have to be REAL ID-compliant beginning May 7. U.S. passports will still be acceptable.

Although states designate REAL ID compliance on driver’s licenses with a marking such as a gold or black star, that alone would not indicate U.S. citizenship. People who are legal residents but not citizens also can obtain a REAL ID.

States are currently not required to label IDs with a “citizen” mark, although a handful of states (Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Vermont and Washington) offer a citizen-only REAL ID alternative that might meet SAVE Act requirements. Republicans say they hope more states will move in the direction of IDs that indicate citizenship.

“The structure is put in place now to -- I think there’s at least five states that do have the citizenship status as part of the REAL ID -- encourage more states to do so,” Roy said. “That would be part of the goal here.”

Adoption of REAL ID has been slow. As of January 2024, about 56% of driver’s licenses and IDs in the U.S. were REAL ID-compliant, according to data collected by the Department of Homeland Security.

Voting rights group say the list of documents doesn’t consider the realities facing millions of Americans who do not have easy access to their birth certificates and the roughly half who do not have a U.S. passport.

They also worry about additional hurdles for women whose birth certificates don’t match their current IDs because they changed their name after getting married. There were examples of this during local elections last month in New Hampshire, which recently implemented a proof of citizenship requirement for voting.

Republicans say there is a provision in the SAVE Act that directs states to develop a process for accepting supplemental documents such as a marriage certificate, which could establish the connection between a birth certificate and a government-issued ID.

They argue the process is similar to obtaining a U.S. passport or REAL ID-compliant driver’s license.

“We have mechanisms giving the state fairly significant deference to make determinations as to how to structure the situation where an individual does have a name change,” Roy said. “The process is specifically contemplated in this legislation.”

Democrats counter that the bill should have specified how this was to be done, rather than creating the potential to have 50 different rules.

The legislation says applicants who submit the federal voter registration form by mail must present documentary proof of U.S. citizenship in person to their local election office under a deadline set by their state.

Voting rights groups have noted this would be a huge barrier for people who live in more rural parts of the country, where the nearest election office might be hours away by car.

The SAVE Act directs states, in consultation with the U.S. Election Assistance Commission, to ensure that “reasonable accommodations” are made to allow individuals with disabilities who submit the form to provide proof of citizenship to their election official.

The legislation also considers that some states permit same-day voter registration and says, in those cases, voters must present proof of citizenship at their polling location “not later than the date of the election.”

That would mean that people who do not have such proof with them would have to return with their documents before polls close to be registered and have their ballot counted.

It’s less clear what this means for those states that have online voter registration systems or automatic voter registration set up through their state’s motor vehicle agency. Democratic state election officials have raised concerns that the legislation means these processes would no longer be operational under the proposal.

The legislation says anyone registering through a state motor vehicle agency also is required to provide proof of citizenship. It directs the Election Assistance Commission to issue guidance to state election officials about implementing the law’s requirements.

Republicans say any instance of voting by noncitizens, no matter how rare, is unacceptable and undermines confidence in U.S. elections.

Democrats respond by saying that voting by noncitizens is already illegal in federal elections —those for president and Congress — and penalties can result in fines and deportation. They say Congress should be more focused on helping states improve their ability to identify and remove any noncitizens who might end up on voter lists instead of forcing everyone to prove citizenship beforehand.

A recent review in Michigan identified 15 people who appear to be noncitizens who voted in the 2024 general election, out of more than 5.7 million ballots cast in the state. Of those, 13 were referred to the attorney general for potential criminal charges. One involved a voter who has since died, and the final case remains under investigation.

“Our careful review confirms what we already knew – that this illegal activity is very rare,” Michigan Secretary of State Jocelyn Benson said in a statement. “While we take all violations of election law very seriously, this tiny fraction of potential cases in Michigan and at the national level do not justify recent efforts to pass laws we know would block tens of thousands of Michigan citizens from voting in future elections."

Rep. Chip Roy, R-Texas, a member of the conservative House Freedom Caucus, walks outside of the closed-door House Republican Conference as Speaker of the House Mike Johnson, R-La., talks to fellow Republicans to push for a House-Senate compromise budget resolution to advance President Donald Trump's agenda, at the Capitol in Washington, Tuesday, April 8, 2025. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite)