CHARLESTON, W.Va. (AP) — The U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration is among the federal agencies selected for spending cuts by the Department of Government Efficiency.

Nearly three dozen MSHA offices would have their leases terminated if the plans come to fruition.

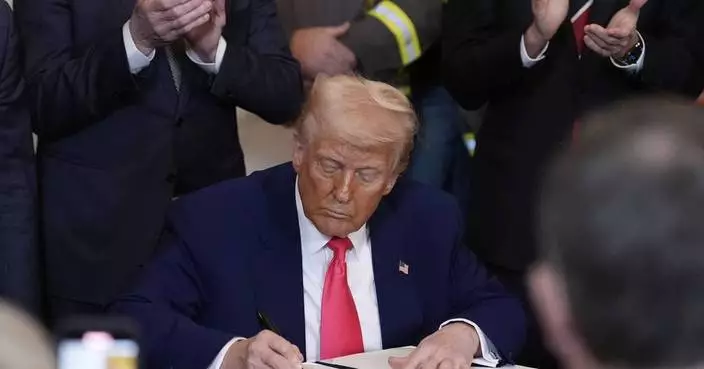

MSHA is responsible for enforcing U.S. mine safety laws. DOGE was created by President Donald Trump and is run by Elon Musk.

According to the DOGE website, 34 MSHA offices in 19 states have been targeted for closure. This includes seven in Kentucky, which would leave the fifth-leading coal producing state with just two MSHA facilities.

There also are four offices slated to close in Pennsylvania; two apiece in California, Nevada, New York, Ohio, Texas and West Virginia; and one each in Alabama, Arizona, Colorado, Illinois, Indiana, Minnesota, New Hampshire, Oregon, South Dakota, Tennessee and Wyoming.

Also under consideration for closure are the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement facilities in Lexington, Kentucky, and Tulsa, Oklahoma, shrinking the national footprint of an agency created during the Carter administration to restore land damaged by strip mining and reclaim abandoned and damaged minelands.

Ending the MSHA leases is projected to save $18 million. It’s unclear whether inspectors' positions and other jobs from those offices would be moved to other facilities.

MSHA was created by Congress within the Labor Department in 1978, in part because state inspectors were seen as too close to the industry to force coal companies to take the sometimes costly steps necessary to protect miners. MSHA is required to inspect each underground mine quarterly and each surface mine twice a year.

Agency inspectors are supposed to check every working section of a mine. They examine electrical and ventilation systems that protect miners from deadly black lung disease, inspect impoundment dams and new roof bolts, and make sure mining equipment is safe, said Jack Spadaro, a longtime mine safety investigator and environmental specialist who worked for MSHA.

Mining fatalities over the past four decades have dropped significantly, in large part because of the dramatic decline in coal production. But the proposed DOGE cuts would require MSHA inspectors to travel farther to get to a mine, and Spadaro said that could lead to less thorough inspections.

A review last month of publicly available data by the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center indicates that nearly 17,000 health and safety inspections were conducted from the beginning of 2024 through February 2025 by staff at MSHA offices in the facilities on the chopping block. MSHA, which also oversees metal and nonmetal mines, already is understaffed. Over the past decade, it has seen a 27% reduction in total staff, including 30% of enforcement staff in general and 50% of enforcement staff for coal mines, the law center said.

The coal industry has been in decline as utilities have installed more renewable energy and converted coal-fired plants to be fueled by cheaper and cleaner-burning natural gas.

U.S. coal production was at 1 billion tons (907,000 metric tons) in 2014 and fell to 578 million tons (524 million metric tons) by 2023, the latest year available, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. It has been in a long, steep decline for decades.

Coal industry deaths were in the hundreds throughout the 1950s and 1960s. After MSHA was created, deaths steadily decreased, then dropped even further in the last decade as a growing number of mining companies shut down and thousands of jobs were eliminated. There have been 11 or fewer deaths in each of the past five years, according to MSHA.

Coal employment rebounded from 2022 to 2023, rising 4.2% to 45,476. West Virginia employed the most miners at 14,000, followed by Kentucky at 5,000. About half of the nation’s 560 coal mines are located in West Virginia (165) and Kentucky (112). Despite having just 15 mines, Wyoming was the highest-producing coal state due to mechanization.

FILE - A miner gathers his thought before taking part in a rescue mission, Tuesday, Jan. 3, 2006, in Tallmansville, W.Va. (AP Photo/Haraz N. Ghanbari, Pool, File)

ROME (AP) — The Ukrainian soldiers clambered from the ruined house at gunpoint — one with arms raised in surrender to the Russian troops — and lay face-down in the early spring grass.

Two drones — one Ukrainian and one Russian — recorded the scene from high above the southern Ukrainian village of Piatykhatky. The Associated Press managed to get both videos. They offer very different versions of what happened next.

The Ukrainian drone video, which AP obtained from European military officials, shows soldiers with Russian uniform markings raising their weapons and shooting each of the four Ukrainians in the back with such ferocity that one man was left without a head.

“Out of all the executions that we’ve seen since late 2023, it’s one of the clearest cases,” said Rollo Collins of the Center for Information Resilience, a London group that specializes in visual investigations and reviewed the video at AP’s request. “This is not a typical combat killing. This is an illegal action.”

The Russian drone video, which AP located on pro-Kremlin social media, cuts off abruptly with the men lying on the ground — alive. “As a result of the work done by our guys, the enemy decided not to be killed and came out with their hands up,” wrote a Russian military blogger who posted the video.

Two videos. Two stories. In one, the prisoners appear to live. In the other, they die.

As evidence of potential war crimes continues to mount, many in Ukraine worry that the Trump administration’s about-face on the war will make it more difficult to establish a firm historical narrative about what has happened since Russia’s 2022 invasion and whether those most responsible for atrocities will ever be held accountable.

On March 13, the day European officials say the incident in Piatykhatky took place, U.S. representatives landed in Russia for ceasefire talks with President Vladimir Putin.

President Donald Trump, who has signaled that a prospective deal could see Ukraine surrender some territory and echoed Moscow’s talking points, called for a quick peace deal. His administration has pulled back support for Ukraine, including war crimes investigations, and is rebuilding relations with Putin — the very man many victims and prosecutors want to see in court.

“Whatever a peace agreement would be, Ukraine is not ready to forgive everything which happened in our territory,” Yurii Bielousov, head of the war crimes department for Ukraine’s prosecutor general, told AP. “In which form there will be accountability, that we don’t know at the moment.”

The killing of surrendering POWs in the Ukrainian video — a crime under international law — was not unique, according to Ukrainian prosecutors, international human rights officials and open-source analysts.

At least 245 Ukrainian POWs have been killed by Russian forces since the full-scale invasion, according to Ukrainian prosecutors. They allege it’s part of a deliberate strategy encouraged by Russian officials.

“It’s definitely part of the policy, which is fully supported by the top leaders of the Russian Federation,” Bielousov told AP. “This isn’t the action of specific commanders. It is supported on the top level.”

Asked about Russia's treatment of Ukrainian prisoners of war, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov said Russia treats surrendering Ukrainian troops in accordance with international law and does not encourage the killing of POWs.

“This is not a policy of the Russian side,” he told AP, and repeated Moscow's claims that atrocities committed by its troops in the Ukrainian town of Bucha were faked.

In the occupation of that town outside Kyiv early in the war, hundreds of Ukrainians were killed. Overwhelming evidence, including witness testimony, photos, CCTV videos, phone intercepts and corpses of civilians, substantiated those deaths.

The drone video in Piatykhatky was taken by Ukraine’s 128th Mountain Brigade, according to military officials with a European country that Ukrainian authorities shared the video with. The AP obtained it on condition of anonymity because the officials were not authorized to release it.

Intense fighting has devastated this crossroads in the Zaporizhzhia region. Fresh scorch marks stain the grass and what houses remain are missing roofs and windows. The battle has been part of a scramble to seize territory ahead of peace talks, with Russia seeking a strategic foothold to force Ukraine to restructure its logistics lines, according to military analysts.

Russian soldiers planted their flag amid the ruins of Piatykhatky last month, according to a drone video posted March 11 by pro-Kremlin bloggers.

Two days later, the Russian and Ukrainian drones recorded the surrender of the four Ukrainian soldiers about 100 meters (yards) away.

The Russian video shows an explosive drone flying in the window of the house where Ukrainians took cover, detonating with a flash.

Both countries' drones recorded one of the Ukrainians, arms raised and seemingly unarmed, leaving the shattered house. With a Russian soldier pointing his gun at him, the man plants himself spread-eagled next to his comrades on the ground.

European military officials who analyzed the video said the Russians are identifiable by red or white markings on their uniforms.

The Ukrainian video shows the Russians briefly searching their prisoners. Two more Russians arrive and consult with comrades. One pauses to use his radio.

What happens next was cut from the Russian video. One Russian walks to the prisoners, raises his gun with one hand and starts firing. Another soldier shoots, too. While he reloads, a third Russian joins in, firing at least two shots at close range that take off the helmet — and head — of one man. Then the soldier who’d been reloading finishes off the four Ukrainians, methodically shooting each, one by one.

Neither video shows how the first Ukrainian soldier got out of the house.

Ukraine’s 128th Mountain Brigade declined comment because the deaths are being investigated as a suspected war crime. Ukraine’s internal security agency confirmed to AP it has opened an investigation.

Russian military bloggers who posted the edited video said it shows the work of an assault unit from Russia’s 247th Airborne Regiment.

Russia’s Ministry of Defense did not respond to requests for comment on the incident.

Analysts at the Center for Information Resilience confirmed the videos were recorded by different drones, as well the location and identifying marks of the soldiers.

“For us, this is very much a quite clinical, methodical process of execution,” said Collins, the CIR analyst. “It follows on from a very consistent sort of trend that we’ve seen since at least December 2023.”

Russia also claims to have documented “systematic killings” of Russian POWs by Ukrainian troops but didn’t give overall numbers. In March, the Russian Foreign Ministry released testimony from Russian POWs exchanged by Ukraine who described beatings and torture in custody. Some reported “a practice of finishing off wounded Russian fighters, as well as executing combatants who have laid down their arms.”

The Investigative Committee, Russia’s top state criminal investigation agency, said in December it had opened over 5,700 criminal cases into alleged Ukrainian crimes since the start of the conflict.

The U.N. Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine has documented 91 extrajudicial killings of Ukrainian POWs since August 2024. During the same period, it found a single case of Ukrainian soldiers killing a Russian POW.

Bielousov, the Ukrainian war crimes prosecutor, said all such allegations against Ukrainian troops are being investigated.

Danielle Bell, head of the U.N. Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine, said the increase in POW killings by Russian forces hasn't happened in a vacuum. Russia enacted laws shielding soldiers from prosecution, she said, and officials have called for the killing or torture of Ukrainian POWs and endorsed reported extrajudicial killings. Multiple videos of POW killings have appeared online, some posted by Russian soldiers themselves, she noted, suggesting an environment of broad impunity.

“Calls on social media by public officials, amnesty laws, dehumanizing language within the context of impunity for these acts — it’s contributing to an environment that allows such acts or these crimes to take place,” she said.

Extrajudicial killings are among over 157,000 potential war crimes Ukrainian prosecutors are investigating. Ukraine has relied on international support to help process that flood of information and structure complex cases for both international and domestic courts.

That work is suffering since the Trump administration’s cuts to foreign aid.

Among those hit was the Ukrainian Helsinki Human Rights Union, which lost $5 million from cuts to the U.S. Agency for International Development. It had been using the money to collect evidence of offenses ranging from property damage to sexual assaults. The nongovernmental organization has cut staff, reduced operations and moved out of its Kyiv offices, executive director Oleksandr Pavlichenko told AP.

U.S. funding to groups investigating atrocities in Cambodia and Syria helped build war crimes cases years later. It took over two decades to bring top leaders of the Khmer Rouge before a U.N.-backed court on war crimes charges stemming from their brutal rule in the 1970s that led to 1.7 million deaths. Prosecutors relied on archives of the Documentation Center of Cambodia, established with U.S. government funding.

If not for that center, “there would have been no Khmer Rouge Tribunal. Period,” said Christopher “Kip” Hale, a criminal law expert who worked at the tribunal and has worked in Ukraine.

“To have durable peace, we have to have accountability. We have to invest now,” he said. "Without it, we see that ceasefires and armistices are just waiting periods for the next conflict to start.”

Leicester reported from Paris and Dupuy reported from New York. Volodymyr Yurchuk in Kyiv, Ukraine; Molly Quell in The Hague, Netherlands; Yuras Karmanau in Tallinn, Estonia; and Emma Burrows in London contributed.

This image taken from video that European military officials say was filmed by a Ukrainian drone in the southern Ukrainian village of Piatykhatky on March 13, 2025, shows three soldiers with red helmets and uniform markings identified as Russian surrounding four Ukrainian soldiers who appear to have surrendered and are laying on the ground. (Ukraine Military/European Defense Officials via AP)

This image taken from video that European military officials say was filmed by a Ukrainian drone in the southern Ukrainian village of Piatykhatky on March 13, 2025, shows a soldier, left, identified as Russian, pointing his gun at a Ukrainian soldier who appears to be surrendering after emerging from the ruins of a house to join other Ukrainian prisoners on the ground. (Ukraine Military/European Defense Officials via AP)

This image taken from video that European military officials say was filmed by a Ukrainian drone in the southern Ukrainian village of Piatykhatky on March 13, 2025, shows a soldier, center, identified as Russian, pointing his gun at a Ukrainian soldier who appears to be surrendering after emerging from the ruins of a house to join other Ukrainian prisoners on the ground. (Ukraine Military/European Defense Officials via AP)

This image taken from video that European military officials say was filmed by a Ukrainian drone in the southern Ukrainian village of Piatykhatky on March 13, 2025, shows three soldiers with red helmets and uniform markings identified as Russian surrounding four Ukrainian soldiers who appear to have surrendered and are laying on the ground. (Ukraine Military/European Defense Officials via AP)

This image taken from video that European military officials say was filmed by a Ukrainian drone in the southern Ukrainian village of Piatykhatky on March 13, 2025, shows a soldier, left, identified as Russian, pointing his gun at four Ukrainian soldiers on the ground who appear to have surrendered. (Ukraine Military/European Defense Officials via AP)

This image taken from video that European military officials say was filmed by a Ukrainian drone in the southern Ukrainian village of Piatykhatky on March 13, 2025, shows a soldier, left, identified as Russian, pointing his gun at a Ukrainian soldier who appears to be surrendering after emerging from the ruins of a house to join other Ukrainian prisoners on the ground. (Ukraine Military/European Defense Officials via AP)