SEOUL. South Korea (AP) — The United States has blocked imports of sea salt products from a major South Korean salt farm accused of using slave labor, becoming the first trade partner to take punitive action against a decadeslong problem on salt farms in remote islands off South Korea’s southwest coast.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection issued a withhold release order against the Taepyung salt farm, saying information “reasonably indicates” the use of forced labor at the company in the island county of Sinan, where most of South Korea’s sea salt products are made.

Under the order issued last Wednesday, Customs personnel at all U.S. ports of entry are required to hold sea salt products sourced from the farm.

Taepyung is South Korea's largest salt farm, producing about 16,000 tons of salt annually, which accounts for approximately 6% of the country’s total output, according to government data, and is a major supplier to South Korean food companies. The farm, located on Jeungdo island in Sinan and leasing most of its salt fields to tenants, has been repeatedly accused of using forced labor, including in 2014 and 2021.

South Korean officials stated that this was the first time a foreign government had suspended imports from a South Korean company due to concerns over forced labor.

In a statement to The Associated Press on Monday, South Korea’s Foreign Ministry said relevant government agencies, including the Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, have been taking steps to address labor practices at Taepyung since 2021. While not providing direct evidence, it said it assesses that none of the salt produced there now is sourced from forced labor. The ministry said it plans to “actively engage” in discussions with the U.S. officials over the matter.

The fisheries ministry said it plans to promptly review the necessary measures to seek the lifting of the U.S. order.

The widespread slavery at Sinan’s salt farms was exposed in 2014 when dozens of slavery victims — most of them with disabilities — were rescued from the islands following an investigation by mainland police. Some of their stories were documented by The Associated Press, which highlighted how slavery persisted despite the exposure.

U.S. Customs said it identified several signs of forced labor during its investigation of Taepyung, including “abuse of vulnerability, deception, restriction of movement, retention of identity documents, abusive living and working conditions, intimidation and threats, physical violence, debt bondage, withholding of wages, and excessive overtime.”

Lawyer Choi Jung Kyu, part of a group of attorneys and activists who petitioned U.S. Customs to take action against Taepyung and other South Korean salt farms in 2022, expressed hope that the U.S. ban would increase pressure on South Korea to take more effective steps to eliminate the slavery.

“Since the exposure of the problem in 2014, the courts have recognized the legal responsibility of the national government and local governments, but forced labor among salt farm workers has not been eradicated,” Choi said. “Our hope is that the export ban would force companies to strengthen due diligence over supply chains and lead to the elimination of human rights violations.”

Choi’s law firm and other groups representing salt farm slavery victims issued a statement urging the South Korean government to take stronger action to prevent the ongoing abuse, including harsher punishments for trafficking and forced labor crimes. They also criticized the lack of support measures for victims, such as employment and housing assistance, which has led some to return to salt farms.

Most of the salt farm slaves rescued in 2014 had been lured to the islands to work by brokers hired by salt farm owners, who would beat them into long hours of hard labor and confine them at their houses for years while providing little or no pay.

The slavery was revealed in early 2014 when two police officers from the capital, Seoul, disguised themselves as tourists to clandestinely rescue a victim who had been reported by his family as missing. One of the Seoul police officers told AP they went undercover because of concerns about collaboration between the island’s police and salt farm owners. Dozens of farm owners and job brokers were indicted, but no police or officials were punished despite allegations some knew about the slavery.

In 2019, South Korea’s Supreme Court upheld a lower court ruling that ordered the government to compensate three men who had been enslaved on salt farms in Sinan and the neighboring county of Wando, acknowledging that local officials and police failed to properly monitor their living and working conditions.

The salt farm slavery issue resurfaced in 2021 when around a dozen workers at Taepyung were discovered to have endured various labor abuses, including forced labor and wage theft.

FILE - A salt farm owner walks around his salt farm on Sinui Island, South Korea, Feb. 19, 2014. (AP Photo/Ahn Young-joon, File)

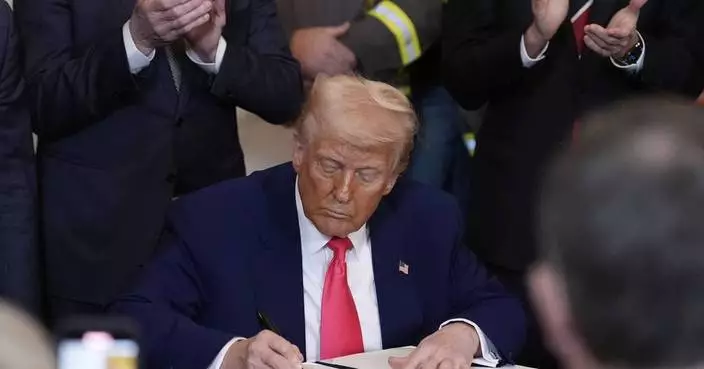

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Donald Trump’s new tariffs threaten to push up prices on clothes, mobile phones, furniture and many other products in the coming months, possibly ending the era of cheap goods that Americans enjoyed for about a quarter-century before the pandemic.

In return, White House officials hope the import taxes create more high-paying manufacturing jobs by bringing production back to the United States. It is a politically risky trade-off that could take years to materialize, and it would have to overcome tall barriers, such as the automation of most modern factories.

Even after Trump's U-turn on Wednesday that paused steep new tariffs on about 60 nations for 90 days, average U.S. duties remain much higher than a couple of months ago.

Trump has imposed a 10% tariff on all imports, while goods from China — the United States' third-largest source of imports — face huge 145% duties. And there are 25% taxes on imports of steel, aluminum, cars and roughly half of goods from Canada and Mexico.

As a result, the average U.S. tariff has soared from below 3% before Trump's inauguration to roughly 20% now, economists calculate, the highest level since at least the 1940s.

Should they remain in place, such high duties would reverse decades of globalization that helped lower costs for American shoppers.

Other trends, including factory automation and technological innovation, particularly in electronics such as TVs, have also brought down prices. But imports help keep prices in check, economists say, partly because of lower labor costs overseas and because increased competition in the U.S. market forces American companies to be more efficient.

“Freer trade has helped moderate inflation over the long term,” said Scott Lincicome, a trade analyst at the libertarian Cato Institute. “If we are entering a more restricted supply side ... then you’re likely to see more expensive stuff," Lincicome said.

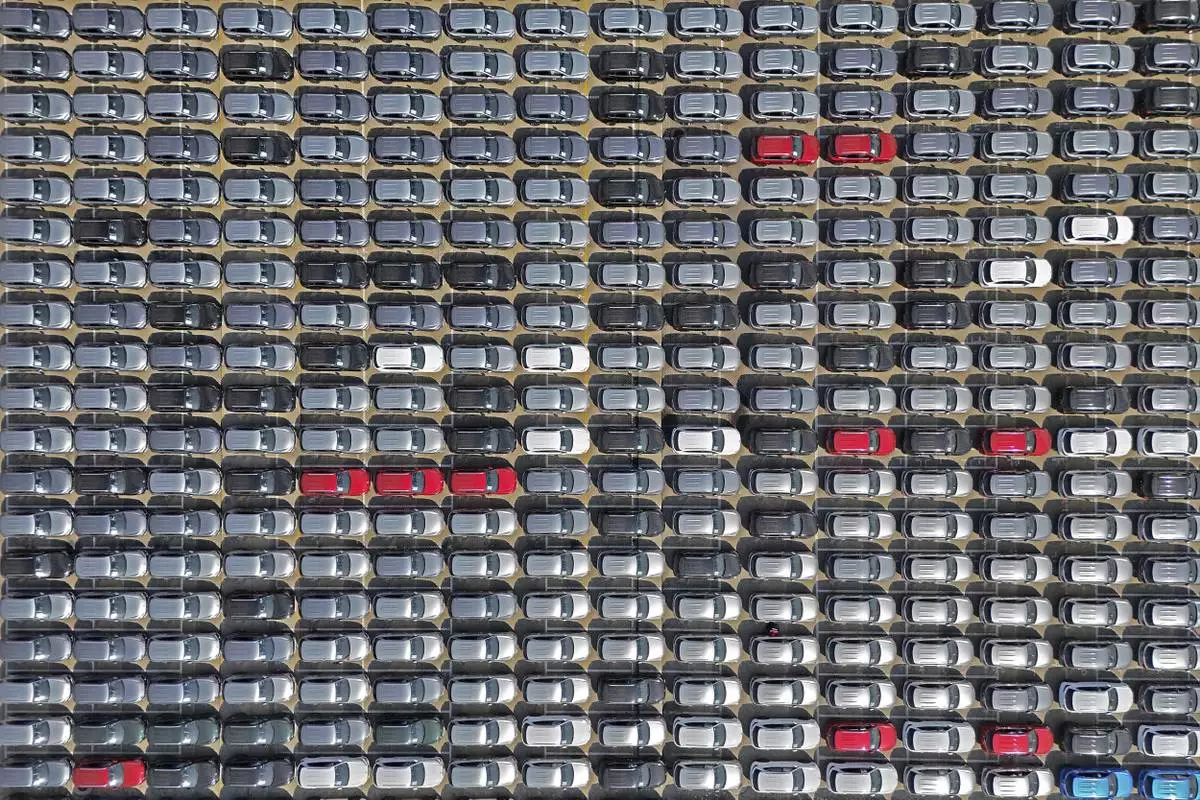

Bank of America estimates that the new duties could raise car prices an average of $4,500, even assuming that automakers absorb some of the tariffs’ impact. Such an increase would follow sharp price hikes of the past few years that have left the average price of a new car at a painful $48,000.

Aaron Rubin, CEO of ShipHero LLC, which provides software for merchants to help book shipments and track order deliveries, said his data indicates that retailers are already starting to raise prices to get ahead of the tariffs.

ShipHero's data captures prices on several million products equivalent to about 1% of overall U.S. e-commerce sales. Prices rose 3.9% on Sunday and Monday on a variety of goods compared with the week before Trump announced more tariffs, Rubin said.

If the tariffs hold, Apple is widely expected to raise the prices on iPhones and other popular products because the company’s supply chain is so heavily concentrated in China.

The iPhone 16 Pro Max could see one of the biggest sticker shocks, with its price potentially increasing by 29%. That could raise the starting price from $1,200 to $1,550, according to an estimate from UBS’s chief investment office.

After the double-digit inflation of the 1970s was defeated in the early 1980s, inflation still regularly topped 4% yearly until the mid-1990s, when freer trade and globalization began to intensify. From 1995 through 2020, it averaged less than 2.2%.

American shoppers reaped the benefits. Average clothing costs fell 8% from 1995 through 2020, at the same time that overall prices rose 74%, according to government data. Furniture costs were roughly unchanged. The average price of shoes rose just 10%.

Trump administration officials have at times acknowledged the prospect of higher prices from the tariffs.

In a speech last month to the Economic Club of New York, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent said, “Access to cheap goods is not the essence of the American dream.”

The administration's willingness to downplay the allure of cheap goods is a risky move, coming after the worst inflation spike in four decades from 2021 to 2023. The jump in prices for essentials such as groceries, gas and housing soured many voters on the economy under former President Joe Biden, despite low unemployment.

According to AP VoteCast, a nationwide survey of voters last November, about half of Trump’s voters said the high price of gas, groceries and other goods was the single most important factor in their vote. Another 43% of Trump voters said it was an important factor, even if it was not the most important consideration.

Some consumers say they are willing to pay more for U.S. goods.

Alisha Sholtis, 38, a nurse-turned-social media influencer, used to shop heavily on China-founded fast-fashion e-commerce site Temu, scooping up polyester tops and dresses for $5 to $25 and grabbing cheap electronics and toys. Products from Temu will now face huge new tariffs.

Yet Sholtis, who lives in Davison, Michigan, said she got tired of the clothes that fell apart after one washing and the toys that broke easily. She now shops elsewhere.

She applauds Trump’s goal of bringing some manufacturing back to the U.S. because she feels the move will lead to better quality. And she said she wouldn’t mind paying higher prices as a result.

“I would buy less of more higher quality things,” she said.

Kevin Hassett, Trump’s top economic adviser, acknowledged Sunday that “there might be some increase in prices” from the president’s tariffs.

But he noted that there have been trade-offs from globalization: “We got the cheap goods at the grocery store, but then we had fewer jobs,” he said on ABC's “This Week.”

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick predicted tariffs would force a manufacturing shift.

“The army of millions and millions of human beings screwing in little screws to make iPhones, that kind of thing is going to come to America,” Lutnick said during an April 6 appearance on CBS.

Analysts doubt that Apple could build phones in the U.S.

“The concept of making iPhones in the U.S. is a non-starter,” asserted Wedbush Securities analyst Dan Ives, reflecting a widely held view in the investment community that tracks Apple’s every move. He estimated that the current $1,000 price tag for an iPhone made in China or India would soar to more than $3,000 if production shifted to the U.S.

Shannon Williams, CEO of the Home Furnishings Association, a furniture trade group, said it can take years to set up a factory in the U.S. It's not clear if there would be enough workers either, given the low U.S. unemployment rate of 4.2%.

The most innovative furniture makers in the U.S. are using technology to reduce their labor needs. “They're going through it and completely automating their assembly line,” she said.

China exported 1.2 billion pairs of shoes to the United States last year, according to the Footwear Distributors and Retailers of America. About 26% of U.S. clothes were imported from China in 2023, one study found, and about 80% of U.S. toys.

Williams said furniture prices likely won't rise much anytime soon because most companies now import from other Asian nations, such as Vietnam or Malaysia.

Yet “globalization has definitely helped bring costs down,” she said. “There's a reason you could buy a $699 sofa in 1985 and buy a $699 sofa today."

D'Innocenzio reported from New York. Associated Press writers Michael Liedtke in San Francisco and Linley Sanders in Washington also contributed to this report.

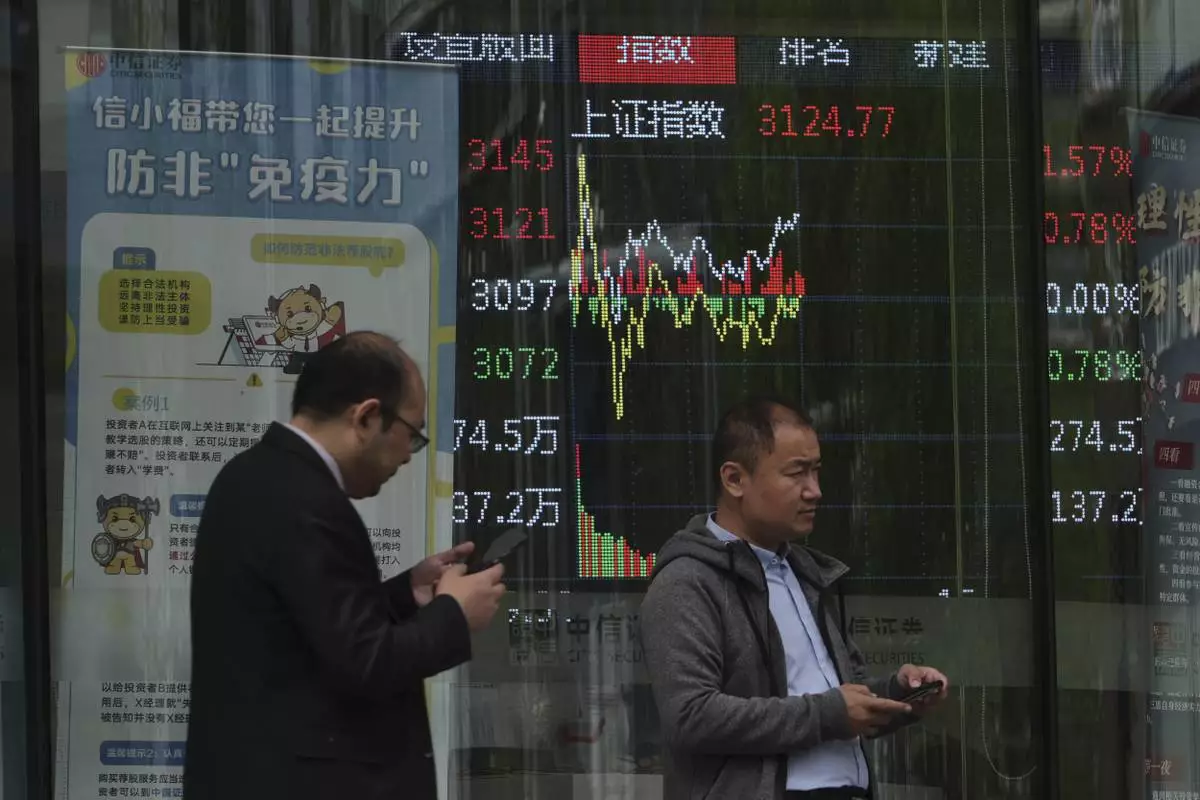

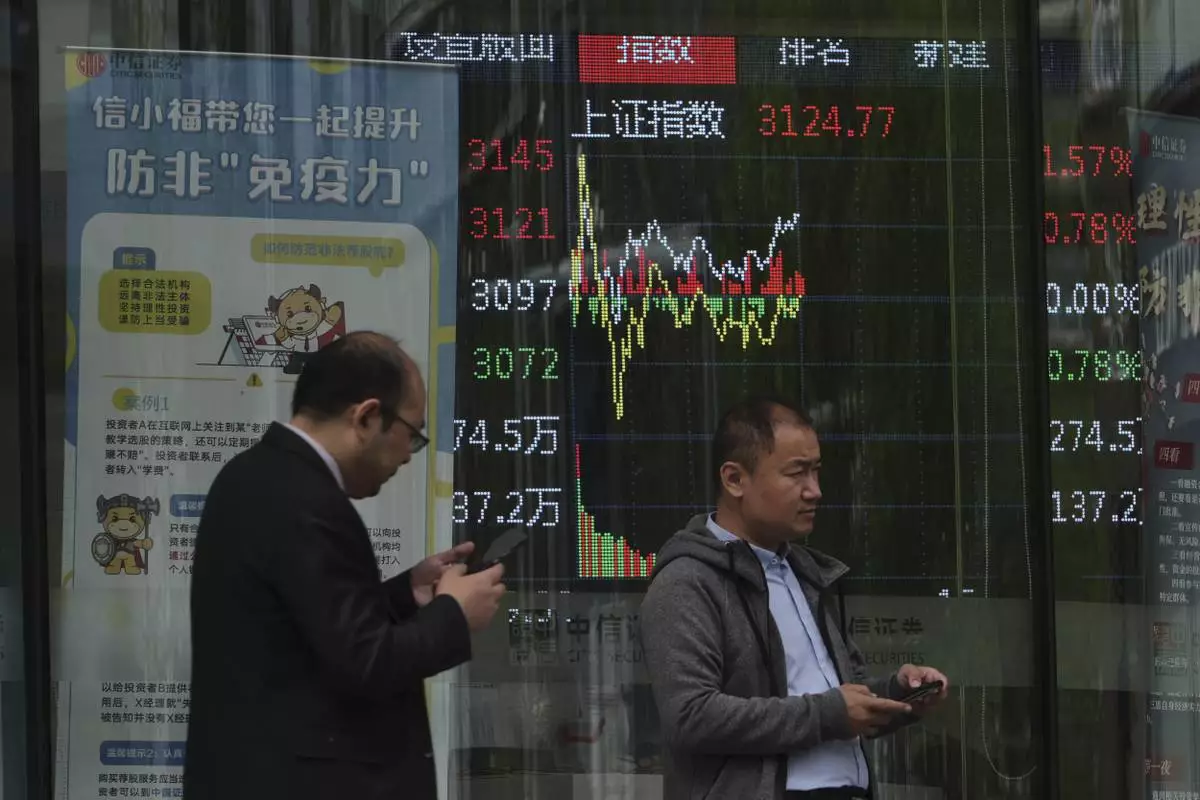

People walk past an electronic board displaying Shanghai shares trading index at a brokerage house, in Beijing, Tuesday, April 8, 2025. (AP Photo/Andy Wong)

Boxes of party supplies imported from China are stacked outside a store in the Toy District of Los Angeles, Wednesday, April 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

An aerial view of imported iron ore in a port in Yantai city in eastern China's Shandong province Sunday, March 30, 2025. (Chinatopix Via AP) CHINA OUT

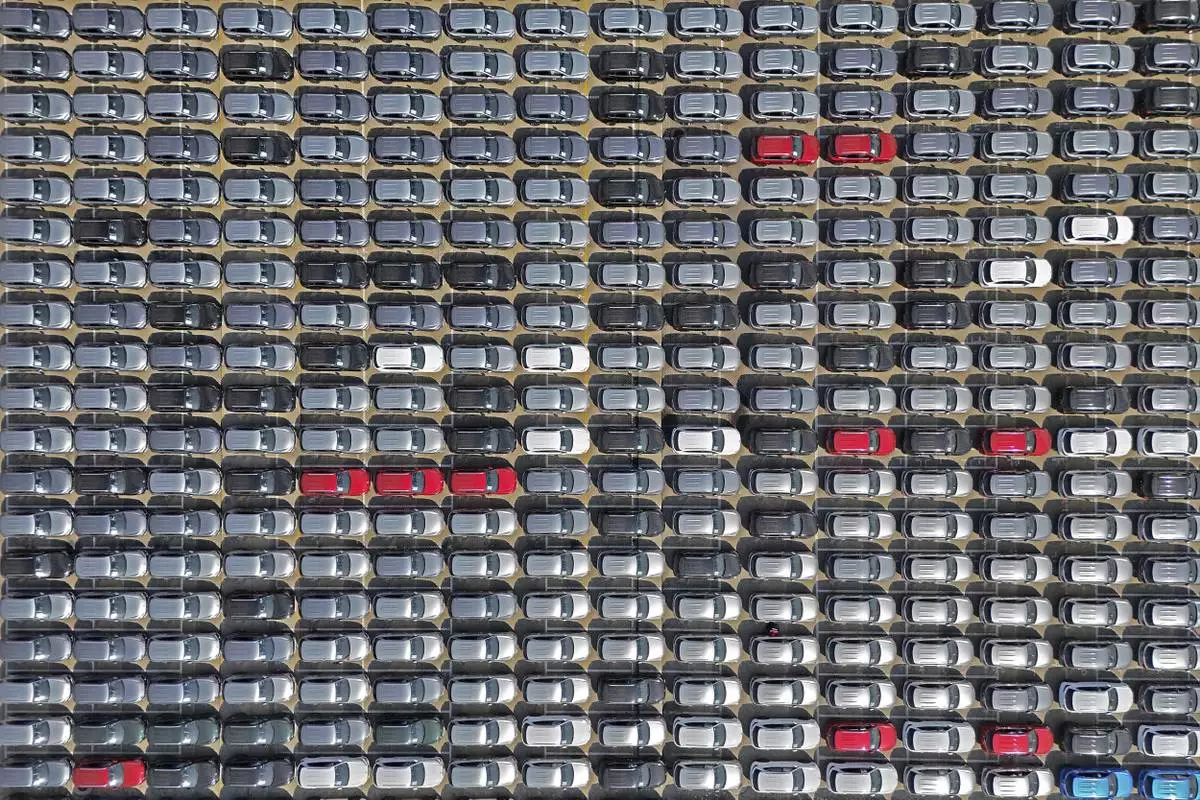

An aerial view of new cars waiting for shipment at a pier for "roll-on/roll-off" ships in Yantai city in eastern China's Shandong province Sunday, March 30, 2025. (Chinatopix via AP)

A vendor of halloween costumes wait for customers at the Yiwu International Trade Market in Yiwu, eastern China's Zhejiang province, Thursday, April 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan)

Foreigners shop for fashion accessories at the Yiwu International Trade Market in Yiwu, eastern China's Zhejiang province, Thursday, April 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan)

An aerial view of Xiasha Container Terminal on a canal in Hangzhou in east China's Zhejiang province Sunday, April 6, 2025. (Chinatopix Via AP)

U.S. flag themed wearables are displayed at the Yiwu International Trade Market in Yiwu, eastern China's Zhejiang province, Thursday, April 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Ng Han Guan)