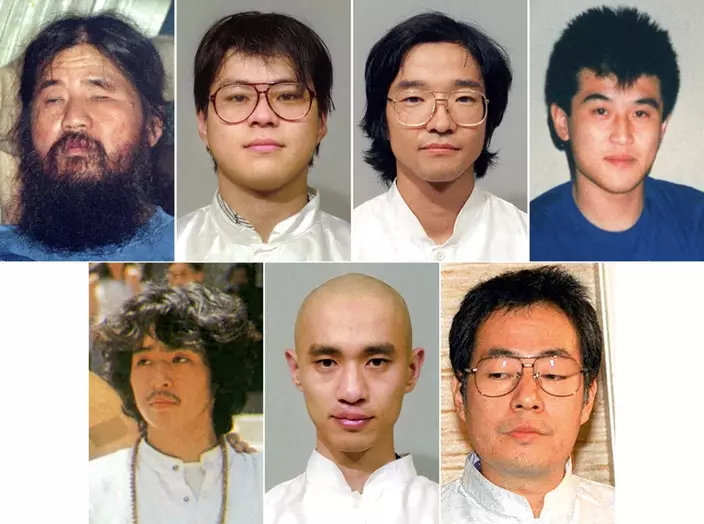

The executions Friday of a doomsday cult leader and six of his followers closed a chapter on one of Japan's most shocking crimes, the poison gas attack on rush-hour commuters in Tokyo's subway that killed 13 people and sickened more than 6,000.

The attack in 1995 woke up a relatively safe country to the risk of urban terrorism. The ensuing raid on the cult's compound near Mount Fuji riveted Japan, as 2,000 police officers approached with a canary in a bird cage. Shoko Asahara, the bearded, self-proclaimed guru who had recruited scientists and others to his cult, was found two months later, hiding in a compartment in a building ceiling.

A staff of Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun distributes their extra edition reporting doomsday cult leader Shoko Asahara was executed, in Tokyo Friday, July 6, 2018. Asahara and six followers were executed Friday for their roles in a deadly 1995 gas attack on the Tokyo subways and other crimes, Japan's Justice Ministry said. (AP Photo/Shuji Kajiyama)

The executions of the 63-year-old Asahara and the six cult members were announced by the Justice Ministry after they had been hanged, as is the practice in Japan. Two major newspapers issued extra editions and handed them out at train stations.

"This gave me peace of mind," Kiyoe Iwata, who lost her daughter in the subway attack, told broadcaster NHK. "I have always been wondering why it had to be my daughter and why she had to be killed. Now, I can pay a visit to her grave and tell her of this."

The executions were a long time coming, but they were expected as the last trial in the case had been completed and some of the condemned convicts had been transferred to other prisons earlier this year. Six other cult members remain on death row.

The subway attack was the most notorious of the cult's crimes, which was blamed for 27 deaths in all. Named Aum Shinrikyo, or Supreme Truth, it amassed an arsenal of chemical, biological and conventional weapons to carry out Asahara's escalating criminal orders in anticipation of an apocalyptic showdown with the government.

Japan's justice minister, who approved the hangings Tuesday, said she doesn't take executions lightly but felt these were justified because of the unprecedented seriousness of the crimes the seven committed.

"The fear, pain and sorrow of the victims, survivors and their families — because of the heinous cult crimes — must have been so severe, and that is beyond my imagination," Justice Minister Yoko Kamikawa told a news conference.

She said the crime affected not only Japan but also sowed fear abroad.

TV screens at an electrical appliance store show the image of doomsday cult leader Shoko Asahara in news reports, in Urayasu, near Tokyo, Friday, July 6, 2018. Asahara and six followers were executed Friday for their roles in a deadly 1995 gas attack on the Tokyo subways and other crimes, Japan’s Justice Ministry said. (Kyodo News via AP)

The seven executions in one day were the most since Japan began releasing information on executions in 1998. They were hanged in detention centers in Tokyo and three other places, spread out so the executions could be done at once.

Japan hangs several people in an average year but keeps the executions highly secretive. The country started disclosing the names of the executed and their locations only 11 years ago. Those executed learn their fate only when they are taken to the gallows. There are 117 convicts on death row.

Six of the seven, including Asahara, had been implicated in the subway attack. They included three scientists who led the production of the sarin gas and a man who drove a getaway vehicle.

Their other crimes include the 1989 murders of an anti-Aum lawyer and his wife and 1-year-old baby and a 1994 sarin attack in the city of Matsumoto in central Japan, which killed seven people and injured more than 140. An eighth person died after being in a coma for a decade.

On March 20, 1995, cult members used umbrellas to puncture plastic bags, releasing sarin nerve gas inside subway cars just as their trains approached the Kasumigaseki station, Japan's Capitol Hill, during the morning rush. Commuters poured out of subway stations in downtown Tokyo, and the streets were soon filled with troops in Hazmat suits and people being treated in first-aid tents set up outside.

FILE - This combination of file photos shows Aum Shinrikyo cult leader Shoko Asahara, from top left to right, his cult members, Tomomasa Nakagawa, Seiichi Endo, and Masami Tsuchiya. Other members from bottom left to right, Yoshihiro Inoue, Tomomitsu Nimi, and Kiyohide Hayakawa. Japan executed the leader and six followers of a doomsday cult Friday, July 6, 2018, for a series of deadly crimes including a sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway that killed 13 people in 1995. (Kyodo News via AP, File)

The convicted also assaulted and murdered wayward followers and people who helped members leave the cult.

Asahara, whose original name was Chizuo Matsumoto, founded Aum Shinrikyo in 1984. The cult attracted many young people, including graduates of top universities.

During his eight-year trial, Asahara talked incoherently, occasionally babbling in broken English, and never acknowledged his responsibility or offered meaningful explanations.

He was on death row for about 14 years. His family has said he was a broken man, constantly wetting and soiling the floor of his prison cell and not communicating with his family or lawyers. They had requested his mental treatment a retrial.

Some survivors of the cult's crimes opposed the executions, saying they would end hopes for a fuller explanation of the crimes.

Shizue Takahashi, whose husband was a subway deputy station master who died in the attack, also expressed regret that six of Asahara's followers had been killed.

A staff of Japanese newspaper Mainichi Shimbun distributes their extra edition reporting that doomsday cult leader Shoko Asahara was executed, in Tokyo Friday, July 6, 2018. Asahara and six followers were executed Friday for their roles in a deadly 1995 gas attack on the Tokyo subways and other crimes, Japan's Justice Ministry said. (AP Photo/Shuji Kajiyama)

"I wanted the others to talk more about what they did as lessons for anti-terrorism measures in this country, and I wanted the authorities and experts to learn more from them," she told a televised news conference. "I regret that is no longer possible."

The cult claimed 10,000 members in Japan and 30,000 in Russia. It has disbanded, though nearly 2,000 people follow its rituals in three splinter groups, monitored by authorities.

Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga said authorities are taking precautionary measures in case of any retaliation by his followers.