WASHINGTON (AP) — While eclipse watchers look to the skies, people who are blind or visually impaired will be able to hear and feel the celestial event.

Sound and touch devices will be available at public gatherings on April 8, when a total solar eclipse crosses North America, the moon blotting out the sun for a few minutes.

Click to Gallery

Minh Ha, assistive technology manager at the Perkins School for the Blind uses a flashlight to try a LightSound device, attached to an external speaker, for the first time at the school's library in Watertown, Mass., on March 2, 2024. Wanda Díaz-Merced, an astronomer who is blind, a co-creator of the device, says, “The sky belongs to everyone. And if this event is available to the rest of the world, it has to be available for the blind, too. ... I want students to be able to hear the eclipse, to hear the stars." (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

Minh Ha, assistive technology manager at the Perkins School for the Blind uses a flashlight to try a LightSound device, attached to an external speaker, for the first time at the school's library in Watertown, Mass., on March 2, 2024. Wanda Díaz-Merced, an astronomer who is blind, a co-creator of the device, says, “The sky belongs to everyone. And if this event is available to the rest of the world, it has to be available for the blind, too. ... I want students to be able to hear the eclipse, to hear the stars." (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

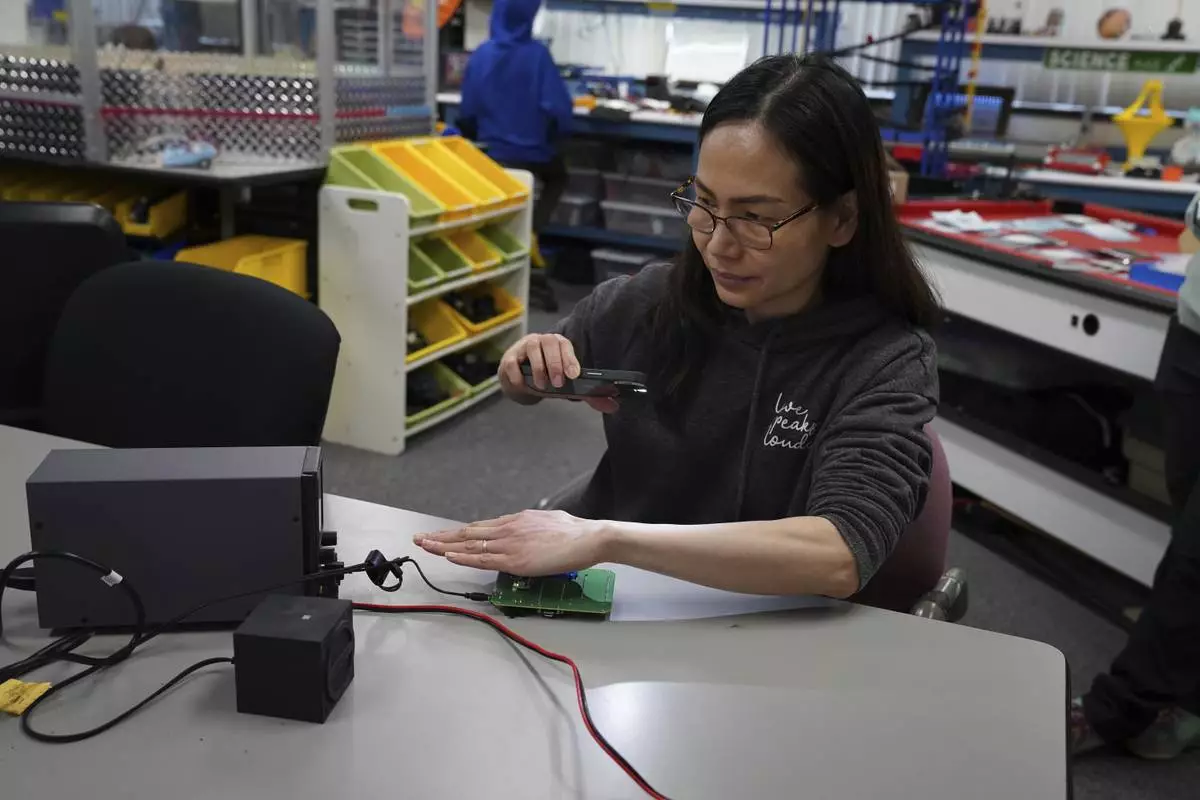

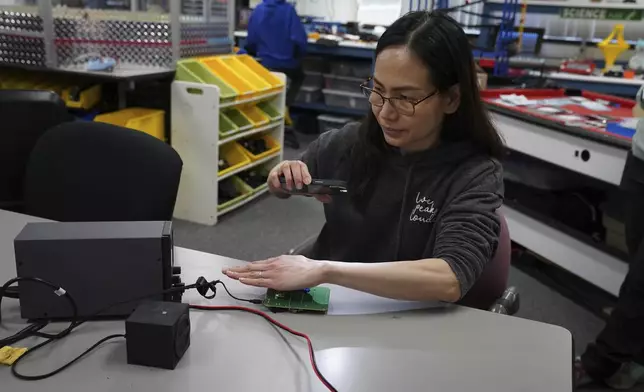

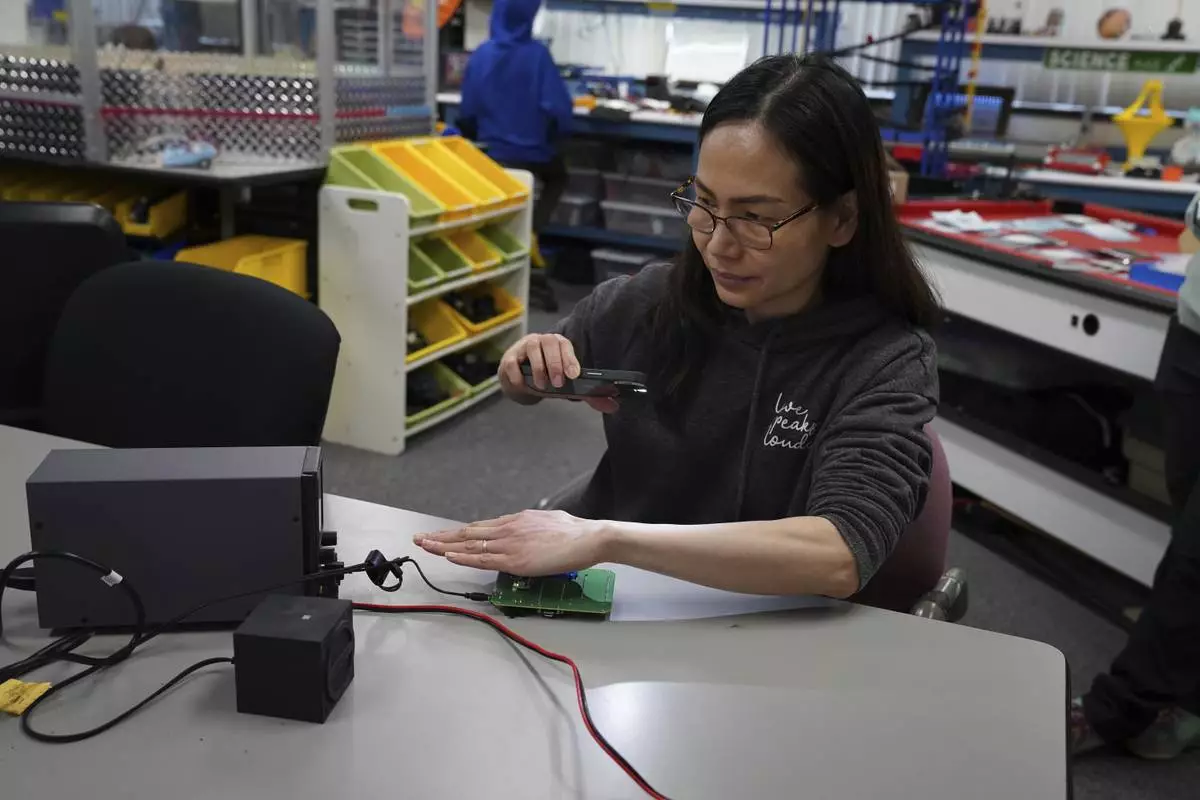

Katherine Tso tests components of a LightSound device at the New England Sci-Tech education center in Natick, Mass., on March 2, 2024. When the sun is bright, the device plays high flute notes. As the moon begins to cover the sun, the mid-range notes are those of a clarinet. Darkness is rendered by a low clicking sound. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

3D printed cases for LightSound devices are stacked together at the New England Sci-Tech education center in Natick, Mass., on March 2, 2024. A prototype was first used during the 2017 total solar eclipse in North America, and the handheld device has been at other eclipses in increasing numbers. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

Workshop participants assemble LightSound devices at the New England Sci-Tech education center in Natick, Mass., on March 2, 2024. The creators of the device are working with other institutions with the goal of distributing at least 750 devices to locations hosting eclipse events in Mexico, the U.S., and Canada. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

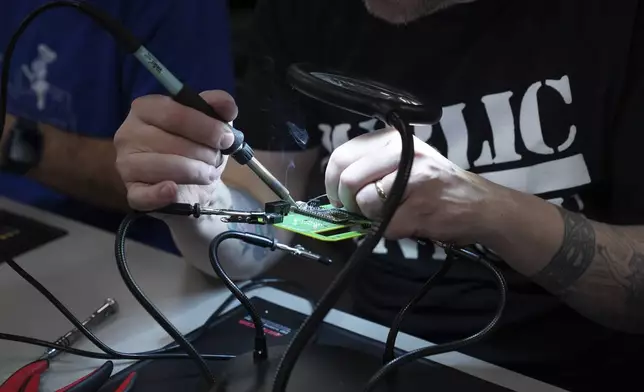

A workshop participant solders components for a LightSound device at the New England Sci-Tech education center in Natick, Mass., on March 2, 2024. The device is the result of a collaboration between Wanda Díaz-Merced, an astronomer who is blind, and Harvard astronomer Allyson Bieryla. Díaz-Merced regularly translates her data into audio to analyze patterns for her research. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

Minh Ha, assistive technology manager at the Perkins School for the Blind tries a LightSound device for the first time at the school's library in Watertown, Mass., on March 2, 2024. As eclipse watchers look to the skies in April 2024, new technology will allow people who are blind or visually impaired to hear and feel the celestial event. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

“Eclipses are very beautiful things, and everyone should be able to experience it once in their lifetime,” said Yuki Hatch, a high school senior in Austin, Texas.

Hatch is a visually impaired student and a space enthusiast who hopes to one day become a computer scientist for NASA. On eclipse day, she and her classmates at the Texas School for the Blind and Visually Impaired plan to sit outside in the school’s grassy quad and listen to a small device called a LightSound box that translates changing light into sounds.

When the sun is bright, there will be high, delicate flute notes. As the moon begins to cover the sun, the mid-range notes are those of a clarinet. Darkness is rendered by a low clicking sound.

“I’m looking forward to being able to actually hear the eclipse instead of seeing it,” said Hatch.

The LightSound device is the result of a collaboration between Wanda Díaz-Merced, an astronomer who is blind, and Harvard astronomer Allyson Bieryla. Díaz-Merced regularly translates her data into audio to analyze patterns for her research.

A prototype was first used during the 2017 total solar eclipse that crossed the U.S., and the handheld device has been used at other eclipses.

This year, they are working with other institutions with the goal of distributing at least 750 devices to locations hosting eclipse events in Mexico, the U.S., and Canada. They held workshops at universities and museums to construct the devices, and provide DIY instructions on the group's website.

“The sky belongs to everyone. And if this event is available to the rest of the world, it has to be available for the blind, too,” said Díaz-Merced. “I want students to be able to hear the eclipse, to hear the stars."

The Perkins Library — associated with the Perkins School for the Blind in Watertown, Massachusetts — plans to broadcast the changing tones of the LightSound device over Zoom for members to listen online and by telephone, said outreach manager Erin Fragola.

In addition to students, many of the library’s senior patrons have age-related vision loss, he said.

“We try to find ways to make things more accessible for everyone,” he said.

Others will experience the solar event through the sense of touch, with the Cadence tablet from Indiana's Tactile Engineering. The tablet is about the size of a cellphone with rows of dots that pop up and down. It can be used for a variety of purposes: reading Braille, feeling graphics and movie clips, playing video games.

For the eclipse, "A student can put their hand over the device and feel the moon slowly move over the sun," said Tactile Engineering’s Wunji Lau.

The Indiana School for the Blind and Visually Impaired started incorporating the tablet into its curriculum last year. Some of the school’s students experienced last October’s “ring of fire” eclipse with the tablet.

Sophomore Jazmine Nelson is looking forward to joining the crowd expected at NASA's big eclipse-watching event at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway, where the tablet will be available.

With the tablet, “You can feel like you’re a part of something,” she said.

Added her classmate Minerva Pineda-Allen, a junior. “This is a very rare opportunity, I might not get this opportunity again.”

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Science and Educational Media Group. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

Minh Ha, assistive technology manager at the Perkins School for the Blind uses a flashlight to try a LightSound device, attached to an external speaker, for the first time at the school's library in Watertown, Mass., on March 2, 2024. Wanda Díaz-Merced, an astronomer who is blind, a co-creator of the device, says, “The sky belongs to everyone. And if this event is available to the rest of the world, it has to be available for the blind, too. ... I want students to be able to hear the eclipse, to hear the stars." (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

Katherine Tso tests components of a LightSound device at the New England Sci-Tech education center in Natick, Mass., on March 2, 2024. When the sun is bright, the device plays high flute notes. As the moon begins to cover the sun, the mid-range notes are those of a clarinet. Darkness is rendered by a low clicking sound. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

3D printed cases for LightSound devices are stacked together at the New England Sci-Tech education center in Natick, Mass., on March 2, 2024. A prototype was first used during the 2017 total solar eclipse in North America, and the handheld device has been at other eclipses in increasing numbers. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

Workshop participants assemble LightSound devices at the New England Sci-Tech education center in Natick, Mass., on March 2, 2024. The creators of the device are working with other institutions with the goal of distributing at least 750 devices to locations hosting eclipse events in Mexico, the U.S., and Canada. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

A workshop participant solders components for a LightSound device at the New England Sci-Tech education center in Natick, Mass., on March 2, 2024. The device is the result of a collaboration between Wanda Díaz-Merced, an astronomer who is blind, and Harvard astronomer Allyson Bieryla. Díaz-Merced regularly translates her data into audio to analyze patterns for her research. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

Minh Ha, assistive technology manager at the Perkins School for the Blind tries a LightSound device for the first time at the school's library in Watertown, Mass., on March 2, 2024. As eclipse watchers look to the skies in April 2024, new technology will allow people who are blind or visually impaired to hear and feel the celestial event. (AP Photo/Mary Conlon)

HONG KONG (AP) — A former Hong Kong reporter of The Wall Street Journal on Tuesday said she'll sue the publication for sacking her because she joined a trade union.

Selina Cheng lost her job in July after a senior editor told her that her position was eliminated due to restructuring. However, Cheng believed the termination was linked to her refusal to comply with her supervisor’s request to withdraw from the election for the chairperson of the Hong Kong Journalists Association, a trade union for journalists that advocates for press freedom.

Cheng, now the chair of the association, said in a press briefing that she had sought mediation with her former employer through private channels and legal representatives, but their communication was “not fruitful" and her former employer refused to reinstate her job.

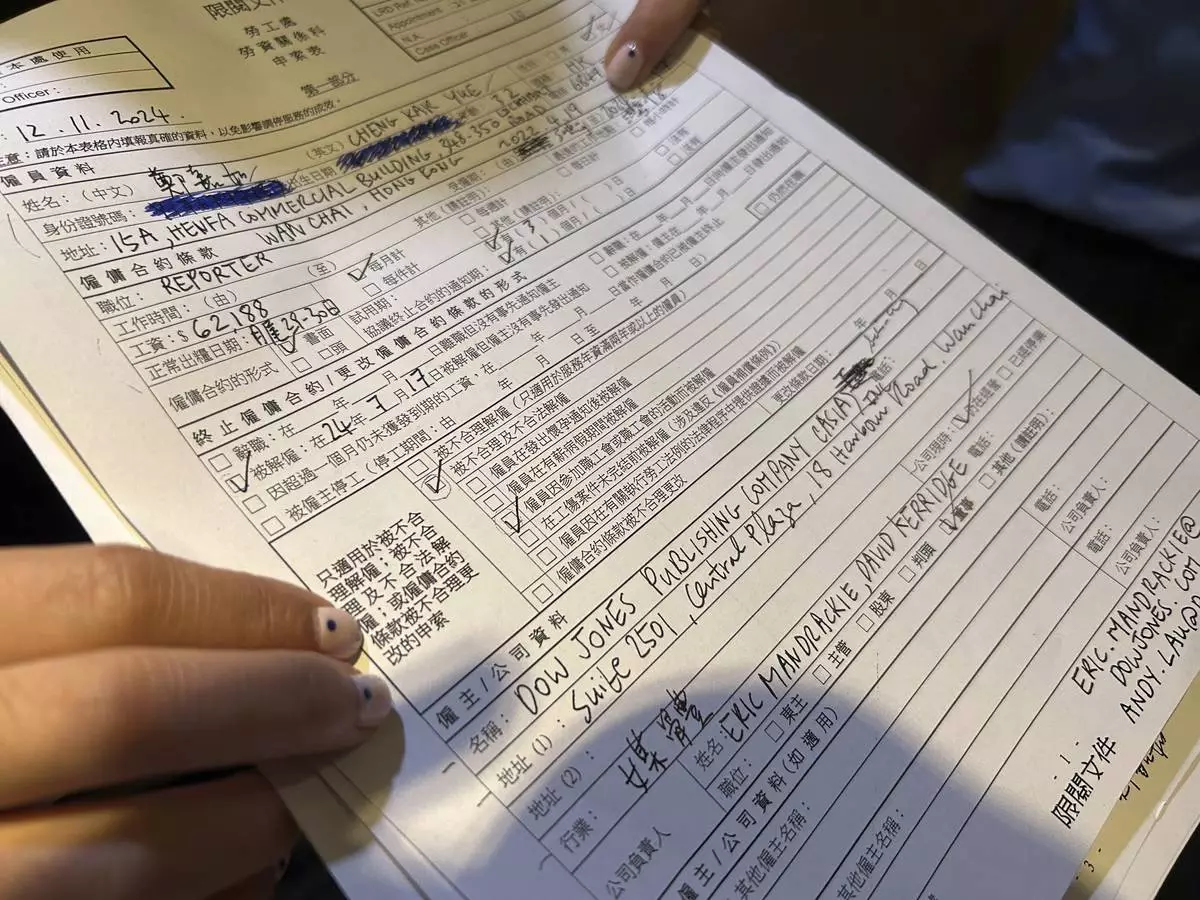

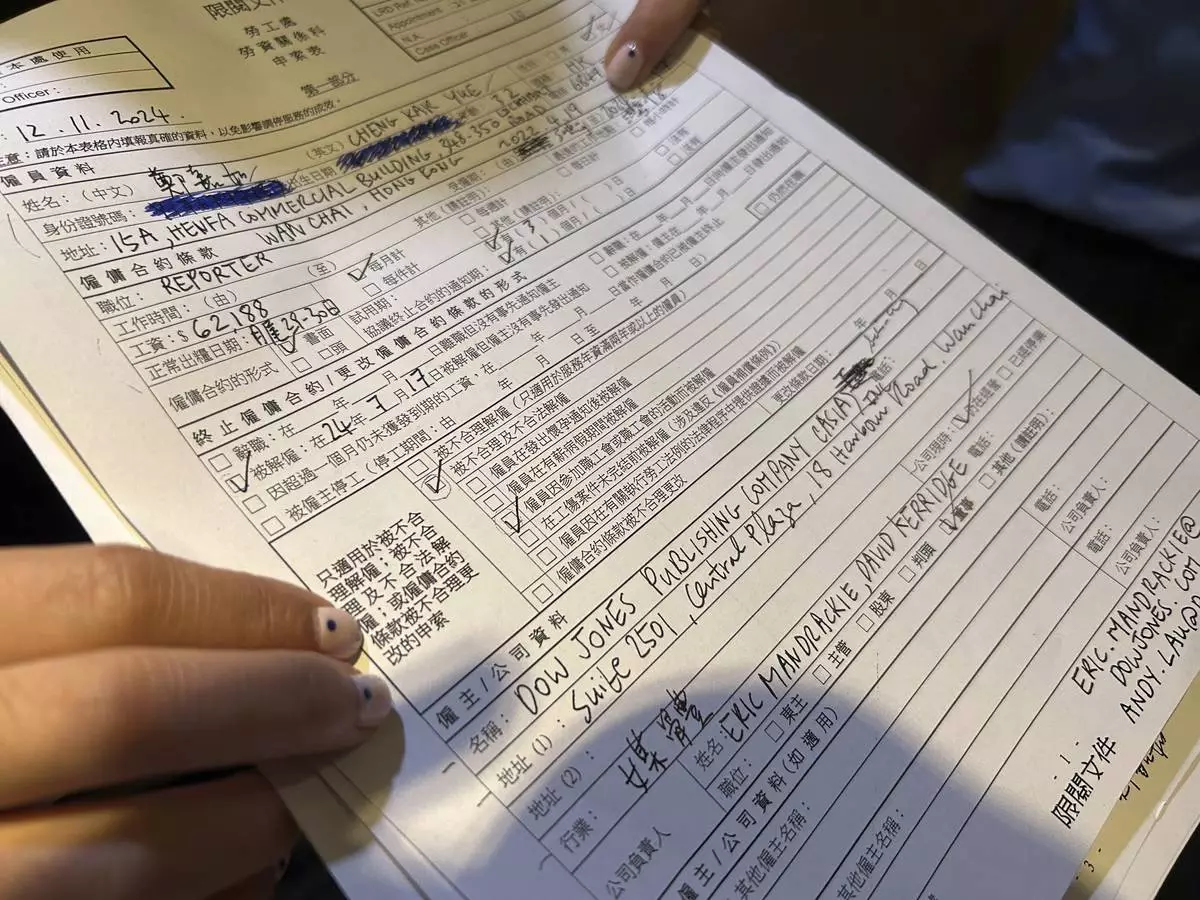

After the failed attempts, Cheng said she would file a civil claim at the Labor Tribunal, saying she had already brought evidence to the city's Labor Department. In a claim form shown to reporters, she stated she was fired unreasonably and illegally and it was due to her participation in a trade union.

“If the Wall Street Journal regrets this decision and agree that this wasn't right, there are ways to make repairs, perhaps still,” she said.

Cheng said she would meet with the department's investigators on Wednesday “to pursue this as a criminal matter.” She requested them to investigate her ex-employer for what she called “likely” violation of the employment ordinance.

Dow Jones, which publishes the newspaper, did not immediately comment.

Hong Kong journalists work in a narrowing space after drastic political changes in the city that was once seen as a bastion of media freedom in Asia.

After Beijing imposed a national security law in 2020, two local news outlets known for critical coverage of the government, Apple Daily and Stand News, were forced to shut down following the arrest of their senior management, including Apple Daily publisher Jimmy Lai. Lai is expected to testify in his defense next week in his landmark national security trial.

Two former editors at Stand News were convicted in August, the first journalists found guilty of sedition since the former British colony returned to China in 1997. One of them received a jail term of 21 months.

In March, Hong Kong enacted another security law, sparking worries among many journalists over a further decline in media freedom.

The termination of Cheng's contract in July sent shockwaves among Hong Kong's media workers. Cheng on Tuesday said her former employer insisted her job loss was a result of redundancy.

“Us being reporters, we hate being lied to by whoever it is, and least of all by our own supervisors and companies,” she said.

The Independent Association of Publishers’ Employees, a union run by and for the employees of Dow Jones, previously said in a statement that if Cheng was fired as what she claimed, the behavior was “unconscionable." It called on the publication to restore her job and provide full explanation about their decision to dismiss her.

Hong Kong ranked 135th out of 180 countries and territories in Reporters Without Borders’ latest World Press Freedom Index, down from 80 in 2021.

Selina Cheng, a former reporter at the Wall Street Journal, and chairperson of the Hong Kong Journalists Association shows reporters her claim form against her former employer for what she called unreasonable dismissal in Hong Kong on Tuesday, Nov.12, 2024. (AP Photo/ Kanis Leung)

Selina Cheng, a former reporter at the Wall Street Journal, and chairperson of the Hong Kong Journalists Association speaks to media in Hong Kong on Tuesday, Nov.12, 2024. Cheng said she'll sue the publication for sacking her because she joined a trade union. (AP Photo/ Kanis Leung)