SANTA ANA, Calif. (AP) — A California man convicted of stabbing to death a gay University of Pennsylvania student in an act of hate is expected to be sentenced Friday to life in prison.

Samuel Woodward, who is now 27, is scheduled to be sentenced in a Southern California courtroom for the murder of Blaze Bernstein nearly seven years ago. There is no question about the sentence Woodward will receive because the jury’s verdict carries a life sentence without parole, said Kimberly Edds, a spokesperson for the Orange County District Attorney’s office.

Defense attorney Ken Morrison previously said he would appeal the verdict.

Woodward was convicted this year of first-degree murder with an enhancement for a hate crime for killing Bernstein, a gay, Jewish college sophomore.

Bernstein, who was 19, disappeared in January 2018 after he went out at night with Woodward to a park in Lake Forest, about 45 miles (70 kilometers) southeast of Los Angeles. After Bernstein missed a dentist appointment the next day, his parents found his glasses, wallet and credit cards in his bedroom and tried to reach him, but he didn’t respond.

Authorities launched an exhaustive search and said Bernstein’s family scoured his social media and saw he had communicated with Woodward on Snapchat. Authorities said Woodward told the family that Bernstein had gone to meet a friend in the park that night and didn’t come back.

Days later Bernstein’s body was found in a shallow grave in the park. He had been repeatedly stabbed in the face and neck.

The question during Woodward's monthslong trial was not whether he killed Bernstein but why and the circumstances under which it happened. Prosecutors said Woodward was affiliated with the violent anti-gay, neo-Nazi extremist group Atomwaffen Division, while Morrison said his client didn't plan to kill anyone or hate Bernstein and faced challenging personal relationships due to a long-undiagnosed autism spectrum disorder.

The case took years to go to trial amid a series of delays and stoked public outcry in Southern California, where residents fanned out in 2018 to try to help authorities find Bernstein after he suddenly went missing.

Woodward testified during his trial and gave slow, delayed replies to lawyers' questions with his long hair partly covering his face.

Bernstein and Woodward attended the same high school, Orange County School of the Arts, and connected via a dating app in the months before the killing. Woodward said he picked up Bernstein, went to a nearby park and repeatedly stabbed Bernstein after trying to grab a cellphone he feared had been used to photograph him.

Morrison, the defense lawyer, said Woodward was confused about his sexuality after growing up in a politically conservative and devout Catholic family where his father openly criticized homosexuality.

But prosecutors told a different story. They said Woodward had repeatedly targeted gay men online by reaching out to them and abruptly breaking off contact, while keeping a hateful, profanity-laced journal of his actions.

Authorities said they also found a black Atomwaffen mask with traces of blood, a folding knife with a bloodied blade and a host of anti-gay, antisemitic and hate group materials in a search of his family's home in Newport Beach, California.

FILE - Orange County Deputy Sheriffs escort Samuel Woodward into Orange County Superior Court for opening statements of his murder trial for the stabbing death of Blaze Bernstein, Tuesday, April 9, 2024, in Santa Ana, Calif. (Frederick M. Brown/Pool Photo via Orange County Register, via AP, File)

FILE - A 2017 photograph of Samuel Woodward is displayed during Assistant Public Defender Ken Morrison's closing arguments in Woodward's murder trial, at Orange County Superior Court in Santa Ana, Calif., Monday, July 1, 2024. (Leonard Ortiz/The Orange County Register via AP, Pool, File)

FILE - Samuel Woodward testifies in Orange County Superior Court, June 13, 2024, in Santa Ana, Calif. (Leonard Orti/The Orange County Register via AP, Pool, File)

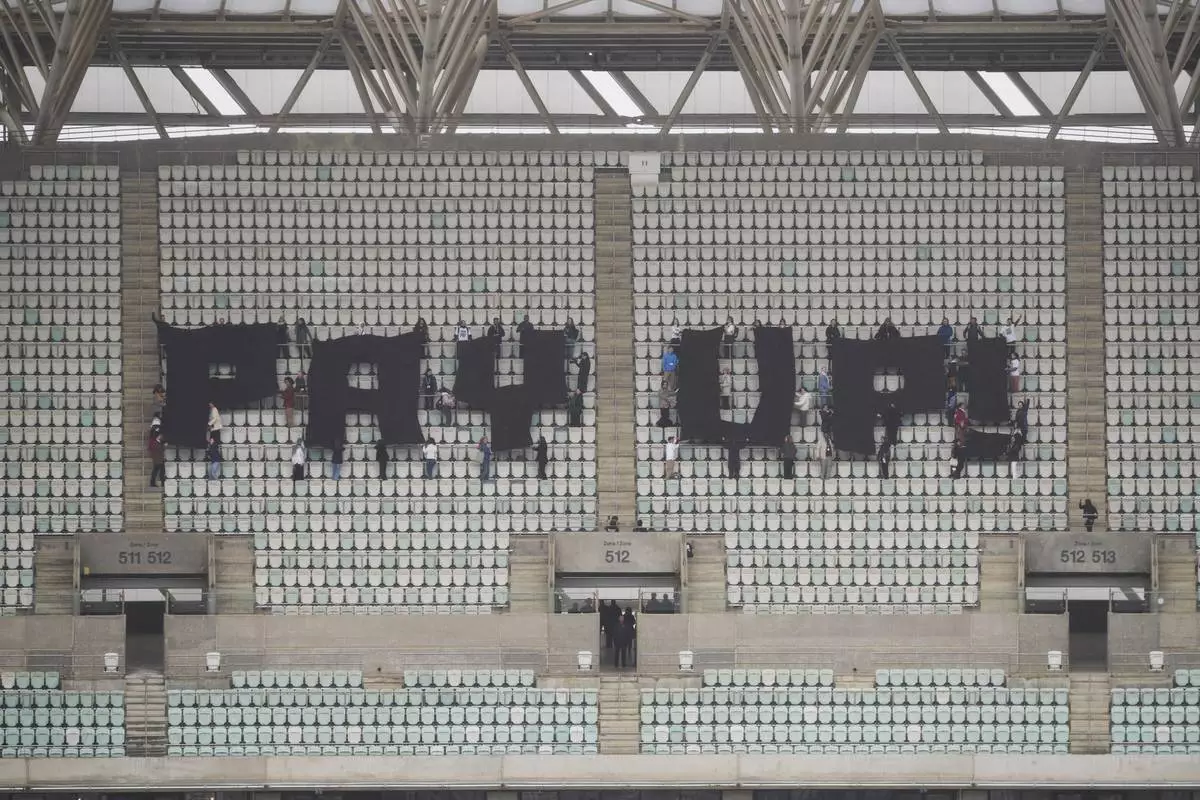

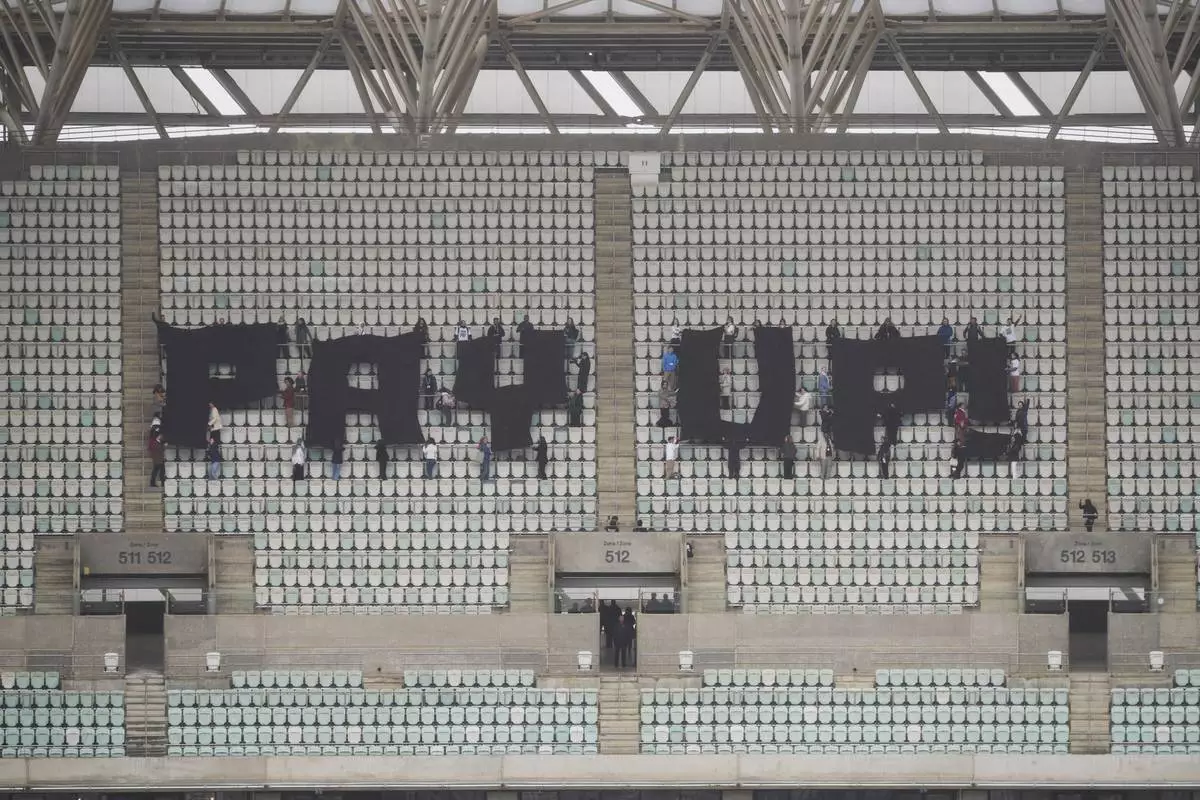

BAKU, Azerbaijan (AP) — In the nosebleed seats of a nearly-empty Baku Olympic stadium coated with a layer of dust, activists used a giant banner to beam the words “Pay Up” to the world.

The protest took weeks of thought and planning, but most of the attendees at this year's U.N. climate talks didn't see or hear it — except for maybe some in the COP29 presidency offices right below. The majority of the people involved in deciding the financial future of climate action at the talks remained in the sprawling venue, under white tarps with no windows.

It’s “really hard to make our demands heard,” said Bianca Castro, a climate activist from Portugal. She’s been to several COPs in the past and remembers years when there were thousands of protestors in the streets, and a multitude of strikes and actions throughout the event. But at the stadium's seats, they were told exactly where and when they could stand and chants were restricted. A United Nations climate change spokesperson said that the action was in a part of the venue that isn’t open to participants, and involved extensive dialogue among the participants, facility managers and health and safety officers.

Still, Castro said the difficulty of making an impact meant many are "losing hope in the in the process."

People involved in protests say they have felt a trend in recent years of stricter rules from the United Nations organizers with COPs being held in countries whose governments limit demonstrations and the participation of civil society. And some community spaces for prepping and organizing have had to resort to going underground because of security concerns. But the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change — who run the COPs — say the code of conduct that governs the conferences has not changed, nor has the way it's applied, and COP29 organizers say there's space across the venue for participants to “make their voices heard in line with the UNFCCC code of conduct and Azerbaijan law safely and without interference.”

Despite the challenges and what some see as a depressing mood, activists say it remains a critical time to speak up about the historical and present-day injustices that are in desperate need of money and attention.

It's especially true this year at a COP where the theme is finance, because voices from the Global South play a pivotal role in bringing ambitious demands to the negotiating table, said Rachitaa Gupta, who coordinates a global network of organizations advocating for climate justice. But she said that there have been more and more defamation rules each year that prohibit protestors from calling out specific countries or names.

“We do feel that the restrictions have reached a stage where it’s a constant battle on what we can say,” Gupta said. Activists can’t name specific countries, people or businesses in line with the UNFCCC’s code of conduct.

Meanwhile, across town in a downtown Baku building, activists paint, snip fabric and sculpt with cardboard and papier-mache in a quest for visually compelling symbols of climate action. The art space was once a place of community, where people came to pour their feelings into a creative outlet, said Amalen Sathananthar, coordinator at a collective called the Artivist Network. But now his team keeps the art space private and doesn't reveal its location because of security concerns.

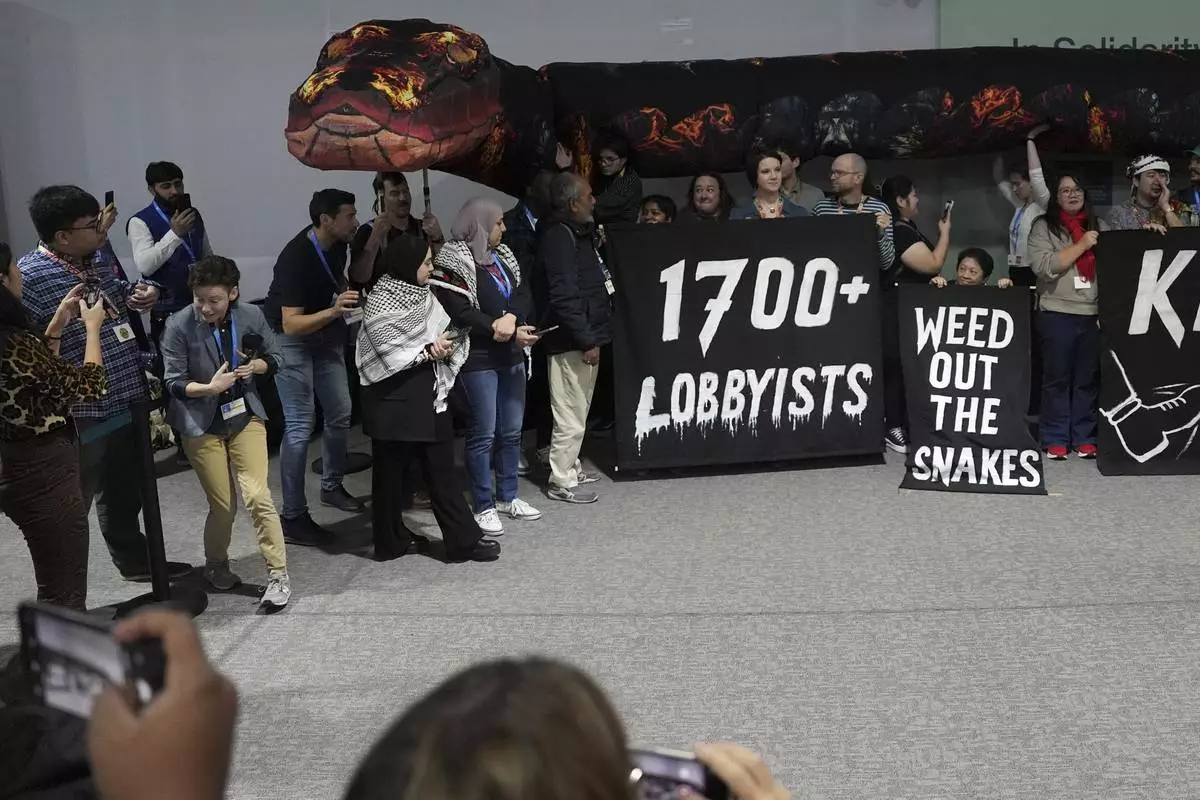

Restrictions, though, can breed creativity among the artists designing the banners, flags and props that demonstrators use during protests. In the absence of naming specific people or countries, or carrying country flags, they instead have to come up with other imagery to get their messages across.

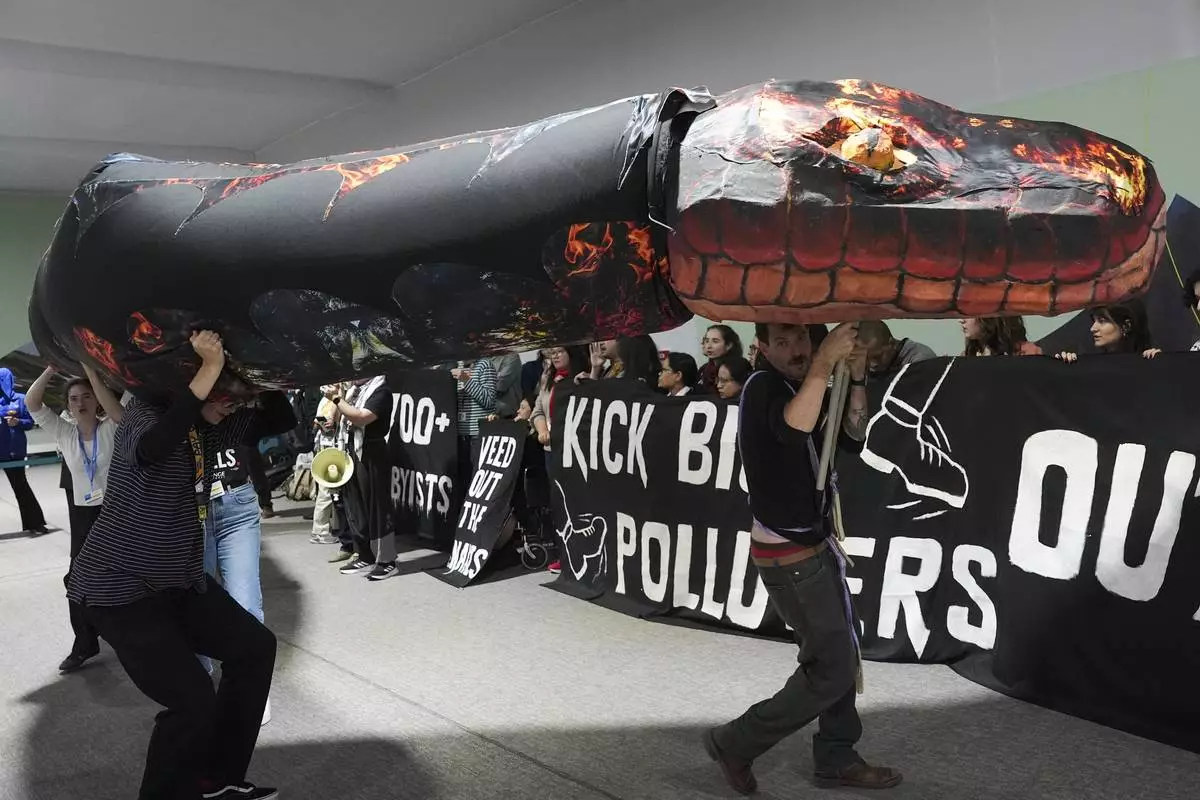

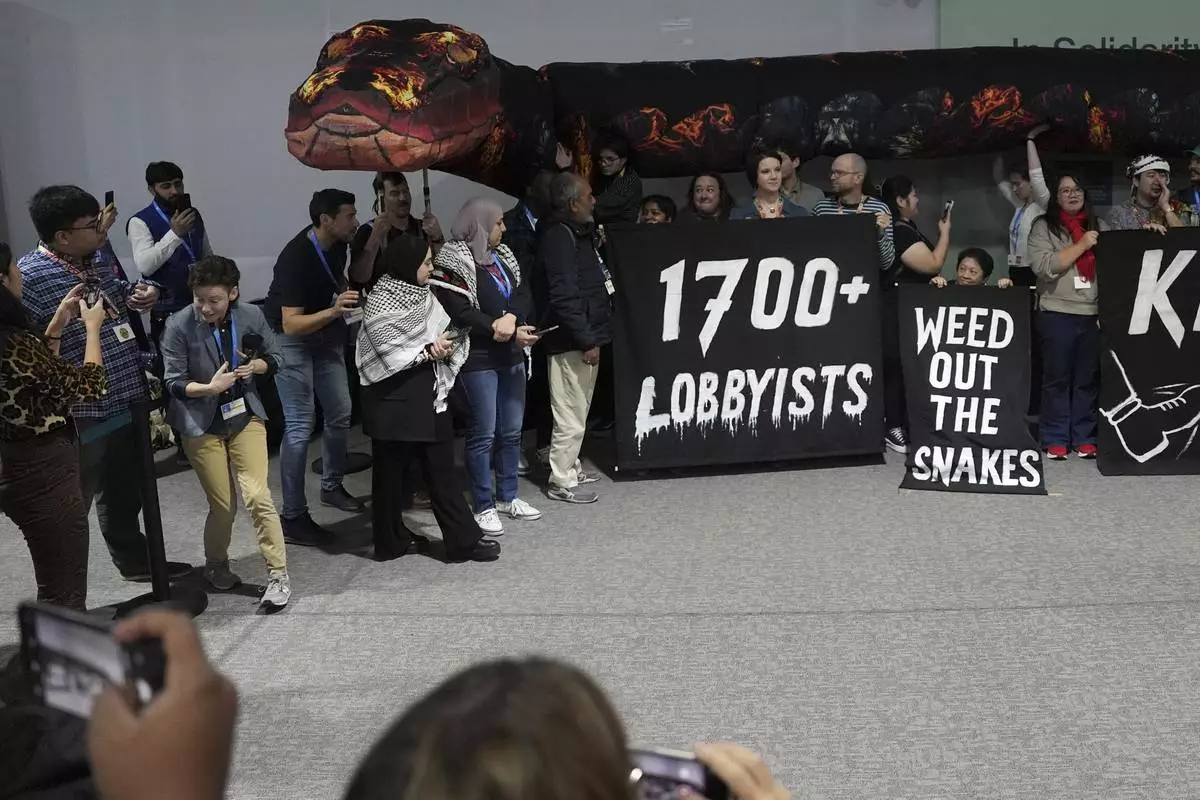

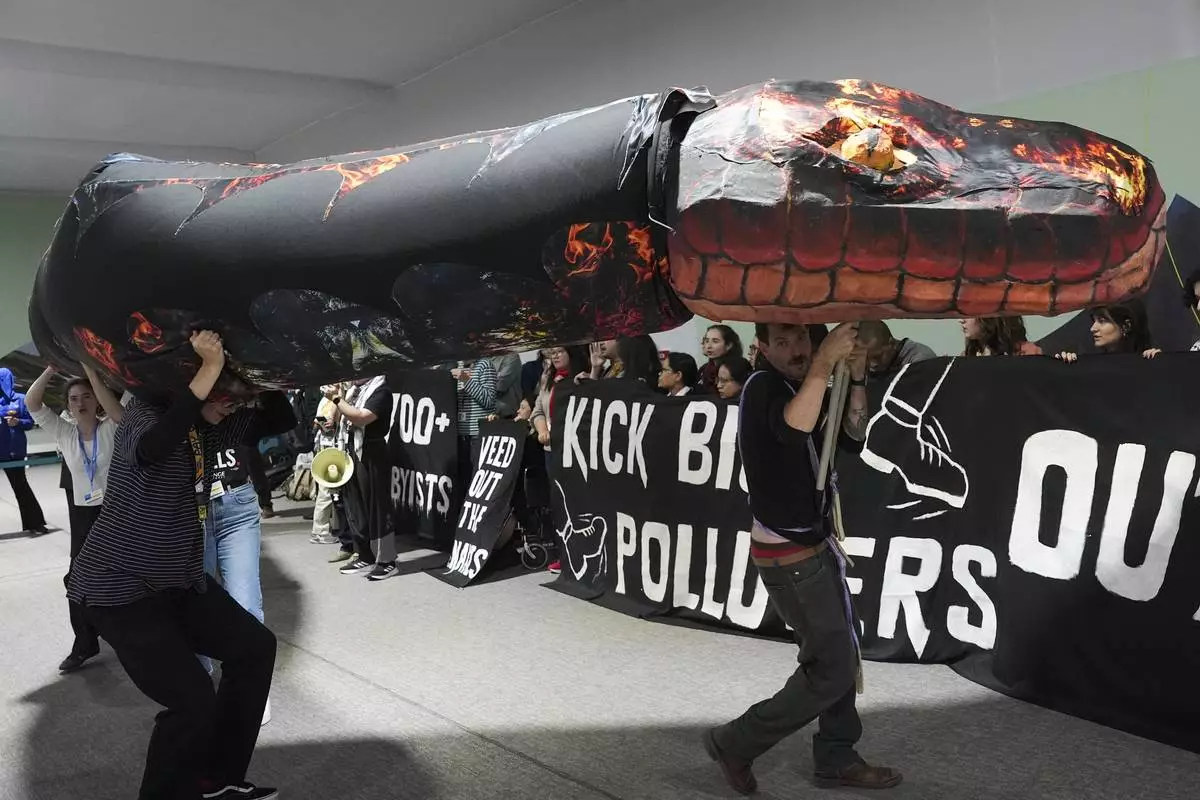

One of this year’s pieces was a larger-than-life snake for an action with the slogan “Weed Out the Snakes,” calling attention for the removal of big polluters and fossil fuel lobbyists at climate talks, something that's been “outrageous,” said Jax Bongon, whose organization is part of the Kick Big Polluters Out coalition. “Would you invite an arsonist to put out the fire?”

It's an issue that's "particularly hard for me as someone from the Philippines,” Bongon added, but called it "really uplifting" to watch the action come together despite challenges.

Demonstrators hoisted the fire-colored serpent with on their shoulders and heads. Together, their hisses filled the tent, bringing the snake to life.

“I think that the only reason people dare to do this is because, one, they're struggling on how to be heard,” said Dani Rupa, one of the artists working in Baku with The Artivist Network. “But, two, that there is like creative support for them to be able to do this.”

The Artivist Network have been doing this for a long time, attending COPs unofficially since the early 2000s and officially since they formalized in 2018. Sathananthar's seen the multitude of ways protestors have had to argue with host countries and the UNFCCC governing body to get space for activism. But this year, especially, he said it's a struggle — “negotiations within negotiations” that have had Sathananthar staying up late into the night in talks and on occasion have left him “fuming.”

A spokesperson for UNFCCC said they've “been a recognized global leader in ensuring safe civic spaces at COPs for many years" which normally doesn't happen at other intergovernmental events.

Still, activists feel that only being able to protest within certain areas throughout the venue — when previous years have seen mass street marches in host cities — can be frustrating.

“Every action you now have to fight for desperately," Sathananthar said. “We fought to get these spaces and we will fight to keep them."

Follow Melina Walling on X at @MelinaWalling. Follow Joshua A. Bickel on X and Instagram.

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.

Anna Varszegi, of Budapest, Hungary, works on preparations for a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Dani Rupa, from Budapest, Hungary, paints a snake for a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Kevin Buckland, right, and other activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels called weed out the snakes at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Activists with signs spell out "pay up" for climate finance in the Baku Olympic Stadium during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Activists with signs spell out "pay up" for climate finance in the Baku Olympic Stadium during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Sergei Grits)

Kevin Buckland, front, and other activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels called weed out the snakes at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Shaq Koyok, of Malaysia, paints a sign ahead of a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Anna Varszegi, of Budapest, Hungary, sketches out patterns during preparations for a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Dani Rupa, from Budapest, Hungary, paints a snake for a demonstration during the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Thursday, Nov. 14, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)

Activists participate in a demonstration against fossil fuels called weed out the snakes at the COP29 U.N. Climate Summit, Friday, Nov. 15, 2024, in Baku, Azerbaijan. (AP Photo/Joshua A. Bickel)