COLUMBUS, Ohio (AP) — The Ohio Supreme Court heard oral arguments Wednesday in a long-running public records case pitting the state’s top law enforcement officer against a national watchdog group that is digging into his ties with the Republican Attorneys General Association.

At issue is whether GOP Attorney General Dave Yost should be required to provide records to an appeals court that had been requested by the Center for Media and Democracy, which pertain to the nonprofit Republican association as well as its fundraising arm, the Rule of Law Defense Fund. Yost's office also is fighting a magistrate's order requiring the attorney general to be deposed in the now five-year-old case.

The center, an investigative group, is seeking records from a period when RAGA — a nonprofit that accepts corporate donations — organized a letter opposing clean air restrictions to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that was signed by Republican attorneys general. More recently, the association came under fire for soliciting thousands of supporters of Donald Trump to march on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021.

Ohio Solicitor General T. Elliot Gaiser told the court Wednesday that its decision could have ramifications for public records law in the state.

“Essentially, this is a question of if a precedent is set for a deposition of an attorney general in this case, it would be open season for lawfare and the weaponization of the public records act for witchhunts by every gadfly,” Gaiser said.

The center initially requested the documents in March 2020, including records associated with RAGA's winter meeting of that year.

Yost responded at the time that his office had no pertinent records to turn over or that the information being sought wasn’t a record. As part of a legal challenge by the center, a Tenth District Court of Appeals magistrate ordered his office to answer a series of questions about the communications and subsequently directed him to produce certain documents for private, in-camera review.

The lower court said a review of the requested materials would help it determine whether they were public records or not — dependent on factors such as whether the communications were carried out on state time, were conducted by public employees or involved Yost’s official duties.

Yost appealed the magistrate's orders to the state's high court, arguing in part that searching for the requested records would potentially reach into the communications of Republican attorneys general in other states as well as his own staff’s personal and campaign email accounts.

He has also said that the discovery could potentially sweep in irrelevant information having nothing to do with RAGA or its fundraising arm, such as communications about multistate lawsuits his office might be involved in, say, against an e-cigarette maker or Google.

Chief Justice Sharon Kennedy asked Wednesday whether the lower court’s order might be asking too much of the state — for it to produce information, as opposed to records. Justice Jennifer Brunner, the panel's lone Democrat, asked whether allowing the public official to determine on their own that records aren't public would be a slippery slope.

“Depending on how this decision comes out, if an official decided to engage in illegal or unethical behavior, he would just simply do it on a private email and the public would probably not be able to find out,” she said.

Jeffrey Vardaro, the Center for Media and Democracy's attorney, reminded the court that the outstanding order would merely allow the Tenth District magistrate — not the center or the public at large — to review certain documents. He said that undercuts the state's argument that the lawsuit is intended to harass or embarrass Yost, who he reminded has the job of enforcing Ohio's public records law.

Vardaro warned the court against making a decision that could allow a public official to unilaterally determine that "entire categories of what should be public records are not public," prevent courts from weighing in, and empower the official to “refuse to testify about what the records were even about.”

“And so it would take the Sunshine Act and turn it into a black box," he added.

FILE - Ohio attorney general Dave Yost speaks during a rally for Republican vice presidential candidate Sen. JD Vance, R-Ohio, in Middletown, Ohio, July 22, 2024. (AP Photo/Paul Vernon, File)

HOPKINSVILLE, Ky. (AP) — Torrential rains and flash flooding battered parts of the Midwest and South on Friday, killing a boy in Kentucky who was swept away as he walked to catch his school bus. Many communities were left reeling from tornadoes that destroyed entire neighborhoods and killed at least seven people earlier this week.

Round after round of heavy rains have pounded the central U.S. for days, and forecasters warned that it could persist through Saturday. Satellite imagery showed thunderstorms lined up like freight trains over communities in Arkansas, Tennessee and Kentucky, according to the national Weather Prediction Center in Maryland.

In Frankfort, Kentucky, a 9-year-old boy died in the morning after floodwaters swept him away while he was walking to a school bus stop, Gov. Andy Beshear said on social media. Officials said Gabriel Andrews' body was found about a half-mile from where he went missing.

The downtown area of Hopkinsville, Kentucky — a city of 31,000 residents 72 miles (116 kilometers) northwest of Nashville — was submerged. A dozen people were rescued from homes, and dozens of pets were moved away from rising water, a fire official said.

“The main arteries through Hopkinsville are probably 2 feet under water,” Christian County Judge-Executive Jerry Gilliam said earlier.

Tony Kirves and some friends used sandbags and a vacuum to try to hold back rising waters that covered the basement and seeped into the ground floor of his photography business in Hopkinsville. Downtown was “like a lake,” he said.

“We’re holding ground,” he said. “We’re trying to maintain and keep it out the best we can."

A corridor from northeast Texas through Arkansas and into southeast Missouri, which has a population of about 2.3 million, could see clusters of severe thunderstorms late Friday. The National Weather Service’s Oklahoma-based Storm Prediction Center warned of the potential for intense tornadoes and large hail.

The seven people killed in the initial wave of storms that spawned powerful tornadoes on Wednesday and early Thursday were in Tennessee, Missouri and Indiana.

Tennessee Gov. Bill Lee said entire neighborhoods in the hard-hit town of Selmer were “completely wiped out” and it was too early to know whether there were more deaths as searches continued.

Heavy rains were expected to continue in parts of Missouri, Kentucky and elsewhere in the coming days and could produce dangerous flash floods. The weather service said 45 river locations in multiple states were expected to reach major flood stage, with extensive flooding of structures, roads and other critical infrastructure possible.

In Christian County, which includes Hopkinsville, 6 to 10 inches (15.2 to 25.4 centimeters) fell since Wednesday evening, the National Weather Service said Friday afternoon. The rain caused the Little River to surge over its banks, and 4 to 8 inches (10.2 to 20.3) centimeters more could fall by Sunday, it said.

A pet boarding business was under water, forcing rescuers to move dozens of dogs to a local animal shelter, said Gilliam, the county executive. Crews rescued people from four or five vehicles and multiple homes, mostly by boat, said Randy Graham, the emergency management director in Christian County.

“This is the worst I’ve ever seen downtown,” Gilliam said.

Hundreds of Kentucky roads were impassable because of floodwaters, downed trees or mud and rock slides, and the number of closures were likely to increase with more rain late Friday and Saturday, Beshear said.

A landslide blocked a nearly 3-mile (4.8-kilometer) stretch of Mary Ingles Highway in the state's north, according to the Kentucky Transportation Cabinet. A landslide closed the same section of road in 2019, and it reopened last year, WLWT-TV reported.

Flash flooding is particularly worrisome in rural Kentucky where water can rush off the mountains into the hollows. Less than four years ago, dozens died in flooding in the eastern part of the state.

Extreme flooding across a corridor that includes Louisville, Kentucky, and Memphis — which have major cargo hubs — could also lead to shipping and supply chain delays, said Jonathan Porter, chief meteorologist at AccuWeather.

Forecasters attributed the violent weather to warm temperatures, an unstable atmosphere, strong wind shear and abundant moisture streaming from the Gulf. At least 318 tornado warnings have been issued by the National Weather Service since this week’s outbreak began Wednesday.

The outburst comes at a time when nearly half of National Weather Service forecast offices have 20% vacancy rates after Trump administration job cuts — twice that of just a decade ago.

Homes were ripped to their foundations this week in Selmer, which was hit by a tornado with winds estimated up to 160 mph (257 kph), according to the weather service. Advance warning of storms likely saved lives, as hundreds of people sheltered at a courthouse, the governor said.

In neighboring Arkansas, a tornado near Blytheville lofted debris at least 25,000 feet (7.6 kilometers) high, according to weather service meteorologist Chelly Amin. The state’s emergency management office reported damage in 22 counties from tornadoes, wind, hail and flash flooding.

Workers on bulldozers cleared rubble along the highway that crosses through Lake City, where a tornado with winds of 150 mph (241 kph) sheared roofs off homes, collapsed brick walls and tossed cars into trees.

Mississippi's governor said at least 60 homes were damaged. And in far western Kentucky, four people were injured while taking shelter in a vehicle under a church carport, according to the emergency management office in Ballard County.

Schreiner reported from Shelbyville, Kentucky. Associated Press writers Andrew DeMillo in Little Rock, Arkansas, Jonathan Mattise in Nashville, Tennessee, Adrian Sainz in Memphis, Tennessee, Jeff Martin in Marietta, Georgia, Obed Lamy in Hopkinsville, and John Raby in Charleston, West Virginia, contributed.

Drew's on the River Sports Bar and Grill employees, family, and friends, including Steve Schmidt, third from left, and Dave Schmidt, right, sons of owner Ron Schmidt, Remove exterior windows in the rain as the Ohio River rises behind them, Friday, April 4, 2025, in Cincinnati. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Drew's on the River Sports Bar and Grill manager, Carrie Haines, right, Frank left, and Steve Schmidt son of owner Ron Schmidt, center load furnature on to trailer in the rain as the Ohio River rises, Friday, April 4, 2025, in Cincinnati. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Stairs vanish into the rising Ohio River in front of Drew's on the River Sports Bar and Grill, Friday, April 4, 2025, in Cincinnati. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

The Green River floods in Casey County, Ky., on Friday, April 4, 2025. (Ryan C. Hermens/Lexington Herald-Leader via AP)

Floodwaters cover Kentucky Route 39 in Lincoln County, Ky., on Friday, April 4, 2025. (Ryan C. Hermens/Lexington Herald-Leader via AP)

A street is closed off due to flood waters in Hopkinsville, Ky., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Flood waters rise around homes on Bell Street in Hopkinsville, Ky., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

City of Owensboro workers put sandbags to protect the fountains in preparation for flooding of the Ohio River in Smothers Park in Owensboro, Ky., on Friday, April 4, 2025. (Alan Warren/The Messenger-Inquirer via AP)

Floodwaters cover Kentucky Route 39 in Lincoln County, Ky., on Friday, April 4, 2025. (Ryan C. Hermens/Lexington Herald-Leader via AP)

Caution tape is placed in MacGregor Park on the banks of the Cumberland River in Clarksville Tenn., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

John Milt places sandbags in preparation for flooding near the banks of the Cumberland River in Clarksville Tenn., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Caution tape is placed in MacGregor Park on the banks of the Cumberland River in Clarksville Tenn., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Workers clear landslide debris, caused by heavy rains overnight, from Mary Ingles Highway, Friday, April 4, 2025, in Newport, Ky. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Workers clear landslide debris, caused by heavy rains overnight, from Mary Ingles Highway, Friday, April 4, 2025, in Newport, Ky. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Workers clear landslide debris, caused by heavy rains overnight, from Mary Ingles Highway, Friday, April 4, 2025, in Newport, Ky. (AP Photo/Carolyn Kaster)

Flood waters cover the entryway to the Weather Stone subdivision off Russellville Road in Bowling Green, Ky., on Friday, April 4, 2025, after excessive rainfall Thursday into Friday drenched southcentral Kentucky with more than four and a half inches of rain. (Grace McDowell /Daily News via AP)

Flood waters cover the entryway to the Weather Stone subdivision off Russellville Road in Bowling Green, Ky., on Friday, April 4, 2025, after excessive rainfall Thursday into Friday drenched southcentral Kentucky with more than four and a half inches of rain. (Grace McDowell /Daily News via AP)

A car sits in a flooded ditch on the corner of Sumpter Avenue and Normal Street in Bowling Green, Ky., on Friday, April 4, 2025, after excessive rainfall Thursday into Friday drenched southcentral Kentucky with more than four and a half inches of rain. (Grace McDowell /Daily News via AP)

Vehicles travel through water covering Russellville Road in Bowling Green, Ky., on Friday, April 4, 2025, after excessive rainfall Thursday into Friday drenched southcentral Kentucky with more than four and a half inches of rain. (Grace McDowell /Daily News via AP)

Vehicles travel through water covering Russellville Road in Bowling Green, Ky., on Friday, April 4, 2025, after excessive rainfall Thursday into Friday drenched southcentral Kentucky with more than four and a half inches of rain. (Grace McDowell /Daily News via AP)

Signs at Basil Griffin Park in Bowling Green, Ky., stand in flooded waters on Friday, April 4, 2025, after excessive rainfall Thursday into Friday drenched southcentral Kentucky with more than four and a half inches of rain. (Grace McDowell /Daily News via AP)

A stranded car sits in a flooded ditch on the off-ramp of I-165 to Russellville Road in Bowling Green, Ky., on Friday, April 4, 2025, after excessive rainfall Thursday into Friday drenched southcentral Kentucky with more than four and a half inches of rain. (Grace McDowell /Daily News via AP)

Flood waters cover the driveways of a set of homes on the corner of Sumpter Avenue and Normal Street in Bowling Green, Ky., on Friday, April 4, 2025, after excessive rainfall Thursday into Friday drenched southcentral Kentucky with more than four and a half inches of rain. (Grace McDowell /Daily News via AP)

Floodwaters rise in downtown Hopkinsville, Ky., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Floodwaters rise in downtown Hopkinsville, Ky., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Josh Brashears walks though a flooded street in Hopkinsville, Ky., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Brandon Sanderson, left, Josh Brashears set up sandbags after flooding in Hopkinsville, Ky., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Cars sit in a flooded street in Hopkinsville, Ky., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

The streets are flooded in Hopkinsville, Ky., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Tony Kirves prepares for flooding inside this photography studio in Hopkinsville, Ky., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Tony Kirves prepares for flooding inside this photography studio in Hopkinsville, Ky., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Tony Kirves prepares for flooding inside this photography studio in Hopkinsville, Ky., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

A person rides a bike in a flooded street in Hopkinsville, Ky., Friday, April 4, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

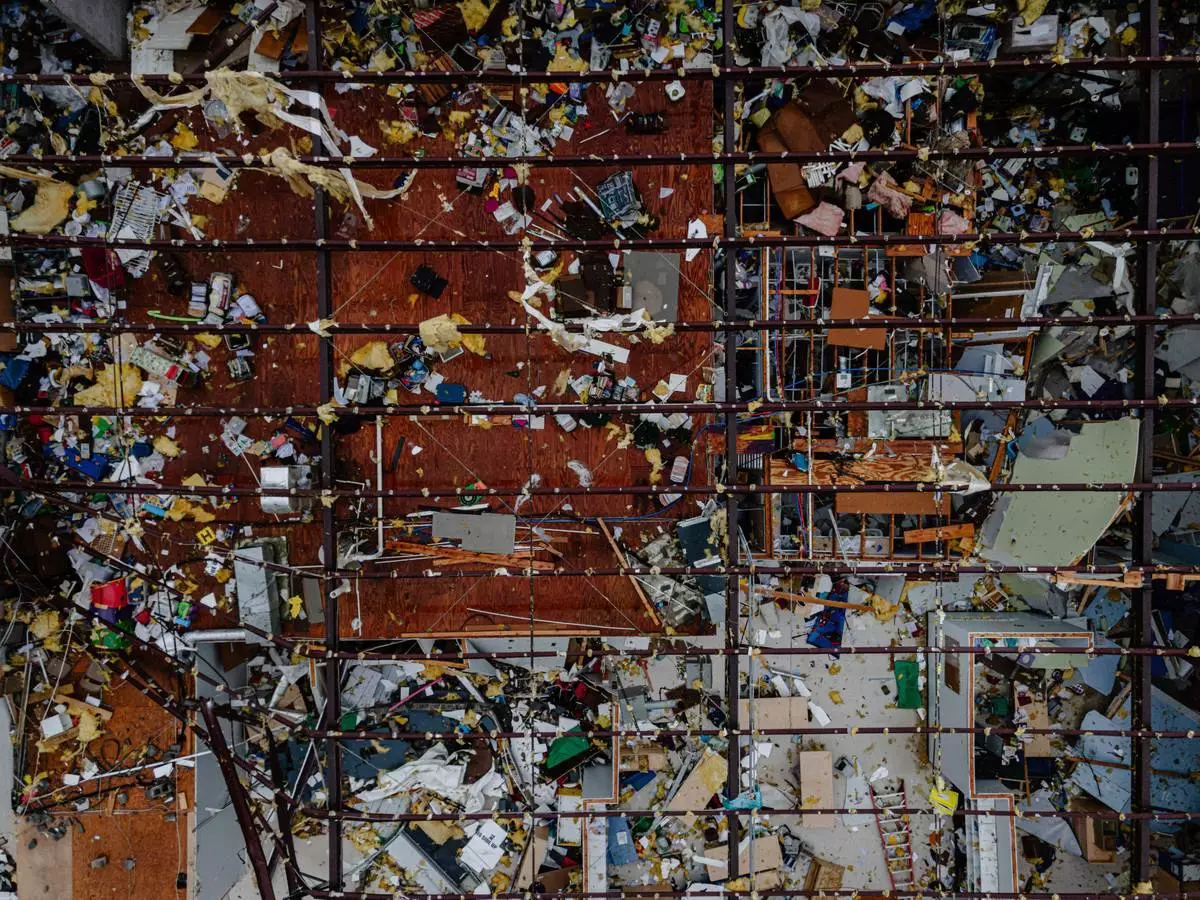

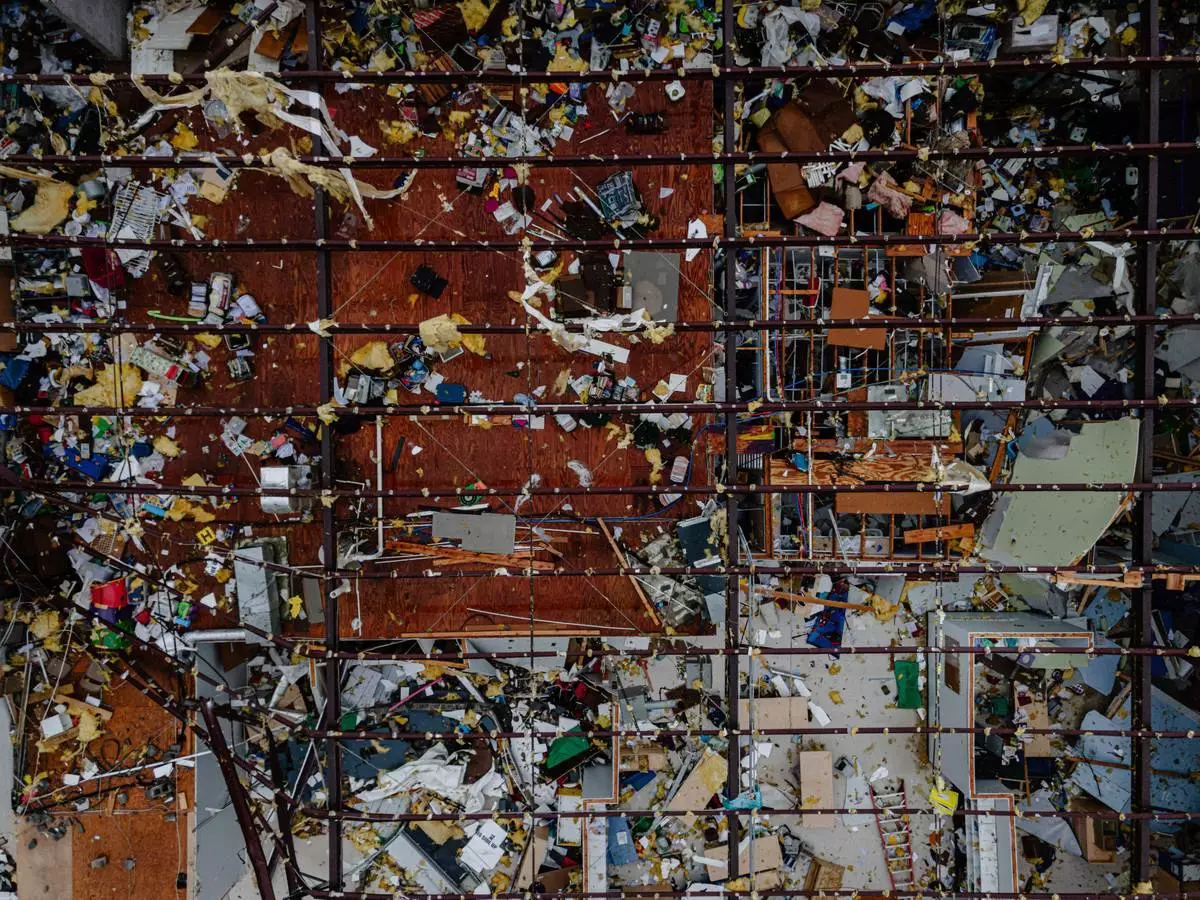

People clean up a damaged warehouse after severe weather passed the area in Carmel, Ind., Thursday, April 3, 2025. (AP Photo/Michael Conroy)

Family and friends begin picking up whats left of a house that was ripped off it's foundation and thrown over 75 feet away along Tippah County Rd. 122 in the Three Forks Community near Walnut Miss., Thursday, April 3, 2025. (Thomas Wells /The Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal via AP)

A piece of home decor rests inside a claw foot bathtub that was thrown from it's house along Tippah County Rd. 122 in the Three Forks Community near Walnut Miss., Thursday, April 3, 2025. (Thomas Wells /The Northeast Mississippi Daily Journal via AP)

People look over the debris around a home at Lake City, Ark., on Thursday, April 3, 2025. (AP Photo/Adrian Sainz)

Willy Barns gathers cloths at his house after severe weather passed the area in Selmer, Tenn., Thursday, April 3, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Jamar Atkins helps to clean up a house after severe weather passed through Selmer, Tenn., Thursday, April 3, 2025. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Dana Hardin, a 25-year former employee of Gordon-Hardy, which was destroyed, looks on near the debris of the KEP Electric building after a tornado passed through an industrial industrial park on Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Jeffersontown, Ky. (AP Photo/Jon Cherry)

Lauren Fraser picks up paperwork in the damaged second floor offices of Specialty Distributors after a tornado passed through an industrial industrial park on Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Jeffersontown, Ky. (AP Photo/Jon Cherry)

Mike Davis moves debris from a damaged business in the Triad Building, a business plaza, after severe weather passed through Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Louisville, Ky. (AP Photo/Jon Cherry)

A specialty distributors building is in ruins after severe weather passed through an industrial park on Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Jeffersontown, Ky. (AP Photo/Jon Cherry)

William Fraser takes photographs inside the warehouse of a damaged building of Specialty Distributors after severe weather passed through an industrial industrial park on Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Jeffersontown, Ky. (AP Photo/Jon Cherry)

A storm damaged home is seen Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Selmer, Tenn. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

People remove items from a business damaged in the Triad Building, a business plaza, after severe weather passed through on Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Louisville, Ky. (AP Photo/Jon Cherry)

In an aerial view, damaged structures are seen at the Triad Building, a business plaza, after severe weather passed through Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Louisville, Ky. (AP Photo/Jon Cherry)

Storm damaged homes and broken trees are seen Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Selmer, Tenn. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Rep. David Kustoff, R-Tenn., speaks about the storm damage during news conference Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Selmer, Tenn. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Debris and goods are removed from damaged businesses in the Triad Building, a business plaza, after severe weather passed through Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Louisville, Ky. (AP Photo/Jon Cherry)

People remove debris from a damaged business in the Triad Building, a business plaza, after severe weather passed through on Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Louisville, Ky. (AP Photo/Jon Cherry)

A home is in ruins after severe weather passed through Lake City, Ark., on Thursday, April 3, 2025. (AP Photo/Adrian Sainz)

A shipping and receiving bay door is damaged along with the interior of the Gordon-Hardy building after severe weather passed through an industrial industrial park on Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Jeffersontown, Ky. (AP Photo/Jon Cherry)

In an aerial view the interior of a damaged business is seen at the Triad Building, a business plaza, after severe weather passed through on Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Louisville, Ky. (AP Photo/Jon Cherry)

Daniel Fraser carries a computer in the damaged second floor offices of Specialty Distributors after a tornado passed through an industrial industrial park on Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Jeffersontown, Ky. (AP Photo/Jon Cherry)

A storm damaged home is seen Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Selmer, Tenn. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Gov. Bill Lee speaks about the storm damage during a news conference Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Selmer, Tenn. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

Storm damaged homes are seen Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Selmer, Tenn. (AP Photo/George Walker IV)

The interior of the destroyed Gordon-Hardy building after a severe weather passed through an industrial industrial park on Thursday, April 3, 2025, in Jeffersontown, Ky. (AP Photo/Jon Cherry)